Jim Croce

Jim Croce | |

|---|---|

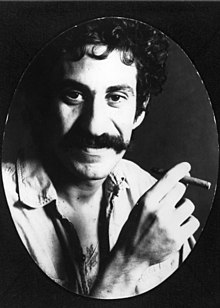

Croce in 1972, photographed by Ingrid Croce | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | James Joseph Croce |

| Born | January 10, 1943 South Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Died | September 20, 1973 (aged 30) Natchitoches, Louisiana |

| Genres | Folk, soft rock |

| Occupation(s) | Singer, songwriter |

| Instruments | Vocals, acoustic guitar |

| Years active | 1966–1973 |

| Labels | Capitol/EMI, ABC, Saja/Atlantic |

| Website | jimcroce |

James Joseph Croce (/ˈkroʊtʃi/; January 10, 1943 – September 20, 1973) was an American folk and rock singer-songwriter. Between 1966 and 1973, he released five studio albums and numerous singles. During this period, Croce took a series of odd jobs to pay bills while he continued to write, record, and perform concerts. After he formed a partnership with songwriter and guitarist Maury Muehleisen his fortunes turned in the early 1970s. His breakthrough came in 1972; his third album, You Don't Mess Around with Jim, produced three charting singles, including "Time in a Bottle", which reached No. 1 after his death. The follow-up album, Life and Times, contained the song "Bad, Bad Leroy Brown", which was the only No. 1 hit he had during his lifetime.

On September 20, 1973, at the height of his popularity and the day before the lead single to his fifth album, I Got a Name, was released, Croce and five others died in a plane crash. His music continued to chart throughout the 1970s following his death. Croce's wife, Ingrid Croce, was his early songwriting partner. She continued to write and record after his death and their son A. J. Croce became a singer-songwriter in the 1990s.

Early life[]

Croce was born January 10, 1943,[1] in South Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, to James Albert Croce (April 14, 1914 - March 8, 1972) and Flora Mary (Babusci) Croce (May 28, 1913 - December 22, 2000), Italian Americans from Trasacco and Balsorano in Abruzzo and Palermo in Sicily.[2][3]

Croce grew up in Upper Darby, Pennsylvania, a suburb of Philadelphia, and attended Upper Darby High School. Graduating in 1960, he studied at Malvern Preparatory School for a year before enrolling at Villanova University, where he majored in psychology and minored in German.[4][5] Croce received a Bachelor of Science in Social Studies degree in 1965. He was a member of the Villanova Singers and the Villanova Spires. When the Spires performed off-campus or made recordings, they were known as The Coventry Lads.[6] Croce was also a student disc jockey at WKVU, which has since become WXVU.[7][8][9]

Career[]

Early career[]

Croce did not take music seriously until he studied at Villanova, where he formed bands and performed at fraternity parties, coffee houses, and universities around Philadelphia, playing "anything that the people wanted to hear: blues, rock, a cappella, railroad music ... anything." Croce's band was chosen for a foreign exchange tour of Africa, the Middle East, and Yugoslavia. He later said, "We just ate what the people ate, lived in the woods, and played our songs. Of course they didn't speak English over there but if you mean what you're singing, people understand." On November 29, 1963, Croce met his future wife, Ingrid Jacobson, at the Philadelphia Convention Hall during a hootenanny, where he was judging a contest.

Croce released his first album, Facets, in 1966, with 500 copies pressed. The album had been financed with a $500 ($3,988 in 2020 dollars[10]) wedding gift from Croce's parents, who set a condition that the money must be spent to make an album. They hoped that he would give up music after the album failed, and use his college education to pursue a "respectable" profession.[11] However, the album proved a success, with every copy sold.

1960s[]

Croce married Jacobson in 1966, and converted to Judaism, as his wife was Jewish. He and Ingrid were married in a traditional Jewish ceremony.[12] He enlisted in the Army National Guard in New Jersey that same year to avoid being drafted and deployed to Vietnam, and served on active duty for four months, leaving for duty a week after his honeymoon.[13] Croce, who was not good with authority, had to go through basic training twice.[14] He said he would be prepared if "there's ever a war where we have to defend ourselves with mops."

From the mid-1960s to early 1970s, Croce performed with his wife as a duo. At first, their performances included songs by artists such as Ian & Sylvia, Gordon Lightfoot, Joan Baez, and Arlo Guthrie, but in time they began writing their own music. During this time, Croce got his first long-term gig, at a suburban bar and steakhouse in Lima, Pennsylvania, called The Riddle Paddock. His set list covered several genres, including blues, country, rock and roll, and folk.

