John Houseman

John Houseman | |

|---|---|

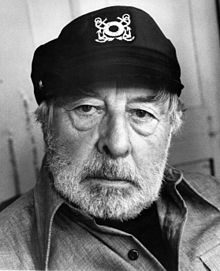

Houseman in The Fog | |

| Born | Jacques Haussmann September 22, 1902 Bucharest, Romania |

| Died | October 31, 1988 (aged 86) Malibu, California, U.S. |

| Education | Clifton College |

| Occupation | Actor, producer |

| Years active | 1930–1988 |

| Spouse(s) | Joan Courtney (m. 1952–1988) |

| Children | 2 |

John Houseman (born Jacques Haussmann; September 22, 1902 – October 31, 1988) was a Romanian-born British-American actor and producer of theatre, film, and television. He became known for his highly publicized collaboration with director Orson Welles from their days in the Federal Theatre Project through to the production of Citizen Kane and his collaboration, as producer of The Blue Dahlia, with writer Raymond Chandler on the screenplay. He is perhaps best known for his role as Professor Charles W. Kingsfield in the film The Paper Chase (1973), for which he won the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor. He reprised his role as Kingsfield in the 1978 television series adaptation.

Houseman was also known for his commercials for the brokerage firm Smith Barney. He had a distinctive English accent, a product of his schooling.

Early life[]

Houseman was born Jacques Haussmann on September 22, 1902, in Bucharest, Romania, the son of May (née Davies) and Georges Haussmann, who ran a grain business.[1] His mother was British, from a Christian family of Welsh and Irish descent.[2] His father was an Alsatian-born Jew.[3][4][5][6] He was educated in England at Clifton College,[7] became a British subject, and worked in the grain trade in London before emigrating to the United States in 1925, where he took the stage name of John Houseman. He became a United States citizen in 1943.[8]

Theatre producer[]

Houseman worked as a speculator in the international grain markets, only turning to the theater following the 1929 stock market crash.

On Broadway he co-wrote Three and One (1933) and And Be My Love (1934). Composer Virgil Thomson recruited him to direct Four Saints in Three Acts (1934), Thomson's collaboration with Gertrude Stein.[9] He later directed The Lady from the Sea (1934), Valley Forge (1934).[10]

Collaboration with Orson Welles[]

In 1934, Houseman was looking to cast Panic, a play he was producing based on a drama by Archibald MacLeish concerning a Wall Street financier whose world crumbles about him when consumed by the crash of 1929. Although the central figure is a man in his late fifties, Houseman became obsessed by the notion that a young man named Orson Welles he had seen in Katharine Cornell's production of Romeo and Juliet was the only person qualified to play the leading role. Welles consented and, after preliminary conversations, agreed to leave the play he was in after a single night to take the lead in Houseman's production. Panic opened at the Imperial Theatre on March 15, 1935. Among the cast was Houseman's ex-wife, Zita Johann, who had co-starred with Boris Karloff three years earlier in Universal's The Mummy.

Although the play opened to indifferent notices and ran for a mere three performances, it nevertheless led to the forging of a theatrical team, a fruitful but stormy partnership in which Houseman said Welles "was the teacher, I, the apprentice."

He supervised the direction of Walk Together Chillun in 1936.

Federal Theatre Project[]

In 1936, the Federal Theatre Project of the Works Progress Administration put unemployed theatre performers and employees to work. The Negro Theatre Unit of the Federal Theatre Project was headed by Rose McClendon, a well-known black actress, and Houseman, a theatre producer. Houseman describes the experience in one of his memoirs:

Within a year of its formation, the Federal Theatre had more than fifteen thousand men and women on its payroll at an average wage of approximately twenty dollars a week. During the four years of its existence its productions played to more than thirty million people in more than two hundred theatres as well as portable stages, school auditoriums and public parks the country over.[11]

Macbeth (1936)[]

Houseman immediately hired Welles and assigned him to direct Macbeth for the FTP's Negro Theater Unit, a production that became known as the "Voodoo Macbeth", as it was set in the Haitian court of King Henri Christophe (and with voodoo witch doctors for the three Weird Sisters) and starred Jack Carter in the title role. The incidental music was composed by Virgil Thomson. The play premiered at the Lafayette Theatre on April 14, 1936, to enthusiastic reviews and remained sold out for each of its nightly performances. The play was regarded by critics and patrons as an enormous, if controversial, success. After 10 months with the Negro Theater Project, however, Houseman felt he was faced with the dilemma of risking his future:

... on a partnership with a 20-year-old boy in whose talent I had unquestioning faith but with whom I must increasingly play the combined and tricky roles of producer, censor, adviser, impresario, father, older brother and bosom friend.[11]

Houseman later produced for the Negro Theatre Unit Turpentine (1936) without Welles.

