Julius Erving

Erving in 2016 | |

| Personal information | |

|---|---|

| Born | February 22, 1950 East Meadow, New York |

| Nationality | American |

| Listed height | 6 ft 7 in (2.01 m) |

| Listed weight | 210 lb (95 kg) |

| Career information | |

| High school | Roosevelt (Roosevelt, New York) |

| College | UMass (1969–1971) |

| NBA draft | 1972 / Round: 1 / Pick: 12th overall |

| Selected by the Milwaukee Bucks | |

| Playing career | 1971–1987 |

| Position | Small forward |

| Number | 32, 6 |

| Career history | |

| 1971–1973 | Virginia Squires |

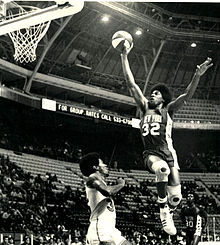

| 1973–1976 | New York Nets |

| 1976–1987 | Philadelphia 76ers |

| Career highlights and awards | |

| |

| Career ABA and NBA statistics | |

| Points | 30,026 (24.2 ppg) |

| Rebounds | 10,525 (8.5 rpg) |

| Assists | 5,176 (4.2 apg) |

| Stats | |

| Stats at Basketball-Reference.com | |

| Basketball Hall of Fame as player | |

| College Basketball Hall of Fame Inducted in 2006 | |

Julius Winfield Erving II (born February 22, 1950), commonly known by the nickname Dr. J, is an American former professional basketball player. Regarded as one of the most influential basketball players of all time,[1][2][3] Erving helped legitimize the American Basketball Association (ABA)[4] and was the best-known player in that league when it merged into the National Basketball Association (NBA) after the 1975–76 season.

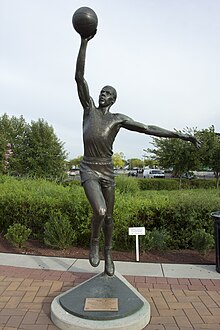

Erving won three championships, four Most Valuable Player Awards, and three scoring titles with the ABA's Virginia Squires and New York Nets (now the NBA's Brooklyn Nets) and the NBA's Philadelphia 76ers. During his 16 seasons as a player, none of his teams ever missed the postseason. He is the eighth-highest scorer in ABA/NBA history with 30,026 points (NBA and ABA combined). He was well known for slam dunking from the free-throw line in slam dunk contests and was the only player voted Most Valuable Player in both the ABA and the NBA. The basketball slang of being posterized was first coined to describe his moves.

Erving was inducted in 1993 into the Basketball Hall of Fame and was also named to the NBA's 50th Anniversary All-Time team. In 1994, Erving was named by Sports Illustrated as one of the 40 most important athletes of all time. In 2004, he was inducted into the Nassau County Sports Hall of Fame.

Many consider him one of the most talented players in the history of the NBA; he is widely acknowledged as one of the game's best dunkers. While Connie Hawkins, "Jumping" Johnny Green, Elgin Baylor, Jim Pollard, and Gus Johnson performed spectacular dunks before Erving's time, Erving brought the practice into the mainstream.[5] His signature dunk was the "slam" dunk, since incorporated into the vernacular and basic skill set of the game in the same manner as the "crossover" dribble and the "no look" pass. Before Erving, dunking was a practice most commonly used by the big men (usually standing close to the hoop) to show their brutal strength which was seen as style over substance, even unsportsmanlike, by many purists of the game.[6] However, the way Erving utilized the dunk more as a high-percentage shot made at the end of maneuvers generally starting well away from the basket and not necessarily a "show of force" helped to make the shot an acceptable tactic, especially in trying to avoid a blocked shot.[7] Although the slam dunk is still widely used as a show of power, a method of intimidation, and a way to fire up a team (and spectators), Erving demonstrated that there can be great artistry and almost balletic style to slamming the ball into the hoop, particularly after a launch several feet from that target.[8]

Early life[]

Erving was born February 22, 1950, in East Meadow, New York,[9][10][11][12][13] and raised from the age of 13 in Roosevelt, New York. Prior to that, he lived in nearby Hempstead.

He attended Roosevelt High School and played for its basketball team. He received the nickname "Doctor" or "Dr. J" from a high school friend named Leon Saunders.[14] He explains,

I have a buddy—his name is Leon Saunders—and he lives in Atlanta, and I started calling him "the professor", and he started calling me "the doctor". So it was just between us...we were buddies, we had our nicknames and we would roll with the nicknames. ...And that's where it came from.