In 1968, the Croces were encouraged by record producer Tommy West to move to New York City. The couple spent time in the Kingsbridge section of the Bronx and recorded their first album with Capitol Records. During the next two years, they drove more than 300,000 miles (480,000 km),[15] playing small clubs and concerts on the college concert circuit promoting their album Jim & Ingrid Croce.

Becoming disillusioned by the music business and New York City, they sold all but one guitar to pay the rent and returned to the Pennsylvania countryside, settling in an old farm in Lyndell, where he played for $25 a night ($167 in 2020 dollars[10]), which was not enough money to live on. Croce was forced to take odd jobs such as driving trucks, construction work, and teaching guitar to pay the bills while continuing to write songs, often about the characters he would meet at the local bars and truck stops and his experiences at work; these provided the material for such songs as "Big Wheel" and "Workin' at the Car Wash Blues."[16]

1970s[]

The Croces returned to Philadelphia and Croce decided to be "serious" about becoming a productive member of society. "I'd worked construction crews, and I'd been a welder while I was in college. But I'd rather do other things than get burned." His determination to be "serious" led to a job at a Philadelphia R&B AM radio station, WHAT, where he translated commercials into "soul". "I'd sell airtime to Bronco's Poolroom and then write the spot: 'You wanna be cool, and you wanna shoot pool ... dig it.'"

In 1970, Croce met classically trained pianist-guitarist and singer-songwriter Maury Muehleisen from Trenton, New Jersey, through producer Joe Salviuolo. Salviuolo and Croce had been friends when they studied at Villanova University, and Salviuolo had met Muehleisen when he was teaching at Glassboro State College in New Jersey. Salviuolo brought Croce and Muehleisen together at the production office of Tommy West and Terry Cashman in New York City. Croce at first backed Muehleisen on guitar, but gradually their roles reversed, with Muehleisen adding a lead guitar to Croce's music.[citation needed]

When Jim Croce and Ingrid discovered they were going to have a child, Croce became more determined to make music his profession. He sent a cassette of his new songs to a friend and producer in New York City in the hope that he could get a record deal. When their son Adrian James (A.J.) was born in September 1971, Ingrid became a stay-at-home mom while Jim went on the road to promote his music.

In 1972, Croce signed a three-record contract with ABC Records, releasing two albums, You Don't Mess Around with Jim and Life and Times. The singles "You Don't Mess Around with Jim", "Operator (That's Not the Way It Feels)", and "Time in a Bottle" all received airplay. Also that year, the Croce family moved to San Diego, California. Croce began appearing on television, including his national debut on American Bandstand[17] on August 12, The Tonight Show[18] on August 14, and The Dick Cavett Show on September 20 and 21.

Croce began touring the United States with Muehleisen, performing in large coffee houses, on college campuses, and at folk festivals. However, his financial situation remained precarious. The record company had fronted him the money to record, and much of his earnings went to pay back the advance. In February 1973, Croce and Muehleisen traveled to Europe, performing in London, Paris, Amsterdam, Monte Carlo, Zurich and Dublin and receiving positive reviews. Croce made television appearances on The Midnight Special, which he co-hosted on June 15, and The Helen Reddy Show on July 19. Croce's biggest single, "Bad, Bad Leroy Brown," reached Number 1 on the American charts in July.

From July 16 through August 4, Croce and Muehleisen returned to London and performed on The Old Grey Whistle Test, where they sang "Lover's Cross" and "Workin' at the Car Wash Blues" from their upcoming album I Got a Name. Croce finished recording the album just a week before his death. While on tour, he grew increasingly homesick and decided to take a break from music and settle with Ingrid and A.J. when his Life and Times tour ended.[19][20] In a letter to Ingrid which arrived after his death, Croce told her he had decided to quit music and stick to writing short stories and movie scripts as a career and withdraw from public life.[4][21]

Death[]

On the night of Thursday, September 20, 1973, during Croce's Life and Times tour and the day before his ABC single "I Got a Name" was released, Croce and all five others on board were killed when their chartered Beechcraft E18S crashed into a tree during takeoff from the Natchitoches Regional Airport in Natchitoches, Louisiana. Croce was 30 years old. Others killed in the crash were pilot Robert N. Elliott, Croce's bandmate Maury Muehleisen, comedian George Stevens, manager and booking agent Kenneth D. Cortese, and road manager Dennis Rast.[22][23][24] An hour before the crash, Croce had completed a concert at Northwestern State University's Prather Coliseum in Natchitoches; he was flying to Sherman, Texas, for a concert at Austin College.

