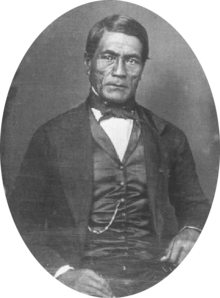

John Papa ʻĪʻī

John Papa ʻĪʻī | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | August 3, 1800 |

| Died | May 2, 1870 (aged 69) |

| Nationality | Kingdom of Hawaii |

| Spouse(s) | Sarai Hiwauli Kamaka Maleka Kaʻapā Maraea Kamaunauikea Kapuahi |

| Children | Irene ʻĪʻī Brown Holloway |

John (Ioane) Kaneiakama Papa ʻĪʻī (1800–1870) was a 19th-century educator, politician and historian in the Kingdom of Hawaii.

Life[]

ʻĪʻī was born 1800, in the month of Hilinehu, which he calculated to be August 3, in later life. He was born near the Hanaloa fishpond in Kūmelewai, Waipiʻo, ʻEwa, Oʻahu. His mother was Kalaikāne Wanaoʻa Pahulemu while he is considered to have two fathers (a tradition called poʻolua), either Kuaʻena Mālamaʻekeʻeke or Kaiwikokoʻole, although ʻĪʻī claimed the former as his father because he did not resemble Kaiwikokoʻole.[1] His family belonged to the Luluka branch of the Luahine line, hereditary kahu (caretaker) to the chiefs of Hawaii.[2] His cousin was .[3][4]

ʻĪʻī was raised under the traditional kapu system and trained from childhood for a life of service to the high chiefs. At the age of ten he was taken to Honolulu by his uncle Papa ʻĪʻī, a kahu of Kamehameha I, to become a companion and personal attendant to Prince Liholiho, who became King Kamehameha II in 1819. ʻĪʻī was close to Liholiho during the young heir's instruction in the conduct of government and ancient religious rites. His master died in 1823 in England.[5]

After Liholiho's death, ʻĪʻī continued to serve the rulers of Hawai‘i and including being kahu for Victoria Kamāmalu and hānai father of Mary Polly Paʻaʻāina. ʻĪʻī and his wife Sarai Hiwauli were selected to be kahu of the students at the Chiefs' Children's School in 1840.[6] Throughout his life he was in constant contact with the political, religious, and social concerns of the court, as well as the common people.[7] ʻĪʻī was among the first Hawaiians to study reading and writing with the missionaries, yet although he adopted Christian teachings, he retained a profound love and respect for the culture of his ancestors.[5]

ʻĪʻī served as a general superintendent of Oʻahu schools and was an influential member in the court of Kamehameha III. In 1842, he was appointed by the king to the Treasury Board. He served as a member of the Privy Council 1845–1859 and in 1846 was appointed to the Board of Land Commissioners. ʻĪʻī served in the House of Nobles from 1841 to 1870. In 1852, he represented the House of Nobles in the drafting of the Constitution and became the Speaker of the House of Nobles. He served as a member of the House of Representatives during the session of 1855. He served from 1848 as a superior court judge, and from 1852 to 1864 as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the Kingdom.[8] ʻĪʻī died of scarlet fever on May 2, 1870 at Mililani, his residence in Honolulu.[9]

Legacy[]

He left a first-hand account chronicle from 1866 until his death in a series of articles in the Hawaiian language newspaper Ka Nupepa Ku'oko'a.[7] These were translated by Mary Kawena Pukui and published in 1959 as "Fragments of Hawaiian History",[10] which describes life through his personal experiences under Kamehameha, and descriptions of the pattern of Hawaiian culture during a period of great significance in the history of the Hawaiian Kingdom.[5] A second edition was edited by Dorothy Barrère and published in 1983.[11]