Erving recalled, "[L]ater on, in the Rucker Park league in Harlem, when people started calling me 'Black Moses' and 'Houdini', I told them if they wanted to call me anything, call me 'Doctor,'"[15] Over time, the nickname evolved into "Dr. Julius," and finally "Dr. J."[16]

College career[]

Erving enrolled at the University of Massachusetts in 1968. In two varsity college basketball seasons, he averaged 26.3 points[17] and 20.2 rebounds per game, becoming one of only six players[18] to average more than 20 points and 20 rebounds per game in NCAA Men's Basketball.[19] He then sought “hardship” entry into professional basketball in 1971.

Fifteen years later Erving fulfilled a promise he had made to his mother by earning a bachelor's degree in creative leadership and administration from the school through the University Without Walls program.[20][21] Erving also holds an honorary doctorate from the school.[20]

Professional career[]

Virginia Squires (ABA)[]

Although NBA rules at the time did not allow teams to draft players who were less than four years removed from high school, the ABA instituted a “hardship” rule that would allow players to leave college early.[22] Erving took advantage of the rule change and left Massachusetts after his junior year to sign a four-year contract worth $500,000 spread over seven years with the Virginia Squires.[23][24]

Erving quickly established himself as a force and gained a reputation for hard and ruthless dunking. He scored 27.3 points per game as a rookie, was selected to the All-ABA Second Team, made the ABA All-Rookie Team, led the ABA in offensive rebounds, and finished second to Artis Gilmore for the ABA Rookie of the Year Award. He led the Squires into the Eastern Division Finals, where they lost to the Rick Barry-led New York Nets in seven games. The Nets would eventually go to the finals, losing to the star-studded Indiana Pacers team.[25]

Contract dispute[]

Under NBA rules, he became eligible for the 1972 NBA draft and the Milwaukee Bucks picked him in the first round (12th overall). This move would have brought him together with Oscar Robertson and Kareem Abdul-Jabbar. However, prior to the draft, he signed a contract with the NBA Atlanta Hawks worth more than $1 million with a $250,000 bonus.[26] The signing with the Hawks came after a dispute with the Squires where he demanded a renegotiation of the terms.[24] He discovered that his agent at the time, Steve Arnold, was employed by the Squires and convinced him to sign a below-market contract.[27]

This created a dispute between three teams in two leagues. The Bucks asserted their rights to Erving via the draft, while the Squires went to court to force him to honor his contract. He joined Pete Maravich at the Hawks' training camp, as they prepared for the upcoming season. He played two exhibition games with the Hawks until NBA Commissioner J. Walter Kennedy ruled that the Bucks owned Erving's rights via the draft. Kennedy fined the Hawks $25,000 per game in violation of his ruling. Atlanta appealed Kennedy's decision to the league owners, who also supported the Bucks’ position.[28] While waiting for the owners’ decision, Erving played in one more preseason game, earning the Hawks another fine. Erving enjoyed his brief time with Atlanta, and he would later duplicate with George Gervin his after-practice playing with Maravich.[29]

On October 2, Judge Edward Neaher issued an injunction that prohibited him from playing for any team other than the Squires. The judge then sent the case to arbitration because of an arbitration clause in Erving’s contract with Virginia.[29] He agreed to report to the Squires while his appeal of the injunction made its way through the court.[30]

Back in the ABA, his game flourished, and he achieved a career-best 31.9 points per game in the 1972–1973 season. The following year, the cash-strapped Squires sold his contract to the New York Nets.[31]

New York Nets (ABA)[]

The Squires, like most ABA teams, were on rather shaky financial ground. The cash-strapped team sent Erving to the Nets in a complex deal that kept him in the ABA. Erving signed an eight-year deal worth a reported $350,000 per year. The Squires received $750,000, George Carter, and the rights to Kermit Washington for Erving and Willie Sojourner. The Nets also sent $425,000 to the Hawks to reimburse the team for its legal fees, fines and the bonus paid to Erving. Finally, Atlanta would receive draft compensation should a merger of the league result in a common draft.[26]

He went on to lead the Nets to their first ABA title in 1973–74, defeating the Utah Stars.[32] Erving established himself as the most important player in the ABA. His spectacular play established the Nets as one of the better teams in the ABA, and brought fans and credibility to the league.[33] The end of the 1975–76 ABA season finally brought the ABA–NBA merger. The Nets and Nuggets had applied for admission to the NBA before the season, in anticipation of the eventual merger that had first been proposed by the two leagues in 1970 but which was delayed for various reasons, including the Oscar Robertson free agency suit (which was not resolved until 1976). The Erving-led Nets defeated the Denver Nuggets in the ABA’s final championship. In the postseason, Erving averaged 34.7 points and was named Most Valuable Player of the playoffs. That season, he finished in the top 10 in the ABA in points per game, rebounds per game, assists per game, steals per game, blocks per game, free throw percentage, free throws made, free throws attempted, three-point field goal percentage and three-point field goals made.[34]

