Japan during World War II

This article's lead section may be too short to adequately summarize the key points. (March 2018) |

The examples and perspective in this article deal primarily with the United States and do not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (August 2021) |

Before Pearl Harbor the Japanese had already begun imperial expansion in Manchuria, (1931) Inner Mongolia, (1936) Jehol, (1933) China, (1937) and in other territories and islands during World War 1. The Empire of Japan entered World War II on 27th, September, 1940 by signing the Tripartite Pact with Germany and Italy, and the Japanese invasion of French Indochina, though it wasn't until the attack on Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941 that the U.S. entered the conflict. Over the course of seven hours there were coordinated Japanese attacks on the U.S. -held Philippines, Guam and Wake Island, the Dutch Empire in the Dutch East Indies, Thailand and on the British Empire in Borneo, Malaya and Hong Kong.[1][2] The strategic goals of the offensive were to cripple the U.S. Pacific fleet, capture oil fields in the Dutch East Indies, and maintain their sphere of influence of China, East Asia, and also Korea. It was also to expand the outer reaches of the Japanese Empire to create a formidable defensive perimeter around newly acquired territory.[3]

Preparations for war[]

The decision by Japan to attack the United States remains controversial. Study groups in Japan had predicted ultimate disaster in a war between Japan and the U.S., and the Japanese economy was already straining to keep up with the demands of the war with China. However, the U.S. had placed an oil embargo on Japan and Japan felt that the United States' demands of unconditional withdrawal from China and non-aggression pacts with other Pacific powers were unacceptable.[4] Facing an oil embargo by the United States as well as dwindling domestic reserves, the Japanese government decided to execute a plan developed by the military branch largely led by Osami Nagano and Isoroku Yamamoto to bomb the United States naval base in Hawaii, thereby bringing the United States to World War II on the side of the Allies. On September 4, 1941, the Japanese Cabinet met to consider the war plans prepared by Imperial General Headquarters, and decided:

Our Empire, for the purpose of self-defense and self-preservation, will complete preparations for war ... [and is] ... resolved to go to war with the United States, Great Britain, and the Netherlands if necessary. Our Empire will concurrently take all possible diplomatic measures vis-a-vis the United States and Great Britain, and thereby endeavor to obtain our objectives ... In the event that there is no prospect of our demands being met by the first ten days of October through the diplomatic negotiations mentioned above, we will immediately decide to commence hostilities against the United States, Britain and the Netherlands.

The Vice Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, the chief architect of the attack on Pearl Harbor, had strong misgivings about war with the United States. Yamamoto had spent time in the United States during his youth when he studied as a language student at Harvard University (1919–1921) and later served as assistant naval attaché in Washington, D.C. Understanding the inherent dangers of war with the United States, Yamamoto warned his fellow countrymen: "We can run wild for six months or maybe a year, but after that, I have utterly no confidence."[5]

Japanese offensives (1941–1942)[]

The Imperial Japanese Navy made its surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, Oahu, Hawaii Territory, on Sunday morning, December 7, 1941. The Pacific Fleet of the United States Navy and its defending Army Air Forces and Marine air forces sustained significant losses. The primary objective of the attack was to incapacitate the United States long enough for Japan to establish its long-planned Southeast Asian empire and defensible buffer zones. However, as Admiral Yamamoto feared, the attack produced little lasting damage to the US Navy with priority targets like the Pacific Fleet's three aircraft carriers out at sea and vital shore facilities, whose destruction could have crippled the fleet on their own, were ignored. Of more serious consequences, the U.S. public saw the attack as a barbaric and treacherous act and rallied against the Empire of Japan. The United States entered the European Theatre and Pacific Theater in full force. Four days later, Adolf Hitler of Germany, and Benito Mussolini of Italy declared war on the United States, merging the separate conflicts. Following the attack on Pearl Harbor, the Japanese launched offensives against Allied forces in East and Southeast Asia, with simultaneous attacks on British Hong Kong, Thailand, British Malaya, Dutch East Indies, Guam, Wake Island, Gilbert Islands, Borneo and the Philippines.

By 1942, the Japanese Empire had launched offensives in New Guinea, Singapore, Burma, Yunnan and India, the Solomons, Timor, Aleutian Islands, Christmas Island and the Andaman Islands.

