Jain art

| Part of a series on |

| Jainism |

|---|

|

|

|

Jain art refers to religious works of art associated with Jainism. Even though Jainism spread only in some parts of India, it has made a significant contribution to Indian art and architecture.[1]

In general Jain art broadly follows the contemporary style of Indian Buddhist and Hindu art, though the iconography, and the functional layout of temple buildings, reflects specific Jain needs. The artists and craftsmen producing most Jain art were probably not themselves Jain, but from local workshops patronized by all religions. This may not have been the case for illustrated manuscripts, where many of the oldest Indian survivals are Jain.

Jains mainly depict tirthankara or other important people in a seated or standing meditative posture, sometimes on a very large scale. Yaksa and yaksini, attendant spirits who guard the tirthankara, are usually shown with them.[2]

Iconography of tirthankaras[]

A tirthankara or Jina is represented either seated in lotus position (Padmasana) or standing in the meditation Khadgasana (Kayotsarga) posture.[3][4] This latter, which is similar to the military standing at attention is a difficult posture to hold for a long period, and has the attraction to Jains that it reduces to the minimum the amount of the body in contact with the earth, and so posing a risk to the sentient creatures living in or on it. If seated, they are usually depicted seated with their legs crossed in front, the toes of one foot resting close upon the knee of the other, and the right hand lying over the left in the lap.[5]

Tirthanakar images do not have distinctive facial features, clothing or (mostly) hair-styles, and are differentiated on the basis of the symbol or emblem (Lanchhana) belonging to each tirthanakar except Parshvanatha. Statues of Parshvanath have a snake crown on the head. The first Tirthankara Rishabha can be identified by the locks of hair falling on his shoulders. Sometimes Suparshvanath is shown with a small snake-hood. The symbols are marked in the centre or in the corner of the pedestal of the statue. The sects of Jainism Digambara and Svetambara have different depictions of idols. Digambara images are naked without any ornamentation, whereas Svetambara ones may be clothed and in worship may be decorated with temporary ornaments.[6] The images are often marked with Srivatsa on the chest and Tilaka on the forehead.[7] Srivatsa is one of the ashtamangala (auspicious symbols). It can look somewhat like a fleur-de-lis, an endless knot, a flower or diamond-shaped symbol.[8]

The bodies of tirthanakar statues are exceptionally consistent throughout the over 2,000 years of the historical record. The bodies are rather slight, with very wide shoulders and a narrow waist. Even more than is usual in Indian sculpture, the depiction takes relatively little interest in the accurate depiction of the underlying musculature and bones, but is interested in the modelling of the outer surfaces as broad swelling forms. The ears are extremely elongated, suggesting the heavy earrings the figures wore in their early lives before they took the path to enlightenment, when most were wealthy if not royal.

Sculptures with four tirthanakars, or their heads, facing in four directions, are not uncommon in early sculpture, but unlike the comparable Hindu images, these represent four different tirthanakars, not four aspects of the same deity. Multiple extra arms are avoided in tirthanakar images, though their attendants or guardians may have them.[9]

Architecture[]

Like Buddhists, Jains participated in Indian rock-cut architecture from a very early date. Remnants of ancient jaina temples and monasteries temples can be found all around India, and much early Jain sculpture is reliefs in these. Ellora Caves in Maharashtra, and the Jain temples at Dilwara near Mount Abu, Rajasthan. The Jain tower in Chittor, Rajasthan is a good example of Jain architecture.[10]

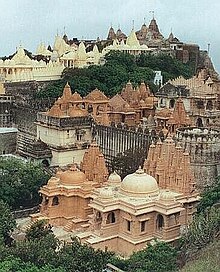

Modern and medieval Jains built many Jain temples, especially in western India. In particular the complex of five Dilwara Temples of the 11th to 13th centuries at Mount Abu in Rajasthan is a much-visited attraction. The Jain pilgrimage in Shatrunjay hills near Patilana, Gujarat is called "The city of Temples". Both of these complexes use the style of Solanki or Māru-Gurjara architecture, which developed in west India in the 10th century in both Hindu and Jain temples, but became especially popular with Jain patrons, who kept it in use and spread it to some other parts of India. It continues to be used in Jain temples, now across the world, and has recently revived in popularity for Hindu temples.