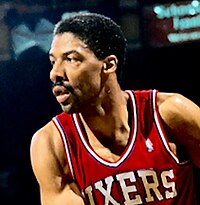

Philadelphia 76ers[]

This section of a biography of a living person needs additional citations for verification. (February 2013) |

The Nets, Nuggets, Indiana Pacers, and San Antonio Spurs joined the NBA for the 1976–77 season. With Erving and Nate Archibald (acquired in a trade with Kansas City), the Nets were poised to pick up right where they left off. However, the New York Knicks upset the Nets' plans when they demanded that the Nets pay them $4.8 million for "invading" the Knicks' NBA territory. Coming on the heels of the fees the Nets had to pay for joining the NBA, owner Roy Boe reneged on a promise to raise Erving's salary. Erving refused to play under these conditions and held out in training camp.[35]

After several teams such as the Milwaukee Bucks, Los Angeles Lakers and Philadelphia 76ers lobbied to obtain him, the Nets offered Erving's contract to the New York Knicks in return for waiving the indemnity, but the Knicks turned it down. This was considered one of the worst decisions in franchise history.[36] The Sixers then decided to offer to buy Erving's contract for $3 million—in addition to paying roughly the Nets same amount as their expansion fee—and Boe had little choice but to accept the $6 million deal.[37] For all intents and purposes, the Nets traded their franchise player for a berth in the NBA. The Erving deal left the Nets in ruin; they promptly crashed to a 22–60 record, the worst in the league.[38] Years later, Boe regretted having to trade Erving to join the NBA, saying, "The merger agreement killed the Nets as an NBA franchise."[39]

Erving quickly became the leader of his new club and led them to an exciting 50-win season. However, playing with other stars-such as former ABA standout George McGinnis, future NBA All-Star Lloyd Free, and aggressive Doug Collins allowed him to focus on playing more team-oriented ball. Despite a smaller role, Erving stayed unselfish. The Sixers won the Atlantic Division and were the top drawing team in the NBA. They defeated the defending champions, the Boston Celtics, to win the Eastern Conference. Erving took them into the NBA Finals against the Portland Trail Blazers of Bill Walton. After the Sixers took a 2–0 lead, however, the Blazers ran off four straight victories after the famous brawl between Maurice Lucas and Darryl Dawkins which ignited the Blazers' team.[40]

However, Erving enjoyed success off the court, becoming one of the first basketball players to endorse many products and to have a shoe marketed under his name. He also starred in the 1979 basketball comedy film, The Fish That Saved Pittsburgh.

In the following years, Erving coped with a team that was not yet playing at his level. It took a few years for the Sixers franchise to build around Erving. Eventually, coach Billy Cunningham and top-level players like Maurice Cheeks, Andrew Toney, and Bobby Jones were added to the mix and the franchise was very successful.

The Sixers were still eliminated twice in the Eastern Conference Finals. In 1979, Larry Bird entered the league, reviving the Boston Celtics and the storied Celtics–76ers rivalry; these two teams faced each other in the Eastern Conference Finals in 1980, 1981, 1982, and 1985. The Bird vs. Erving matchup became arguably the top personal rivalry in the sport (along with Bird vs. Magic Johnson), inspiring the early Electronic Arts video game One on One: Dr. J vs. Larry Bird.

In 1980, the 76ers prevailed over the Celtics to advance to the NBA Finals against the Los Angeles Lakers. There, Erving executed the legendary "Baseline Move", a behind-the-board reverse layup. However, the Lakers won 4–2 with superb play from, among others, Magic Johnson.

Erving again was among the league's best players in the 1980–1981 and 1981–1982 seasons, although more disappointment came as the Sixers stumbled twice in the playoffs: in 1981, the Celtics eliminated them in seven games in the 1981 Eastern Finals after Philadelphia had a 3–1 series lead, but lost both Game 5 and Game 6 by 2 points and the deciding Game 7 by 1; and in 1982, the Sixers managed to beat the defending champion Celtics in seven games in the 1982 Eastern Finals but lost the NBA Finals to the Los Angeles Lakers in six games. Despite these defeats, Erving was named the NBA MVP in 1981 and was again voted to the 1982 All-NBA First Team.[41]

Finally, for the 1982–83 season, the Sixers obtained the missing element to combat their weakness at their center position, Moses Malone. Armed with one of the most formidable and unstoppable center-forward combinations of all time, the Sixers dominated the whole season, prompting Malone to make the famous playoff prediction of "fo-fo-fo (four-four-four)" in anticipation of the 76ers sweeping the three rounds of the playoffs en route to an NBA title.[42] In fact, the Sixers went four-five-four, losing one game to the Milwaukee Bucks in the conference finals, then sweeping the Lakers to win the NBA title.

