Juno (spacecraft)

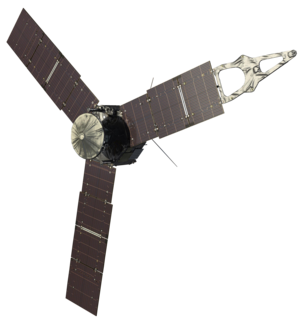

Artist's rendering of the Juno spacecraft | |||

| Names | New Frontiers 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mission type | Jupiter orbiter | ||

| Operator | NASA / JPL | ||

| COSPAR ID | 2011-040A | ||

| SATCAT no. | 37773 | ||

| Website | |||

| Mission duration | Planned: 7 years Elapsed: 10 years, 25 days Cruise: 4 years, 10 months, 29 days Science phase: 4 years (extended until September 2025) | ||

| Spacecraft properties | |||

| Manufacturer | Lockheed Martin | ||

| Launch mass | 3,625 kg (7,992 lb) [1] | ||

| Dry mass | 1,593 kg (3,512 lb) [2] | ||

| Dimensions | 20.1 × 4.6 m (66 × 15 ft) [2] | ||

| Power | 14 kW at Earth,[2] 435 W at Jupiter [1] 2 × 55-ampere hour lithium-ion batteries[2] | ||

| Start of mission | |||

| Launch date | 5 August 2011, 16:25:00 UTC | ||

| Rocket | Atlas V 551 (AV-029) | ||

| Launch site | Cape Canaveral, SLC-41 | ||

| Contractor | United Launch Alliance | ||

| Flyby of Earth | |||

| Closest approach | 9 October 2013 | ||

| Distance | 559 km (347 mi) | ||

| Jupiter orbiter | |||

| Orbital insertion | 5 July 2016, 03:53:00 UTC [3] 5 years, 1 month, 26 days ago | ||

| Orbits | 76 (planned) [4][5] | ||

| Orbital parameters | |||

| Perijove altitude | 4,200 km (2,600 mi) altitude 75,600 km (47,000 mi) radius | ||

| Apojove altitude | 8.1×106 km (5.0×106 mi) | ||

| Inclination | 90° (polar orbit) | ||

| |||

Juno mission patch New Frontiers program | |||

Juno is a NASA space probe orbiting the planet Jupiter. It was built by Lockheed Martin and is operated by NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory. The spacecraft was launched from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station on 5 August 2011 UTC, as part of the New Frontiers program.[6] Juno entered a polar orbit of Jupiter on 5 July 2016 UTC,[4][7] to begin a scientific investigation of the planet.[8] After completing its mission, Juno will be intentionally deorbited into Jupiter's atmosphere.[8]

Juno's mission is to measure Jupiter's composition, gravitational field, magnetic field, and polar magnetosphere. It will also search for clues about how the planet formed, including whether it has a rocky core, the amount of water present within the deep atmosphere, mass distribution, and its deep winds, which can reach speeds up to 620 km/h (390 mph).[9]

Juno is the second spacecraft to orbit Jupiter, after the nuclear powered Galileo orbiter, which orbited from 1995 to 2003.[8] Unlike all earlier spacecraft sent to the outer planets,[8] Juno is powered by solar panels, commonly used by satellites orbiting Earth and working in the inner Solar System, whereas radioisotope thermoelectric generators are commonly used for missions to the outer Solar System and beyond. For Juno, however, the three largest solar panel wings ever deployed on a planetary probe play an integral role in stabilizing the spacecraft as well as generating power.[10]

Naming[]

Juno's name comes from Greek and Roman mythology. The god Jupiter drew a veil of clouds around himself to hide his mischief, and his wife, the goddess Juno, was able to peer through the clouds and reveal Jupiter's true nature.

— NASA [11]

A NASA compilation of mission names and acronyms referred to the mission by the backronym Jupiter Near-polar Orbiter.[12] However the project itself has consistently described it as a name with mythological associations[13] and not an acronym. The spacecraft's current name is in reference to the roman goddess Juno.[11] Juno is sometimes called the New Frontiers 2 as the second mission in the New Frontiers program,[14][15] but is not to be confused with New Horizons 2, a proposed but unselected New Frontiers mission.

Overview[]

Juno · Earth · Mars · Jupiter

Juno was selected on 9 June 2005, as the next New Frontiers mission after New Horizons.[16] The desire for a Jupiter probe was strong in the years prior to this, but there had not been any approved missions.[17][18] The Discovery Program had passed over the somewhat similar but more limited Interior Structure and Internal Dynamical Evolution of Jupiter (INSIDE Jupiter) proposal,[18] and the turn-of-the-century era Europa Orbiter was canceled in 2002.[17] The flagship-level Europa Jupiter System Mission was in the works in the early 2000s, but funding issues resulted in it evolving into ESA's Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer.[19]

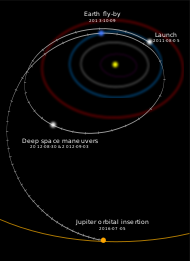

Juno completed a five-year cruise to Jupiter, arriving on 5 July 2016.[7] The spacecraft traveled a total distance of roughly 2.8×109 km (19 AU; 1.7×109 mi) to reach Jupiter.[20] The spacecraft was designed to orbit Jupiter 37 times over the course of its mission. This was originally planned to take 20 months.[4][5]

Juno's trajectory used a gravity assist speed boost from Earth, accomplished by an Earth flyby in October 2013, two years after its launch on 5 August 2011.[21] The spacecraft performed an orbit insertion burn to slow it enough to allow capture. It was expected to make three 53-day orbits before performing another burn on 11 December 2016, that would bring it into a 14-day polar orbit called the Science Orbit. Because of a suspected problem in Juno's main engine, the burn scheduled on 11 December 2016 was cancelled, and Juno will remain in its 53-day orbit until the first Ganymede encounter of its Extended Mission.[22] This extended mission began with a flyby of Ganymede on 7 June 2021.[23]

During the science mission, infrared and microwave instruments will measure the thermal radiation emanating from deep within Jupiter's atmosphere. These observations will complement previous studies of its composition by assessing the abundance and distribution of water, and therefore oxygen. This data will provide insight into Jupiter's origins. Juno will also investigate the convection that drives natural circulation patterns in Jupiter's atmosphere. Other instruments aboard Juno will gather data about its gravitational field and polar magnetosphere. The Juno mission was planned to conclude in February 2018, after completing 37 orbits of Jupiter. The probe was then intended to be deorbited and burn up in Jupiter's outer atmosphere,[4][5] to avoid any possibility of impact and biological contamination of one of its moons.[26]

Flight trajectory[]

Launch[]