In 1936, Houseman and Welles were running a WPA unit in midtown Manhattan for classic productions called Project No. 891. Their first production was Christopher Marlowe's Tragical History of Dr. Faustus which Welles directed while also playing the title role.

Houseman and Welles put on Horse Eats Hat (1936). Houseman, without Welles, helped in the direction of Leslie Howard's production of Hamlet (1936).

The Cradle Will Rock (1937)[]

In June 1937, Project No. 891 produced their most controversial work with The Cradle Will Rock. Written by Marc Blitzstein the musical was about Larry Foreman, a worker in Steeltown (played in the original production by Howard Da Silva), which is run by the boss, Mister Mister (played in the original production by Will Geer). The show was thought to have had left-wing and unionist sympathies (Foreman ends the show with a song about "unions" taking over the town and the country), and became legendary as an example of a "censored" show. Shortly before the show was to open, FTP officials in Washington announced that no productions would open until after July 1, 1937, the beginning of the new fiscal year.

In his memoir, Run-Through, Houseman wrote about the circumstances surrounding the opening night at the Maxine Elliott Theatre. All the performers had been enjoined not to perform on stage for the production when it opened on July 14, 1937. The cast and crew left their government-owned theatre and walked 20 blocks to another theatre, with the audience following. No one knew what to expect; when they got there Blitzstein himself was at the piano and started playing the introduction music. One of the non-professional performers, Olive Stanton, who played the part of Moll, the prostitute, stood up in the audience, and began singing her part. All the other performers, in turn, stood up for their parts. Thus the "oratorio" version of the show was born. Apparently, Welles had designed some intricate scenery, which ended up never being used. The event was so successful that it was repeated several times on subsequent nights, with everyone trying to remember and reproduce what had happened spontaneously the first night. The incident, however, led to Houseman being fired and Welles's resignation from Project No. 891.[citation needed]

Mercury Theatre[]

That same year, 1937, after detaching themselves from the Federal Theatre Project, Houseman and Welles did The Cradle Will Rock as an independent production on Broadway. They also founded the acclaimed New York drama company, the Mercury Theatre. Houseman wrote of their collaboration at this time:

On the broad wings of the Federal eagle, we had risen to success and fame beyond ourselves as America's youngest, cleverest, most creative and audacious producers to whom none of the ordinary rules of the theater applied.[11]

Armed with a manifesto written by Houseman[12] declaring their intention to foster new talent, experiment with new types of plays, and appeal to the same audiences that frequented the Federal Theater the company was designed largely to offer plays of the past, preferably those that "...seem to have emotion or factual bearing on contemporary life." The company mounted several notable productions, the most remarkable being its first commercial production of Julius Caesar. Houseman called the decision to use modern dress "an essential element in Orson's conception of the play as a political melodrama with clear contemporary parallels."

Houseman and Welles later presented (1938), Heartbreak House (1938) and Danton's Death (1938).

Radio[]

Beginning in the summer of 1938, the Mercury Theatre was featured in a weekly dramatic radio program on the CBS network, initially promoted as First Person Singular before gaining the official title The Mercury Theatre on the Air. An adaptation of Treasure Island was scheduled for the program's first broadcast, for which Houseman worked feverishly on the script. However, a week before the show was to air, Welles decided that a program far more dramatic was required. To Houseman's horror, Treasure Island was abandoned in favor of Bram Stoker's Dracula, with Welles playing the infamous vampire. During an all night session at Perkins' Restaurant, Welles and Houseman hashed out a script.[citation needed]

The Mercury Theatre on the Air featured an impressive array of talents, including Agnes Moorehead, Bernard Herrmann, and George Coulouris.

"The War of the Worlds" (1938)[]

The Mercury Theatre on the Air subsequently became famous for its notorious 1938 radio adaptation of H. G. Wells' The War of the Worlds, which had put much of the country in a panic.[13] By all accounts, Welles was shocked by the panic that ensued. According to Houseman, "he hadn't the faintest idea what the effect would be". CBS was inundated with calls; newspaper switchboards were jammed.