Erving maintained his all-star caliber of play into his twilight years, averaging 22.4, 20.0, 18.1, and 16.8 points per game in his final seasons.[43] In 1986, he announced that he would retire after the season, causing every game he played to be sold out with adoring fans.[citation needed] That final season saw opposing teams pay tribute to Erving in the last game Erving would play in their arenas, including in cities such as Boston and Los Angeles, his perennial rivals in the playoffs.[citation needed]

Career summary[]

This section of a biography of a living person does not include any references or sources. (February 2013) |

Erving retired in 1987 at the age of 37. "A young Julius Erving was like Thomas Edison, he was always inventing something new every night", Johnny Kerr told ABA historian Terry Pluto. He is also one of the few players in modern basketball to have his number retired by two franchises: the Brooklyn Nets (formerly the New York Nets and New Jersey Nets) have retired his No. 32 jersey, and the Philadelphia 76ers his No. 6 jersey. He was an excellent all around player who was also an underrated defender. In his ABA days, he would guard the best forward, whether small forward or power forward, for over 40 minutes a game, and simultaneously be the best passer, ball handler, and clutch scorer every night. Many of Erving's acrobatic highlight feats and clutch moments were unknown because of the ABA's scant television coverage. He is considered by many as the greatest dunker of all time.

In his ABA and NBA careers combined, he scored more than 30,000 points. In 1993, Erving was elected to the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame. When he retired, Erving ranked in the top 5 in scoring (third), field goals made (third), field goals attempted (fifth) and steals (first). On the combined NBA/ABA scoring list, Erving ranked third with 30,026 points. As of 2019, Erving ranks eighth on the list, behind only Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Karl Malone, LeBron James, Kobe Bryant, Michael Jordan, Dirk Nowitzki, and Wilt Chamberlain.

Feats[]

1976 ABA Slam Dunk Contest[]

This section of a biography of a living person needs additional citations for verification. (February 2013) |

Erving in this memorable contest faced George "The Iceman" Gervin, All-Star and former teammate Larry "Special K" Kenon, MVP Artis "The A-Train" Gilmore, and David "The Skywalker" Thompson. Erving started by dunking two balls in the hoop. Then, he released a move that brought the slam dunk contest to the national consciousness. He went all the way to the end of the court and ran to release a free throw line dunk. Although dunking from the foul line had been done by other players (Jim Pollard and Wilt Chamberlain in the 1950s, for example), Erving introduced the dunk jumping off the foul line to a wide audience, when he demonstrated the feat in the 1976 ABA All-Star Game Dunking Contest.

Dunk over Bill Walton[]

This event transpired during game 6 of the 1977 NBA Finals. After Portland scored a basket, Erving immediately ran the length of the court with the entire Blazers team defending him. He performed a crossover to blow by multiple defenders and seemingly glided to the hoop with ease. With UCLA defensive legend Bill Walton waiting in the post, Erving threw down a vicious slam dunk over Walton's outstretched arms. This dunk is considered by many to be one of the strongest dunks ever attempted,[citation needed] considering he ran full court with all five defenders running with him. This move was one of the highlights of his arrival to a more television-exposed NBA.

The Baseline Move[]

One of his most memorable plays occurred during the 1980 NBA Finals, when he executed a seemingly impossible finger-roll behind the backboard.[44][45] He drove past Lakers forward Mark Landsberger on the right baseline and went in for a layup. Then 7′2″ center Kareem Abdul-Jabbar crossed his way, blocking the route to the basket and forcing him outwards. In mid-air, it was apparent that Erving would land behind the backboard. But somehow he managed to reach over and score on a right-handed layup despite the fact that his whole body, including his left shoulder, was already behind the hoop. This move, along with his free-throw line dunk, has become one of the signature events of his career. It was called by Sports Illustrated, "The, No Way, even for Dr J, Flying Reverse Lay-up". Dr J called it "just another move".