A Jain temple or Derasar is the place of worship for Jains, the followers of Jainism.[11] Jain architecture is essentially restricted to temples and monasteries, and secular Jain buildings generally reflect the prevailing style of the place and time they were built. Derasar is a word used for a Jain temple in Gujarat and southern Rajasthan. Basadi is a Jain shrine or temple in Karnataka.[12] The word is generally used in South India. Its historical use in North India is preserved in the names of the Vimala Vasahi and Luna Vasahi temples of Mount Abu. The Sanskrit word is vasati, it implies an institution including residences of scholars attached to the shrine.[13]

Temples may be divided into Shikar-bandhi Jain temples, public dedicated temple buildings, normally with a high superstructure, typically a north Indian shikhara tower above the shrine) and the Ghar Jain temple, a private Jain house shrine. A Jain temple which is known as a pilgrimage centre is often termed a Tirtha.

The main image of a Jain temple is known as a mula nayak[14] A Manastambha (column of honor) is a pillar that is often constructed in front of Jain temples. It has four 'Moortis' i.e. stone figures of the main god of that temple. One facing each direction: North, East, South and West.[15]

History[]

Earliest depictions of Jain deities (3rd-2nd centuries BCE)[]

Figures on various seals from the Indus Valley Civilisation bear similarity to jaina images, nude and in a meditative posture.[2] The Lohanipur torso is the earliest known jaina image (presumed to be Jain because of the nudity and posture), and is now in the Patna Museum. It is also one of the earliest Indian monumental sculptures in stone of a human, if the dating to the 3rd century BCE is correct;[2] it might be from about the 2nd century CE. Bronze images of the 23rd tirthankara, Pārśva, can be seen in the Prince of Wales Museum, Mumbai, and in the Patna Museum; these are dated to the 2nd century BCE. The carved Kankali Tila architrave with centaurs worshipping a Jain Stupa, is Mathura art, of circa 100 BCE, showing Hellenistic influence.[16]

The early Udayagiri and Khandagiri Caves, are a number of finely and ornately carved caves built during 2nd-century BCE excavated by King Kharavela of Mahameghavahana dynasty.[17][18]

Early reliefs (1st century BCE)[]

Chitharal Jain Monuments is the earliest Jain monument in the southernmost part of India dating back to first century BC.[19] The Chausa hoard is the oldest of group of bronzes to be found in India. The bronzes have varied dates, from between the Shunga and the Gupta periods, from (possibly) the 2nd century BC,[20] to the 6th Century AD.

Jain art at Mathura under the Guptas[]

A sandalwood sculpture of Mahāvīra was carved during his lifetime, according to tradition. Later the practice of making images of wood was abandoned, other materials being substituted.[2] The Chausa hoard, Akota Bronzes, Vasantgarh hoard are excavated groups of bronze Jain figures.

Jain art between 5th-9th century[]

The Badami cave temples and the constructed Aihole Jain monuments were built by Chalukya rulers in the 7th century,[21] and the Jain parts of the Ellora Caves date from around this period. The earliest of the large group of Jain temples at Deogarh were begun, and in general the excavation of new rock-cut sites ceased in this period, as it also did in the other two main religions. Instead stone-built temples were erected.

Jain caves, Ellora were built around the 8th century.

Medieval period (8th-16th century)[]

The Gommateshwara statue is dedicated to the Jain figure Bahubali. It was built around 983 A.D. and is one of the largest free standing statues in the world.[22]

Decorated manuscripts are preserved in jaina libraries, containing diagrams from jaina cosmology.[2] Most of the paintings and illustrations depict historical events, known as Panch Kalyanaka, from the life of the tirthankara.[23] Hansi hoard is the bronze hoard dating back to 8th-9th century.[24]

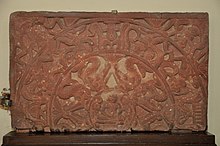

Ayagapata[]

Ayagapata is a type of votive slab associated with worship in Jainism. Numerous such stone tablets discovered during excavations at ancient Jain sites like Kankali Tila near Mathura in India. Some of them date back to 1st century C.E. These slabs are decorated with objects and designs central to Jain worship such as the stupa, dharmacakra and triratna.[25]

A large number of ayagapata (tablet of homage), votive tablets for offerings and the worship of tirthankara, were found at Mathura.[26]

Sculpture[]

Sculpture seems to have been part of Jain tradition since the last centuries BCE, but probably was mostly in wood, which has not survived. The earliert known examples of Jain sculpture are stone architraves of the 1st century BCE, found in the Art of Mathura, particularly from the Jain mound of Kankali Tila.[27]

Perhaps the most famous single Jain work of art is the Gommateshvara statue, a monolithic, 18 m statue of Bahubali, built by the Ganga minister and commander Chavundaraya around 983. It is situated on a hilltop in Shravanabelagola in the Hassan district of Karnataka state. This statue was voted as the first of the Seven Wonders of India.[28]

Smaller bronze images were probably for shrines in homes. A number of medieval collections of these have been excavated, probably deposited when populations fled from wars. These include the Vasantgarh hoard (1956, 240 pieces), Akota Bronzes (1951, 68 pieces, to 12th century), Hansi hoard (1982, 58 pieces, to 9th century), and the Chausa hoard (18 pieces, to 6th century).