Juno was launched atop the Atlas V at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station (CCAFS), Florida. The Atlas V (AV-029) used a Russian-built RD-180 main engine, powered by kerosene and liquid oxygen. At ignition it underwent checkout 3.8 seconds prior to the ignition of five strap-on solid rocket boosters (SRBs). Following the SRB burnout, about 93 seconds into the flight, two of the spent boosters fell away from the vehicle, followed 1.5 seconds later by the remaining three. When heating levels had dropped below predetermined limits, the payload fairing that protected Juno during launch and transit through the thickest part of the atmosphere separated, about 3 minutes 24 seconds into the flight. The Atlas V main engine cut off 4 minutes 26 seconds after liftoff. Sixteen seconds later, the Centaur second stage ignited, and it burned for about 6 minutes, putting the satellite into an initial parking orbit.[27] The vehicle coasted for about 30 minutes, and then the Centaur was reignited for a second firing of 9 minutes, placing the spacecraft on an Earth escape trajectory in a heliocentric orbit.[27]

Prior to separation, the Centaur stage used onboard reaction engines to spin Juno up to 1.4 r.p.m.. About 54 minutes after launch, the spacecraft separated from the Centaur and began to extend its solar panels.[27] Following the full deployment and locking of the solar panels, Juno's batteries began to recharge. Deployment of the solar panels reduced Juno's spin rate by two-thirds. The probe is spun to ensure stability during the voyage and so that all instruments on the probe are able to observe Jupiter.[26][28]

The voyage to Jupiter took five years, and included two orbital maneuvers in August and September 2012 and a flyby of the Earth on 9 October 2013.[29][30] When it reached the Jovian system, Juno had traveled approximately 19 astronomical units (2.8 billion kilometres).[31]

Atlas V on launch pad

Lift-off

Launch video

Flyby of the Earth[]

After traveling for about a year in an elliptical heliocentric orbit, Juno fired its engine twice in 2012 near aphelion (beyond the orbit of Mars) to change its orbit and return to pass by the Earth in October 2013.[29] It used Earth's gravity to help slingshot itself toward the Jovian system in a maneuver called a gravity assist.[33] The spacecraft received a boost in speed of more than 3.9 km/s (8,700 mph), and it was set on a course to Jupiter.[33][34][35] The flyby was also used as a rehearsal for the Juno science team to test some instruments and practice certain procedures before the arrival at Jupiter.[33][36]

Insertion into Jovian orbit[]

Jupiter's gravity accelerated the approaching spacecraft to around 210,000 km/h (130,000 mph).[37] On 5 July 2016, between 03:18 and 03:53 UTC Earth-received time, an insertion burn lasting 2,102 seconds decelerated Juno by 542 m/s (1,780 ft/s)[38] and changed its trajectory from a hyperbolic flyby to an elliptical, polar orbit with a period of about 53.5 days.[39] The spacecraft successfully entered Jovian orbit on 5 July 2016 at 03:53 UTC.[3]

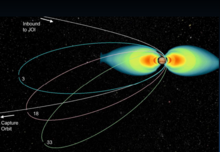

Orbit and environment[]

Juno's highly elliptical initial polar orbit takes it within 4,200 km (2,600 mi) of the planet and out to 8.1×106 km (5.0×106 mi), far beyond Callisto's orbit. An eccentricity-reducing burn, called the Period Reduction Maneuver, was planned that would drop the probe into a much shorter 14 day science orbit.[40] Originally, Juno was expected to complete 37 orbits over 20 months before the end of its mission. Due to problems with helium valves that are important during main engine burns, mission managers announced on 17 February 2017, that Juno would remain in its original 53-day orbit, since the chance of an engine misfire putting the spacecraft into a bad orbit was too high.[22] Juno completed only 12 science orbits before the end of its budgeted mission plan, ending July 2018.[41] In June 2018, NASA extended the mission through July 2021, as described below.

The orbits were carefully planned in order to minimize contact with Jupiter's dense radiation belts, which can damage spacecraft electronics and solar panels, by exploiting a gap in the radiation envelope near the planet, passing through a region of minimal radiation.[8][42] The "Juno Radiation Vault", with 1-centimeter-thick titanium walls, also aids in protecting Juno's electronics.[43] Despite the intense radiation, JunoCam and the Jovian Infrared Auroral Mapper (JIRAM) are expected to endure at least eight orbits, while the Microwave Radiometer (MWR) should endure at least eleven orbits.[44] Juno will receive much lower levels of radiation in its polar orbit than the Galileo orbiter received in its equatorial orbit. Galileo's subsystems were damaged by radiation during its mission, including an LED in its data recording system.[45]

Orbital operations[]

Juno · Jupiter

The spacecraft completed its first flyby of Jupiter (perijove 1) on 26 August 2016, and captured the first images of the planet's north pole.[46]

On 14 October 2016, days prior to perijove 2 and the planned Period Reduction Maneuver, telemetry showed that some of Juno's helium valves were not opening properly.[47] On 18 October 2016, some 13 hours before its second close approach to Jupiter, Juno entered into safe mode, an operational mode engaged when its onboard computer encounters unexpected conditions. The spacecraft powered down all non-critical systems and reoriented itself to face the Sun to gather the most power. Due to this, no science operations were conducted during perijove 2.[48]

On 11 December 2016, the spacecraft completed perijove 3, with all but one instrument operating and returning data. One instrument, JIRAM, was off pending a flight software update.[49] Perijove 4 occurred on 2 February 2017, with all instruments operating.[22] Perijove 5 occurred on 27 March 2017.[50] Perijove 6 took place on 19 May 2017.[50][51]

Although the mission's lifetime is inherently limited by radiation exposure, almost all of this dose was planned to be acquired during the perijoves. As of 2017, the 53.4 day orbit was planned to be maintained through July 2018 for a total of twelve science-gathering perijoves. At the end of this prime mission, the project was planned to go through a science review process by NASA's Planetary Science Division to determine if it will receive funding for an extended mission.[22]

In June 2018, NASA extended the mission operations plan to July 2021.[52] During the mission, the spacecraft will be exposed to high levels of radiation from Jupiter's magnetosphere, which may cause future failure of certain instruments and risk collision with Jupiter's moons.[53][54]

In January 2021, NASA extended the mission operations to September of 2025.[55] In this phase Juno began to examine Jupiter's inner moons, Ganymede, Europa and Io. A flyby of Ganymede occurred on 7 June 2021, 17:35 UTC, coming within 1,038 km (645 mi), the closest any spacecraft has come to the moon since Galileo in 2000.[23][24][56] Then, a flyby of Europa is expected to occur at the end of 2022 at a distance of 320 kilometres (200 miles). Finally, the spacecraft is scheduled to perform two flybys of Io in 2024 at a distance of 1,500 km (930 mi). These flybys will further help with upcoming missions including NASA's Europa Clipper Mission and the European Space Agency's JUICE (JUpiter ICy moons Explorer), as well as the proposed Io Volcano Observer.[57]

Planned deorbit and disintegration[]

NASA originally planned to deorbit the spacecraft into the atmosphere of Jupiter after completing 32 orbits of Jupiter, but has since extended the mission to September 2025.[58][55] The controlled deorbit is intended to eliminate space debris and risks of contamination in accordance with NASA's Planetary Protection Guidelines.[54][53][59]

Team[]

Scott Bolton of the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio, Texas is the principal investigator and is responsible for all aspects of the mission. The Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California manages the mission and the Lockheed Martin Corporation was responsible for the spacecraft development and construction. The mission is being carried out with the participation of several institutional partners. Coinvestigators include of the University of Hawaii, Andrew Ingersoll of California Institute of Technology, Frances Bagenal of the University of Colorado at Boulder, and of the Planetary Science Institute. of the Goddard Space Flight Center served as instrument lead.[60][61]

Cost[]

Juno was originally proposed at a cost of approximately US$700 million (fiscal year 2003) for a launch in June 2009 (equivalent to US$985 million in 2020). NASA budgetary restrictions resulted in postponement until August 2011, and a launch on board an Atlas V rocket in the 551 configuration. As of 2019 the mission was projected to cost US$1.46 billion for operations and data analysis through 2022.[62]

Scientific objectives[]

The Juno spacecraft's suite of science instruments will:[64]

- Determine the ratio of oxygen to hydrogen, effectively measuring the abundance of water in Jupiter, which will help distinguish among prevailing theories linking Jupiter's formation to the Solar System.

