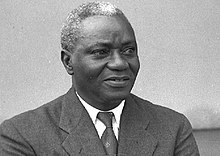

J. B. Danquah

Nana Joseph Boakye Danquah | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Joseph Kwame Kyeretwie Boakye Danquah 18 December 1895 Bepong, Gold Coast |

| Died | 4 February 1965 (aged 69) |

| Nationality | Ghanaian |

| Alma mater | University of London |

| Occupation | Lawyer, politician |

| Political party | United Gold Coast Convention |

| Spouse(s) | Elizabeth Vardon |

| Children | 4 |

| Relatives | Nana Akufo-Addo (great-nephew) |

Joseph Kwame Kyeretwie Boakye Danquah (18 December 1895 – 4 February 1965) was a Ghanaian politician, scholar, lawyer, and one of the founding fathers of Ghana. He played a significant role in pre- and post-colonial Ghana, which was formerly the Gold Coast, and is credited with giving Ghana its name.[1] During his political career, Danquah was one of the primary opposition leaders to Ghanaian president and independence leader Kwame Nkrumah. Danquah was described as the "doyen of Gold Coast politics" by the Watson Commission of Inquiry into the 1948 Accra riots.[2] J.B Danquah can be applause for his works. Being a scholar and a historian, he researched on the name which will suit the new country which is to gain independence. The name has to remind the generations to come know their origin and history of their people. [3]

Early life and education[]

Danquah was born on 18 December 1895 in the town of Bepong in Kwahu in the Eastern Region of Ghana (then the Gold Coast). He was descended from the royal family of Ofori Panin Fie, once the rulers of the Akyem states, and one of the most influential families in Ghanaian politics. His elder brother is Nana Sir Ofori Atta I and his son is actor Paul Danquah.

At the age of six, Danquah began schooling at the Basel Mission School at Kyebi. He attended the Basel Mission Senior School at Begoro. On successful completion of his standard seven examinations in 1912, he was employed by Vidal J. Buckle, a barrister-at-law in Accra, as a clerk, a job that aroused his interest in law.

After passing the Civil Service Examinations in 1914, Danquah became a clerk at the Supreme Court of the Gold Coast, which gave him the experience to be appointed by his brother, Nana Sir Ofori Atta I, who had become chief two years earlier, as secretary of the Omanhene's Tribunal in Kyebi.[2] Following the influence of his brother, Danquah was appointed as the assistant secretary of the Conference of Paramount Chiefs of the Eastern Province, which was later given statutory recognition to become the Eastern Provincial Council of Chiefs. His brilliance influenced his brother to send him to Britain in 1921 to read law.

After two unsuccessful attempts at the University of London matriculation, Danquah passed in 1922, enabling him to enter the University College of London as a philosophy student. He earned his B.A. degree in 1925, winning the John Stuart Mill Scholarship in the Philosophy of Mind and Logic. He then embarked on a Doctor of Philosophy degree, which he earned in two years with a thesis entitled "The Moral End as Moral Excellence". He became the first West African to obtain the Doctor of Philosophy degree from a British university. While he worked on his thesis, he entered the Inner Temple and was called to the Bar in 1926.

During his student days, he had two sons and two daughters by two different women, neither of whom he married. In London, Danquah took time off his studies to participate in student politics, serving as editor of the West African Students' Union (WASU) magazine and becoming the Union's president.

Career[]

Danquah went into private legal practice upon his return to Ghana in 1927. In 1929 he helped J. E. Casely Hayford found the Gold Coast Youth Conference (GCYC) and was Secretary General from 1937 to 1947.[4] In 1931, Danquah established The Times of West Africa, originally called the West Africa Times, which was the first daily newspaper in Ghana published between 1931 and 1935.[5] A column called "Women's Corner" was pseudonymously written by Mabel Dove, daughter of prominent barrister Francis Dove. She became Danquah's first wife in 1933, bearing him a son.[2] Danquah later married Elizabeth Vardon.[2][4] In 1935, he became an executive member of the International African Friends of Ethiopia, a Pan-Africanist organization based in London.

Politics[]

Danquah became a member of the Legislative Council in 1946 and actively pursued independence legislation for his country. In 1947 he helped to found the pro-independence United Gold Coast Convention (UGCC) as a combination of chiefs, academics and lawyers,[6][7] including George Alfred Grant, Robert Benjamin Blay, R. A. Awoonor-Williams, Edward Akufo-Addo, and Emmanuel Obetsebi-Lamptey. Kwame Nkrumah was invited to be the new party's general secretary. In 1948, following a boycott of European imports and subsequent rioting in Accra, Danquah was one of "the big six" (the others being Nkrumah, Akufo-Addo, Obetsebi-Lamptey, Ebenezer Ako-Adjei and William Ofori Atta) who were detained for a month by the colonial authorities.

Danquah's historical research led him to agree with Nkrumah's proposition that on independence the Gold Coast be renamed Ghana after the early African empire of that name.[8] However, Danquah and Nkrumah subsequently disagreed over the direction of the independence movement and parted ways after two years. Nkrumah went on to form the Convention People's Party (CPP) and eventually became the first president of independent Ghana.