Rock The Baby over Michael Cooper[]

Another of Erving's most memorable plays came in the final moments of a regular-season game against the Los Angeles Lakers in 1983. After Sixers point guard Maurice Cheeks deflected a pass by Lakers forward James Worthy, Erving picked up the ball and charged down the court's left side, with one defender to beat—the Lakers' top defender Michael Cooper. As he came inside of the 3-point line, he cupped the ball into his wrist and forearm, rocking the ball back and forth before taking off for what Lakers radio broadcaster Chick Hearn best described as a "Rock The Baby" slam dunk: he slung the ball around behind his head and dunked over a ducking Cooper. This dunk is generally regarded as one of the greatest dunks of all time.[46]

Post-basketball career[]

Erving earned his bachelor's degree in 1986 through the University Without Walls at the University of Massachusetts Amherst.[47][48][49] After his basketball career ended, he became a businessman, obtaining ownership of a Coca-Cola bottling plant in Philadelphia and doing work as a television analyst. In 1997, he joined the front office of the Orlando Magic as Vice President of RDV Sports and Executive Vice President.[50]

Erving and former NFL running back Joe Washington fielded a NASCAR Busch Series team from 1998 to 2000,[51] becoming the first ever NASCAR racing team at any level owned completely by minorities. The team had secure sponsorship from Dr Pepper for most of its existence. Erving, a racing fan himself, stated that his foray into NASCAR was an attempt to raise interest in NASCAR among African-Americans.[citation needed]

He has also served on the Board of Directors of Converse (prior to their 2001 bankruptcy), Darden Restaurants, Saks Incorporated and The Sports Authority. As of 2009, Erving was the owner of The Celebrity Golf Club International outside of Atlanta, but the club was forced to file for bankruptcy soon after.[52] He was ranked by ESPN as one of the greatest athletes of the 20th Century.

Erving made a cameo appearance as himself in "Lice", the tenth episode of the ninth season of the comedy series The Office (2013).[53]

Erving made a cameo appearance in the sitcom "Hanging with Mr. Cooper" in 1995.[54] Erving also made a cameo appearance in the movie "Philadelphia" starring Tom Hanks and Denzel Washington in 1993.

ABA and NBA career statistics[]

| GP | Games played | GS | Games started | MPG | Minutes per game |

| FG% | Field goal percentage | 3P% | 3-point field goal percentage | FT% | Free throw percentage |

| RPG | Rebounds per game | APG | Assists per game | SPG | Steals per game |

| BPG | Blocks per game | PPG | Points per game | Bold | Career high |

| † | Won an NBA championship | * | Led the league |

| † | Denotes seasons in which Erving's team won an ABA championship |

Regular season[]

| Year | Team | GP | GS | MPG | FG% | 3P% | FT% | RPG | APG | SPG | BPG | PPG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1971–72 | Virginia (ABA) | 84 | - | 41.8 | .498 | .188 | .745 | 15.7 | 4.0 | - | - | 27.3* |

| 1972–73 | Virginia (ABA) | 71 | - | 42.2* | .496 | .208 | .776 | 12.2 | 4.2 | 2.5 | 1.8 | 31.9* |

| 1973–74† | New York (ABA) | 84 | - | 40.5 | .512 | .395 | .766 | 10.7 | 5.2 | 2.3 | 2.4 | 27.4 |

| 1974–75 | New York (ABA) | 84* | - | 40.5 | .506 | .333 | .799 | 10.9 | 5.5 | 2.2 | 1.9 | 27.9 |

| 1975–76† | New York (ABA) | 84 | - | 38.6 | .507 | .330 | .801 | 11.0 | 5.0 | 2.5 | 1.9 | 29.3 |

| 1976–77 | Philadelphia | 82 | - | 35.9 | .499 | - | .777 | 8.5 | 3.7 | 1.9 | 1.4 | 21.6 |

| 1977–78 | Philadelphia | 74 | - | 32.8 | .502 | - | .845 | 6.5 | 3.8 | 1.8 | 1.3 | 20.6 |

| 1978–79 | Philadelphia | 78 | - | 35.9 | .491 | - | .745 | 7.2 | 4.6 | 1.7 | 1.3 | 23.1 |

| 1979–80 | Philadelphia | 78 | - | 36.1 | .519 | .200 | .787 | 7.4 | 4.6 | 2.2 | 1.8 | 26.9 |

| 1980–81 | Philadelphia | 82 | - | 35.0 | .521 | .222 | .787 | 8.0 | 4.4 | 2.1 | 1.8 | 24.6 |

| 1981–82 | Philadelphia | 81 | 81 | 34.4 | .546 | .273 | .763 | 6.9 | 3.9 | 2.0 | 1.7 | 24.4 |

| 1982–83† | Philadelphia | 72 | 72 | 33.6 | .517 | .286 | .759 | 6.8 | 3.7 | 1.6 | 1.8 | 21.4 |

