Justice and Development Party (Turkey)

Justice and Development Party Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi | |

|---|---|

| |

| Abbreviation | AK PARTİ (official)[1] AKP (unofficial)[2] |

| Leader | Recep Tayyip Erdoğan |

| General Secretary | Fatih Şahin |

| Parliamentary Leader | Naci Bostancı |

| Spokesperson | Ömer Çelik |

| Founder | Recep Tayyip Erdoğan |

| Founded | 14 August 2001 |

| Split from | Virtue Party |

| Headquarters | Söğütözü Caddesi No 6 Çankaya, Ankara |

| Youth wing | AK Youth |

| Membership (2021) | |

| Ideology | Conservative democracy[4][5]

Liberal conservatism[23][24] Conservative liberalism[25][26][27] Economic liberalism[28][29] Pro-Europeanism |

| Political position | Right-wing[30][31] to far-right[32] Historical: Centre-right[33] to right-wing[34] |

| National affiliation | People's Alliance |

| European affiliation | Alliance of European Conservatives and Reformists (2013–2018) |

| Colours | Orange Blue |

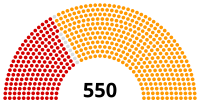

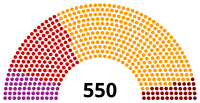

| Grand National Assembly | 288 / 600 |

| Metropolitan municipalities | 15 / 30 |

| District municipalities | 742 / 1,351 |

| Provincial councillors | 757 / 1,251 |

| Municipal Assemblies | 10,173 / 20,498 |

| Party flag | |

| |

| Website | |

| www | |

| |

The Justice and Development Party (Turkish: Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi, AKP), abbreviated officially AK Parti in Turkish, is a conservative and populist political party in Turkey. As of 2021 the party is the largest in Turkey and has been in power almost continuously since 2003, with its leader Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, prime minister or president during most of this time, and still president as of 2021. The party suffered a setback in the 2019 local elections, losing Istanbul and Ankara and other large cities, in addition to losses attributed to the Turkish economic crisis, accusations of authoritarianism, as well as alleged government inaction on the Syrian refugee crisis.[35][36]

Founded in 2001, the party has a strong base of support among orthodox Muslims and arose from the conservative tradition of Turkey's Ottoman past and its Islamic identity,[37] though the party strongly denies it is Islamist.[38] The party originally worked with the Islamic Gülen movement,[39] positioned itself as a pro-Western, pro-American,[40] pro-liberal market economy, supporting Turkish membership in the European Union.[41] (As of 2021, the US is threatening sanctions against the AKP government for its purchase of Russian missiles.[42] AKP broke with the Gülen movement after the 2013 corruption investigations of officials in the AKP,[43][44] and the Gülen movement is now classified as a terrorist organization in Turkey.)[45]

The party has been credited by many with passing a series of reforms from 2002 to 2011 that increased accessibility to healthcare and housing, distributed food subsidies, increased funding for students, improved infrastructure in poorer districts, privatized state-owned businesses, increased civilian oversight of the powerful military, overcame economic crises and oversaw high rates of growth of GDP and per capita income.[46]

The AKP government has also lifted bans on religious and conservative dress (e.g. hijab) in universities and public institutions, helped Islamic schools, brought about tighter regulations on abortion and higher taxes on alcohol consumption. This has brought allegations that it is covertly undermining Turkish constitutional secular principles (the Turkish constitution forbids sharia in the legal code or religious political parties, and courts have banned several parties for violating secular principles) and led to two unsuccessful court cases attempting to close the party in 2002 and 2008.[47]

More recently, in 2013, nationwide protests broke out against the alleged authoritarianism of the AKP government, the party's EU accession negotiations have stalled,[48] the AKP government has been accused of crony capitalism,[49] and criticized its plans to centralized power in the Turkish state,[50] and restrictions on civil liberties such as temporarily blocking access to Twitter and YouTube in March 2014.[51]

As of 2021, the Justice and Development Party is the fifth largest political party in the world by membership and is the largest political party outside of China, India, or the United States.