Without Welles, Houseman staged The Devil and Daniel Webster (1939).

Film producer[]

Too Much Johnson (1938)[]

While Houseman was teaching at Vassar College, he produced Welles' never-completed second short film, Too Much Johnson (1938). The film was never publicly screened and no print of the film was thought to have survived. Footage was rediscovered in 2013.[14]

Citizen Kane (1941)[]

The Welles-Houseman collaboration continued in Hollywood. In the spring of 1939, Welles began preliminary discussions with RKO's head of production, George Schaefer, with Welles and his Mercury players being given a two-picture deal, in which Welles would produce, direct, perform, and have full creative control of his projects.

For his motion picture debut, Welles first considered adapting Joseph Conrad's Heart of Darkness for the screen. A 200-page script was written. Some models were constructed, while the shooting of initial test footage had begun. However, little, if anything, had been done either to whittle down the budgetary difficulties or begin filming. When RKO threatened to eliminate the payment of salaries by December 31 if no progress had been made, Welles announced that he would pay his cast out of his own pocket. Houseman proclaimed that there wasn't enough money in their business account to pay anyone. During a corporate dinner for the Mercury crew, Welles exploded, calling his partner a "bloodsucker" and a "crook". As Houseman attempted to leave, Welles began hurling dish heaters at him, effectively ending both their partnership and friendship.

Houseman later, however, played a pivotal role in ushering Citizen Kane (1941), which starred Welles. Welles telephoned Houseman asking him to return to Hollywood to "babysit" screenwriter Herman J. Mankiewicz while he completed the script, and keep him away from alcohol. Still drawn to Welles, as was virtually everyone in his sphere, Houseman agreed. Although Welles took credit for the screenplay of Kane, Houseman stated that the credit belonged to Mankiewicz, an assertion that led to a final break with Welles. Houseman took some credit himself for the general shaping of the story line and for editing the script. In an interview with Penelope Huston for Sight & Sound magazine (Autumn, 1962) Houseman said that the writing of Citizen Kane was a delicate subject:

I think Welles has always sincerely felt that he, single-handed, wrote Citizen Kane and everything else that he has directed — except, possibly, the plays of Shakespeare. But the script of Kane was essentially Mankiewicz's. The conception and the structure were his, all the dramatic Hearstian mythology and the journalistic and political wisdom he had been carrying around with him for years and which he now poured into the only serious job he ever did in a lifetime of film writing. But Orson turned Kane into a film: the dynamics and the tensions are his and the brilliant cinematic effects — all those visual and aural inventions that add up to make Citizen Kane one of the world's great movies — those were pure Orson Welles.

In 1975, during an interview with Kate McCauley, Houseman stated that film critic Pauline Kael in her essay "Raising Kane", had caused an "idiotic controversy" over the issue: "The argument is Orson's own fault. He wanted to be given all the credit because he's a hog. Actually, it is his film. So it's a ridiculous argument."[15][16]

Return to the theatre[]

After he and Welles went their separate ways, Houseman went on to direct The Devil and Daniel Webster (1939) and Liberty Jones (1941) and produced the Mercury Theatre's stage production of Native Son (1941) on Broadway, directed by Welles.

David O. Selznick[]

In Hollywood he became a vice-president of David O. Selznick Productions. His most notable achievement during that time was helping adapt and produce the adaptation of Jane Eyre (1943) which starred Joan Fontaine and Welles.

World War II[]

In the aftermath of the attack on Pearl Harbor, Houseman quit his job and became the head of the overseas radio division of the Office of War Information (OWI), working for the Voice of America whilst also managing its operations in New York City.[17]

Paramount[]

In 1945 Houseman signed a contract with Paramount Pictures to produce movies. His first credit for that studio was The Unseen (1945). He followed it with Miss Susie Slagle's (1945) and The Blue Dahlia (1946), both with Veronica Lake. The latter, starring Alan Ladd and written by Raymond Chandler, has become a classic.

He left Paramount and returned to Broadway to direct Lute Song (1946) with Mary Martin.

Back in Hollywood he produced Letter from an Unknown Woman (1948) for Max Ophuls at Universal.

RKO[]

Houseman went to RKO where he produced They Live by Night (1948) the directorial debut of Nicholas Ray. He also did The Company She Keeps (1949) and On Dangerous Ground (1951).

