Johann Caspar Weidenmann

Johann Caspar Weidenmann (13 October 1805 – 6 June 1850) was a Swiss painter and draughtsman. He was one of the first European artists to travel across Algeria, in 1838 and 1839.

Life[]

Childhood and Adolescence[]

Weidenmann was born in Winterthur (canton of Zürich). His father, Hans Kaspar Weidenmann (1778–1859), was the city's "fountain master", responsible for the water supply network. His mother, Anna Dorothea, née Hirzel (1780–1821) was a teacher. She died when Johann Caspar, the eldest of her nine children, was only 16 years old. A year later, Cleophea Scheitlin – a sister of the scholar and author – became the children's stepmother.

Johann Caspar, a "lively, cheerful" boy, took his first drawing lessons from 1818 to 1820 at the boys' school in Winterthur. From 1820 to 1822 he served his apprenticeship as a decorator. He also learned to copy Old Masters, and he painted his first portraits, which earned him recognition as a talented young artist. Therefore, several wealthy citizens of his home town donated substantial sums so that he could go to Italy for his further artistic education.[1] (Of the portraits below, only the drawing of his brother Friedrich as a boy was created before 1824. The rest date from 1831/1833.)

The father: "fountain master" Hans Kaspar Weidenmann

The amiable stepmother: Cleophea Weidenmann-Scheitlin (1780–1857)

The little brother: Friedrich Weidenmann (1814–1882)

Friedrich around 1831/33

Italy[]

From 1824 until 1829, Weidenmann lived in Florence; later in Rome, 1829–1831 and 1833–1837. In 1831 he had to return to Winterthur for two years, to earn money as a portrait painter.

In Florence, he led quite a solitary life for almost five years, training his artistic skills on his own by copying famous paintings at the city's art galleries. In Rome, however, he quickly made friends with other young artists from German-speaking countries and from Scandinavia, who held regular meetings at their social club, visited each other's studios and frequented the city's pubs. Among them were Thomas Fearnley and Salomon Corrodi as well as the sculptors Herman Wilhelm Bissen and . Joseph Anton Koch and Johann Christian Reinhart were the Grand Old Men revered by the young painters.

Weidenmann relished the freedoms that Rome offered to young artists, but he was suffering from continual financial pressures. He felt forced to paint subjects that did not particularly interest him, but which he was occasionally able to sell in his home town: genre scenes, portraits and copies of Old Masters. He would have loved to create large-format history paintings, but for lack of commissions, he never got beyond drawing sketches of historical scenes. Fortunately, landscape painting offered a delightful alternative. In summer, he left Rome, either alone or with some friends, and went hiking in the Monti Sabini, the Alban Hills and the Monti Lepini. Painting and drawing landscapes, people and animals En plein air became more and more important to him. "I love doing it; perhaps I do it too often" he wrote in 1836.[2]

In the Monti Lepini range, near Civitavecchia

Italian Peasant Woman with a Broom, National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.

Italian girl

Roman woman

At the studio: The models are inspecting the painting while the artist is taking a break (1836)

Algeria[]

Weidenmann was also acquainted with Horace Vernet, the director of the French Academy in Rome, who had visited Algeria in 1833. Deeply impressed by the paintings Vernet had brought back from Algeria and by the stories he told the young painters about this country, Weidenmann eventually decided to go to North Africa himself in 1838. But whereas Vernet had undertaken an official French mission, Weidenmann was one of the first European artists to travel to Algeria on his own, out of thirst for adventure. He stayed there for a year and nine months (from March 1838 to December 1839) – longer than any other European artist of his generation. More than 30 years later, Albert Lebourg was the first to surpass this length of stay.[3]

From Algiers, Weidenmann travelled east: first on an overcrowded ship to Bône (Annaba); from there on horseback to Constantine, which had only been captured by French troops seven months earlier. He made good use of every opportunity to get to know the countryside and the local people and to paint; his travel expenses were met by portraying Europeans. He stayed in Constantine for almost five months. On his exhausting journey back to Bône, he fell ill with malaria and had to spend two months on the sick bed. In the following year he was able to travel again and to paint to his heart's content, mainly in the fertile Mitidja plain south of Algiers. But in November 1839, the security situation deteriorated so much that he was forced to leave Algeria. In 1840/41 he probably stayed in Italy again; then he returned to his home country.[4]

Coffee shop in Constantine, 1838

Market at Coudiat-Aty near Constantine, 1838

Bab-Azun, a suburb of Algiers, 1838/39, Winterthur Museum of Art

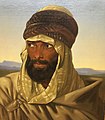

Bedouin from the Sahara, 1838/39

Interior of a house in Algiers, 1838/39, Winterthur Museum of Art

Last Years[]