History[]

Founded in 2001, by members of a number of existing conservative Islamic parties, the original and current party leader is Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, the incumbent President of Turkey.

Formation[]

The AKP was established by a wide range of politicians of various political parties and a number of new politicians in 2001. The core of the party was formed from the reformist faction of the Islamist Virtue Party, including people such as Abdullah Gül and Bülent Arınç, while a second founding group consisted of members of the social conservative Motherland Party who had been close to Turgut Özal, such as Cemil Çiçek and Abdülkadir Aksu. Some members of the True Path Party, such as Hüseyin Çelik and Köksal Toptan, joined the AKP. Some members, such as Kürşad Tüzmen had nationalist or Ertuğrul Günay, had center-left backgrounds while representatives of the nascent 'Muslim left' current were largely excluded.[52] In addition. a large number of people joined a political party for the first time, such as Ali Babacan, Selma Aliye Kavaf, Egemen Bağış and Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu.

Closure cases[]

Controversies over whether the party remains committed to secular principles enshrined in the Turkish constitution have dominated Turkish politics since 2002. Turkey's constitution established the country as a secular state and prohibits any political parties that promote Islamism or shariah law.

Since coming to power, the party has brought about tighter regulations on abortion and higher taxes on alcohol consumption, leading to allegations that it is covertly undermining Turkish secularism. Some activists, commentators, opponents and government officials have accused the party of Islamism. The Justice and Development Party has faced two "closure cases" (attempts to officially ban the party, usually for Islamist practices) in 2002 and 2008.

Just 10 days before the national elections of 2002, Turkey's chief prosecutor, Sabih Kanadoğlu, asked the Turkish constitutional court to close the Justice and Development Party, which was leading in the polls at that time. The chief prosecutor charged the Justice and Development Party with abusing the law and justice. He based his case on the fact that the party's leader had been banned from political life for reading an Islamist poem, and thus the party had no standing in elections. The European Commission had previously criticized Turkey for banning the party's leader from participating in elections.[53]

The party again faced a closure trial in 2008 brought about by the lifting of a long-standing university ban on headscarves.[47] At an international press conference in Spain, Erdoğan answered a question of a journalist by saying, "What if the headscarf is a symbol? Even if it were a political symbol, does that give [one the] right to ban it? Could you bring prohibitions to symbols?" These statements led to a joint proposal of the Justice and Development Party and the far-right Nationalist Movement Party for changing the constitution and the law to lift a ban on women wearing headscarves at state universities. Soon afterwards, Turkey's chief prosecutor, Abdurrahman Yalçınkaya, asked the Constitutional Court of Turkey to close down the party on charges of violating the separation of religion and state in Turkey.[54] The closure request failed by only one vote, as only 6 of the 11 judges ruled in favor, with 7 required; however, 10 out of 11 judges agreed that the Justice and Development Party had become "a center for anti-secular activities", leading to a loss of 50% of the state funding for the party.[55]

Merger with People's Voice Party[]

In September 2012, two-year-old conservative-oriented People's Voice Party (HAS Parti) dissolved itself and joined the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) with a majority of its delegates' votes.[56] In July 2012, following long-held speculation that former HSP leader Numan Kurtulmuş was on Prime Minister Erdoğan's mind as his possible successor as party head, Erdoğan personally proposed to Kurtulmuş the idea of merging the parties under the umbrella of the AKP.

