Joseph Zack Kornfeder

Joseph Zack | |

|---|---|

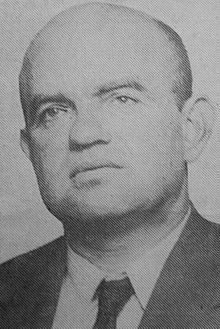

Joseph Zack (1938) | |

| Born | Joseph Zack Kornfeder March 20, 1898 |

| Died | May 1, 1963 (aged 65) Washington, DC |

| Other names | Joe Zack, Joseph Zack Kornfedder, A.C. Griffith, J.P. Collins |

| Years active | 1916–1963 |

Joseph Zack Kornfeder (1898–1963), sometimes surnamed "Kornfedder" in the press,[1] was an Austro-Hungarian-born American who was a founding member and top leader of the Communist Party of America in 1919, Communist Party USA leader, and Comintern representative to South America (1930-1931) before quitting the Party in 1934. After his wife was arrested by the secret police during the Great Terror (1937-1938), Zack became a vehement Anti-Communist and testified before the Dies Committee (1939) and Canwell Committee (1948).[2]

Background[]

Joseph Zack Kornfeder was born on March 20, 1898, in Trencsén, Austria-Hungary (now Trenčín, Slovakia). His parents were from Austria, who raised their son Roman Catholic.

In 1914, Zack traveled to Spain to join the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party.[3] (Knowledge of Spanish would serve later when the Comintern stationed him in Central America.)

In 1915, the Kornfeder family emigrated to the United States in 1915, landing in New York City, where they made a home. Zack took a job as a garment worker and joined the Socialist Party of America within a year.[4]

Career[]

Communist activities[]

In 1919, Zack became a founding member of the Communist Party of America (CPA). In April 1920, he may have left the CPA along with C.E. Ruthenberg to join the rival Communist Labor Party of America (CLP) in establishing the United Communist Party (UCP). Pseudonyms he used include "A.C. Griffith" and "J.P. Collins" during the underground period. Occasionally, he contributed articles to the Party press on trade union-related matters.

In May 1921, Zack was elected a member of the unified Communist Party of America following its formation at a unity convention held at the Overlook Mountain House near Woodstock, New York.[5] He emerged as an outspoken advocate of elimination of the underground form of political organization.

In 1922, Zack went as a delegate to the 1922 Bridgman Convention of the CPA, raided by police on August 22. Zack was arrested in the Justice Department-directed operation and was held for about four months, finally released in early 1923 on $5,000 bail. Zack was involved in the Communist Party's activities among the trade unions, conducted by William Z. Foster's Trade Union Educational League (TUEL). Zack was chosen as the head of TUEL's National Committee of the Needle Trades Section, which was organized November 22, 1922. During the bitter internecine factional struggle which swept the American Communist movement during the 1920s, Zack was a loyal partisan of the faction headed by Foster and James P. Cannon.[2] On April 17, 1923, Zack resigned from the CEC of the CPA, which helped make way for Earl Browder, Robert Minor, and Alfred Wagenknecht, coopted to the 10-member body at that time.[5]

In 1926, Zack married a Russian woman, with whom he had one son. Zack attended the Comintern's International Lenin School (ILS) and sat as an American representative to the Executive Committee of the Communist International (ECCI), where he was made a member of ECCI's Anglo-American Secretariat, charged with Communist affairs in the English-speaking countries.[2] According to Zack, the ILS included courses on Economics, Philosophy, Politics, Trade Union Organization, Party Organization, Military Organization, and the Agrarian Problem.[6]

In 1930, Zack was dispatched as a Comintern Rep to South America, where he remained until the fall of 1931. While Zack was at the Comintern's disposal abroad, his wife and son remained in Moscow. In the fall of 1931, Zack was jailed in Venezuela, only gaining his release through the efforts of the United States Department of State. Home in the United States with his American citizen wife and New York City-born son still in the USSR,[7] Zack was named the Secretary for the Eastern District of the Trade Union Unity League (TUUL), successor to TUEL.[2]