By the time World War II was in full swing, Japan had the most interest in using biological warfare. Japan's Air Force dropped massive amounts of ceramic bombs filled with bubonic plague-infested fleas in Ningbo, China. These attacks would eventually lead to thousands of deaths years after the war would end.[6] In Japan's relentless and indiscriminate research methods on biological warfare, they poisoned more than 1,000 Chinese village wells to study cholera and typhus outbreaks. These diseases are caused by bacteria that with today's technology could potentially be weaponized.[7]

South-East Asia[]

The South-East Asian campaign was preceded by years of propaganda and espionage activities carried out in the region by the Japanese Empire. The Japanese espoused their vision of a Greater Asian Co-Prosperity Sphere, and an Asia for Asians to the people of Southeast Asia, who had lived under European rule for generations. As a result, many inhabitants in some of the colonies (particularly Indonesia) actually sided with the Japanese invaders for anti-colonial reasons. However, the ethnic Chinese, who had witnessed the effects of Japanese occupation in their homeland, did not side with the Japanese.

Hong Kong surrendered to the Japanese on December 25. In Malaya the Japanese overwhelmed an Allied army composed of British, Indian, Australian and Malay forces. The Japanese were quickly able to advance down the Malayan Peninsula, forcing the Allied forces to retreat towards Singapore. The Allies lacked air cover and tanks; the Japanese had air supremacy. The sinking of HMS Prince of Wales and HMS Repulse on December 10, 1941, led to the east coast of Malaya being exposed to Japanese landings and the elimination of British naval power in the area. By the end of January 1942, the last Allied forces crossed the strait of Johore and into Singapore. In the Philippines, the Japanese pushed the combined Filipino-American force towards the Bataan Peninsula and later the island of Corregidor. By January 1942, General Douglas MacArthur and President Manuel L. Quezon were forced to flee in the face of Japanese advance. This marked one of the worst defeats suffered by the Americans, leaving over 70,000 American and Filipino prisoners of war in the custody of the Japanese.

On February 15, 1942, Singapore, due to the overwhelming superiority of Japanese forces and encirclement tactics, fell to the Japanese, causing the largest surrender of British-led military personnel in history. An estimated 80,000 Indian, Australian and British troops were taken as prisoners of war, joining 50,000 taken in the Japanese invasion of Malaya (modern day Malaysia). Many were later used as forced labour constructing the Burma Railway, the site of the infamous Bridge on the River Kwai. Immediately following their invasion of British Malaya, the Japanese military carried out a purge of the Chinese population in Malaya and Singapore.

The Japanese then seized the key oil production zones of Borneo, Central Java, Malang, Cepu, Sumatra, and Dutch New Guinea of the late Dutch East Indies, defeating the Dutch forces.[8] However, Allied sabotage had made it difficult for the Japanese to restore oil production to its pre-war peak.[9] The Japanese then consolidated their lines of supply through capturing key islands of the Pacific, including Guadalcanal.

Tide turns (1942–1945)[]

Japanese military strategists were keenly aware of the unfavorable discrepancy between the industrial potential of the Japanese Empire and that of the United States. Because of this they reasoned that Japanese success hinged on their ability to extend the strategic advantage gained at Pearl Harbor with additional rapid strategic victories. The Japanese Command reasoned that only decisive destruction of the United States' Pacific Fleet and conquest of its remote outposts would ensure that the Japanese Empire would not be overwhelmed by America's industrial might. In April 1942, Japan was bombed for the first time in the Doolittle Raid. In May 1942, failure to decisively defeat the Allies at the Battle of the Coral Sea, in spite of Japanese numerical superiority, equated to a strategic defeat for Imperial Japan. This setback was followed in June 1942 by the catastrophic loss of four fleet carriers at the Battle of Midway, the first decisive defeat for the Imperial Japanese Navy. It proved to be the turning point of the war as the Navy lost its offensive strategic capability and never managed to reconstruct the "'critical mass' of both large numbers of carriers and well-trained air groups".[10]

Australian land forces defeated Japanese Marines in New Guinea at the Battle of Milne Bay in September 1942, which was the first land defeat suffered by the Japanese in the Pacific. Further victories by the Allies at Guadalcanal in September 1942, and New Guinea in 1943 put the Empire of Japan on the defensive for the remainder of the war, with Guadalcanal in particular sapping their already-limited oil supplies.[9] During 1943 and 1944, Allied forces, backed by the industrial might and vast raw material resources of the United States, advanced steadily towards Japan. The Sixth United States Army, led by General MacArthur, landed on Leyte on October 20, 1944. In the subsequent months, during the Philippines Campaign (1944–45), the combined United States forces, together with the native guerrilla units, liberated the Philippines. By 1944, the Allies had seized or bypassed and neutralized many of Japan's strategic bases through amphibious landings and bombardment. This, coupled with the losses inflicted by Allied submarines on Japanese shipping routes began to strangle Japan's economy and undermine its ability to supply its army. By early 1945, the U.S. Marines had wrested control of the Ogasawara Islands in several hard-fought battles such as the Battle of Iwo Jima, marking the beginning of the fall of the islands of Japan.

