Joe Cronin

| Joe Cronin | |||

|---|---|---|---|

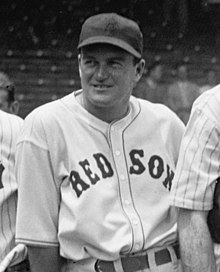

Cronin with the Boston Red Sox in 1937 | |||

| Shortstop / Manager | |||

| Born: October 12, 1906 San Francisco, California | |||

| Died: September 7, 1984 (aged 77) Osterville, Massachusetts | |||

| |||

| MLB debut | |||

| April 29, 1926, for the Pittsburgh Pirates | |||

| Last MLB appearance | |||

| April 19, 1945, for the Boston Red Sox | |||

| MLB statistics | |||

| Batting average | .301 | ||

| Hits | 2,285 | ||

| Home runs | 170 | ||

| Runs batted in | 1,424 | ||

| Managerial record | 1,236–1,055 | ||

| Winning % | .540 | ||

| Teams | |||

| As player

As manager

| |||

| Career highlights and awards | |||

| Member of the National | |||

| Induction | 1956 | ||

| Vote | 78.76% (tenth ballot) | ||

Joseph Edward Cronin (October 12, 1906 – September 7, 1984) was an American professional baseball player, manager and executive. He played in Major League Baseball (MLB) as a shortstop, most notably as a member of the Boston Red Sox. Cronin spent over 48 years in baseball, culminating with 14 years as president of the American League (AL).

During his 20-year playing career (1926–1945), Cronin played for the Pittsburgh Pirates, Washington Senators and the Boston Red Sox; he was a player-manager for 13 seasons (1933–1945), and served as manager for two additional seasons (1946–1947). A seven-time All-Star, Cronin became the first American League player to become an All-Star with two teams; he was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1956.

Early life[]

Cronin was born in Excelsior District of San Francisco, California. The 1906 San Francisco earthquake had cost his Irish Catholic parents almost all of their possessions.[1][2] Cronin attended Sacred Heart High School. He played several sports as a child and he won a city tennis championship for his age group when he was 14. As he was not greatly interested in school, Cronin's grades improved only when the San Francisco Seals of the Pacific Coast League began giving away tickets to students with good conduct and attendance. At the time, the nearest MLB team was nearly 2,000 miles (3,200 km) from San Francisco.[3]

Major league career[]

As a player[]

Baseball promoter Joe Engel, who scouted for the Senators and managed the Chattanooga Lookouts at Engel Stadium, originally signed Cronin. Engel first spotted Cronin playing in Kansas City. "I knew I was watching a great player", Engel said. "I bought Cronin at a time he was hitting .221. When I told Clark Griffith what I had done, he screamed, 'You paid $7,500 for that bum? Well, you didn't buy him for me. You bought him for yourself. He's not my ballplayer – he's yours. You keep him and don't either you or Cronin show up at the ballpark.'"[4]

In 1930, Cronin had a breakout year, batting .346 with 13 home runs and 126 RBI. Cronin won both the AL Writers' MVP (the forerunner of the BBWAA MVP, established in 1931) and the AL Sporting News MVP. His 1931 season was also outstanding, with him posting a .306 average, 12 home runs, and 126 RBIs. Cronin led the Senators to the 1933 World Series and later married Griffith's niece, Mildred Robertson.

As a player-manager and manager[]

Cronin was named player-manager of the Senators in 1933, a post he would hold for two years. In his first year, he led the Senators to what would be their last pennant in Washington.

While Cronin was on his honeymoon with Mildred in his hometown of San Francisco, he got a message from Griffith–the Boston Red Sox had offered the Senators their starting shortstop, Lyn Lary, in return for Cronin and $250,000. Red Sox owner Tom Yawkey also offered Cronin a five-year contract as player-manager. Well aware of the Senators' perennial financial problems (Griffith had no income apart from the Senators), Cronin accepted the trade.[5] Cronin remained as player-manager of the Red Sox until 1945, then remained solely as manager until 1947.

As early as 1938, it was apparent that Cronin was nearing the end of his playing career. Red Sox farm director Billy Evans thought he had found Cronin's successor in Pee Wee Reese, the star shortstop for the Louisville Colonels of the Triple-A American Association. He was so impressed by Reese that he was able to talk Yawkey into buying the Colonels and making them the Red Sox' top farm club. However, when Yawkey and Evans asked Cronin to scout Reese, Cronin realized he was scouting his replacement. Believing that he was still had enough left to be a regular player, Cronin deliberately downplayed Reese's talent and suggested that the Red Sox trade him. Reese was eventually traded to the Brooklyn Dodgers, where he went on to a Hall of Fame career.[6] As it turned out, Evans' and Yawkey's initial concerns about Cronin were valid. His last year as a full-time player was 1941; after that year, he never played more than 76 games per season.