An investigation by the NTSB[25] named the probable cause as the pilot's failure to see the obstruction due to physical impairment and because fog reduced his vision. The 57-year-old Elliott suffered from severe coronary artery disease and had run three miles to the airport from a motel. He had an ATP certificate, 14,290 hours total flight time, and 2,190 hours in the Beech 18 type airplane.[25] A later investigation placed the sole blame on pilot error because of his downwind takeoff into a "black hole" of severe darkness, limiting his use of visual references.[26]

Croce was buried at Haym Salomon Memorial Park in Frazer, Pennsylvania.

Legacy[]

The album I Got a Name was released on December 1, 1973.[27] The posthumous release included three hits: "Workin' at the Car Wash Blues," "I'll Have to Say I Love You in a Song," and the title song, which had been used as the theme to the film The Last American Hero, which was released two months prior to his death. The album reached No. 2, and "I'll Have to Say I Love You in a Song" reached No. 9 on the singles chart.

While ABC had not originally released the song "Time in a Bottle" as a single, Croce's untimely death gave its lyrics, dealing with mortality and the wish to have more time, an additional resonance. The song subsequently received a large amount of airplay as an album track, and demand for a single release built. When it was eventually issued as a 7", it became his second and final No. 1 hit.[28] After the single had finished its two-week run at the top in early January 1974, the album You Don't Mess Around with Jim became No. 1 for five weeks.[29]

A greatest hits album entitled Photographs & Memories was released in 1974. Later posthumous releases have included Home Recordings: Americana, The Faces I've Been, Jim Croce: Classic Hits, Down the Highway, and DVD and CD releases of Croce's television performances, Have You Heard: Jim Croce Live. In 1990, Croce was inducted into the Songwriters Hall of Fame.[30]

Queen's 1974 album Sheer Heart Attack included the song "Bring Back That Leroy Brown", whose title and lyrics reference Croce's "Bad, Bad Leroy Brown".

In 2012, Ingrid Croce published a memoir about Croce entitled I Got a Name: The Jim Croce Story.[31]

In 1985, Ingrid Croce opened Croce's Restaurant & Jazz Bar, a project she and Jim had jokingly discussed over a decade earlier, in the historic Gaslamp Quarter in downtown San Diego. She owned and managed it until it closed on December 31, 2013. In December 2013, she opened Croce's Park West on 5th Avenue in the Bankers Hill neighborhood near Balboa Park. She closed this restaurant in January 2016.[32]

Croce's music has appeared in several popular movies and television shows, such as Invincible; The Hangover Part II; Django Unchained; X-Men: Days of Future Past; Logan; Hobbs & Shaw; I Know This Much Is True; New Girl; Prodigal Son; American Gods; and Stranger Things.

Discography[]

- Facets (1966)

- Jim & Ingrid Croce (1969)

- You Don't Mess Around with Jim (1972)

- Life and Times (1973)

- I Got a Name (1973)

References[]

- ^ "UPI Almanac for Friday, Jan. 10, 2020". United Press International. January 10, 2020. Archived from the original on January 15, 2020. Retrieved February 1, 2020.

… singer Jim Croce in 1943

- ^ Kening, Dan; O'Shea, David; Paris, Jay (June 1991). Too Young to Die. Publications International, Limited. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-88176-932-6. Retrieved August 19, 2011.

- ^ "James Joseph Croce". Geni.com.

James Albert Croce son of Pasquale Anthony Croce born May 14, 1888, in Trasacco (Abruzzo) and Carmella Croce born June 24, 1894, in Palermo (Sicily). Flora Mary Croce (Babusci) daughter of Massimo Babusci born August 13, 1884, in Trasacco (Abruzzo), and Bernice Babusci (Ippolito or Ippoliti) born circa 1888 in Balsorano (Abruzzo).

- ^ Jump up to: a b Cohen, Alex; Martínez, A (October 8, 2012). "New book looks at singer-songwriter Jim Croce's too-short life". 89.3 KPCC (Interview). Take Two. Southern California Public Radio. Retrieved April 11, 2014.

- ^ Hoekstra, Dave (December 16, 2012). "Jim Croce's hit had roots in boot camp". Chicago Sun-Times. Chicago: Sun-Times Media, LLC. Retrieved April 11, 2014.

- ^ "Inquirer Anniversary: Croces capture time in a bottle". The Philadelphia Inquirer. August 10, 2009. Archived from the original on August 13, 2009. Retrieved November 27, 2011. Alt URL

- ^ Villanova Parents' Connection newsletter (Spring 2007).

- ^ Grottini, Kyle J. "Croce, James Joseph (Jim)". Pennsylvania Center for the Book. Archived from the original on June 11, 2010. Retrieved May 16, 2010.