Air raids on Japan[]

After securing airfields in Saipan and Guam in the summer of 1944, the United States Army Air Forces undertook an intense strategic bombing campaign, using incendiary bombs, burning Japanese cities in an effort to pulverize Japan's industry and shatter its morale. The Operation Meetinghouse raid on Tokyo on the night of March 9–10, 1945, led to the deaths of approximately 100,000 civilians. Approximately 350,000–500,000 civilians died in 66 other Japanese cities as a result of the incendiary bombing campaign on Japan. Concurrent to these attacks, Japan's vital coastal shipping operations were severely hampered with extensive aerial mining by the U.S.'s Operation Starvation. Regardless, these efforts did not succeed in persuading the Japanese military to surrender. In mid-August 1945, the United States dropped nuclear weapons on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. These atomic bombings were the first and only such weapons used against another nation in warfare. These two bombs killed approximately 120,000 to 140,000 people in a matter of minutes, and as many as a result of nuclear radiation in the following weeks, months and years. The bombs killed as many as 140,000 people in Hiroshima and 80,000 in Nagasaki by the end of 1945.

Re-entry of the Soviet Union[]

In spite of Soviet–Japanese Neutrality Pact, at the Yalta agreement in February 1945, the US, the UK, and the USSR had agreed that the USSR would enter the war on Japan within three months of the defeat of Germany in Europe. This Soviet–Japanese War led to the fall of Japan's Manchurian occupation, Soviet occupation of South Sakhalin island, and a real, imminent threat of Soviet invasion of the home islands of Japan. This was a significant factor for some internal parties in the Japanese decision to surrender to the US[11] and gain some protection, rather than face simultaneous Soviet invasion as well as defeat by the US. Likewise, the superior numbers of the armies of the Soviet Union in Europe was a factor in the US decision to demonstrate the use of atomic weapons to the USSR, just as the Allied victory in Europe was evolving into division of Germany and Berlin, the division of Europe with the Iron Curtain and the subsequent Cold War.

Surrender and occupation of Japan[]

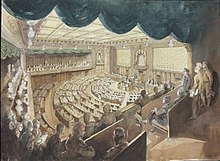

Having ignored (mokusatsu) the Potsdam Declaration, the Empire of Japan surrendered and ended World War II, after the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the declaration of war by the Soviet Union. In a national radio address on August 15, Emperor Hirohito announced the surrender to the Japanese people by Gyokuon-hōsō. A period known as Occupied Japan followed after the war, largely spearheaded by United States General of the Army Douglas MacArthur to revise the Japanese constitution and de-militarize Japan. The Allied occupation, with economic and political assistance, continued well into the 1950s. Allied forces ordered Japan to abolish the Meiji Constitution and enforce the Constitution of Japan, then rename the Empire of Japan as Japan on May 3, 1947.[12] Japan adopted a parliamentary-based political system, while the Emperor changed to symbolic status.

American General of the Army Douglas MacArthur later commended the new Japanese government that he helped establish and the new Japanese period when he was about to send the American forces to the Korean War:

The Japanese people, since the war, have undergone the greatest reformation recorded in modern history. With a commendable will, eagerness to learn, and marked capacity to understand, they have, from the ashes left in war's wake, erected in Japan an edifice dedicated to the supremacy of individual liberty and personal dignity; and in the ensuing process there has been created a truly representative government committed to the advance of political morality, freedom of economic enterprise, and social justice. Politically, economically, and socially Japan is now abreast of many free nations of the earth and will not again fail the universal trust. ... I sent all four of our occupation divisions to the Korean battlefront without the slightest qualms as to the effect of the resulting power vacuum upon Japan. The results fully justified my faith. I know of no nation more serene, orderly, and industrious, nor in which higher hopes can be entertained for future constructive service in the advance of the human race.