- Obtain a better estimate of Jupiter's core mass, which will also help distinguish among prevailing theories linking Jupiter's formation to the Solar System.

- Precisely map Jupiter's gravitational field to assess the distribution of mass in Jupiter's interior, including properties of its structure and dynamics.

- Precisely map Jupiter's magnetic field to assess the origin and structure of the field and how deep in Jupiter the magnetic field is created. This experiment will also help scientists understand the fundamental physics of dynamo theory.

- Map the variation in atmospheric composition, temperature, structure, cloud opacity and dynamics to pressures far greater than 100 bar (10 MPa; 1,500 psi) at all latitudes.

- Characterize and explore the three-dimensional structure of Jupiter's polar magnetosphere and auroras.[64]

- Measure the orbital frame-dragging, known also as Lense–Thirring precession caused by the angular momentum of Jupiter,[65][66] and possibly a new test of general relativity effects connected with the Jovian rotation.[67]

Scientific instruments[]

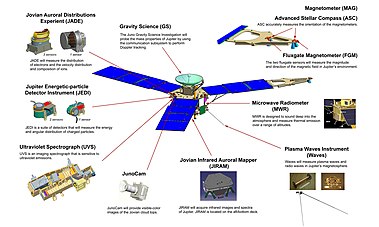

The Juno mission's scientific objectives will be achieved with a payload of nine instruments on board the spacecraft:[68][69][70][71][72]

Microwave radiometer (MWR)[]

The microwave radiometer comprises six antennas mounted on two of the sides of the body of the probe. They will perform measurements of electromagnetic waves on frequencies in the microwave range: 600 MHz, 1.2, 2.4, 4.8, 9.6 and 22 GHz, the only microwave frequencies which are able to pass through the thick Jovian atmosphere. The radiometer will measure the abundance of water and ammonia in the deep layers of the atmosphere up to 200 bar (20 MPa; 2,900 psi) pressure or 500–600 km (310–370 mi) deep. The combination of different wavelengths and the emission angle should make it possible to obtain a temperature profile at various levels of the atmosphere. The data collected will determine how deep the atmospheric circulation is.[73][74] The MWR is designed to function through orbit 11 of Jupiter.[75]

(Principal investigator: Mike Janssen, Jet Propulsion Laboratory)

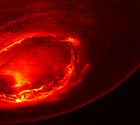

Jovian Infrared Auroral Mapper (JIRAM)[]

The spectrometer mapper JIRAM, operating in the near infrared (between 2 and 5 μm), conducts surveys in the upper layers of the atmosphere to a depth of between 50 and 70 km (31 and 43 mi) where the pressure reaches 5 to 7 bar (500 to 700 kPa). JIRAM will provide images of the aurora in the wavelength of 3.4 μm in regions with abundant H3+ ions. By measuring the heat radiated by the atmosphere of Jupiter, JIRAM can determine how clouds with water are flowing beneath the surface. It can also detect methane, water vapor, ammonia and phosphine. It was not required that this device meets the radiation resistance requirements.[76][77][78] The JIRAM instrument is expected to operate through the eighth orbit of Jupiter.[75]

(Principal investigator: Alberto Adriani, Italian National Institute for Astrophysics)

Magnetometer (MAG)[]

The magnetic field investigation has three goals: mapping of the magnetic field, determining the dynamics of Jupiter's interior, and determination of the three-dimensional structure of the polar magnetosphere. The magnetometer experiment consists of the Flux Gate Magnetometer (FGM), which will observe the strength and direction of the magnetic field lines, and the Advanced Stellar Compass (ASC), which will monitor the orientation of the magnetometer sensors.[70]

(Principal investigator: Jack Connerney, NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center)

Gravity Science (GS)[]

The purpose of measuring gravity by radio waves is to establish a map of the distribution of mass inside Jupiter. The uneven distribution of mass in Jupiter induces small variations in gravity all along the orbit followed by the probe when it runs closer to the surface of the planet. These gravity variations drive small probe velocity changes. The purpose of radio science is to detect the Doppler effect on radio broadcasts issued by Juno toward Earth in Ka-band and X-band, which are frequency ranges that can conduct the study with fewer disruptions related to the solar wind or Jupiter's ionosphere.[79][80][69]

(Principal investigator: John Anderson, Jet Propulsion Laboratory; Principal investigator (Juno's Ka-band Translator): Luciano Iess, Sapienza University of Rome)

Jovian Auroral Distributions Experiment (JADE)[]

The energetic particle detector JADE will measure the angular distribution, energy, and the velocity vector of ions and electrons at low energy (ions between 13 eV and 20 KeV, electrons of 200 eV to 40 KeV) present in the aurora of Jupiter. On JADE, like JEDI, the electron analyzers are installed on three sides of the upper plate which allows a measure of frequency three times higher.[69][81]

(Principal investigator: David McComas, Southwest Research Institute)

Jovian Energetic Particle Detector Instrument (JEDI)[]

The energetic particle detector JEDI will measure the angular distribution and the velocity vector of ions and electrons at high energy (ions between 20 keV and 1 MeV, electrons from 40 to 500 keV) present in the polar magnetosphere of Jupiter. JEDI has three identical sensors dedicated to the study of particular ions of hydrogen, helium, oxygen and sulfur.[69][82]

(Principal investigator: Barry Mauk, Applied Physics Laboratory)

Radio and Plasma Wave Sensor (Waves)[]

This instrument will identify the regions of auroral currents that define Jovian radio emissions and acceleration of the auroral particles by measuring the radio and plasma spectra in the auroral region. It will also observe the interactions between Jupiter's atmosphere and magnetosphere. The instrument consists of two antennae that detect radio and plasma waves.[70]

(Principal investigator: William Kurth, University of Iowa)

Ultraviolet Spectrograph (UVS)[]

UVS will record the wavelength, position and arrival time of detected ultraviolet photons during the time when the spectrograph slit views Jupiter during each turn of the spacecraft. The instrument will provide spectral images of the UV auroral emissions in the polar magnetosphere.[70]

(Principal investigator: G. Randall Gladstone, Southwest Research Institute)