Elections[]

The party has won pluralities in the six most recent legislative elections, those of 2002, 2007, 2011, June 2015, November 2015, and 2018. The party held a majority of seats for 13 years, but lost it in June 2015, only to regain it in the snap election of November 2015 but then lose it again in 2018. Its past electoral success has been mirrored in the three local elections held since the party's establishment, coming first in 2004, 2009 and 2014 respectively. However, the party lost most of Turkey's biggest cities including Istanbul and Ankara in 2019 local elections, which has been attributed to the Turkish economic crisis, accusations of authoritarianism, as well as alleged government inaction on the Syrian refugee crisis.[35][36]

2002 general elections[]

The AKP won a sweeping victory in the 2002 elections, which saw every party previously represented in the Grand National Assembly ejected from the chamber. In the process, it won a two-thirds majority of seats, becoming the first Turkish party in 11 years to win an outright majority. Erdoğan, as the leader of the biggest party in parliament, would have been normally given the task to form a cabinet. However, according to the Turkish Constitution Article 109 the Prime Ministers had to be also a representative of the Turkish Parliament. Erdoğan, who was banned from holding any political office after a 1994 incident in which he read a poem deemed pro-Islamist by judges, was therefore not. As a result, Gül became prime minister. It survived the crisis over the 2003 invasion of Iraq despite a massive back bench rebellion where over a hundred AKP MPs joined those of the opposition Republican People's Party (CHP) in parliament to prevent the government from allowing the United States to launch a Northern offensive in Iraq from Turkish territory. Later, Erdoğan's ban was lifted with the help of the CHP and Erdoğan became prime minister by being elected to the parliament after a by-election in Siirt.

The AKP has undertaken structural reforms, and during its rule Turkey has seen rapid growth and an end to its three decade long period of high inflation rates. Inflation had fallen to 8.8% by 2004.

Influential business publications such as The Economist consider the AKP's government the most successful in Turkey in decades.[57]

2004 local elections[]

In the local elections of 2004, the AKP won 42% of the votes, making inroads against the secular Republican People's Party (CHP) on the South and West Coasts, and against the Social Democratic People's Party, which is supported by some Kurds in the South-East of Turkey.

In January 2005, the AKP was admitted as an observer member in the European People's Party (EPP). However, it left the EPP to join the Alliance of European Conservatives and Reformists (AECR) in 2013.

2007 elections[]

On 14 April 2007, an estimated 300,000 people marched in Ankara to protest the possible candidacy of Erdoğan in the 2007 presidential election, afraid that if elected as president, he would alter the secular nature of the Turkish state.[58] Erdoğan announced on 24 April 2007 that the party had decided to nominate Abdullah Gül as the AKP candidate in the presidential election.[59] The protests continued over the next several weeks, with over one million reported at an 29 April rally in Istanbul,[60][61] tens of thousands reported at separate protests on 4 May in Manisa and Çanakkale,[62] and one million in İzmir on 13 May.[63]

Early parliamentary elections were called after the failure of the parties in parliament to agree on the next Turkish president. The opposition parties boycotted the parliamentary vote and deadlocked the election process. At the same time, Erdoğan claimed the failure to elect a president was a failure of the Turkish political system and proposed to modify the constitution.

The AKP achieved a significant victory in the rescheduled 22 July 2007 elections with 46.6% of the vote, translating into control of 341 of the 550 available parliamentary seats. Although the AKP received significantly more votes in 2007 than in 2002, the number of parliamentary seats they controlled decreased due to the rules of the Turkish electoral system. However, they retained a comfortable ruling majority.[41]

Nationally, the elections of 2007 saw a major advance for the AKP, with the party outpolling the pro-Kurdish Democratic Society Party in traditional Kurdish strongholds such as Van and Mardin, as well as outpolling the secular-left CHP in traditionally secular areas such as Antalya and Artvin. Overall, the AKP secured a plurality of votes in 68 of Turkey's 81 provinces, with its strongest vote of 71% coming from Bingöl. Its weakest vote, a mere 12%, came from Tunceli, the only Turkish province where the Alevi form a majority.[64] Abdullah Gül was elected as the President in late August with 339 votes in the third round – the first at which a simple majority is required – after deadlock in the first two rounds, in which a two-thirds majority was needed.