| 1983–84 | Philadelphia | 77 | 77 | 34.8 | .512 | .333 | .754 | 6.9 | 4.0 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 22.4 |

| 1984–85 | Philadelphia | 78 | 78 | 32.5 | .494 | .214 | .765 | 5.3 | 3.0 | 1.7 | 1.4 | 20.0 |

| 1985–86 | Philadelphia | 74 | 74 | 33.4 | .480 | .281 | .785 | 5.0 | 3.4 | 1.5 | 1.1 | 18.1 |

| 1986–87 | Philadelphia | 60 | 60 | 32.0 | .471 | .264 | .813 | 4.4 | 3.2 | 1.3 | 1.6 | 16.8 |

| Career | 1243 | 442 | 36.4 | .506 | .298 | .777 | 8.5 | 4.2 | 2.0 | 1.7 | 24.2 | |

Playoffs[]

| Year | Team | GP | GS | MPG | FG% | 3P% | FT% | RPG | APG | SPG | BPG | PPG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1972 | Virginia (ABA) | 11 | - | 45.8 | .518 | .250 | .835 | 20.4* | 6.5 | - | - | 33.3* |

| 1973 | Virginia (ABA) | 5 | - | 43.8* | .527 | .000 | .750 | 9.0 | 3.2 | - | - | 29.6* |

| 1974† | New York (ABA) | 14 | - | 41.4 | .528 | .455 | .741 | 9.6 | 4.8 | 1.6 | 1.4 | 27.9* |

| 1975 | New York (ABA) | 5 | - | 42.2 | .455 | .000 | .844 | 9.8 | 5.6 | 1.0 | 1.8 | 27.4 |

| 1976† | New York (ABA) | 13* | - | 42.4* | .533 | .286 | .804 | 12.6 | 4.9 | 1.9 | 2.0 | 34.7* |

| 1977 | Philadelphia | 19* | - | 39.9 | .523 | - | .821 | 6.4 | 4.5 | 2.2 | 1.2 | 27.3 |

| 1978 | Philadelphia | 10 | - | 35.8 | .489 | - | .750 | 9.7 | 4.0 | 1.5 | 1.8 | 21.8 |

| 1979 | Philadelphia | 9 | - | 41.3 | .517 | - | .761 | 7.8 | 5.9 | 2.0 | 1.9 | 25.4 |

| 1980 | Philadelphia | 18* | - | 38.6 | .488 | .222 | .794 | 7.6 | 4.4 | 2.0 | 2.1 | 24.4 |

| 1981 | Philadelphia | 16 | - | 37.0 | .475 | .000 | .757 | 7.1 | 3.4 | 1.4 | 2.6 | 22.9 |

| 1982 | Philadelphia | 21* | - | 37.1 | .519 | .167 | .752 | 7.4 | 4.7 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 22.0 |

| 1983† | Philadelphia | 13 | - | 37.9 | .450 | .000 | .721 | 7.6 | 3.4 | 1.2 | 2.1 | 18.4 |

| 1984 | Philadelphia | 5 | - | 38.8 | .474 | .000 | .864 | 6.4 | 5.0 | 1.6 | 1.2 | 18.2 |

| 1985 | Philadelphia | 13 | 13 | 33.4 | .449 | .000 | .857 | 5.6 | 3.7 | 1.9 | 0.8 | 17.1 |

| 1986 | Philadelphia | 12 | 12 | 36.1 | .450 | .182 | .738 | 5.8 | 4.2 | 0.9 | 1.3 | 17.7 |

| 1987 | Philadelphia | 5 | 5 | 36.0 | .415 | .333 | .840 | 5.0 | 3.4 | 1.4 | 1.2 | 18.2 |

| Career | 189 | 30 | 38.9 | .496 | .224 | .784 | 8.5 | 4.4 | 1.7 | 1.7 | 24.2 | |

Personal life[]

Erving is a Christian. Erving has spoken about his faith, saying, "After searching for the meaning of life for over ten years, I found the meaning in Jesus Christ."[55]

Erving was first called "Dr. J" by his friend and teammate on the Nets and Squires, Willie Sojourner.[56]

In 1988, Erving received the Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement.[57]

Erving was married to Turquoise Erving from 1972 until 2003. Together they had four children. In 2000, their 19-year-old son Cory went missing for weeks, until he was found drowned after driving his vehicle into a pond. Erving has called this the worst day of his life.[58]