Each of the twenty-four tirthankara is associated with distinctive emblems, which are listed in such texts as Tiloyapannati, Kahavaali and Pravacanasaarodhara.[2]

The Jivantasvami images represent Lord Mahavira (and in some cases other Tirthankaras) as a prince, with a crown and ornaments. The Jina is represented as standing in the kayotsarga pose.[2][29]

Lohanipur torso in Patna Museum dating back to 3rd century BCE

Chaumukha idol, LACMA, 6th Century

Rishabhanatha, Mathura Museum, 6th century

Parshvanatha, Central India, 10th or 11th century

Bahubali in Kayotsarga position, Metropolitan Museum of Art (6th CE)

Jain tirthankara in Lotus position, Cleveland Museum of Art, 10th century

Monolithic statues[]

A monolithic manastambha is a standard feature in the Jain temples of Mudabidri. They include a statue of Brahmadeva on the top as a guardian yaksha.[30]

The 58-feet tall monolithic Jain statue of Bahubali is located on Vindhyagiri Hill, Shravanabelagola built in 983 A.D.[31] was the largest free standing monolithic statue until 2016, 108 feet monolithic idol Statue of Ahimsa(statue of first Jain tirthankar, Rishabhanatha) was erected at Mangi-tungi.[32]

Gommateshwara statue, 18 metres (59 ft), built in 983 CE

Statue of Ahimsa, 33 metres (108 ft), built in 2016 CE

Bawangaja, 26 metres (85 ft), built in 15th century

The 17.8 metres (58 ft) colossal at Gopachal Hill built in 11th century

The 45 feet (14 m) tall rock cut idol at Chanderi built in 13th century

Paintings[]

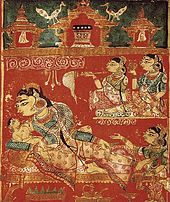

Jain temples and monasteries had mural paintings from at least 2,000 years ago, though pre-medieval survivals are rare. In addition, many Jain manuscripts were illustrated with paintings, sometimes lavishly so. In both these cases, Jain art parallels Hindu art, but the Jain examples are more numerous among the earliest survivals. The manuscripts begin around the 11th century, but are mostly from the 13th onwards, and were made in the Gujarat region. By the 15th-century they were becoming increasingly lavish, with much use of gold.[33]

The manuscript text most frequently illustrated is the Kalpa Sūtra, containing the biographies of the Tirthankaras, notably Parshvanatha and Mahavira. The illustrations are square-ish panels set in the text, with "wiry drawing" and "brilliant, even jewel-like colour". The figures are always seen in three-quarters view, with distinctive "long pointed noses and protruding eyes". There is a convention whereby the more distant side of the face protrudes, so that both eyes are seen.[34]

Rishabha, the first tirthankara, is usually depicted in either the lotus position or kayotsarga, the standing position. He is distinguished from other tirthankara by the long locks of hair falling to his shoulders. Bull images also appear in his sculptures.[35] In paintings, incidents of his life, like his marriage and Indra's marking his forehead, are depicted. Other paintings show him presenting a pottery bowl to his followers; he is also seen painting a house, weaving, and being visited by his mother Marudevi.[23]

Samavasarana[]

Depiction of Samavasarana, the divine preaching hall of the tirthankara, is a popular subject in Jain art.[36] Samavasarana is depicted as circular in shape with the tirthankara sitting on a throne without touching it (about two inches above it).[37] Around the tirthankara sit the ganadharas (chief disciples) and every living beings sit in the various halls.[38]

It can be shown in paintings, and elaborate models are also made, some occupying a whole room.