2007 constitutional referendum[]

After the opposition parties deadlocked the 2007 presidential election by boycotting the parliament, the ruling AKP proposed a constitutional reform package. The reform package was first vetoed by President Sezer. Then he applied to the Turkish constitutional court about the reform package, because the president is unable to veto amendments for the second time. The court did not find any problems in the package and 69% of the voters supported the constitutional changes.

The reforms consisted of:

- electing the president by popular vote instead of by parliament;

- reducing the presidential term from seven years to five;

- allowing the president to stand for re-election for a second term;

- holding general elections every four years instead of five;

- reducing the quorum of lawmakers needed for parliamentary decisions from 367 to 184.

2009 local elections[]

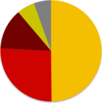

The Turkish local elections of 2009 took place during the financial crisis of 2007–2010. After the success of the AKP in the 2007 general elections, the party saw a decline in the local elections of 2009. In these elections the AKP received 39% of the vote, 3% less than in the local elections of 2004. Still, the AKP remained the dominating party in Turkey. The second party CHP received 23% of the vote and the third party MHP received 16% of the vote. The AKP won in Turkey's largest cities: Ankara and Istanbul.[65]

2010 constitutional referendum[]

Reforming the Constitution was one of the main pledges of the AKP during the 2007 election campaign. The main opposition party CHP was not interested in altering the Constitution on a big scale, making it impossible to form a Constitutional Commission (Anayasa Uzlaşma Komisyonu).[66] The amendments lacked the two-thirds majority needed to instantly become law, but secured 336 votes in the 550 seat parliament – enough to put the proposals to a referendum. The reform package included a number of issues: such as the right of individuals to appeal to the highest court, the creation of the ombudsman's office, the possibility to negotiate a nationwide labour contract, positive exceptions for female citizens, the ability of civilian courts to convict members of the military, the right of civil servants to go on strike, a privacy law, and the structure of the Constitutional Court. The referendum was agreed by a majority of 58%.

2014 elections[]

In the presidential election of 2014, the AKP's long time leader Recep Tayyip Erdoğan was elected president. In the party's first extraordinary congress, former foreign minister Ahmet Davutoğlu was unanimously elected unopposed as party leader and took over as Prime Minister on 28 August 2014. Davutoğlu stepped down as Prime Minister on 4 May 2016 following policy disagreements with President Erdoğan. Presidential aide Cemil Ertem said to Turkish TV that the country and its economy would stabilize further "when a prime minister more closely aligned with President Erdoğan takes office".[67]

2015 general election[]

In the general election held on 7 June, the AKP gained 40.87% of the vote and 258 seats in the Grand National Assembly of Turkey (Turkish: Türkiye Büyük Millet Meclisi, TBMM). Though it still remains the biggest party in Turkey, the AKP lost its status as the majority party and the power to form a single-party government. Until then it had held this majority without interruption for 13 years since it had come to power in 2002. Also, in this election, the AKP was pushing to gain 330 seats in the Grand National Assembly so that it could put a series of constitutional changes to a referendum, one of them was to switch Turkey from the current parliamentary government to an American-style executive presidency government. This pursuit met with a series of oppositions and criticism from the opposition parties and their supporters, fearing the measure would give more unchecked power to the current President of Turkey Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, who has drawn fierce criticisms both from home and abroad for his active role in the election, abandoning the traditional presidential role of maintaining a more neutral and impartial position in elections by his predecessors in the office. The result of the Kurdish issues-centered Peoples' Democratic Party, HDP, breaking through the 10% threshold to achieve 13.12% out of the total votes cast and gaining 80 seats in the Grand National Assembly in the election, which caused the AKP to lose its parliamentary majority.