He returned to Broadway to produce Joy to the World (1949) and King Lear (1950-51), the latter with Louis Calhern.

MGM[]

RKO's head of production had been Dore Schary. When Schary moved to MGM he offered Houseman a contract at the studio, which the producer accepted.

Houseman's stint at MGM began with Holiday for Sinners (1952); then he had a huge success with The Bad and the Beautiful (1952), directed by Vincente Minnelli. He followed it with the film adaptation of Julius Caesar (1953) (for which he received an Academy Award nomination for Best Picture)

Also popular was Executive Suite (1954), although Her Twelve Men (1954), Minnelli's The Cobweb (1955) and Fritz Lang's Moonfleet (1955) all lost money. So did Lust for Life (1956), a biopic directed by Minnelli of Vincent van Gogh, although it was extremely well-received critically.

Television and theatre[]

Houseman moved into television producing, notably doing The Seven Lively Arts (1957) and episodes of Playhouse 90.

He also returned to theatre, producing revivals of Measure for Measure (1957) and The Duchess of Malfi (1957).

Return to MGM[]

Houseman was enticed back to MGM as a producer, and given his own production company, John Houseman Productions. His films were All Fall Down (1962), Two Weeks in Another Town (1962) and In the Cool of the Day (1963).

Return to television[]

Houseman returned to television where he made The Great Adventure and (1964). He returned to Hollywood briefly to produce This Property Is Condemned (1966), then went back to TV for Evening Primrose (1966).

He went back to Broadway directing Pantagleize (1967).

Teaching[]

The Juilliard School and The Acting Company[]

Houseman became the founding director of the Drama Division at The Juilliard School, and held this position from 1968 until 1976.[18][19] The first graduating class in 1972 included Kevin Kline and Patti LuPone; subsequent classes under Houseman's leadership included Christopher Reeve, Mandy Patinkin, and Robin Williams.[20]

Unwilling to see that very first class disbanded upon graduation, Houseman and his Juilliard colleague Margot Harley formed them into an independent, touring repertory company they named the "Group 1 Acting Company."[21] The organization was subsequently renamed The Acting Company, and has been active for more than 40 years. Houseman served as the producing artistic director through 1986, and Harley has been the Company's producer since its founding.[22] Writing in The New York Times in 1996, Mel Gussow called it "the major touring classical theater in the United States."[23]

Theatre[]

Houseman continued to be involved in theatre, producing The School for Wives (1971), The Three Sisters (1973), The Beggar's Opera (1973), Scapin (1973), Next Time I'll Sing to You (1974), The Robber Bridegroom (1975), Edward II (1975), and The Time of Your Life (1975)

He directed The Country Girl (1972), Don Juan in Hell (1973), Measure for Measure (1973), and Clarence Darrow (1974) (with Henry Fonda).

In 1979, Houseman earned induction into the American Theater Hall of Fame[24]

Acting[]

Houseman had acted occasionally during the early part of his career and he had briefly appeared in Seven Days in May (1964).

Houseman first became widely known to the public for his Golden Globe and Academy Award-winning role as Professor Charles Kingsfield in the film The Paper Chase (1973). The film was a success and launched Houseman into an unexpected late career as a character actor.

Houseman played Energy Corporation Executive Bartholomew in the film Rollerball (1975), and was in the thrillers Three Days of the Condor (1975) and St Ives (1976).

Houseman appeared on TV in Fear on Trial (1975), The Adams Chronicles (1976), (1976), (1976) and Six Characters in Search of an Author (1976). Houseman was reunited with The Paper Chase co-star Lindsay Wagner in 1976's "Kill Oscar", a three-part joint episode of the popular science fiction series The Bionic Woman and The Six Million Dollar Man; he played the scientific genius Dr. Franklin.

He continued appearing on TV in Captains and the Kings (1976), The Displaced Person (1977), a version of Our Town (1977), Washington: Behind Closed Doors (1977), (1977), , (1978), The French Atlantic Affair (1978) and The Associates (1980).

In films he parodied Sydney Greenstreet in the Neil Simon film The Cheap Detective (1978) and was in Old Boyfriends (1980), John Carpenter's The Fog (1980), Wholly Moses! (1981) and My Bodyguard (1981).