Symbols[]

The swastika is an important Jain symbol. Its four arms symbolise the four realms of existence in which rebirth occurs according to Jainism: humans, heavenly beings, hellish beings and non-humans (plants and animals).[39][40] This is conceptually similar to the six realms of rebirth represented by bhavachakra in Buddhism.[39] It is usually shown with three dots on the top, which represent the three jewels mentioned in ancient texts such as Tattvartha sūtra and Uttaradhyayana sūtra: correct faith, correct understanding and correct conduct. These jewels are the means believed in Jainism to lead one to the state of spiritual perfection, a state that is symbolically represented by a crescent and one dot on top representing the liberated soul.[41]

The hand with a wheel on the palm symbolizes ahimsā in Jainism with ahiṃsā written in the middle. The wheel represents the dharmachakra (Wheel of the Dharma), which stands for the resolve to halt the saṃsāra (wandering) through the relentless pursuit of ahimsā (compassion). In Jainism, Om is considered a condensed form of reference to the Pañca-Parameṣṭhi, by their initials A+A+A+U+M (o3m). According to the Dravyasamgraha by Acharya Nemicandra, AAAUM (or just Om) is a one syllable short form of the initials of the five parameshthis: "Arihant, Ashiri, Acharya, Upajjhaya, Muni".[42][43] The Om symbol is also used in ancient Jain scriptures to represent the five lines of the Ṇamōkāra Mantra.[44][45]

In 1974, on the 2500th anniversary of the nirvana of Mahāvīra, the Jain community chose one image as an emblem to be the main identifying symbol for Jainism.[46] The overall shape depicts the three loka (realms of rebirth) of Jain cosmology i.e., heaven, human world and hell. The semi-circular topmost portion symbolizes Siddhashila, which is a zone beyond the three realms. The Jain swastika is present in the top portion, and the symbol of Ahiṃsā in the lower portion. At the bottom of the emblem is the Jain mantra, Parasparopagraho Jīvānām. According to Vilas Sangave, the mantra means "all life is bound together by mutual support and interdependence".[47] According to Anne Vallely, this mantra is from sūtra 5.21 of Umaswati's Tattvarthasūtra, and it means "souls render service to one another".[48]

The five colours of the Jain flag represent the Pañca-Parameṣṭhi and the five vows, small as well as great:[49] The Ashtamangala are a set of eight auspicious symbols, which are different in the Digambara and Śvētāmbar traditions.[50] In the Digambara tradition, the eight auspicious symbols are Chatra, Dhvaja, Kalasha, Fly-whisk, Mirror, Chair, Hand fan and Vessel. In the Śvētāmbar tradition, these are Swastika, Srivatsa, Nandavarta, Vardhmanaka (food vessel), Bhadrasana (seat), Kalasha (pot), Darpan (mirror) and pair of fish.[50]

See also[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Jain art. |

Notes[]

- ^ Kumar 2001, p. 1.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g Shah 1995, p. 15.

- ^ Zimmer 1953, p. 209-210.

- ^ Umakant P. Shah 1987, p. 79.

- ^ Britannica Tirthankar Definition, Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ Cort 2010.

- ^ "Red sandstone figure of a tirthankara".

- ^ Jain & Fischer 1978, pp. 15–31.

- ^ Doris 1997, pp. 329–330.

- ^ Ghurye 2005, p. 62.

- ^ Babb, Lawrence A (1996). Absent lord: ascetics and kings in a Jain ritual culture. Published University of California Press. p. 66.

- ^ "Basadi".

- ^ "Architecture of the Indian Subcontinent – Glossary".

- ^ Shah 1987, p. 149.

- ^ http://www.pluralism.org/religion/jainism/introduction/tirthankaras

- ^ Jump up to: a b Quintanilla 2007, p. 22.

- ^ Krishan & Tadikonda 1996, p. 23.

- ^ Bhargava 2006, p. 357.

- ^ ASI & Monuments in Tamil Nadu.

- ^ Pal, 151

- ^ Owen 2012, p. 6.

- ^ Zimmer 1953, p. 212.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Jain & Fischer 1978, p. 16.

- ^ Arora 2007, p. 403.

- ^ "Ayagapata". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 18 April 2012.

- ^ Jain & Fischer 1978, pp. 9–10.

- ^ Cort 2010, pp. 25–26.

- ^ "And India's 7 wonders are". The Times of India. 5 August 2007.

- ^ Shah 1987, p. 35.

- ^ Setter & Asiae 1971, pp. 17–38.

- ^ The Hindu & Śravaṇa Beḷgoḷa.

- ^ NDTV & 108-Ft Tall Jain Teerthankar.

- ^ Rowland 1967, pp. 341–343.