Following his return from Central America, Zack made multiple appeals to CPUSA General Secretary Earl Browder, without success to allow his wife and son to return to the United States.[8] Zack later claimed that Browder coerced him into signing receipts for $1,500 in Comintern funds that were supposed to have been sent to support Zack's efforts in Central America but never sent as a quid pro quo for the return of his wife and son — a promise upon which Browder never delivered.[8]

Break[]

In the Fall of 1934, Zack abruptly quit the CPUSA, ostensibly over the party's departure from the ultra-radicalism of the so-called "Third Period." Zack briefly joined the Workers Party of the United States (WPUS), formed in 1934 by two small political organizations, headed by pacifist A.J. Muste and Trotskyist James P. Cannon, respectively.[2]

Zack then renounced Marxism completely, and founded a new group called the "One Big Union Club."[9]

In 1936, Zack made an appeal to the US State Department in an attempt to persuade the USSR to allow his wife and child out of the country.[10] His effort proved unsuccessful. In 1937, his wife ran afoul of the secret police during the Great Terror. Apparently, she was arrested as a relative of an enemy of the people: she served 18 years in Gulag labor camps, while their son grew up in a special home.[11] The arrest of his wife turned Zack into an opponent of Joseph Stalin and the USSR.[2]

Anti-Communist activities[]

On September 30, 1939, Zack testified before the Dies Committee extensively as a friendly witness. In succeeding years, he established himself as an outspoken anti-communist, addressing conservative gatherings and writing on the dangers of Stalin's dictatorship.[2]

On February 3, 1948, Zack testified to the Canwell Committee of the Washington state legislature.[12] He gave a lengthy account of his career in the communist movement, including details about his activities as a party organizer in the American labor movement and of his break with the Communist International.

On May 1, 1950, in Mosinee, Wisconsin, a local American Legion outpost staged a mock Communist takeover to illustrate what life under Soviet conquest might be like. Benjamin Gitlow, twice CPUSA vice-presidential candidate (1924, 1928), played the role of General Secretary of the "United Soviet States of America", while Zack played the new commissar of the newly renamed town of "Moskva." A Soviet flag flew in front of the American Legion outpost.[13][14]

In May 1951, Gitlow told the Senate's Subversive Activities Control Board that he had "repeatedly discussed" the board with its research director Benjamin Mandel as well as Zack. Gitlow said, "I discussed the conduct of this case. I discussed the attorneys in the case. I discussed the members of the panel."[15]

Personal life and death[]

Zack was married and had at least one child. His wife's imprisonment in the USSR and son's upbringing there caused him to become an anti-communist.

Joseph Zack Kornfeder died age 65 of a heart attack while checking into a Washington, D.C., hotel on May Day, May 1, 1963.[2]

Works[]

- "What Shall We Do in the Unions?" (as "J.P. Collins") (1921)[16]

- "The Line is Correct–To Realize It Organizationally is the Central Problem" (as "J.A. Zack") (1934)[17]

- Communist Front Organizations: Types, Purposes, History and Tactics. Columbus, OH: Ohio Coalition of Patriotic Societies, n.d. [c. 1940].

- Communist Deception in the Churches: An Address before Circuit Riders, Inc., at a National Committee Conference in Cincinnati, Ohio, October 26, 1952. Cincinnati, OH: Circuit Riders, 1952.

- Brainwashing and Senator McCarthy. New York: Alliance, 1954.

- The New Frontier of War. With William Roscoe Kintner. Chicago: Regnery, 1962.