For historian John W. Dower:

In retrospect, apart from the military officer corps, the purge of alleged militarists and ultranationalists that was conducted under the Occupation had relatively small impact on the long-term composition of men of influence in the public and private sectors. The purge initially brought new blood into the political parties, but this was offset by the return of huge numbers of formerly purged conservative politicians to national as well as local politics in the early 1950s. In the bureaucracy, the purge was negligible from the outset. ... In the economic sector, the purge similarly was only mildly disruptive, affecting less than sixteen hundred individuals spread among some four hundred companies. Everywhere one looks, the corridors of power in postwar Japan are crowded with men whose talents had already been recognized during the war years, and who found the same talents highly prized in the 'new' Japan.[13]

Post war[]

Repatriation of Japanese from overseas[]

There was a significant level of emigration to the overseas territories of the Japanese Empire during the Japanese colonial period, including Korea,[14] Taiwan, Manchuria, and Karafuto.[15] Unlike emigrants to the Americas, Japanese going to the colonies occupied a higher rather than lower social niche upon their arrival.[16]

In 1938, there were 309,000 Japanese in Taiwan.[17] By the end of World War II, there were over 850,000 Japanese in Korea[18] and more than 2 million in China,[19] most of whom were farmers in Manchukuo (the Japanese had a plan to bring in 5 million Japanese settlers into Manchukuo).[20]

In the census of December 1939, the total population of the South Seas Mandate was 129,104, of which 77,257 were Japanese. By December 1941, Saipan had a population of more than 30,000 people, including 25,000 Japanese.[21] There were over 400,000 people living on Karafuto (southern Sakhalin) when the Soviet offensive began in early August 1945. Most were of Japanese or Korean extraction. When Japan lost the Kuril Islands, 17,000 Japanese were expelled, most from the southern islands.[22]

After World War II, most of these overseas Japanese repatriated to Japan. The Allied powers repatriated over 6 million Japanese nationals from colonies throughout Asia.[23] On the other hand, some remained overseas involuntarily, as in the case of orphans in China or prisoners of war captured by the Red Army and forced to work in Siberia.[24]

War crimes[]

Many political and military Japanese leaders were convicted for war crimes before the Tokyo tribunal and other Allied tribunals in Asia. However, all members of the imperial family implicated in the war, such as Emperor Shōwa, were excluded from criminal prosecutions by Douglas MacArthur. The Japanese military before and during World War II committed numerous atrocities against civilian and military personnel. Its surprise attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, prior to a declaration of war and without warning killed 2,403 neutral military personnel and civilians and wounded 1,247 others.[25][26] Large scale massacres, rapes, and looting against civilians were committed, most notably the Sook Ching and the Nanjing Massacre, and the use of around 200,000 "comfort women", who were said to be forced to serve as prostitutes for the Japanese military.[27]

The Imperial Japanese Army also engaged in the execution and harsh treatment of Allied military personnel and POWs. Biological experiments were conducted by Unit 731 on prisoners of war as well as civilians; this included the use of biological and chemical weapons authorized by Emperor Shōwa himself.[28] According to the 2002 International Symposium on the Crimes of Bacteriological Warfare, the number of people killed in Far East Asia by Japanese germ warfare and human experiments was estimated to be around 580,000.[29] The members of Unit 731, including Lieutenant General Shirō Ishii, received immunity from General MacArthur in exchange for germ warfare data based on human experimentation. The deal was concluded in 1948.[30][31] The Imperial Japanese Army frequently used chemical weapons. Because of fear of retaliation, however, those weapons were never used against Westerners, but against other Asians judged "inferior" by imperial propaganda.[32] For example, the Emperor authorized the use of toxic gas on 375 separate occasions during the Battle of Wuhan from August to October 1938.[33]

See also[]

- Imperial Japanese Army during the Pacific War

- Imperial Japanese Navy in World War II

- Japanese colonial empire

- List of territories occupied by Imperial Japan

- Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere

References[]

Citations[]

- ^ United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. "World War II in the Pacific". Holocaust Encyclopedia. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- ^ Gill, G. Hermon (1957). Royal Australian Navy 1939–1942. Australia in the War of 1939–1945. Series 2 – Navy. 1. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. p. 485. LCCN 58037940. Archived from the original on 25 May 2009. Retrieved 16 June 2015.

- ^ Morton, Louis. "Japan's Decision for War". U.S. Army Center Of Military History. Retrieved 5 May 2018.