In 1979, Erving began an affair with sportswriter Samantha Stevenson, resulting in the 1980 birth of Alexandra Stevenson, who would become a WTA professional tennis player. Although Erving's fatherhood of Alexandra Stevenson was known privately to the families involved, it did not become public knowledge until Stevenson reached the semifinals at Wimbledon in 1999, the first year she qualified to play in the tournament. Erving had provided financial support for Stevenson over the years, but had not otherwise been part of her life. The public disclosure of their relationship did not initially lead to contact between father and daughter. However, Stevenson contacted Erving in 2008 and they finally initiated a further relationship.[59] In 2009 Erving attended the Family Circle Cup tennis tournament to see Stevenson play, marking the first time he had attended one of her matches.[60]

In 2003, he fathered a second child outside of his marriage, Justin Kangas, with a woman named Dorýs Madden. Julius and Turquoise Erving were subsequently divorced and Erving continued his relationship with Madden, with whom he had three more children, Jules Erving and two others, thus four in total.[59] They married in 2008.[61]

See also[]

- List of National Basketball Association career steals leaders

- List of National Basketball Association career blocks leaders

- List of National Basketball Association career playoff scoring leaders

- List of National Basketball Association career playoff steals leaders

- List of National Basketball Association career playoff blocks leaders

- List of National Basketball Association career playoff turnovers leaders

References[]

- ^ "The 25 Best Players in ABA History". Complex. February 23, 2014. Retrieved March 24, 2021.

- ^ "25 Greatest Players in ABA History". FanSided. March 18, 2016. Retrieved March 24, 2021.

- ^ "Legends profile: Julius Erving". NBA.com. Retrieved March 24, 2021.

- ^ "Julius Erving Biography and Interview". www.achievement.org. American Academy of Achievement.

- ^ For Some N.B.A. Players, There’s No Such Thing as a Slam Dunk, The New York Times

- ^ J. Ted Carter. (September 1, 1971). "Patterned fast-break basketball". Retrieved July 20, 2015.

- ^ Golliver, Ben. (June 11, 2013). "Video: Julius 'Dr. J' Erving can still dunk a basketball at age 63". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved July 20, 2015.

- ^ Carson, Dan. (June 11, 2013). "This Video of Julius Erving Dunking at the Age of 63 Is Life-Changing". Bleacher Report. Retrieved July 20, 2015.

- ^ Harris, Robert L., Jr.; Terborg-Penn, Rosalyn (September 5, 2008). The Columbia Guide to African American History Since 1939. ISBN 9780231138116. Retrieved March 22, 2011.

- ^ Olson, James Stuart (1999). Historical dictionary of the 1970s. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 149. ISBN 9780313305436. Retrieved March 22, 2011.

julius erving born east meadow.

- ^ Salzman, Jack (September 17, 2008). Encyclopedia of African-American Culture and History. ISBN 9780028973647. Retrieved March 22, 2011.

- ^ "Dr. J operated above the rest". ESPN. Retrieved March 22, 2011.

- ^ "Julius Erving Summary". NBA.com. Retrieved March 22, 2011.

- ^ "Dr. J' Julius Erving explains his nickname exclusively to Class Act Sports". Archived from the original on March 29, 2012. Retrieved May 21, 2012.

- ^ Vincent Mallozzi. Doc: The Rise and Rise of Julius Erving. 60-61.

- ^ Bill Rhoden. "The Incredible Dr. J". Ebony. March 1975. 47.

- ^ "Julius Erving". umasshoops.com.

- ^ "Spencer Haywood College Stats — College Basketball". Sports-Reference.com.

- ^ "NCAA Basketball Records" (PDF). Archived from the original on July 3, 2007. Retrieved October 11, 2006.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- ^ Jump up to: a b Patricia Sullivan, UMass Magazine, http://viewer.zmags.com/publication/c8aaed6f#/c8aaed6f/22

- ^ Phil Jasner, Philadelphia Daily News, The Graduate On Sunday, Julius Erving Gets His College Degree, May 23, 1986. Retrieved November 17, 2013.

- ^ "The Evolution of Younger Athletes in Professional Sports". Washington Post, archived at LATimes.com. September 22, 1990.

- ^ Julius Erving Biography, ESPN.com Retrieved November 17, 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Erving of Squires May Switch to the N.B.A." The New York Times. February 27, 1972.

- ^ "1971-72 New York Nets Roster and Stats". basketball-reference.com. Retrieved July 20, 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Nets' Erving Deal Costs $4‐Million". The New York Times. August 2, 1973.

- ^ "NBA.com: Julius Erving Bio". NBA Media Ventures, LLC. Retrieved December 16, 2008.