Even when World War II saw dozens of young players either enlist or be drafted, Cronin limited his playing appearances to cameo roles as a utility infielder and pinch-hitter.[5] On June 17, 1943, Cronin sent himself into pinch hit in both games of a doubleheader and hit a home run each time.

In April 1945, he broke his leg in a game against the Yankees. He sat out the remainder of the season, and retired as a player for good at the end of the year.[5]

Over his career, Cronin batted .300 or higher eight times, as well as driving in 100 runs or more eight times. He finished with a .301 average, 170 home runs, and 1,424 RBIs.

As a manager, he compiled a 1,236–1,055 record and won two American League pennants (in 1933 and 1946). His 1933 Senators dropped the 1933 World Series to the New York Giants, and his 1946 Red Sox–the franchise's first pennant winner in 28 years–lost the 1946 World Series to the St. Louis Cardinals.

As a general manager[]

At the end of the 1947 season, Cronin succeeded Eddie Collins as general manager of the Red Sox and held the post for over 11 years, through mid-January 1959. The Red Sox challenged for the AL pennant in 1948 and 1949, finishing second by a single game each season, thanks to Cronin's aggressive trades. In his first off-season, he acquired shortstop Vern Stephens and pitchers Ellis Kinder and Jack Kramer from the St. Louis Browns; all played major roles for the 1948 Red Sox, who finished in a flatfooted tie for the pennant with the Cleveland Indians but lost a one-game tie-breaker. Kinder and Stephens were centerpieces of the Red Sox' 1949–1950 contenders as well. In the former year, they were edged out by the Yankees during the regular season's final weekend; in the latter, they finished third but came within four games of the league-leading Yanks.

As it turned out, 1950 was the last hurrah for the Red Sox during Cronin's tenure as general manager. With the exception of Ted Williams (who missed most of the 1952–1953 seasons while serving in the Korean War), the core of the 1946–1950 team aged quickly and the Red Sox faced a significant rebuilding job starting in 1952. Cronin's acquisition of future American League Most Valuable Player Jackie Jensen from Washington in 1954 represented a coup, but the club misfired on several "bonus babies" who never lived up to their potential. The Red Sox posted winning season records for all but two of Cronin's 11 seasons as general manager, but from 1951 through 1958 they lagged behind the AL pennant-winners (except for 1954, the Yankees) by an average of almost 18 games. Then, beginning in 1959, the Red Sox began a skein of eight straight below-.500 and second-division campaigns. They would not be a factor in a pennant race again until the "Impossible Dream" season of 1967.

Most attention has been focused on Cronin and Yawkey's refusal to integrate the Red Sox roster; by January 1959, when Cronin's tenure as general manager ended, the Red Sox were the only team in the big leagues that had never fielded an African-American or Afro-Latin American player. Notably, Cronin once passed on signing a young Willie Mays and never traded for an African-American player.[7] The Red Sox did not break the baseball color line until six months after Cronin's departure for the AL presidency, when they promoted Pumpsie Green, a utility infielder, from their Triple-A affiliate, the Minneapolis Millers, in July 1959.

As AL president[]

In January 1959, Cronin was elected president of the American League, the first former player to be so elected and the fourth full-time chief executive in the league's history. When he replaced the retiring Will Harridge, who became board chairman, Cronin moved the league's headquarters from Chicago to Boston. Cronin served as AL president until December 31, 1973, when he was succeeded by Lee MacPhail.

During Cronin's 15 years in office, the Junior Circuit expanded from eight to 12 teams, adding the Los Angeles Angels and expansion Washington Senators in 1961[8] and the Kansas City Royals and Seattle Pilots in 1969.