In Switzerland, the paintings and drawings Weidenmann had brought home from North Africa were admired by everybody and praised by art experts. At the second Swiss art exhibition in May 1842, Weidenmann was allowed to exhibit 99 works, more than any other painter.[5] But he couldn't sell anything. So once again, he had to accept commissions to paint portraits. He also worked as a private teacher in Winterthur; his most talented student was August Weckesser. In 1847/48 Weidenmann lived in Munich for about a year, where he became a member of the city's artist society. Soon after his return to Winterthur, he co-founded the artist society in his home town.[6]

His stay in Algeria had severely affected his health; he suffered from chronic bouts of fever. On 6 June 1850 he died at the age of only 44.[7] "His funeral was attended by more people than those of the richest and most respected of his fellow-citizens, which shows how much he was grieved for, both as a man and as an artist."[8]

Dying heron (Weidenmann's last work, 1849/50; unfinished)

Work[]

Paintings and drawings[]

Weidenmann created over 1000 works, mainly landscapes, portraits and genre paintings. His style is very realistic; he drew and painted his subjects from a detached perspective. Almost all of the landscapes were created En plein air. Weidenmann depicted the scenery of North Africa, the foreign people and their culture – hitherto completely unknown to most Europeans – exactly as he saw them, without romanticizing. The Portrait of a Camel holds a special position in art history: Never before had an exotic animal been immortalized in such a portrait, boldly staged against a neutral background.[9]

The artist society Weidenmann had co-founded bought some of his works; and a year after his death, the civic community of Winterthur purchased his artistic estate: 35 oil paintings as well as 60 drawings and watercolours.[10] These works are still owned by the City of Winterthur and the Winterthur Museum of Art.

Portrait of a camel in Algeria, 1838/39, Winterthur Museum of Art

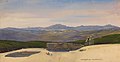

Scenery near Constantine, 1838, Winterthur Museum of Art

Constantine, 1838, Winterthur Museum of Art

Fountain near Algiers, 1838/39

Group of palm trees in the Mitidja plain, 1839, Winterthur Museum of Art

Letters[]

From Italy and from Algeria, Weidenmann wrote letters to his family, friends and acquaintances in Winterthur. 22 letters have been preserved, which he wrote from Italy to his patron and paternal friend Salomon Brunner, between 1827 and 1838.[11] In addition, an essay published six years after Weidenmann's death contains long extracts from letters he wrote while he was travelling across Algeria.[12]

- Extracts from Weidenmann's letters: PDF file (in German, 15 pages).

Sources[]

- Häsli, Richard (1966). Johann Caspar Weidenmann. Ein Winterthurer Maler 1805–1850. Winterthur: Stadtbibliothek.

- Hafner, Albert (1856). "Johann Kaspar Weidenmann und seine algerischen Studien." Neujahrsblatt von der Bürgerbibliothek zu Winterthur. Winterthur: Ziegler, pp. 325–340.

- Fehlmann, Marc (2014). "Johann Caspar Weidenmann." Homegrown. Winterthurer Malerei durch die Jahrhunderte. Winterthur: Museum Oskar Reinhart, pp. 18–19 and p. 48.

Notes[]

- ^ Häsli (1966), pp. 7–9.

- ^ Häsli (1966), pp. 9–25.

- ^ Häsli (1966), pp. 53–55 and p. 59.

- ^ Häsli (1966), pp. 26–33; Hafner (1856), pp. 330–339.

- ^ Häsli (1966), p. 34. – Swiss art exhibition 1842, list of displayed works (Weidenmann's works are listed on the last two pages.)

- ^ Häsli (1966), pp. 33–37.

- ^ Häsli (1966), p. 39.

- ^ Hafner (1856), p. 340.

- ^ Häsli (1966), pp. 83–87; Fehlmann (2014), p. 19 and p. 48.

- ^ Fink, Paul (ed.) (1921). Briefe von Maler J. C. Weidenmann aus Italien. Winterthur: Ziegler, p. 5.

- ^ Fink, Paul (ed.) (1921).

- ^ Hafner, Albert (1856)

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Johann Caspar Weidenmann. |

- Works by Weidenmann at the Winterthur Museum of Art

- "Weidenmann, Johann Caspar". SIKART Lexicon on art in Switzerland.

- Johann Caspar Weidenmann in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

- 1805 births

- 1850 deaths

- 19th-century Swiss painters

- 19th-century male artists

- Swiss portrait painters

- Swiss landscape painters

- Swiss male painters

- People from Winterthur