- ^ Hotta, Eri (2013). Japan 1941 : Countdown to Infamy. New York: Knpf. ISBN 978-0307739742.

- ^ Dave Flitton (1994). Battlefield: Pearl Harbor (Documentary). Event occurs at 8 minutes, 40 seconds – via distributor: PBS.

- ^ Newman, T. (2018, February 28). Biological weapons and bioterrorism: Past, present, and future. Retrieved from https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/321030.php

- ^ https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/321030.php. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ^ L, Klemen (1999–2000). "Forgotten Campaign: The Dutch East Indies Campaign 1941–1942". Archived from the original on July 26, 2011.

- ^ Jump up to: a b [1]

- ^ [2]

- ^ Racing the Enemy: Stalin, Truman, and the Surrender of Japan Tsuyoshi Hasegawa Belknap Press (Oct. 30 2006) ISBN 978-0674022416

- ^ "Chronological table 5 1 December 1946 - 23 June 1947". National Diet Library. Retrieved September 30, 2010.

- ^ J. W. Dower, Japan in War & Peace, New press, 1993, p. 11

- ^ "Japanese Periodicals in Colonial Korea".

- ^ Japanese Immigration Statistics Archived October 15, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, DiscoverNikkei.org

- ^ Lankov, Andrei (March 23, 2006). "The Dawn of Modern Korea (360): Settling Down". The Korea Times. Retrieved December 18, 2006.

- ^ Grajdanzev, A. J. (1 January 1942). "Formosa (Taiwan) Under Japanese Rule". Pacific Affairs. 15 (3): 311–324. doi:10.2307/2752241. JSTOR 2752241.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on October 13, 1999. Retrieved 2009-11-03.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) The Life Instability of Intermarried Japanese Women in Korea

- ^ Killing of Chinese in Japan concerned, China Daily

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on December 23, 2008. Retrieved 2008-12-20.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) Prasenjit Duara: The New Imperialism and the Post-Colonial Developmental State: Manchukuo in comparative perspective

- ^ "A Go: Another Battle for Sapian". Archived from the original on December 23, 2008.

- ^ http://www.american.edu/TED/ice/kurile.htm. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ^ When Empire Comes Home : Repatriation and Reintegration in Postwar Japan by Lori Watt, Harvard University Press

- ^ "Russia Acknowledges Sending Japanese Prisoners of War to North Korea". Mosnews.com. April 1, 2005. Archived from the original on November 13, 2006. Retrieved February 23, 2007.

- ^ Yuma Totani (April 1, 2009). The Tokyo War Crimes Trial: The Pursuit of Justice in the Wake of World War II. Harvard University Asia Center. p. 57.

- ^ Stephen C. McCaffrey (September 22, 2004). Understanding International Law. AuthorHouse. pp. 210–229.

- ^ "Abe questions sex slave 'coercion'". BBC News. March 2, 2007. Retrieved May 2, 2010.

- ^ Yoshiaki Yoshimi and Seiya Matsuno, Dokugasusen Kankei Shiryō II (Materials on poison gas Warfare II), Kaisetsu, Hōkan 2, Jūgonen sensô gokuhi shiryōshū, Funi Shuppankan, 1997, pp. 25–29

- ^ Daniel Barenblatt, A Plague upon Humanity, 2004, pp. xii, 173.

- ^ Hal Gold, Unit 731 Testimony, 2003, p. 109.

- ^ Drayton, Richard (May 10, 2005). "An Ethical Blank Cheque: British and U.S. mythology about the second world war ignores our own crimes and legitimises Anglo-American war making" Archived January 11, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. The Guardian.

- ^ Yuki Tanaka, Poison Gas, the Story Japan Would Like to Forget, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, October 1988, p. 16-17

- ^ Y. Yoshimi and S. Matsuno, Dokugasusen Kankei Shiryô II, Kaisetsu, Jugonen Sensô Gokuhi Shiryoshu, 1997, p.27-29

Sources[]

- Jansen, Marius; John Whitney Hall; Madoka Kanai; Denis Twitchett (1989). The Cambridge History of Japan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-22352-0.

- Jansen, Marius B. (2002). The Making of Modern Japan. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-00334-9. OCLC 44090600

- 20th-century military history of Japan

- Empire of Japan

- Japan in World War II

- Military history of Japan

- Wars involving Japan

- Shōwa period