JunoCam (JCM)[]

A visible light camera/telescope, included in the payload to facilitate education and public outreach; later re-purposed to study the dynamics of Jupiter's clouds, particularly those at the poles.[83] It was anticipated that it would operate through only eight orbits of Jupiter ending in September 2017 [84] due to the planet's damaging radiation and magnetic field,[75] but as of June 2021 (34 orbits), JunoCam remains operational.[85]

(Principal investigator: Michael C. Malin, Malin Space Science Systems)

Operational components[]

Solar panels[]

Juno is the first mission to Jupiter to use solar panels instead of the radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTG) used by Pioneer 10, Pioneer 11, the Voyager program, Ulysses, Cassini–Huygens, New Horizons, and the Galileo orbiter.[86] It is also the farthest solar-powered trip in the history of space exploration.[87] Once in orbit around Jupiter, Juno receives only 4% as much sunlight as it would on Earth, but the global shortage of plutonium-238,[88][89][90][91] as well as advances made in solar cell technology over the past several decades, makes it economically preferable to use solar panels of practical size to provide power at a distance of 5 a.u. from the Sun.[citation needed]

The Juno spacecraft uses three solar panels symmetrically arranged around the spacecraft. Shortly after it cleared Earth's atmosphere, the panels were deployed. Two of the panels have four hinged segments each, and the third panel has three segments and a magnetometer. Each panel is 2.7 by 8.9 m (8 ft 10 in by 29 ft 2 in) long,[92] the biggest on any NASA deep-space probe.[93]

The combined mass of the three panels is nearly 340 kg (750 lb).[94] If the panels were optimized to operate at Earth, they would produce 12 to 14 kilowatts of power. Only about 486 watts were generated when Juno arrived at Jupiter, projected to decline to near 420 watts as radiation degrades the cells.[95] The solar panels will remain in sunlight continuously from launch through the end of the mission, except for short periods during the operation of the main engine and eclipses by Jupiter. A central power distribution and drive unit monitors the power that is generated by the solar panels and distributes it to instruments, heaters, and experiment sensors, as well as to batteries that are charged when excess power is available. Two 55 Ah lithium-ion batteries that are able to withstand the radiation environment of Jupiter provide power when Juno passes through eclipse.[96]

Telecommunications[]

Juno uses in-band signaling ("tones") for several critical operations as well as status reporting during cruise mode,[97] but it is expected to be used infrequently. Communications are via the 34 m (112 ft) and 70 m (230 ft) antennas of the NASA Deep Space Network (DSN) utilizing an X-band direct link.[96] The command and data processing of the Juno spacecraft includes a flight computer capable of providing about 50 Mbit/s of instrument throughput. Gravity science subsystems use the X-band and Ka-band Doppler tracking and autoranging.[citation needed]

Due to telecommunications constraints, Juno will only be able to return about 40 megabytes of JunoCam data during each 11-day orbital period, limiting the number of images that are captured and transmitted during each orbit to somewhere between 10 and 100 depending on the compression level used.[98][needs update] The overall amount of data downlinked on each orbit is significantly higher and used for the mission's scientific instruments; JunoCam is intended for public outreach and is thus secondary to the science data. This is comparable to the previous Galileo mission that orbited Jupiter, which captured thousands of images[99] despite its slow data rate of 1000 bit/s (at maximum compression level) due to the failure of its high gain antenna.

The communication system is also used as part of the Gravity Science experiment.[citation needed]

Propulsion[]

Juno uses a LEROS 1b main engine with hypergolic propellant, manufactured by Moog Inc in Westcott, Buckinghamshire, England.[100] It uses hydrazine and nitrogen tetroxide for propulsion and provides a thrust of 645 newtons. The engine bell is enclosed in a debris shield fixed to the spacecraft body, and is used for major burns. For control of the vehicle's orientation (attitude control) and to perform trajectory correction maneuvers, Juno utilizes a monopropellant reaction control system (RCS) consisting of twelve small thrusters that are mounted on four engine modules.[96]

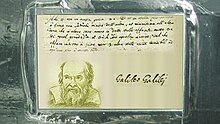

Galileo plaque and minifigures[]

Juno carries a plaque to Jupiter, dedicated to Galileo Galilei. The plaque was provided by the Italian Space Agency (ASI) and measures 7.1 by 5.1 cm (2.8 by 2.0 in). It is made of flight-grade aluminum and weighs 6 g (0.21 oz).[101] The plaque depicts a portrait of Galileo and a text in Galileo's own handwriting, penned in January 1610, while observing what would later be known to be the Galilean moons.[101] The text translates as:

On the 11th it was in this formation – and the star closest to Jupiter was half the size than the other and very close to the other so that during the previous nights all of the three observed stars looked of the same dimension and among them equally afar; so that it is evident that around Jupiter there are three moving stars invisible till this time to everyone.

The spacecraft also carries three Lego minifigures representing Galileo Galilei, the Roman god Jupiter, and his sister and wife, the goddess Juno. In Roman mythology, Jupiter drew a veil of clouds around himself to hide his mischief. Juno was able to peer through the clouds and reveal Jupiter's true nature. The Juno minifigure holds a magnifying glass as a sign of searching for the truth, and Jupiter holds a lightning bolt. The third Lego crew member, Galileo Galilei, has his telescope with him on the journey.[102] The figurines were produced in partnership between NASA and Lego as part of an outreach program to inspire children's interest in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM).[103] Although most Lego toys are made of plastic, Lego specially made these minifigures of aluminum to endure the extreme conditions of space flight.[104]

Scientific results[]

Among early results, Juno gathered information about Jovian lightning that revised earlier theories.[105] Juno provided the first views of Jupiter's north pole, as well as providing insight about Jupiter's aurorae, magnetic field, and atmosphere.[106] In 2021, analysis of the spacecraft's dust as it passed through the asteroid belt suggested that Zodiacal light is caused by dust coming from Mars, rather than asteroids or comets as was previously thought.[107]

Timeline[]

| Date (UTC) | Event |

|---|---|

| 5 August 2011, 16:25:00 | Launched [108] |

| 5 August 2012, 06:57:00 | Trajectory corrections [109] |

| 3 September 2012, 06:30:00 | |

| 9 October 2013, 19:21:00 | Earth gravity assist (from 126,000 to 150,000 km/h (78,000 to 93,000 mph))[110] — Gallery |

| 5 July 2016, 03:53:00 | Arrival at Jupiter and polar orbit insertion (1st orbit).[4][5] |

| 27 August 2016, 12:50:44 | Perijove 1 [111] — Gallery |

| 19 October 2016, 18:10:53 | Perijove 2: Planned Period Reduction Maneuver, but the main engine's fuel pressurisation system did not operate as expected.[112] |

| 11 December 2016, 17:03:40 | Perijove 3 [113][114] |

| 2 February 2017, 12:57:09 | Perijove 4 [114][115] |

| 27 March 2017, 08:51:51 | Perijove 5 [50] |

| 19 May 2017, 06:00:47 | Perijove 6 [51] |

| 11 July 2017, 01:54:42 | Perijove 7: Flyover of the Great Red Spot [116][117] |