2019 local elections[]

In the 2019 local elections, the ruling party AKP lost control of Istanbul and Ankara for the first time in 15 years, as well as 5 of Turkey's 6 largest cities. The loss has been widely attributed to AKP's mismanagement of the Turkish economic crisis, rising authoritarianism as well as alleged government inaction on the Syrian refugee crisis.[35][36] Soon after the elections, the Turkish government ordered a re-election in Istanbul. The decision led to a downfall on AKP's popularity and it lost the elections again in June with an even greater margin.[68][69][70][71] The result was seen as a huge blow to Erdoğan, who had once said that if his party 'lost Istanbul, we would lose Turkey.'[72] The opposition's landslide was characterized as the 'beginning of the end' for Erdoğan,[73][74][75] with international commentators calling the re-run a huge government miscalculation that can lead to a potential İmamoğlu candidacy in the next scheduled presidential election.[73][75] It is suspected that the scale of the government's defeat could provoke a cabinet reshuffle and early general elections, currently scheduled for June 2023.[76][77]

The AKP throughout 2020 and 2021 lost almost all support from Kurds, largely due to Erdogan's policy on the PKK and increasing Turkish nationalism, The AKP has attempted to regain support by implementing various centralized polices.[78]

Ideology and policies[]

Although the party is described as an Islamist party in some media, party officials reject those claims.[79] According to former minister Hüseyin Çelik, "In the Western press, when the AKP administration – the ruling party of the Turkish Republic – is being named, unfortunately most of the time 'Islamic,' 'Islamist,' 'mildly Islamist,' 'Islamic-oriented,' 'Islamic-based' or 'with an Islamic agenda,' and similar language is being used. These characterizations do not reflect the truth, and they sadden us." Çelik added, "The AKP is a conservative democratic party. The AKP's conservatism is limited to moral and social issues."[80] Also in a separate speech made in 2005, Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan stated, "We are not an Islamic party, and we also refuse labels such as Muslim-democrat." Erdoğan went on to say that the AKP's agenda is limited to "conservative democracy".[81]

On the other hand, according to at least one observer (Mustafa Akyol), under the AKP government of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, starting in 2007, "hundreds of secularist officers and their civilian allies" were jailed, and by 2012 the "old secularist guard" in positions of authority was replaced by members/supporters of the AKP and the Islamic Gülen movement.[82] On 25 April 2016, the Turkish Parliament Speaker İsmail Kahraman told a conference of Islamic scholars and writers in Istanbul that "secularism would not have a place in a new constitution”, as Turkey is “a Muslim country and so we should have a religious constitution". (One of the duties of Parliament Speaker is to pen a new draft constitution for Turkey.)[83]

In recent years, the ideology of the party has shifted more towards Turkish nationalism,[84][85] causing liberals such as Ali Babacan and some conservatives such as Ahmet Davutoğlu and Abdullah Gül to leave the party.[86]

The party's foreign policy has also been widely described as Neo-Ottomanist,[87] an ideology that promotes renewed Turkish political engagement in the former territories of its predecessor state, the Ottoman Empire. However, the party's leadership has also rejected this label.[88] The party's relationship with the Muslim Brotherhood has drawn allegations of Islamism.[38]

The AKP favors a strong centralized leadership, having long advocated for a presidential system of government and significantly reduced the number of elected local government positions in 2013.[50]

The party was an observer in the center-right European People's Party between 2005 and 2013 and a member of the Eurosceptic Alliance of Conservatives and Reformists in Europe (ACRE) from 2013[89] to 2018.[90]

European affiliation[]

In 2005, the party was granted observer membership in the European People's Party (EPP).

In November 2013, the party left the EPP to join the Alliance of European Conservatives and Reformists (now European Conservatives and Reformists Party) instead.[91] This move was attributed to the AKP's disappointment to not to be granted full membership in the EPP, while it was admitted as a full member of the AECR.[92] It drew criticism in both national and European discourses, as the driving force of Turkey's aspirations to become a member of the European Union decided to join a largely eurosceptic alliance, abandoning the more influential pro-European EPP, feeding suspicions that AKP wants to join a watered down, not a closely integrated EU.[93] The AKP withdrew from AECR in 2018.