His first marriage in 1822 was to , the widow of Haʻaloʻu, a chief executed for adultery with one of Kamehameha II's wives.[12] She died without surviving issue in 1856. His second marriage was to Kamaka, on July 9, 1857. Kamaka died between 1857 and 1861 and was buried with Sarai and a daughter either belonging to her or Sarai. He remarried for a third time to nineteen-year-old Maleka (Martha) Kaʻapā at Hilo, on August 1, 1861; she died of consumption a month afterward. On January 1, 1862, he married for final time to Maraea (Malaea) Kamaunauikea Kapuahi.[13] By this marriage, he had his only surviving child, Irene Haʻaloʻu Kahalelauko-a-Kamāmalu ʻĪʻī, born on October 1, 1869.[14][15] On September 30, 1886, Irene married Charles Augustus Brown and had sons George ʻĪʻī Brown (1887–1946), and Francis Hyde ʻĪʻī Brown (1892–1976); a daughter, Bernice Kamamalu (1894-1895), died young; a second daughter Rose Kaouinuiokalani (1895-1972) married Arthur Lewis Davis and had two sons.[16] Irene divorced Brown in 1898 and married Carl Sheldon Holloway on June 27, 1901. She died on August 26, 1922.[17] From his grandson, ʻĪʻī has many descendants including Kenneth Francis Brown.[18]

The lands that John ʻĪʻī had been awarded were put into a trust called the John ʻĪʻī Estate, Limited, which was the subject of a lawsuit due to ambiguity in the original will.[19][20]

References[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to John Papa ʻĪʻī. |

- ^ Brown 2014, pp. 49–56.

- ^ "II, John – LCA 8241 – Alii Award" (PDF). Kanaka Genealogy web site. Retrieved March 25, 2012.

- ^ Ii, Pukui & Barrère 1983, p. 22.

- ^ "John Papa ʻĪʻī". geni_family_tree. Retrieved 2021-01-12.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Bishop Museum Press Authors". Bishop Museum. Archived from the original on 2010-04-25. Retrieved 2009-10-27.

- ^ Dibble 1843, p. 328.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Michael Tsai (July 2, 2006). "John Papa ʻĪʻī". Honolulu Advertiser. Retrieved 2009-10-27.

- ^ "John Ii office record". state archives digital collections. state of Hawaii. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2009-10-27.

- ^ Brown 2014, p. 203.

- ^ Ii, Pukui & Barrère 1983, p. iii.

- ^ Ii, Pukui & Barrère 1983, p. iv.

- ^ Brown 2014, pp. 83–84.

- ^ Brown 2014, pp. 169–171.

- ^ Brown 2014, pp. 200–201.

- ^ "Irene Kahalelaukoa Holloway". geni_family_tree. Retrieved 2021-01-12.

- ^ Siddall 1917, p. 50.

- ^ Brown 2014, pp. 210–212.

- ^ Ii/Brown Family: Oral Histories 1999, p. A-1.

- ^ United States Circuit Court of Appeals (1913). "John Ii Estate, Limited et al. v. Brown et al.". The Federal reporter: with key-number annotations. 201. West Publishing Co. pp. 224–248.

- ^ Brown 2014, pp. 207–212.

References[]

- Brown, Marie Alohalani (December 2014). Facing the Spears of Change: the Life and Legacy of Ioane Kaneiakama Papa ʻĪʻī. Honolulu: University of Hawaii at Manoa. hdl:10125/101056.

- Center for Oral History, Social Science Research Institute, University of Hawaii at Manoa; Queen Emma Foundation (March 1999). Ii/Brown Family: Oral Histories. Honolulu: Center for Oral History, Social Science Research Institute, University of Hawaii at Manoa. hdl:10125/29803.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Dibble, Sheldon (1843). History of the Sandwich Islands. Lahainaluna: Press of the Mission Seminary.

- Ii, John Papa; Pukui, Mary Kawena; Barrère, Dorothy B. (1983). Fragments of Hawaiian History (2 ed.). Honolulu: Bishop Museum Press. ISBN 978-0-910240-31-4.

- Siddall, John William, ed. (1917). Men of Hawaii. 1. Honolulu: Honolulu Star-Bulletin.

Further reading[]

- Brown, Marie Alohalani (2016). Facing the Spears of Change: The Life and Legacy of John Papa ʻĪʻī. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-5848-3. OCLC 933722571.

- 1800 births

- 1870 deaths

- Hawaiian nobility

- Hawaiian Kingdom politicians

- Hawaiian Kingdom judges

- Members of the Hawaiian Kingdom House of Nobles

- Members of the Hawaiian Kingdom Privy Council

- Members of the Hawaiian Kingdom House of Representatives

- Historians of Hawaii

- Justices of the Hawaii Supreme Court

- Deaths from streptococcus infection

- Burials at Oahu Cemetery