- ^ Stevens, Candace (September 21, 2006). "Time to tune in to Villanova's own WXVU". The Villanovan (January 18, 2010 ed.). Archived from the original on July 6, 2013. Retrieved July 6, 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b 1634 to 1699: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy ofthe United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700-1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How much is that in real money?: a historical price index for use as a deflator of money values in the economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved January 1, 2020.

- ^ "Jim Croce News". music.yahoo.com. April 8, 2004. Retrieved August 24, 2012.

- ^ Elizabeth Applebaum (1998). "Article: Photographs And Memories, A story of love, music and conversion". The Detroit Jewish News. The Northern Music Group, Inc. Retrieved April 11, 2014.

- ^ "Jim Croce". The Philadelphia Inquirer. August 13, 1967.

- ^ Wiser, Carl (May 1, 2007). "Ingrid Croce: Songwriter Interviews". Songfacts.com. Retrieved April 11, 2014.

- ^ Croce's Restaurant- San Diego. Croces.com. Retrieved July 11, 2011.

- ^ Croce, Ingrid; Croce, Jim. Jim Croce Anthology (Songbook): The Stories Behind the Songs.

- ^ americanbandstandperformerlist

- ^ johnnycarson.com

- ^ Weber, Bryan (2014). "Article". Jim Croce- The Official Site. Archived from the original on August 7, 2012. Retrieved April 11, 2014.

- ^ Devenish, Colin (August 20, 2003). "Croce's Lost Recordings Due". Rolling Stone. Retrieved April 11, 2014.

- ^ Everitt, Richard:Falling Stars: Air Crashes that Filled Rock and Roll Heaven (2004)

- ^ "Recording star, 5 others killed in crash of plane". Spokesman-Review. (Spokane, Washington). Associated Press. September 22, 1973. p. 9.

- ^ "Rock group killed". The Michigan Daily. (Ann Arbor). Associated Press. September 22, 1973. p. 2.

- ^ "Celebrity Plane Crashes". Check-Six.com. Archived from the original on July 14, 2011. Retrieved November 27, 2011.

- ^ Jump up to: a b NTSB Identification: FTW74AF017; 14 CFR Part 135 Nonscheduled operation of Robert Airways; Aircraft: Beech E18S, registration: N50JR (Report). National Transportation Safety Board.gov. September 20, 1973.

- ^ Circuit, Fifth (August 14, 1980). "Croce v. Bromley Corporation". F2d (623). Openjurist.org: 1084. Retrieved July 11, 2011. Missing

|author1=(help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Jim Croce Album I Got A Name". VH1.com. Retrieved November 27, 2011.

- ^ Whitburn, Joel. The Billboard Book of Top 40 Hits, 7th edition, Billboard Books, 2000, p. 159.

- ^ Whitburn, Joel. The Billboard Book of Top Pop Albums 1955–1985, Record Research Inc., 1985, p. 88, 505.

- ^ "Songwriters Hall of Fame – Jim Croce". Songwriters Hall of Fame. Retrieved July 11, 2011.

- ^ Croce, Ingrid n; Rock, Jimmy (2012). I Got a Name: The Jim Croce Story. Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-82123-3.

- ^ Adams, Andie (January 25, 2016). "Croce's Park West Closes for Good". NBC San Diego. Retrieved March 11, 2016.

External links[]

- Jim Croce official website

- "Wall of Fame". Upper Darby High School. Retrieved April 20, 2021.

- Jim Croce at Find a Grave

- Jim Croce discography at Discogs

- 1943 births

- 1973 deaths

- Accidental deaths in Louisiana

- American male singer-songwriters

- American rock singers

- American rock songwriters

- American soft rock musicians

- Victims of aviation accidents or incidents in the United States

- Accidents and incidents involving the Beechcraft Model 18

- Villanova University alumni

- Capitol Records artists

- ABC Records artists

- American folk rock musicians

- American people of Italian descent

- Burials in Pennsylvania

- Converts to Judaism from Roman Catholicism

- United States Army soldiers

- American rock guitarists

- American pop guitarists

- American folk guitarists

- American folk singers

- Jewish American songwriters

- EMI Records artists

- Atlantic Records artists

- American pop rock singers

- 20th-century American singers

- Rhythm guitarists

- American acoustic guitarists

- American male guitarists

- Jewish rock musicians

- Malvern Preparatory School alumni

- Singers from Pennsylvania

- People from L'Aquila

- Songwriters from Pennsylvania

- Jewish folk singers

- 20th-century American guitarists

- Guitarists from Philadelphia

- 20th-century male singers

- People from Malvern, Pennsylvania

- Victims of aviation accidents or incidents in 1973

- Musicians killed in aviation accidents