Houseman briefly returned to producing with the TV movie Gideon's Trumpet (1980), which he also appeared in and Choices of the Heart (1983). He produced one more show on Broadway, The Curse of an Aching Heart (1982).

He acted in The Babysitter (1980), A Christmas Without Snow (1980), Ghost Story (1981), Mork & Mindy, Murder by Phone (1982) (second billed), Marco Polo (1982), and American Playhouse (1982).

Television star[]

Having played a Harvard Law School professor in the film The Paper Chase (1973), he reprised the role in a television series of the same name, which ran from 1978 to 1979 and 1983 to 1986. During that time, he received two Golden Globe nominations for "Best Actor in a TV Series — Drama".

In the 1980s Houseman became more widely known for his role as grandfather Edward Stratton II in Silver Spoons, which starred Rick Schroder, and for his commercials for brokerage firm Smith Barney, which featured the catchphrase, "They make money the old fashioned way... they earn it." Another was Puritan brand cooking oil, with "less saturated fat than the leading oil", featuring the famous 'tomato test'.

He played Jewish author Aaron Jastrow (loosely based on the real life figure of Bernard Berenson) in the highly acclaimed 1983 miniseries The Winds of War (receiving a fourth Golden Globe nomination). He declined to reprise the role when the sequel War and Remembrance was made into a miniseries (the role then went to Sir John Gielgud).

However he was in the miniseries A.D. (1984), Noble House (1986), and Lincoln (1986).

Final years and death[]

Later film appearances included Bright Lights, Big City (1988) and Another Woman (1988).

In 1988, he appeared in his last two roles—cameos in the films The Naked Gun: From the Files of Police Squad! and Scrooged. He played a driving instructor (whose mannerisms parodied many of his prior roles) in the former, and himself in the latter. Both films were released after his death.

On October 31, 1988, Houseman died at age 86 of spinal cancer at his home in Malibu, California.[25] He was cremated and his ashes were scattered at sea.

In popular culture[]

Houseman was portrayed by Cary Elwes in the Tim Robbins-directed film Cradle Will Rock (1999). Actor Eddie Marsan plays the role of Houseman in Richard Linklater's film Me & Orson Welles (2009). Houseman was played by actor Jonathan Rigby in the Doctor Who audio drama Invaders from Mars set around the War of the Worlds broadcast. Actor Sam Troughton portrayed Houseman in the 2020 film Mank.

Filmography[]

Film[]

As actor[]

| Year | Title | Role | Director | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1938 | Too Much Johnson | Duelist / Keystone Cop | Orson Welles | Also producer |

| 1964 | Seven Days in May | Vice-Adm. Farley C. Barnswell | John Frankenheimer | Uncredited |

| 1973 | The Paper Chase | Charles W. Kingsfield Jr. | James Bridges | Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor Golden Globe Award for Best Supporting Actor - Motion Picture National Board of Review Award for Best Supporting Actor New York Film Critics Circle Award for Best Supporting Actor (2nd place) |

| 1975 | Rollerball | Mr. Bartholomew | Norman Jewison | |

| Three Days of the Condor | Wabash | Sydney Pollack | ||

| 1976 | St. Ives | Abner Procane | J. Lee Thompson | |

| 1978 | The Cheap Detective | Jasper Blubber | Robert Moore | |

| 1979 | Old Boyfriends | Dr. Hoffman | Joan Tewkesbury | |

| 1980 | The Fog | Mr. Machen | John Carpenter | |

| Wholly Moses! | The Archangel | Gary Weis | ||

| My Bodyguard | Mr. Dobbs | Tony Bill | ||

| 1981 | Ghost Story | Sears James | John Irvin | |

| 1982 | Murder by Phone | Stanley Markowitz | Michael Anderson | |

| 1983 | A Rose for Emily | Narrator (voice) | Lyndon Chubbuck | Short film |

| 1988 | Bright Lights, Big City | Mr. Vogel | James Bridges | |

| Another Woman | Mr. Post | Woody Allen | ||

| Scrooged | Himself | Richard Donner | Cameo | |

| The Naked Gun: From the Files of Police Squad! | Driving Instructor | David Zucker | Uncredited cameo |