See also[]

- William Z. Foster

- James P. Cannon

- Earl Browder

- Robert Minor

- Alfred Wagenknecht

- Benjamin Gitlow

- Benjamin Mandel

- Socialist Party of America

- Communist Party of America

- Communist Party USA

- Trade Union Educational League (TUEL)

- Trade Union Unity League (TUUL)

- Communist International

- Workers Party of the United States

- anti-Communism

- Dies Committee

- Canwell Committee

References[]

- ^ Croly, Herbert David (28 May 1951). "McCarran's Reds". The New Republic. p. 7. Retrieved 27 April 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h "Joseph Zack Kornfeder Is Dead; Ex-Official of U.S. Reds Was 65; Quit Party in '34 and Testified on It Often--Had Studied Subversion in Moscow". New York Times. 4 May 1963. Retrieved 16 October 2009.

- ^ Branko Lazitch with Milorad M. Drachkovitch, Biographical Dictionary of the Comintern: New, Revised, and Expanded Edition. Stanford, CA: Hoover Institution Press, 1986; pg. 230.

- ^ Harvey Klehr, The Heyday of American Communism: The Depression Decade. New York: Basic Books, 1984; pg. 131.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Communist Party of America Officials," Early American Marxism website. Retrieved October 14, 2009.

- ^ Canwell, et al., First Report, Un-American Activities in Washington State, 1948, pp. 461-462.

- ^ Albert F. Canwell, et al., First Report, Un-American Activities in Washington State, 1948. Olympia, WA: Joint Legislative Fact-Finding Committee on Un-American Activities, 1948; pg. 453.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Canwell, et al., First Report, Un-American Activities in Washington State, 1948, pg. 454.

- ^ Max Shachtman, "Footnote for Historians," New International, Vol. 4, No. 12, December 1938. Shachtman refers to it as an "Oehlerite stooge group".

- ^ Max Shachtman, "The Case of Joseph Zack," The Socialist Appeal [New York], vol.3 no. 30 (July 23, 1938).

- ^ Morris Childs, "Last Days in Moscow," August 21, 1958, pp. 2-3 in "FBI SOLO Files - March 1958 to August 1960." Washington, DC: Federal Bureau of Investigation, August 2011; pdf pages 285-286.

- ^ The testimony appears in Albert F. Canwell, et al., First Report, Un-American Activities in Washington State, 1948. Olympia, WA: Joint Legislative Fact-Finding Committee on Un-American Activities, 1948; pp. 446-498.

- ^ "Mosinee in Hands of 'Reds' After a Make Believe Coup", Milwaukee Journal, May 1, 1950

- ^ "Mayor, Pastor Die at Mosinee", Milwaukee Journal, May 8, 1950, p3; "D-Day in Mosinee" Archived 2014-10-16 at the Wayback Machine, by Carl Weinberg, OAH Magazine of History (October 2010)

- ^ Croly, Herbert David (28 May 1951). "McCarran's Reds". The New Republic. p. 7. Retrieved 27 April 2019.

- ^ Collins, J.P. (September 1921). "What Shall We Do in the Unions?" (PDF). The Communist. Unified CPA: 20–23. Retrieved 13 May 2020.

- ^ Zack, J.A. (April 1934). "The Line is Correct–To Realize It Organizationally is the Central Problem" (PDF). The Communist. Unified CPA: 356–362. Retrieved 13 May 2020.

External links[]

- Max Shachtman, "The Case of Joseph Zack," The Socialist Appeal [New York], vol. 3 no. 30 (July 23, 1938).

- 1898 births

- 1963 deaths

- People from Trenčín

- 20th-century Austrian people

- 20th-century Hungarian people

- American Comintern people

- Members of the Socialist Party of America

- Members of the Communist Party USA

- Members of the Workers Party of the United States

- American Roman Catholics

- Austrian Roman Catholics

- Austrian communists

- American communists

- Hungarian Roman Catholics

- Hungarian-German people

- Austrian people of Hungarian descent

- Austrian expatriates in the United States

- American people of Austrian descent

- Austro-Hungarian emigrants to the United States

- International Lenin School alumni