- ^ Rowland 1967, p. 343.

- ^ Shah 1995, p. 23.

- ^ Wiley 2009, p. 184.

- ^ Shah 1987, p. 23.

- ^ Shah 1987, p. 11.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Cort 2001a, p. 17.

- ^ Jansma & Jain 2006, p. 123.

- ^ Cort 2001a, pp. 17–18.

- ^ "Om – significance in Jainism, Languages and Scripts of India, Colorado State University", cs.colostate.edu

- ^ von Glasenapp 1925, pp. 410–411.

- ^ Agarwal 2012, p. 135.

- ^ Agarwal 2013, p. 80.

- ^ Robinson 2006, p. 225.

- ^ Sangave 2001, p. 123.

- ^ Vallely 2013, p. 358.

- ^ Vijay K. Jain 2012, p. iv.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Titze 1998, p. 234.

References[]

- Guy, John (January 2012), Jain Manuscript Painting, Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Harle, J.C. (1994), The Art and Architecture of the Indian Subcontinent (2 ed.), Yale University Press, ISBN 0300062176 Alt URL

- Kumar, Sehdev (2001), Jain Temples of Rajasthan, Abhinav Publications, ISBN 978-81-7017-348-9

- Pereira, Jose (1977), Monolithic Jinas, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-2397-6

- Quintanilla, Sonya Rhie (2000), "Āyāgapaṭas: Characteristics, Symbolism, and Chronology", Artibus Asiae, 60 (1): 79–137, doi:10.2307/324994, JSTOR 3249941

- Settar, S. (1971), "The Brahmadeva Pillars. An Inquiry into the Origin and Nature of the Brahmadeva Worship among the Digambara Jains", Artibus Asiae, 33 (1/2): 17–38, doi:10.2307/3249787, JSTOR 3249787

- Rowland, Benjamin (1967), The Art and Architecture of India: Buddhist, Hindu, Jain (3 ed.), Pelican History of Art, Penguin, ISBN 0140561021

- Ghurye, G. S. (2005), Rajput Architecture, Popular Prakashan, ISBN 9788171544462

- Quintanilla, Sonya Rhie (2007), History of Early Stone Sculpture at Mathura: Ca. 150 BCE - 100 CE, BRILL, pp. Fig. 21 and 22, ISBN 9789004155374

- Cort, John E. (2010), Framing the Jina: Narratives of Icons and Idols in Jain History, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-538502-1

- Bhargava, Gopal K. (2006). Land and People of Indian States and Union Territories: In 36 Volumes. Orissa, Volume 21. Gyan Publishing House. ISBN 9788178353777.

- Krishan, Yuvraj; Tadikonda, Kalpana K. (1996), The Buddha Image: Its Origin and Development, Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, ISBN 9788121505659

- Arora, Udai Prakash (2007), Udayana, Anamika Pub & Distributors, ISBN 9788179751688

- Zimmer, Heinrich (1953) [April 1952], Campbell, Joseph (ed.), Philosophies Of India, London, E.C. 4: Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd, ISBN 978-81-208-0739-6CS1 maint: location (link)

- Owen, Lisa (2012), Carving Devotion in the Jain Caves at Ellora, BRILL Academic, ISBN 978-90-04-20630-4

- Shah, Umakant Premanand (1995), Studies in Jaina Art and Iconography and Allied Subjects in Honour of Dr. U.P. Shah, Abhinav Publications, ISBN 9788170173168

- Shah, Umakant Premanand (1987), Jaina-rūpa-maṇḍana: Jaina iconography, Abhinav Publications, ISBN 978-81-7017-208-6

- Jain, Jyotindra; Fischer, Eberhard (1978), Jaina Iconography, 12, BRILL, ISBN 9789004052598

- Srinivasan, Doris (1997), Many Heads, Arms, and Eyes: Origin, Meaning, and Form of Multiplicity in Indian Art, BRILL, ISBN 9789004107588

- Wiley, Kristi L. (2009), The a to Z of Jainism, Scarecrow Press, ISBN 9780810868212

- "Bagawati Temple (Chitral)". Thrissur Circle, Archaeological Survey of India. Archived from the original on 19 March 2016. Retrieved 23 March 2017.

- "108-Ft Tall Jain Teerthankar Idol Enters 'Guinness Records'". NDTV. 6 March 2016.

- "Delegates enjoy a slice of history at Śravaṇa Beḷgoḷa". The Hindu. Chennai. Staff Correspondent. 1 January 2006.

- Jain art