It also endured four franchise shifts: the relocation of the original Senators club (owned by Cronin's brother-in-law and sister-in-law, Calvin Griffith and Thelma Griffith Haynes) to Minneapolis–Saint Paul, creating the Minnesota Twins (1961); the shift of the Athletics from Kansas City to Oakland (1968); the transfer of the Pilots after only one season in Seattle to Milwaukee as the Brewers (1970); and the transplantation of the expansion Senators after 11 seasons in Washington, D.C., to Dallas–Fort Worth as the Texas Rangers (1972). The Angels also moved from Los Angeles to adjacent Orange County in 1966 and adopted a regional identity, in part because of the dominance of the National League Dodgers, who were the Angels' landlords at "Chavez Ravine" (Dodger Stadium) from 1962–1965. Of the four expansion teams that joined the league beginning in 1961, three abandoned their original host cities within a dozen years (the Pilots after only one season), and only one team—the Royals—remained in its original municipality. Two of the charter members of the old eight-team league, the Chicago White Sox and Cleveland Indians, also suffered significant attendance woes and were targets of relocation efforts by other cities.

In addition, the AL found itself at a competitive disadvantage compared with the National League during Cronin's term. With strong teams in larger markets and a host of new stadiums, the NL outdrew the AL for 33 consecutive years (1956–1988).[9] In 1973, Cronin's final season as league president, the NL attracted 55 percent of total MLB attendance, 16.62 million vs. 13.38 million total fans, despite the opening of Royals Stadium in Kansas City and the American League's adoption of the designated hitter rule, which was designed to spark scoring and fan interest. While the National League held only an 8–7 edge in World Series play during the Cronin era, it dominated the Major League Baseball All-Star Game, going 15–3–1 in the 19 games played from 1959–1973.

After the 1968 season, Cronin drew headlines when he fired AL umpires Al Salerno and Bill Valentine, ostensibly for poor performance; however, it later surfaced that the two officials were fired for attempting to organize an umpires' union. Neither man was reinstated (Valentine became a successful minor league front-office executive), but the Major League Umpires Association was formed anyway, two years later.[10] However, in 1966, Cronin was hailed for integrating MLB's umpiring staff with the promotion of veteran minor league arbiter Emmett Ashford to the American League.[11]

| |

| Joe Cronin's number 4 was retired by the Boston Red Sox in 1984. |

Hall of Fame[]

Joe Cronin was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame (with Hank Greenberg) in 1956.

Career statistics[]

| G | AB | R | H | 2B | 3B | HR | RBI | BB | AVG | OBP | SLG | FLD% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2,124 | 7,579 | 1,233 | 2,285 | 515 | 118 | 170 | 1,424 | 1,059 | .301 | .390 | .468 | .953 |

Managerial record[]

| Team | Year | Regular season | Postseason | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Games | Won | Lost | Win % | Finish | Won | Lost | Win % | Result | ||

| WAS | 1933 | 152 | 99 | 53 | .651 | 1st in AL | 1 | 4 | .200 | Lost World Series (NYG) |

| WAS | 1934 | 152 | 66 | 86 | .434 | 7th in AL | – | – | – | – |

| WAS total | 304 | 165 | 139 | .543 | 1 | 4 | .200 | |||

| BOS | 1935 | 153 | 78 | 75 | .510 | 4th in AL | – | – | – | – |

| BOS | 1936 | 154 | 74 | 80 | .481 | 6th in AL | – | – | – | – |

| BOS | 1937 | 152 | 80 | 72 | .526 | 5th in AL | – | – | – | – |

| BOS | 1938 | 149 | 88 | 61 | .591 | 2nd in AL | – | – | – | – |

| BOS | 1939 | 151 | 89 | 62 | .589 | 2nd in AL | – | – | – | – |

| BOS | 1940 | 154 | 82 | 72 | .532 | 5th in AL | – | – | – | – |

| BOS | 1941 | 154 | 84 | 70 | .545 | 2nd in AL | – | – | – | – |

| BOS | 1942 | 152 | 93 | 59 | .612 | 2nd in AL | – | – | – | – |

| BOS | 1943 | 152 | 68 | 84 | .447 | 7th in AL | – | – | – | – |

| BOS | 1944 | 154 | 77 | 77 | .500 | 4th in AL | – | – | – | – |

| BOS | 1945 | 154 | 71 | 83 | .461 | 7th in AL | – | – | – | – |

| BOS | 1946 | 154 | 104 | 50 | .675 | 1st in AL | 3 | 4 | .429 | Lost World Series (STL) |

| BOS | 1947 | 154 | 83 | 71 | .539 | 3rd in AL | – | – | – | – |

| BOS total | 1987 | 1071 | 916 | .539 | 3 | 4 | .429 | |||

| Total | 2291 | 1236 | 1055 | .540 | 4 | 8 | .333 | |||

Death[]

In the last months of his life, Cronin struggled with cancer that had invaded his prostate and bones; he suffered a great deal of bone pain as a result.[12] Cronin came to Fenway Park for one of his last public appearances when his jersey number 4 was retired by the Red Sox on May 29, 1984. He died at the age of 77 on September 7, 1984, at his home in Osterville, Massachusetts.[13] He is buried in St. Francis Xavier Cemetery in nearby Centerville.