| 1 September 2017, 21:48:50 | Perijove 8 [118] |

| 24 October 2017, 17:42:31 | Perijove 9 [119] |

| 16 December 2017, 17:56:59 | Perijove 10 [120][121] |

| 7 February 2018, 13:51:49 | Perijove 11 [108] |

| 1 April 2018, 09:45:57 | Perijove 12 [108] |

| 24 May 2018, 05:40:07 | Perijove 13 [108] |

| 16 July 2018, 05:17:38 | Perijove 14 [108] |

| 7 September 2018, 01:11:55 | Perijove 15 [108] |

| 29 October 2018, 21:06:15 | Perijove 16 [108] |

| 21 December 2018, 17:00:25 | Perijove 17 [122][108] |

| 12 February 2019, 16:19:48 | Perijove 18 [108] |

| 6 April 2019, 12:13:58 | Perijove 19 [108] |

| 29 May 2019, 08:08:13 | Perijove 20 [108] |

| 21 July 2019, 04:02:44 | Perijove 21 [123][108] |

| 12 September 2019, 03:40:47 | Perijove 22 [123][108] |

| 3 November 2019, 23:32:56 | Perijove 23 [108] |

| 26 December 2019, 16:58:59 | Perijove 24 [108] |

| 17 February 2020, 17:51:36 | Perijove 25 [108] |

| 10 April 2020, 14:24:34 | Perijove 26 [108] |

| 2 June 2020, 10:19:55 | Perijove 27 [108] |

| 25 July 2020, 06:15:21 | Perijove 28 [108] |

| 16 September 2020, 02:10:49 | Perijove 29 [108] |

| 8 November 2020, 01:49:39 | Perijove 30 [108] |

| 30 December 2020, 21:45:12 | Perijove 31 [108] |

| 21 February 2021, 17:40:31 | Perijove 32 [108] |

| 15 April 2021, 13:36:26 | Perijove 33 [108][124] |

| 7 June 2021, 09:32:03 | Perijove 34: Ganymede flyby, coming within 1,038 km (645 mi) of the moon's surface.[23] Orbital period reduced from 53 days to 43 days.[125][108] |

| 20 July 2021 | Perijove 35: End of first mission extension.[125] Originally scheduled for 30 July 2021 prior to approval of second mission extension.[126] |

| 29 September 2022 | Perijove 45: Europa flyby. Orbital period reduced from 43 days to 38 days.[125] |

| 30 December 2023 | Perijove 57: Io flyby.[125] |

| 3 February 2024 | Perijove 58: Io flyby. Orbital period reduced to 33 days.[125] |

| September 2025 | Perijove 76: End of second mission extension.[125] |

Gallery[]

Jupiter[]

Perijove 26 image

Image from about 94,500 km (58,700 mi) of Jupiter's southern polar region (27 August 2016)

Jupiter growing and shrinking in apparent size before and after the spacecraft made its closest approach (27 August 2016)

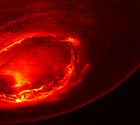

Infrared view of the southern aurora of Jupiter (27 August 2016)

Southern storms of Jupiter

Area of Jupiter where multiple atmospheric conditions appear to collide (27 March 2017)

Retreating from Jupiter, about 46,900 km (29,100 mi) above the cloud tops (19 May 2017)

Image taken from 16,535 km (10,274 mi) above the atmosphere at a latitude of -36.9° (10 July 2017)

Closeup of the Great Red Spot taken from about 8,000 km (5,000 mi) above it (11 July 2017)

Jupiter viewed by Juno

Jupiter viewed by Juno

(12 February 2019)- Jupiter flyover

(Juno; 05:07; 2 June 2020)

Moons[]

Low resolution view of Io captured by JunoCam (September 2017)

Plume near Io's terminator (21 December 2018)[127]

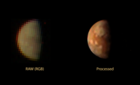

Ganymede, taken by the JunoCam instrument during Juno's flyby on 8 June 2021

Infrared view of Ganymede during the anniversary flyby by Juno

See also[]

- Atmosphere of Jupiter

- Comet Shoemaker–Levy 9

- Europa Clipper

- Exploration of Jupiter

- Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer

- List of missions to the outer planets

- Moons of Jupiter

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Juno Mission to Jupiter" (PDF). NASA FACTS. NASA. April 2009. p. 1. Archived from the original on 25 December 2018. Retrieved 5 April 2011.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Jupiter Orbit Insertion Press Kit" (PDF). NASA. 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 August 2016. Retrieved 7 July 2016.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Foust, Jeff (5 July 2016). "Juno enters orbit around Jupiter". SpaceNews. Archived from the original on 31 December 2016. Retrieved 25 August 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Chang, Kenneth (5 July 2016). "NASA's Juno Spacecraft Enters Jupiter's Orbit". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2 May 2019. Retrieved 5 July 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Greicius, Tony (21 September 2015). "Juno – Mission Overview". NASA. Archived from the original on 25 December 2018. Retrieved 2 October 2015.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Dunn, Marcia (5 August 2011). "NASA probe blasts off for Jupiter after launch-pad snags". NBC News. Archived from the original on 14 September 2019. Retrieved 31 August 2011.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Chang, Kenneth (28 June 2016). "NASA's Juno Spacecraft Will Soon Be in Jupiter's Grip". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 14 August 2018. Retrieved 30 June 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Riskin, Dan (4 July 2016). Mission Jupiter (Television documentary). Science Channel.

- ^ Cheng, Andrew; Buckley, Mike; Steigerwald, Bill (21 May 2008). "Winds in Jupiter's Little Red Spot Almost Twice as Fast as Strongest Hurricane". NASA. Archived from the original on 13 May 2017. Retrieved 9 August 2017.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Juno's Solar Cells Ready to Light Up Jupiter Mission". NASA. 15 July 2011. Archived from the original on 16 February 2017. Retrieved 4 October 2015.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "NASA's Juno Spacecraft Launches to Jupiter". NASA. 5 August 2011. Archived from the original on 26 April 2020. Retrieved 5 August 2011.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Mission Acronyms & Definitions" (PDF). NASA. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 September 2020. Retrieved 30 April 2016.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Juno Launch Press Kit, Quick Facts" (PDF). jpl.nasa.gov. Jet Propulsion Lab. August 2011. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 June 2019. Retrieved 23 May 2019.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Leone, Dan (23 February 2015). "NASA Sets Next US$1 Billion New Frontiers Competition for 2016". SpaceNews. Retrieved 2 January 2017.

- ^ Hillger, Don; Toth, Garry (20 September 2016). "New Frontiers-series satellites". Colorado State University. Archived from the original on 30 November 2016. Retrieved 2 January 2017.

