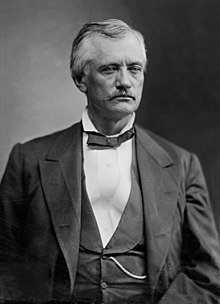

John Tyler Morgan

John Morgan | |

|---|---|

| |

| United States Senator from Alabama | |

| In office March 4, 1877 – June 11, 1907 | |

| Preceded by | George Goldthwaite |

| Succeeded by | John H. Bankhead |

| Personal details | |

| Born | John Tyler Morgan June 20, 1824 Athens, Tennessee, U.S. |

| Died | June 11, 1907 (aged 82) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1861–1865 |

| Rank | Brigadier General |

| Battles/wars | American Civil War |

John Tyler Morgan (June 20, 1824 – June 11, 1907) was a general in the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War, a six-term U.S. senator from the state of Alabama after the war. A slave holder before the Civil War,[1][2] he was a proponent of Jim Crow laws, states rights and racial segregation through the Reconstruction era. He was an expansionist, arguing for the annexation of Hawaii and for U.S. construction of an inter-oceanic canal in Central America.

Early life and career[]

Morgan was born in Athens, Tennessee into a family of Welsh origin whose ancestor, James B. Morgan[3] (1607–1704), settled in the Connecticut Colony. John T. Morgan was initially educated by his mother. In 1833, he moved with his parents to Calhoun County, Alabama, where he attended frontier schools and then studied law in Tuskegee with justice William Parish Chilton, his brother-in-law. After admission to the bar he established a practice in Talladega. Ten years later, Morgan moved to Dallas County and resumed the practice of law in Selma and Cahaba.

Turning to politics, Morgan became a presidential elector on the Democratic ticket in 1860, and supported John C. Breckinridge. He was delegate from Dallas County to the State Convention of 1861, which passed the ordinance of secession.

Civil War[]

With Alabama's vote to leave the Union, at the age of 37 Morgan enlisted as a private in the Cahaba Rifles, which volunteered its services in the Confederate Army and was assigned to the 5th Alabama Infantry. He first saw action at the First Battle of Manassas in the summer of 1861. Morgan rose to major and then lieutenant colonel, serving under Col. Robert E. Rodes, a future Confederate general. Morgan resigned in 1862 and returned to Alabama, where in August he recruited a new regiment, the 51st Alabama Partisan Rangers, becoming its colonel. He led it at the Battle of Murfreesborough, operating in cooperation with the cavalry of Nathan Bedford Forrest.

When Rodes was promoted to major general and given a division in the Army of Northern Virginia, Morgan declined an offer to command Rodes's old brigade and instead remained in the Western Theater, leading troops at the Battle of Chickamauga. On November 16, 1863, he was appointed as a brigadier general of cavalry and participated in the Knoxville Campaign. His brigade consisted of the 1st, 3rd, 4th (Russell's), 9th, and 51st Alabama Cavalry regiments.

His men were routed and dispersed by Federal cavalry on January 27, 1864. He was reassigned to a new command and fought in the Atlanta Campaign. Subsequently, his men harassed William T. Sherman's troops during the March to the Sea. Later, he was assigned to administrative duty in Demopolis, Alabama. When the Confederacy collapsed and the war ended, Morgan was trying to organize Alabama black troops for home defense.

Postbellum career[]

After the war, Morgan resumed the practice of law in Selma, Alabama. According to insider information, after the death of James H. Clanton in 1872, Morgan allegedly succeeded him as the Grand Dragon of the Ku Klux Klan in Alabama, but other than a personal account, there is no physical or historical evidence of this.[4][5] He was once again presidential elector on the Democratic ticket in 1876 and was elected as a Democrat to the United States Senate in that year, being re-elected in 1882, 1888, 1894, 1900, and 1906, and serving from March 4, 1877, until his death. For much of his tenure, he served as Senator alongside a fellow former Confederate general, Edmund W. Pettus.

Morgan advocated for separating blacks and whites in the U.S. by encouraging the migration of black people out of the U.S. south. Hochschild wrote, "at various times in his long career Morgan also advocated sending them [negroes] to Hawaii, to Cuba, and to the Philippines - which, perhaps because the islands were so far away, he claimed were a "native home of the negro."[6]

Morgan also staunchly worked for the repeal of the Fifteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which was intended to prevent the denial of voting rights based on race.[7] He "introduced and championed several bills to legalize the practice of racist vigilante murder [lynching] as a means of preserving white power in the Deep South."[8]

He was chairman of Committee on Rules (Forty-sixth Congress), the Committee on Foreign Relations (Fifty-third Congress), the (Fifty-sixth and Fifty-seventh Congresses), and the (Fifty-ninth Congress).

Foreign policy[]

Between 1887 and 1907 Morgan played a leading role on the powerful Foreign Relations Committee. He called for a canal linking the Atlantic and Pacific oceans through Nicaragua, enlarging the merchant marine and the Navy, and acquiring Hawaii, Puerto Rico, the Philippines, and Cuba. He expected Latin American and Asian markets would become a new export market for Alabama's cotton, coal, iron, and timber. The canal would make trade with the Pacific much more feasible, and an enlarged military would protect that new trade. By 1905, most of his dreams had become reality, with of course the canal going through Panama instead of Nicaragua.[9]

In 1894, Morgan chaired an investigation, known as the Morgan Report, into the Hawaiian Revolution, which investigation concluded that the U.S. had remained completely neutral in the matter. He authored the introduction to the Morgan Report based on the findings of the investigative committee.