Legacy[]

At the number retirement ceremony shortly before Cronin's death, teammate Ted Williams commented on how much he respected Cronin as a father and a man. Cronin was also remembered as a clutch hitter. Manager Connie Mack once commented, "With a man on third and one out, I'd rather have Cronin hitting for me than anybody I've ever seen, and that includes Cobb, Simmons and the rest of them."[14]

In 1999, he was a nominee for the Major League Baseball All-Century Team.[15]

See also[]

- Boston Red Sox Hall of Fame

- Bay Area Sports Hall of Fame

- List of Major League Baseball career hits leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career doubles leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career triples leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career runs scored leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career runs batted in leaders

- List of Major League Baseball annual doubles leaders

- List of Major League Baseball annual triples leaders

- List of Major League Baseball players to hit for the cycle

- List of Major League Baseball player-managers

- List of Major League Baseball managers by wins

Notes[]

- ^ Corcoran, Dennis (2010). Induction Day at Cooperstown: A History of the Baseball Hall of Fame Ceremony. McFarland. p. 68. ISBN 978-0786444168.

- ^ Armour, Mark. "Joe Cronin". Society for American Baseball Research. Retrieved 16 July 2016.

- ^ Armour, pp. 9-10.

- ^ Rosen, Charley (2012). The Emerald Diamond: How the Irish Transformed America's Favorite Pastime. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0062089915.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Mark Armour (2015). "Joe Cronin". Society for American Baseball Research.

- ^ Neyer, Rob (2006). Rob Neyer's Big Book of Baseball Blunders. New York City: Fireside. ISBN 0-7432-8491-7.

- ^ Edes, Gordon, George Digby and Willie Mays: The One Who Got Away. ESPN Boston, May 3, 2014

- ^ McCue, Andy, and Thompson, Eric (2011), "Mismanagement 101: The American League's Expansion of 1961." The National Pastime 2011, Society for American Baseball Research

- ^ Studenmund, Dave; Tamer, Greg (2004). The Hardball Times 2004 Baseball Annual. The Hardball Times. ISBN 9781411617179.

- ^ Armour, Mark (2009). "A Tale of Two Umpires: When Al Salerno and Bill Valentine Were Thrown Out of the Game". sabr.org. Society for American Baseball Research. Retrieved July 14, 2017.

- ^ Armour, Mark (2007). "Emmett Ashford". sabr.org. Society for American Baseball Research. Retrieved July 14, 2017.

- ^ Armour, p. 330.

- ^ "Joe Cronin, baseball legend, American League president". The Morning Call. September 8, 1984. Retrieved November 29, 2014.

- ^ "Joe Cronin, an ex-executive and star player in baseball". The New York Times. September 8, 1984. Retrieved November 29, 2014.

- ^ "The All-Century Team". MLB.com. Retrieved October 31, 2013.

References[]

- Armour, Mark (2010). Joe Cronin: A Life in Baseball. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0803229968.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Joe Cronin. |

- Joe Cronin at the Baseball Hall of Fame

- Career statistics and player information from Baseball-Reference, or Fangraphs, or Retrosheet

- Joe Cronin managerial career statistics at Baseball-Reference.com

- Joe Cronin at Find a Grave

^Joe Cronin at SABR (Baseball BioProject)

- 1906 births

- 1984 deaths

- American League All-Stars

- American League presidents

- American people of Irish descent

- Baseball players from San Francisco

- Boston Red Sox executives

- Boston Red Sox managers

- Boston Red Sox players

- Deaths from cancer in Massachusetts

- Johnstown Johnnies players

- Kansas City Blues (baseball) players

- Major League Baseball general managers

- Major League Baseball player-managers

- Major League Baseball players with retired numbers

- Major League Baseball shortstops

- National Baseball Hall of Fame inductees

- New Haven Profs players

- People from Osterville, Massachusetts

- Pittsburgh Pirates players

- Sportspeople from Barnstable County, Massachusetts

- Washington Senators (1901–1960) managers

- Washington Senators (1901–1960) players