As producer[]

| Year | Title | Director | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1938 | Too Much Johnson | Orson Welles | |

| 1945 | The Unseen | Lewis Allen | As associate producer |

| 1946 | Miss Susie Slagle's | John Berry | |

| The Blue Dahlia | George Marshall | ||

| 1948 | Letter from an Unknown Woman | Max Ophüls | |

| They Live by Night | Nicholas Ray | ||

| 1951 | The Company She Keeps | John Cromwell | |

| On Dangerous Ground | Nicholas Ray | ||

| 1952 | Holiday for Sinners | Gerald Mayer | |

| The Bad and the Beautiful | Vincente Minnelli | ||

| 1953 | Julius Caesar | Joseph L. Mankiewicz | Nominated–Academy Award for Best Picture |

| 1954 | Executive Suite | Robert Wise | |

| Her Twelve Men | Robert Z. Leonard | ||

| 1955 | The Cobweb | Vincente Minnelli | |

| Moonfleet | Fritz Lang | ||

| 1956 | Lust for Life | Vincente Minnelli | |

| 1962 | All Fall Down | John Frankenheimer | |

| Two Weeks in Another Town | Vincente Minnelli | ||

| 1963 | In the Cool of the Day | Robert Stevens | |

| 1966 | This Property Is Condemned | Sydney Pollack |

Television[]

As actor[]

| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1975 | Great Performances | Dr. Fawcett | Episode: "Beyond the Horizon" |

| Fear on Trial | Mike Collins | Television film | |

| 1976 | The Adams Chronicles | Judge Richard Gridley | Miniseries; 1 episode |

| Truman at Potsdam | Winston Churchill | Television film | |

| Hazard's People | John Hazard | ||

| Six Characters in Search of an Author | The Director | ||

| The Six Million Dollar Man | Dr. Lee Franklin | Episode: "Kill Oscar: Part 2" | |

| The Bionic Woman | 2 episodes | ||

| Captains and the Kings | Judge Newell Chisholm | Miniseries; 2 episodes | |

| 1977 | The American Short Story | Father Flynn | Episode: "The Displaced Person" |

| Washington: Behind Closed Doors | Myron Dunn | Miniseries; 6 episodes | |

| The Best of Families | Himself (Host) | Miniseries | |

| Aspen | Joseph Merrill Drummond | Miniseries; 2 episodes | |

| 1978–86 | The Paper Chase | Charles W. Kingsfield Jr. | Main cast; Seasons 1–4

Golden Globe Award for Best Actor – Television Series Drama (1) |

| 1979 | The Last Convertible | Dr. Wetherell | Miniseries; 3 episodes |

| The French Atlantic Affair | Dr. Archady Clemens | ||

| 1980 | The Associates | Professor Kingsfield | Episode: "Eliot's Revenge" |

| Gideon's Trumpet | Earl Warren | Television film | |

| The Babysitter | Dr. Lindquist | ||

| A Christmas Without Snow | Ephraim Adams | ||

| 1982 | Mork & Mindy | Milt | Episode: "Mork, Mindy, and Mearth Meet MILT" |

| Marco Polo | Patriarch of Aquileia | Miniseries; 1 episode | |

| 1982–87 | Silver Spoons | Edward Stratton Jr. | Recurring role; Seasons 1–5 |

| 1983 | American Playhouse | Network Newscaster | Episode: "Network Newscaster" |

| The Winds of War | Aaron Jastrow | Miniseries; 7 episodes

Nominated–Golden Globe Award for Best Supporting Actor – Series, Miniseries or Television Film | |

| Freedom to Speak | Benjamin Franklin | Miniseries; 3 episodes | |

| 1985 | A.D. | Gamaliel | Miniseries; 5 episodes |

| 1988 | Noble House | Sir Geoffrey Allison | Miniseries; 4 episodes |

| Lincoln | Gen. Winfield Scott | Miniseries; 2 episodes |

As producer[]

| Year | Title | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1957–58 | The Seven Lively Arts | 10 episodes |

| 1958–59 | Playhouse 90 | 7 episodes |

| 1960 | Dillinger | Television film |

| 1963 | The Great Adventure | 3 episodes |

| 1966 | ABC Stage 67 | Episode: "Evening Primrose" |

| 1980 | Gideon's Trumpet | Television film

Nominated–Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Television Movie |

| 1983 | Choices of the Heart | Television film |

References[]

- ^ Current biography yearbook – H.W. Wilson Company – Google Books. 1984. Retrieved May 7, 2012.

- ^ Darrach, Brad (January 17, 1983). "John Houseman". People.com. Retrieved May 7, 2012.