Legislation and positions[]

From 2002 to 2011 the party passed series of reforms to increase accessibility to healthcare and housing, distribute food subsidies, increased funding for students, improved infrastructure in poorer districts, and improved rights for religious and ethnic minorities. AKP is also widely accredited for overcoming the 2001 economic crisis in Turkey by following International Monetary Fund guidelines, as well as successfully weathering the 2008 financial crisis. From 2002 to 2011 the Turkish economy grew on average by 7.5 percent annually, thanks to lower inflation and interest rates. The government under AKP also backed extensive privatization programs. The average income in Turkey rose from $2,800 U.S. in 2001 to around $10,000 U.S. in 2011, higher than income in some of the new EU member states. Other reforms included increasing civilian representation over military in areas of national security, education and media, and grant broadcasting and increased cultural rights to Kurds. On Cyprus, AKP supported unification of Cyprus, something deeply opposed by the Turkish military. Other AKP reforms included lifting bans on religious and conservative dress, such as headscarves, in universities and public institutions. AKP also ended discrimination against students from religious high schools, who previously had to meet additional criteria in areas of education and upon entry to universities. AKP is also accredited for bringing the Turkish military under civilian rule, a paradigm shift for a country that had experienced constant military meddling for almost a century.[81]

More recently, nationwide protests broke out against the alleged authoritarianism of the AKP in 2013, with the party's perceived heavy-handed response receiving western condemnation and stalling the party's once championed EU accession negotiations.[48] In addition to its alleged attempts to promote Islamism, the party is accused by some of restricting some civil liberties and internet use in Turkey, having temporarily blocked access to Twitter and YouTube in March 2014.[51] Especially after the government corruption scandal involving several AKP ministers in 2013, the party has been increasingly accused of crony capitalism.[49] The AKP favors a strong centralized leadership, having long advocated for a presidential system of government and significantly reduced the number of elected local government positions in 2013.[94]

Criticism[]

Critics have accused the AKP of having a 'hidden agenda' despite their public endorsement of secularism and the party maintains informal relations and support for the Muslim Brotherhood.[38] Both the party's domestic and foreign policy has been perceived to be Pan-Islamist or Neo-Ottoman, advocating a revival of Ottoman culture often at the expense of secular republican principles,[95] while increasing regional presence in former Ottoman territories.[14][96][97]

The AKP has been criticized for supporting a wide-scale purge of thousands of academics after the failed coup attempt in 2016. Primary, lower secondary and secondary school students were forced to spend the first day of school after the failed coup d'état watching videos about the ‘triumph of democracy’ over the plotters, and listening to speeches equating the civilian counter-coup that aborted the takeover with historic Ottoman victories going back 1000 years. Campaigns have been organised to release higher education personnel and to drop charges against them for peaceful exercise of academic freedom.[98]

Imprisonment of political activists continues, while the chair of Amnesty Turkey has been jailed for standing up to the AKP on trumped up "terrorist charges". These charges have drawn condemnation from many western countries, including from the US State Department, the EU, as well as from international and domestic human rights organisations.[99]

Party leaders[]

| No. | Portrait | Leader (birth–death) |

Constituency | Took office | Left office | Term length | Leadership elections |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Recep Tayyip Erdoğan (born 1954) | Siirt (2003) İstanbul (I) (2007, 2011) | 14 August 2001 | 27 August 2014 | 13 years, 13 days | 2006 Ordinary Congress 2009 Ordinary Congress 2012 Ordinary Congress | |

| 2 | Ahmet Davutoğlu (born 1959) | Konya | 27 August 2014 | 22 May 2016 | 1 year, 269 days | 2014 Extraordinary Congress 2015 Ordinary Congress | |

| 3 | Binali Yıldırım (born 1955) | İstanbul (I) (2002) Erzincan (2007) İzmir (II) (2011) İzmir (I) (Nov 2015) | 22 May 2016 | 21 May 2017 | 364 days | 2016 Extraordinary Congress | |

| (1) | Recep Tayyip Erdoğan (born 1954) | Incumbent President | 21 May 2017 | Incumbent | 4 years, 104 days | 2017 Extraordinary Congress 2018 Ordinary Congress |