Danquah's Role in the Founding of the University of Ghana[]

Danquah played a role in the establishment of the University of Ghana, the premier and the largest university in Ghana.[9] In the book commissioned by the University of Ghana, Professor Francis Agbodeka (1998) reports that "Two members of the Legislative Council - Dr J. B. Danquah and Prof. Christian Baeta on their own volition worked on the question of securing funds for the project. More significant, Bourret (1949), in almost a contemporaneous account, observed that the strong and united opinion expressed by Dr. Nanka-Bruce in a Radio Station Zoy address to the People of the Gold Coast in October 1947, “was largely instrumental in influencing the Secretary of State for the colonies” to finally give his consent in 1947, “for the establishment of a Gold Coast university college.”

Actually, the establishment of the University of Ghana, based on the Elliot Commission's Majority Report (championed by Sir Arku Korsah), was the culmination of immense work of several organizations, committees, institutions, and prominent individuals, at home and abroad. Among some of the most prominent Ghanaians, members of organizations and civil society groups that campaigned for the establishment of the University of College of the Gold Coast/Ghana, included also Dr. Nanka-Bruce, Rev. Prof. C. G. Baeta, and Sir E. Asafu-Adjaye, Dr. J. B. Danquah, included. The Asantehene agreed to the proposition after the Commission proposed establishment of a university in Kumasi, in the Ashanti Region. In sum, the Gold Coast citizenry, as a collective, successfully advocated for the establishment of the University Collège of the Gold Coast in association with the University of London, in 1948, after the Elliot Commission report, on which Sir Arku Korsah of the Gold Coast sat.[10] In 1961 the Government of Ghana under Kwame Nkrumah passed the University of Ghana Act, 1961 (Act 79) to replace the then University College of Ghana.

Arrest, detention and death[]

Danquah stood as a presidential candidate against Nkrumah in April 1960 but lost the election. On 3 October 1961, Danquah was arrested under the Preventive Detention Act, on the grounds of involvement with alleged plans to subvert the CPP government.[11] He was released on 22 June 1962. He was later elected president of the Ghana Bar Association.[12]

Danquah was again arrested on 8 January 1964, for allegedly being implicated in a plot against the President. He suffered a heart attack and died while in detention at Nsawam Medium Prison on 4 February 1965.[13]

After the overthrow of the CPP government in February 1966 by the National Liberation Council (NLC), Danquah was given a national funeral.

Publications[]

Among his writings are Gold Coast: Akan Laws and Customs and the Akim Abuakwa Constitution (1928), a play entitled The Third Woman (1943), and The Akan Doctrine of God (1944).[8] The latter book demonstrated the compatibility of African religion with Christianity, and is considered a "milestone"[14] for African Protestants looking for ways to reclaim their African heritage.

Legacy[]

The J. B. Danquah Memorial Lecture Series was inaugurated in 1968 in memory of Danquah, who was also a founding member of the Ghana Academy of Arts and Sciences (GAAS).[15] The Danquah Institute was set up in commemoration of his work and to promote his ideas posthumously.[16]

Danquah Circle, a roundabout at Osu in Accra, was also named after him.

References[]

- ^ "Dr. Joseph (Kwame Kyeretwie) Boakye Danquah - Researched by NiiCa". Niica. Archived from the original on 9 September 2012. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Dr. J.B. Danquah (1895–1965)". Ghana Nation. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- ^ "Big Six Enduring Lessons From The Founding Fathers Of Ghana". Retrieved 2021-08-27.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kwesi Atta Sakyi, "Tribute to J.B. Danquah", Vibe Ghana, 17 January 2013.

- ^ Danquah, Meri Nana-Ama (6 February 2015). "Ideals that last". Graphic Online. Ghana. Retrieved 6 February 2015.

- ^ Birmingham, David. Kwame Nkrumah: The Father of African Nationalism (revised edition), Ohio University Press, 1998, p. 13.

- ^ Timothy Ngnenbe (4 August 2020). "Ghana pays tribute to founders'". Graphic Online. Retrieved 5 August 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Joseph B. Danquah", Encyclopaedia of World Biography.

- ^ Edmund Smith-Asante (27 February 2015). "Name University of Ghana after Dankwa — Prof. Ewusi". Graphic Online. p. 19. Retrieved 27 February 2015.

- ^ "A History of University of Ghana. Half a Century of Higher Education (1948–1998)", University of Ghana.

- ^ "Dr. J. B. Danquah Profile:", GhanaWeb.

- ^ "J.B. Danquah", Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ Cameron Duodu, "Dr J B Danquah's death is sticking in the throats of some people like a dead rat", Daily Guide, 21 February 2015.

- ^ Kevin Ward, "Africa", in Adrian Hastings (ed.), A World History of Christianity, Cassell/Eerdmans, 1999, p. 232.

- ^ "J.B. Danquah Memorial Lectures". GAAS. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- ^ "Commemoration of the 50th Anniversary of the Death of Dr. J. B. Danquah". Danquah Institute. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- 1895 births

- 1965 deaths

- Akan people

- Ghanaian MPs 1951–1954

- Alumni of the University of London

- Ghanaian Christians

- Ghanaian Freemasons

- United Gold Coast Convention politicians

- Ghanaian historians

- Candidates for President of Ghana

- Ghanaian pan-Africanists

- Ghanaian lawyers

- Members of the Inner Temple

- Ofori-Atta family

- 20th-century historians

- 20th-century lawyers

- Ghanaian independence activists

- Fellows of the Ghana Academy of Arts and Sciences