- ^ Magill, Frank Northen (1977). Survey of Contemporary Literature. Salem Pr. Inc. p. 6535. ISBN 0-89356-050-2.

- ^ Houseman, John (1972). Run-Through: A Memoir. Simon and Schuster. p. 15.

- ^ "John Houseman". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ "John Houseman", New York Times Movies.

- ^ "Clifton College Register" Muirhead, J.A.O. p314, no 7281: Bristol; J.W Arrowsmith for Old Cliftonian Society; April, 1948

- ^ "John Houseman". Filmreference.com. Retrieved March 29, 2010.

- ^ Tommasini, Anthony. (1997) Virgil Thomson – Composer on the Aisle, pp.241–243.

- ^ The Broadway League. "John Houseman". Internet Broadway Database. Ibdb.com. Retrieved March 29, 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Houseman, John. Run-Through: A Memoir, New York, 1972.

- ^ "Orson Welles — Director — Films as Director:, Other Films:, Publications". Filmreference.com. Retrieved March 29, 2010.

- ^ "The Federal Theatre Project". Novaonline.nvcc.edu. Retrieved March 29, 2010.

- ^ Kehr, Dave (August 7, 2013), "Early Film by Orson Welles Is Rediscovered", New York Times

- ^ Kael, Pauline (February 20, 1971). "Raising Kane��I". The New Yorker. and Kael, Pauline (February 27, 1971). "Raising Kane—II". The New Yorker.

- ^ "John Houseman on "What happened to Orson Welles?"". Wellesnet: Orson Welles Web Resource. August 21, 2008. Retrieved February 17, 2018.

- ^ "The Beginning: An American Voice Greets the World". Voice of America.

- ^ Olmstead, Andrea (2002). Juilliard: A History. University of Illinois Press. p. 232. ISBN 9780252071065.

- ^ "A Brief History – About Juilliard". The Juilliard School. Retrieved June 3, 2012.

- ^ Klein, Alvin (July 12, 1992). "THEATER; From Juilliard to Shakespeare at a Pond". The New York Times.

- ^ Olmstead, Andrea (2002). Juilliard: A History. University of Illinois Press. p. 230. ISBN 9780252071065.

The success of The Acting Company's first season had greatly benefited the School and lifted the Drama Division's stock with Lincoln Center's Board.

Reprinting of the 1999 book, which described the relationship between the Juilliard School and The Acting Company at the time of the latter's founding. - ^ "About Us". The Acting Company. Retrieved March 2, 2014.

- ^ Gussow, Mel (January 30, 1996). "A Touring Troupe That Plays Classics On Main Street". The New York Times.

Seven years after Mr. Houseman's death, and after a steeplechase course of obstacles, the Acting Company endures as the major touring classical theater in the United States. Now under the sole leadership of Ms. Harley, the company takes plays to 45 cities from Orono, Me., to Sheridan, Wyo.

Descriptive article on the occasion of the Company's 25th anniversary. - ^ "Theater Hall of Fame Enshrines 51 Artists". The New York Times. November 19, 1979. Retrieved February 7, 2019.

- ^ "John Houseman, Actor and Producer, 86, Dies". The New York Times.

External links[]

- John Houseman at IMDb

- John Houseman at the Internet Broadway Database

- John Houseman at the TCM Movie Database

- John Houseman at AllMovie

- John Houseman at Find a Grave

- "The Theatre: Marvelous Boy" – Time Magazine May 9, 1938

- Interviews with Howard Koch on the infamous Mercury Theatre's War of the Worlds radio broadcast

- 1902 births

- 1988 deaths

- Male actors from Bucharest

- Deaths from cancer in California

- Deaths from spinal cancer

- American male film actors

- American theatre managers and producers

- American radio producers

- American radio writers

- American film producers

- American male screenwriters

- British male film actors

- 20th-century American male actors

- 20th-century British male actors

- People educated at Clifton College

- Juilliard School faculty

- Jewish theatre directors

- Federal Theatre Project administrators

- Best Supporting Actor Academy Award winners

- Best Supporting Actor Golden Globe (film) winners

- Voice of America people

- Romanian emigrants to the United Kingdom

- Naturalised citizens of the United Kingdom

- British emigrants to the United States

- British people of Jewish descent

- 20th-century American male writers

- 20th-century American screenwriters

- People of the United States Office of War Information