Election results[]

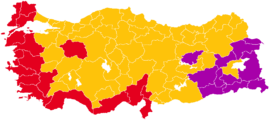

Presidential elections[]

| Presidential election record of the Justice and Development Party (AKP) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Election | Candidate | First round | Second round | Outcome | Map | |||||

| Votes | % | Votes | % | |||||||

| 10 August 2014 |  Recep Tayyip Erdoğan |

21,000,143 | 51.79% | N/A | N/A | Erdoğan elected |

| |||

| 24 June 2018 |  Recep Tayyip Erdoğan |

26,324,482 | 52.59% | N/A | N/A | Erdoğan elected |

| |||

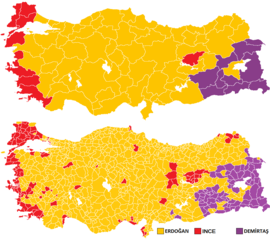

General elections[]

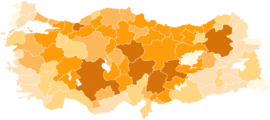

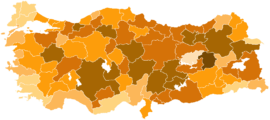

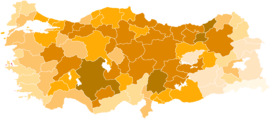

| General election record of the Justice and Development Party (AKP) 0–10% 10–20% 20–30% 30–40% 40–50% 50–60% 60–70% 70–80% | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Election | Leader | Vote | Seats | Result | Outcome | Map | ||||

| 3 November 2002 |  Recep Tayyip Erdoğan |

10,808,229 |

363 / 550 ( |

34.28% |

#1st AKP majority |

| ||||

| 22 July 2007 |  16,327,291 |

341 / 550 ( |

46.58% |

#1st AKP majority |

| |||||

| 12 June 2011 |  21,399,082 |

327 / 550 ( |

49.83% |

#1st AKP majority |

| |||||

| 7 June 2015 |  Ahmet Davutoğlu |

18,867,411 |

258 / 550 ( |

40.87% |

#1st Hung parliament |

| ||||

| 1 November 2015 |  23,681,926 |

317 / 550 ( |

49.50% |

#1st AKP majority |

| |||||

| 24 June 2018 |  Recep Tayyip Erdoğan |

21,333,172 |

295 / 600 ( |

42.56% |

#1st AKP-MHP Majority |

| ||||

Local elections[]

| Local election record of the Justice and Development Party (AKP) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Election | Metropolitan | District | Municipal | Provincial | Map | ||||||

| Vote | Mayors | Vote | Mayors | Vote | Councillors | Vote | Councillors | ||||

| 28 March 2004 | 46.07% 4,822,636 |

12 / 16 |

40.19% 9,674,306 |

1,750 / 3,193 |

40.33% 9,635,145 |

16,637 / 34,477 |

41.67% 13,447,287 |

2,276 / 3,208 |

| ||

| 29 March 2009 | 42.19% 7,672,280 |

10 / 16 |

38.64% 12,449,187 |

1,442 / 2,903 |

38.16% 12,237,325 |

14,732 / 32,393 |

38.39% 15,353,553 |

1,889 / 3,281 |

| ||

| 30 March 2014 | 45.54% 15,898,025 |

18 / 30 |

43.13% 17,952,504 |

800 / 1,351 |

42.87% 17,802,976 |

10,530 / 20,500 |

45.43% 4,622,484 |

779 / 1,251 |

| ||

| 31 March 2019 | 44.29% 16,000,992 |

15 / 30 |

42.55% 18,368,421 |

762 / 1,351 |

42.56% 18,299,576 |

10,175 / 20,500 |

41.61% 4,371,692 |

757 / 1,251 |

| ||

Referendums[]

| Election date | Party leader | Yes vote | Percentage | No vote | Percentage | AKP's support |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 21 October 2007 | Recep Tayyip Erdoğan | 19,422,714 | 68.95 | 8,744,947 | 31.05 | Yes |

| 12 September 2010 | Recep Tayyip Erdoğan | 21,789,180 | 57.88 | 15,854,113 | 42.12 | Yes |

| 16 April 2017 | Binali Yıldırım | 25,157,025 | 51.41 | 23,777,091 | 48.59 | Yes |