- ^ "Juno Mission to Jupiter". Astrobiology Magazine. 9 June 2005. Archived from the original on 20 June 2018. Retrieved 7 December 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ludwinski, Jan M.; Guman, Mark D.; Johannesen, Jennie R.; Mitchell, Robert T.; Staehle, Robert L. (1998). The Europa Orbiter Mission Design. 49th International Astronautical Congress, September 28 – October 2, 1998, Melbourne, Australia. hdl:2014/20516.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Zeller, Martin (January 2001). "NASA Announces New Discovery Program Awards". NASA and University of Southern California. Archived from the original on 5 March 2017. Retrieved 25 December 2016.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Dougherty, M. K.; Grasset, O.; Bunce, E.; Coustenis, A.; Titov, D. V.; et al. (2011). JUICE (JUpiter ICy moon Explorer): a European-led mission to the Jupiter system (PDF). EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2011, October 2–7, 2011, Nantes, France. Bibcode:2011epsc.conf.1343D. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 November 2011. Retrieved 25 December 2016.

- ^ Dunn, Marcia (1 August 2011). "NASA going green with solar-powered Jupiter probe". USA Today. Archived from the original on 26 April 2020. Retrieved 24 October 2015.

- ^ "NASA's Shuttle and Rocket Launch Schedule". NASA. Archived from the original on 13 September 2008. Retrieved 17 February 2011.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Brown, Dwayne; Cantillo, Laurie; Agle, D. C. (17 February 2017). "NASA's Juno Mission to Remain in Current Orbit at Jupiter" (Press release). NASA. Archived from the original on 20 February 2017. Retrieved 13 March 2017.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Greicius, Tony (3 June 2021). "NASA's Juno to Get a Close Look at Jupiter's Moon Ganymede". NASA. Archived from the original on 3 June 2021. Retrieved 4 June 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "See the First Images NASA's Juno Took as It Sailed by Ganymede | NASA".

- ^ "NASA's Juno Mission Expands Into the Future" (Press release). NASA. 13 January 2021. Archived from the original on 23 January 2021. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Juno Mission Profile & Timeline Archived November 25, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Atlas/Juno launch timeline". Spaceflight Now. 28 July 2011. Archived from the original on 17 March 2021. Retrieved 29 July 2011.

- ^ "Juno's Solar Cells Ready to Light Up Jupiter Mission". NASA. 27 June 2016. Archived from the original on 26 April 2020. Retrieved 5 July 2016.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Whigham, Nick (7 July 2016). "The success of Juno's Jupiter mission has its origins in a famous idea from more than 50 years ago". news.com.au. Archived from the original on 6 January 2019. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- ^ Wall, Mike (9 October 2013). "NASA Spacecraft Slingshots By Earth On Way to Jupiter, Snaps Photos". Space.com. Archived from the original on 6 January 2019. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- ^ Agle, D. C. (12 August 2013). "NASA's Juno is Halfway to Jupiter". NASA/JPL. Archived from the original on 2 August 2020. Retrieved 12 August 2013.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Greicius, Tony, ed. (25 March 2014). "Earth Triptych from NASA's Juno Spacecraft". NASA. Archived from the original on 13 November 2016. Retrieved 26 November 2017.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Earth Flyby – Mission Juno". missionjuno.swri.edu. Archived from the original on 3 October 2015. Retrieved 2 October 2015.

- ^ "NASA's Juno Gives Starship-Like View of Earth Flyby". 13 February 2015. Archived from the original on 3 March 2020. Retrieved 2 October 2015.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Greicius, Tony (26 August 2013). "Juno Earth Flyby". NASA. Archived from the original on 26 April 2020. Retrieved 8 October 2015.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Greicius, Tony (13 February 2015). "NASA's Juno Gives Starship-Like View of Earth Flyby". Archived from the original on 3 March 2020. Retrieved 5 July 2016.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Chang, Kenneth (5 July 2016). "NASA's Juno Spacecraft Enters Jupiter's Orbit". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2 May 2019. Retrieved 5 July 2016.

- ^ "NASA's Juno Spacecraft in Orbit Around Mighty Jupiter". NASA. 4 July 2016. Archived from the original on 6 July 2016. Retrieved 5 July 2016.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Clark, Stephen (4 July 2016). "Live coverage: NASA's Juno spacecraft arrives at Jupiter". Spaceflight Now. Archived from the original on 5 July 2016. Retrieved 5 July 2016.

- ^ Gebhardt, Chris (3 September 2016). "Juno provides new data on Jupiter; readies for primary science mission". NASASpaceflight.com. Archived from the original on 20 October 2016. Retrieved 23 October 2016.

- ^ Clark, Stephen (21 February 2017). "NASA's Juno spacecraft to remain in current orbit around Jupiter". Spaceflight Now. Archived from the original on 26 February 2017. Retrieved 26 April 2017.

- ^ Moomaw, Bruce (11 March 2007). "Juno Gets A Little Bigger With One More Payload For Jovian Delivery". Space Daily. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 31 August 2011.

- ^ "Juno Armored Up to Go to Jupiter". NASA. 12 July 2010. Archived from the original on 13 August 2016. Retrieved 11 July 2016.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Understanding Juno's Orbit: An Interview with NASA's Scott Bolton". universetoday.com. 8 January 2016. Archived from the original on 7 February 2016. Retrieved 6 February 2016.

- ^ Webster, Guy (17 December 2002). "Galileo Millennium Mission Status". NASA – Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Archived from the original on 24 November 2020. Retrieved 22 February 2017.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Firth, Niall (5 September 2016). "NASA's Juno probe snaps first images of Jupiter's north pole". New Scientist. Archived from the original on 6 September 2016. Retrieved 5 September 2016.

- ^ Agle, D. C.; Brown, Dwayne; Cantillo, Laurie (15 October 2016). "Mission Prepares for Next Jupiter Pass". NASA. Archived from the original on 17 June 2019. Retrieved 19 October 2016.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Grush, Loren (19 October 2016). "NASA's Juno spacecraft went into safe mode last night". The Verge. Archived from the original on 5 March 2017. Retrieved 23 October 2016.

- ^ "NASA Juno Mission Completes Latest Jupiter Flyby". NASA / Jet Propulsion Laboratory. 9 December 2016. Archived from the original on 17 May 2017. Retrieved 4 February 2017.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Agle, D. C.; Brown, Dwayne; Cantillo, Laurie (27 March 2017). "NASA's Juno Spacecraft Completes Fifth Jupiter Flyby". NASA. Archived from the original on 29 March 2017. Retrieved 31 March 2017.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Anderson, Natali (20 May 2017). "NASA's Juno Spacecraft Completes Sixth Jupiter Flyby". Sci-News. Archived from the original on 25 May 2017. Retrieved 4 June 2017.

- ^ Agle, D. C.; Wendel, JoAnna; Schmid, Deb (6 June 2018). "NASA Re-plans Juno's Jupiter Mission". NASA/JPL. Archived from the original on 24 July 2020. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Dickinson, David (21 February 2017). "Juno Will Stay in Current Orbit Around Jupiter". Sky and Telescope. Archived from the original on 8 January 2018. Retrieved 7 January 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bartels, Meghan (5 July 2016). "To protect potential alien life, NASA will destroy its US$1 billion Jupiter spacecraft on purpose". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 8 January 2018. Retrieved 7 January 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Talbert, Tricia (8 January 2021). "NASA Extends Exploration for Two Planetary Science Missions". NASA. Archived from the original on 11 January 2021. Retrieved 11 January 2021.