- ^ "Erving Awarded to Bucks By N.B.A." The New York Times. September 21, 1972.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "The Doctor is Out". NBA.com. Retrieved July 20, 2018.

- ^ "Erving Rejoins Squires Tonight". The New York Times. October 20, 1972.

- ^ Frederick J. Day. (2004). "Clubhouse Lawyer: Law in the World of Sports". Retrieved July 20, 2015.

- ^ basketball-reference.com "1973-74 New York Nets Roster and Stats" – Accessed September 16, 2013

- ^ NBA TV – Greatest NBA Rivalries. (Available on Video on YouTube), Accessed September 16, 2013.

- ^ Julius Erving. basketball-reference.com

- ^ Pluto, Terry, Loose Balls: The Short, Wild Life of the American Basketball Association (Simon & Schuster, 1990), ISBN 978-1-4165-4061-8, pp. 433–434

- ^ Simmons, Bill (2009). The Book of Basketball: The NBA According to the Sports Guy. ESPN Books. ISBN 978-0-345-51176-8

- ^ Watanabe, Ben. (August 7, 2012). "Julius Erving Wore No. 6 With Sixers to Be Like Bill Russell, ‘One of My Heroes’ (Video)". Retrieved July 20, 2015.

- ^ "1976-77 NBA Season Summary". basketball-reference.com. Retrieved July 20, 2015.

- ^ Pluto, Terry, Loose Balls: The Short, Wild Life of the American Basketball Association (Simon & Schuster, 1990), ISBN 978-1-4165-4061-8, pp.433–434

- ^ "Walton, Lucas Ignite 'Blazermania'". Retrieved July 20, 2015.

- ^ 1982 NBA Awards

- ^ Original Old School: First and Foremost SLAM 72: From high school to the pros, Moses Malone was on another level, by Alan Paul published in SLAM, June 2003

- ^ https://www.basketball-reference.com/players/e/ervinju01.html

- ^ 1980: Dr.J Baseline Scoop on YouTube

- ^ "Doctor's Shot Stuns Lakers". NBA.com. Retrieved March 22, 2011.

- ^ Dr J's famous "Rock The Baby Dunk" Against Lakers on YouTube

- ^ UMASS Alumni Association, http://www.umassalumni.com/membership/notable.html

- ^ NBA, Legends in Business Q&A, http://www.nba.com/careers/legends__erving.html

- ^ Business West, Breaking Down the Barriers, December 1, 2004, http://www.allbusiness.com/specialty-businesses/1074099-1.html

- ^ "http://www.nba.com/history/legends/julius-erving/index.html"

- ^ Pockrass, Bob (January 31, 2014). "NFL and NASCAR: Former NFL stars who dabbled in stock-car racing". Sporting News. Archived from the original on May 22, 2013. Retrieved March 2, 2014.

- ^ "http://www.ajc.com/news/sports/dr-js-golf-course-in-foreclosure/nQdpQ/"

- ^ Trammell, Mark (January 11, 2013). "The Office Season 9 Review 'Lice'". TV Equals. Daemons Media Inc. Retrieved January 11, 2013.

- ^ https://www.imdb.com/name/nm0259973/

- ^ Dr. J.: What Keeps Julius Erving Going?, Wheaton, Illinois: Good News Publishers, 1985, p. 2

- ^ "SOJOURNER DEAD AT 58". nypost.com. October 23, 2005.

- ^ "Golden Plate Awardees of the American Academy of Achievement". www.achievement.org. American Academy of Achievement.

- ^ CBC Sports (August 2, 2000). "Son of Julius Erving died of accidental drowning". CBC Sports. Retrieved March 22, 2011.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Friend, Tom (December 15, 1980). "Reaching Out". ESPN. Retrieved March 22, 2011.

- ^ "Stevenson loses in first round". Associated Press. April 14, 2009.

- ^ Jackson, Patty. (January 2, 2009). "what's the 411?", Philadelphia Tribune, Page 11-E

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Julius Erving. |

- 1950 births

- Living people

- African-American sports announcers

- African-American sports journalists

- African-American basketball players

- African-American Christians

- All-American college men's basketball players

- American men's basketball players

- Basketball coaches from New York (state)

- Basketball players from New York (state)

- Big3 coaches

- Milwaukee Bucks draft picks

- Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame inductees

- National Basketball Association All-Stars

- National Basketball Association broadcasters

- National Basketball Association players with retired numbers

- New York Nets players

- Orlando Magic executives

- People from East Meadow, New York

- People from Roosevelt, New York

- Philadelphia 76ers players

- Small forwards

- Sportspeople from Nassau County, New York

- UMass Minutemen basketball players

- Virginia Squires players