He was a strong supporter of the annexation of the Republic of Hawaii and visited there in 1897 in support of annexation. He believed that the history of the U.S. clearly indicated it was unnecessary to hold a plebiscite in Hawaii as a condition for annexation. He was appointed by President William McKinley in July 1898 to the commission created by the Newlands Resolution to establish government in the Territory of Hawaii. A strong advocate for a Central American canal, Morgan was also a staunch supporter of the Cuban revolutionaries in the 1890s.

Death and legacy[]

Morgan died in Washington, D.C. while still in office. He was buried in Live Oak Cemetery in Selma, Alabama. The remainder of his term was served by John H. Bankhead.

An article by history professor in the April 2004 Alabama Review says:

His congressional speeches and published writings demonstrate the central role that Morgan played in the drama of racial politics on Capitol Hill and in the national press from 1889 to 1891. More importantly, they reveal his leadership in forging the ideology of white supremacy that dominated American race relations from the 1890s to the 1960s. Indeed, Morgan emerged as the most prominent and notorious racist ideologue of his day, a man who, as much as any other individual, set the tone for the coming Jim Crow era.[10]

Memorialization[]

- In 1953, Morgan was elected to membership in the Alabama Hall of Fame.

- John T. Morgan Academy in Selma is named for Morgan. Founded in 1965, the segregation academy originally held classes in Morgan's old house.

- Morgan Hall on the campus of the University of Alabama, which houses the English Department, was named for him. On December 18, 2015, Morgan's portrait was removed from the building,[11] and in 2016 the university was pondering the results of a petition to rename the building for Harper Lee.[12] By June 2020, the Alabama Board of Trustees had finally decided to study the names of buildings on campus and consider changing them.[13] On September 17, 2020, they voted to remove his name from the building.[14]

- A memorial arch on the grounds of the Federal Building / U.S. Courthouse in Selma honors Senators Morgan and Pettus.

- In World War II, the United States liberty ship SS John Morgan was named in his honor.

See also[]

- List of American Civil War generals (Confederate)

- List of United States Congress members who died in office (1900–49)

Notes[]

- ^ "American Slavery, Civil Records". National Archives. August 15, 2016.

- ^ White, Horace; Langer, Elinor (March 23, 2015). "American Imperialism: This Is When It All Began" – via www.thenation.com.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on December 12, 2008. Retrieved November 9, 2008.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ Ku Klux Klan in Alabama during the Reconstruction Era. The Encyclopedia of Alabama

- ^ Davis, Susan Lawrence, Authentic history, Ku Klux Klan, 1865-1877. New York, 1924, p. 45.

- ^ Hochschild, Adam. King Leopold's Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror, and Heroism in Colonial Africa. Mariner Books; 1st Mariner Books Ed edition (October 1999) p79-80

- ^ Democrats and Republicans: In Their Own Words Archived August 12, 2007, at the Wayback Machine A 124 Year History of Major Civil Rights Efforts Based on a Side-by-Side Comparison of the Early Platforms of the Two Major Political Parties "According to prominent Democrat leader A. W. Terrell of Texas, the 15th Amendment was what he called "the political blunder of the century." Democratic U. S. Rep. Bourke Cockran of New York and Democratic U.S. Senator John Tyler Morgan of Alabama agreed with Terrell and were among the Democrats seeking a repeal of the 15th Amendment."

- ^ Holthouse, David (Winter 2008). "Activists Confront Hate in Selma, Ala". Intelligence Report.

- ^ Joseph A. Fry, "John Tyler Morgan's Southern Expansionism," Diplomatic History (1985) 9#4 pp: 329-346.

- ^ Upchurch, Thomas Adams (April 2004). "Senator John Tyler Morgan and the Genesis of Jim Crow Ideology, 1889-1891". Alabama Review. Archived from the original on June 17, 2006.

- ^ Enoch, Ed (December 18, 2015). "Confederate general's portrait replaced in Morgan Hall". Tuscaloosa News. Retrieved July 14, 2020.

- ^ Gauntt, Joshua (February 26, 2016). "UA president responds to petition to rename Morgan Hall after Harper Lee". WBRC. Retrieved July 14, 2020.

- ^ Mapp, Annie (June 8, 2020). "University of Alabama removes 3 Confederate plaques, to review names of all buildings". WBMA. Retrieved July 14, 2020.

- ^ Bolling, Jessa Reid (September 18, 2020). "University of Alabama trustees vote to rename Morgan Hall". The Crimson White. Retrieved October 26, 2020.

References[]

- United States Congress. "John Tyler Morgan (id: M000954)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- Eicher, John H., and David J. Eicher, Civil War High Commands. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2001. ISBN 978-0-8047-3641-1.

- Fry, Joseph A., John Tyler Morgan and the Search for Southern Autonomy, Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1992, ISBN 0-87049-753-7.

- Sifakis, Stewart. Who Was Who in the Civil War. New York: Facts On File, 1988. ISBN 978-0-8160-1055-4.

- Warner, Ezra J. Generals in Gray: Lives of the Confederate Commanders. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1959. ISBN 978-0-8071-0823-9.

- morganreport.org Online images and transcriptions of the entire Morgan Report

- Alabama Hall of Fame bio

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to John Tyler Morgan. |

| Wikisource has the text of a 1905 New International Encyclopedia article about "John Tyler Morgan". |

- 1824 births

- 1907 deaths

- Alabama Democrats

- Alabama Secession Delegates of 1861

- American people of Welsh descent

- American slave owners

- Confederate States Army brigadier generals

- Democratic Party United States senators

- Ku Klux Klan Grand Dragons

- People from Athens, Tennessee

- People of Alabama in the American Civil War

- 1860 United States presidential electors

- 1876 United States presidential electors

- United States senators from Alabama

- American lynching defenders

- Chairmen of the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations

- American white supremacists