- ^ https://archive.today/20210609043534/https://www.theguardian.com/science/2021/jun/08/juno-nasa-jupiter-moon-ganymede

- ^ "Io Volcano Observer proposal selected for further study by NASA's Discovery Program: More Love for Outer Space". www.usgs.gov. Archived from the original on 12 January 2021. Retrieved 11 January 2021.

- ^ "Mission Name: Juno". NASA's Planetary Data System. July 2020. Archived from the original on 11 January 2021. Retrieved 9 January 2021.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "NASA Juno Spacecraft to remain in Elongated Capture Orbit around Jupiter". Spaceflight101.com. 18 February 2017. Archived from the original on 31 October 2017. Retrieved 7 January 2018.

- ^ "Juno Institutional Partners". University of Wisconsin–Madison. 2008. Archived from the original on 15 November 2009. Retrieved 8 August 2009.

- ^ "NASA Sets Launch Coverage Events For Mission To Jupiter". NASA. 27 July 2011. Archived from the original on 17 September 2011. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "The Planetary Exploration Budget Dataset". The Planetary Society. Archived from the original on 12 April 2020. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- ^ "Jupiter Awaits Arrival of Juno". Archived from the original on 28 June 2016. Retrieved 28 June 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Juno Science Objectives". University of Wisconsin–Madison. Archived from the original on 19 September 2015. Retrieved 13 October 2008.

- ^ Iorio, L. (August 2010). "Juno, the angular momentum of Jupiter and the Lense–Thirring effect". New Astronomy. 15 (6): 554–560. arXiv:0812.1485. Bibcode:2010NewA...15..554I. doi:10.1016/j.newast.2010.01.004.

- ^ Helled, R.; Anderson, J.D.; Schubert, G.; Stevenson, D.J. (December 2011). "Jupiter's moment of inertia: A possible determination by Juno". Icarus. 216 (2): 440–448. arXiv:1109.1627. Bibcode:2011Icar..216..440H. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2011.09.016. S2CID 119077359.

- ^ Iorio, L. (2013). "A possible new test of general relativity with Juno". Classical and Quantum Gravity. 30 (18): 195011. arXiv:1302.6920. Bibcode:2013CQGra..30s5011I. doi:10.1088/0264-9381/30/19/195011. S2CID 119301991.

- ^ "Instrument overview". Wisconsin University-Madison. Archived from the original on 16 October 2008. Retrieved 13 October 2008.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Dodge, R.; Boyles, M. A.; Rasbach, C. E. (September 2007). "Key and driving requirements for the Juno payload suite of instruments" (PDF). NASA. GS, p. 8; JADE and JEDI, p. 9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 5 December 2010.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Juno Spacecraft: Instruments". Mission Juno. Southwest Research Institute. Archived from the original on 26 April 2012. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

- ^ "Juno launch: press kit August 2011" (PDF). NASA. pp. 16–20. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 October 2011. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "More and Juno Ka-band transponder design, performance, qualification and in-flight validation" (PDF). Laboratorio di Radio Scienza del Dipartimento di Ingegneria Meccanica e Aerospaziale, università "Sapienza". 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

- ^ Owen, T.; Limaye, S. (23 October 2008). "Instruments : microwave radiometer". University of Wisconsin–Madison. Archived from the original on 28 March 2014.

- ^ "Juno spacecraft MWR". University of Wisconsin–Madison. Archived from the original on 21 August 2015. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "After Five Years in Space, a Moment of Truth". Mission Juno. Southwest Research Institute. Archived from the original on 17 April 2016. Retrieved 18 October 2016.

- ^ "About JIRAM". IAPS (Institute for Space Astrophysics and Planetology of the Italian INAF). Archived from the original on 9 August 2016. Retrieved 27 June 2016.

- ^ Owen, T.; Limaye, S. (23 October 2008). "Instruments : the Jupiter Infrared Aural Mapper". University of Wisconsin–Madison. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016.

- ^ "Juno spacecraft JIRAM". University of Wisconsin–Madison. Archived from the original on 21 August 2015. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- ^ Anderson, John; Mittskus, Anthony (23 October 2008). "Instruments: Gravity Science Experiment". University of Wisconsin–Madison. Archived from the original on 4 February 2016.

- ^ "Juno spacecraft GS". University of Wisconsin–Madison. Archived from the original on 21 August 2015. Retrieved 31 December 2015.

- ^ "Juno spacecraft JADE". University of Wisconsin–Madison. Archived from the original on 21 August 2015. Retrieved 31 December 2015.

- ^ "Juno spacecraft JEDI". University of Wisconsin–Madison. Archived from the original on 21 August 2015. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- ^ Agle, D. C.; Brown, Dwayne; Wendel, JoAnna; Schmid, Deb (12 December 2018). "NASA's Juno Mission Halfway to Jupiter Science". NASA/JPL. Archived from the original on 14 December 2018. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Understanding Juno's Orbit: An Interview with NASA's Scott Bolton". Universe Today. 8 January 2016. Archived from the original on 7 February 2016. Retrieved 6 February 2016.

- ^ "Ganymede in True (RGB) and False (GRB) Colour". JunoCam Image Processing. NASA, SwRI, MSSS. 12 June 2021. Retrieved 13 June 2021.

- ^ "Cruising to Jupiter: A Powerful Math Lesson – Teachable Moments". NASA/JPL Edu. Archived from the original on 20 March 2021. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ^ "NASA's Juno Mission to Jupiter to Be Farthest Solar-Powered Trip". Archived from the original on 3 October 2015. Retrieved 2 October 2015.

- ^ David Dickinson (21 March 2013). "U.S. to restart plutonium production for deep space exploration". Universe Today. Archived from the original on 17 March 2021. Retrieved 15 February 2015.

- ^ Greenfieldboyce, Nell. "Plutonium Shortage Could Stall Space Exploration". NPR. Archived from the original on 3 August 2020. Retrieved 10 December 2013.

- ^ Greenfieldboyce, Nell. "The Plutonium Problem: Who Pays For Space Fuel?". NPR. Archived from the original on 3 May 2018. Retrieved 10 December 2013.

- ^ Wall, Mike. "Plutonium Production May Avert Spacecraft Fuel Shortage". Archived from the original on 2 July 2013. Retrieved 10 December 2013.

- ^ "Juno Solar Panels Complete Testing". NASA. 24 June 2016. Archived from the original on 23 March 2021. Retrieved 5 July 2016.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ NASA's Juno Spacecraft Launches to Jupiter Archived 26 April 2020 at the Wayback Machine "... and that its massive solar arrays, the biggest on any NASA deep-space probe, have deployed and are generating power".

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Juno's Solar Cells Ready to Light Up Jupiter Mission". Archived from the original on 25 December 2014. Retrieved 19 June 2014.

- ^ "Juno prepares for mission to Jupiter". Machine Design. Archived from the original on 31 October 2010. Retrieved 2 November 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Juno Spacecraft Information – Power Distribution". Spaceflight 101.com. 2011. Archived from the original on 25 November 2011. Retrieved 6 August 2011.

- ^ "Key Terms". Mission Juno. Southwest Research Institute. Section TONES. Archived from the original on 5 May 2016.

- ^ "Junocam will get us great global shots down onto Jupiter's poles". Archived from the original on 16 March 2013. Retrieved 6 July 2016.

- ^ "Overview | Galileo". solarsystem.nasa.gov. NASA. Archived from the original on 15 February 2017. Retrieved 14 May 2021.

- ^ Amos, Jonathan (4 September 2012). "Juno Jupiter probe gets British boost". BBC News. Archived from the original on 17 July 2018. Retrieved 4 September 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Juno Jupiter Mission to Carry Plaque Dedicated to Galileo". NASA. 3 August 2011. Archived from the original on 8 May 2020. Retrieved 5 August 2011.

- ^ "Juno Spacecraft to Carry Three Lego minifigures to Jupiter Orbit". NASA. 3 August 2011. Archived from the original on 8 May 2020. Retrieved 5 August 2011.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Juno Spacecraft to Carry Three Figurines to Jupiter Orbit". NASA. 3 August 2011. Archived from the original on 22 December 2016. Retrieved 25 December 2016.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Pachal, Peter (5 August 2011). "Jupiter Probe Successfully Launches With Lego On Board". PC Magazine. Archived from the original on 4 July 2017. Retrieved 2 September 2017.

- ^ Connerney, John; et al. (June 2018). "Prevalent lightning sferics at 600 megahertz near Jupiter's poles". Nature. 558 (7708): 87–90. Bibcode:2018Natur.558...87B. doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0156-5. PMID 29875484. S2CID 46952214.

- ^ "Overview | Juno". NASA. Archived from the original on 19 May 2021. Retrieved 19 May 2021.

- ^ Shekhtman, Lonnie (9 March 2021). "Serendipitous Juno Detections Shatter Ideas About Origin of Zodiacal Light". Jet Propulsion Laboratory. NASA. Archived from the original on 18 March 2021. Retrieved 19 March 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y "PDS: Mission Information". Planetary Data System. NASA. Archived from the original on 1 March 2021. Retrieved 14 May 2021.

- ^ Agle, D. C.; Martinez, Maria (17 September 2012). "Juno's Two Deep Space Maneuvers are 'Back-To-Back Home Runs'". NASA/JPL. Archived from the original on 2 August 2020. Retrieved 12 October 2015.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Juno Earth Flyby – 9 October 2013". NASA. 26 August 2013. Archived from the original on 26 April 2020. Retrieved 4 July 2016.

- ^ Agle, D. C.; Brown, Dwayne; Cantillo, Laurie (27 August 2016). "NASA's Juno Successfully Completes Jupiter Flyby". NASA. Archived from the original on 9 March 2021. Retrieved 1 October 2016.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Mission Prepares for Next Jupiter Pass". Mission Juno. Southwest Research Institute. 14 October 2016. Archived from the original on 17 March 2021. Retrieved 15 October 2016.

- ^ Agle, D. C.; Brown, Dwayne; Cantillo, Laurie (12 December 2016). "NASA Juno Mission Completes Latest Jupiter Flyby". NASA – Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Archived from the original on 17 May 2017. Retrieved 12 December 2016.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Thompson, Amy (10 December 2016). "NASA's Juno Spacecraft Preps for Third Science Orbit". Inverse. Archived from the original on 17 March 2021. Retrieved 12 December 2016.

- ^ "It's Never 'Groundhog Day' at Jupiter". NASA – Jet Propulsion Laboratory. 1 February 2017. Archived from the original on 22 September 2020. Retrieved 4 February 2017.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Witze, Alexandra (25 May 2017). "Jupiter's secrets revealed by NASA probe". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2017.22027. Archived from the original on 4 June 2017. Retrieved 14 June 2017.

- ^ Lakdawalla, Emily (3 November 2016). "Juno update: 53.5-day orbits for the foreseeable future, more Marble Movie". The Planetary Society. Archived from the original on 26 April 2020. Retrieved 14 June 2017.

- ^ "Photos from Juno's Seventh Science Flyby of Jupiter". Spaceflight101.com. 8 September 2017. Archived from the original on 13 February 2018. Retrieved 12 February 2018.

- ^ Mosher, Dave (7 November 2017). "NASA's US$1 billion Jupiter probe just sent back stunning new photos of the gas giant". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 4 March 2018. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- ^ "Juno's Perijove-10 Jupiter Flyby, Reconstructed in 125-Fold Time-Lapse". NASA / JPL / SwRI / MSSS / SPICE / Gerald Eichstädt. 25 December 2017. Archived from the original on 13 February 2018. Retrieved 12 February 2018.

- ^ "Overview of Juno's Perijove 10". The Planetary Society. 16 December 2017. Archived from the original on 13 February 2018. Retrieved 12 February 2018.

- ^ Boyle, Alan (26 December 2018). "Ho, ho, Juno! NASA orbiter delivers lots of holiday goodies from Jupiter's north pole". geekwire.com. Archived from the original on 26 April 2019. Retrieved 7 February 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Lakdawalla, Emily (3 November 2016). "Juno update: 53.5-day orbits for the foreseeable future, more Marble Movie". Planetary Society. Archived from the original on 26 April 2020. Retrieved 25 December 2018.

- ^ Greicius, Tony (18 May 2021). "Juno Returns to "Clyde's Spot" on Jupiter". NASA. Archived from the original on 27 May 2021. Retrieved 4 June 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f "NASA's Juno Mission Expands Into the Future". NASA. 13 January 2021. Archived from the original on 13 January 2021. Retrieved 13 January 2021.

- ^ Wall, Mike (8 June 2018). "NASA Extends Juno Jupiter Mission Until July 2021". Space.com. Archived from the original on 23 June 2018. Retrieved 23 June 2018.

- ^ "Juno mission captures images of volcanic plumes on Jupiter's moon Io". Southwest Research Institute. 31 December 2018. Archived from the original on 3 January 2019. Retrieved 2 January 2019.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Juno. |

| Wikinews has related news: |

- Official website

- Juno mission at Southwest Research Institute

- Juno Mission at NASA's Solar System Exploration

- Why With Nye playlist on YouTube, Bill Nye discussing the science behind NASA's Juno mission to Jupiter

- JunoCam image processing web site

- Animation of perijove 15 flyby by Gerald Eichstädt (see channel for more)

- Animation of perijove 16 flyby by Gerald Eichstädt and Seán Doran (see albums 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 20 21, 23, 24 and 25 for more)

- Juno image album by Kevin M. Gill

- Juno (spacecraft)

- NASA space probes

- New Frontiers program

- Lockheed Martin satellites and probes

- Missions to Jupiter

- Orbiters (space probe)

- Space probes launched in 2011

- 2011 in the United States

- Spacecraft launched by Atlas rockets