Footnotes[]

- ^† "AK PARTİ" (in all capital letters) is the self-declared abbreviation of the name of the party, as stated in Article 3 of the party charter,[100] while "AKP" is mostly preferred by its opponents; the supporters prefer "AK PARTİ" since the word "ak" in Turkish means "white", "clean", or "unblemished," lending a positive impression.[101] The Chief Public Prosecutor of the Supreme Court of Appeals initially used "AKP", but after an objection from the party,[102] "AKP" was replaced with "Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi" (without abbreviation) in documents.

Literature[]

- Cizre, Ümit, ed. (2008). Secular and Islamic politics in Turkey: The making of the Justice and Development Party. Routledge.

- Cizre, Ümit (2012). "A New Politics of Engagement: The Turkish Military, Society and the AKP". Democracy, Islam, and Secularism in Turkey.

- Hale, William; Özbudun, Ergun (2010). Islamism, Democracy and Liberalism in Turkey: The Case of the AKP. Routledge.

- Yavuz, M. Hakan, ed. (2006). The Emergence of a New Turkey: Islam, Democracy and the AK Parti. The University of Utah Press.

- Yavuz, M. Hakan (2009). Secularism and Muslim Democracy in Turkey. Cambridge University Press.

See also[]

- 2013 corruption scandal in Turkey

- Democrat Party (Turkey, 1946–1961)

- Conservative democracy

- Fidesz

- Gezi Park protests

- Law and Justice

- Nationalist Movement Party

- Republican People's Party (Turkey)

References[]

- ^ "AK PARTİ" (in Turkish). yargitaycb.gov.tr. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- ^ Hüseyin Şengül. "AKP mi, AK Parti mi?" (in Turkish). bianet.org. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- ^ "Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi" (in Turkish). Yargıtay Cumhuriyet Başsavcılığı. Retrieved 1 April 2021.

- ^ "The AK Party's Islamic Realist Political Vision: Theory and Practice". June 2014.

- ^ Çağliyan‐i̇Çener, Zeyneb (December 2009). "The Justice and Development Party's Conception of "Conservative Democracy": Invention or Reinterpretation?". Turkish Studies. 10 (4): 595–612. doi:10.1080/14683840903384851. hdl:11693/22548. S2CID 53443926.

- ^ "Erdogan faces serious setbacks in Turkish local elections". April 2019.

- ^ "AKP yet to win over wary business elite". Financial Times. 8 July 2007.

- ^ Cagaptay, Soner (2014). The Rise of Turkey. Potomac Books. p. 117.

- ^ Yavuz, M. Hakan (2009). Secularism and Muslim Democracy in Turkey. Cambridge University Press. p. 105.

- ^ "Erdoğan's Triumph". Financial Times. 24 July 2007.

The AKP is now a national conservative party — albeit rebalancing power away from the westernised urban elite and towards Turkey's traditional heartland of Anatolia — as well as the Muslim equivalent of Europe's Christian Democrats.

[permanent dead link] - ^ Abbas, Tahir (2016). Contemporary Turkey in Conflict. Edinburgh University Press.

- ^ Bayat, Asef (2013). Post-Islamism. Oxford University Press. p. 11.

- ^ Gunes, Cengiz; Zeydanlioglu, Welat, eds. (2013). The Kurdish Question in Turkey. Routledge. p. 270.

Konak, Nahide (2015). Waves of Social Movement Mobilizations in the Twenty-First Century: Challenges to the Neo-Liberal World Order and Democracy. Lexington Books. p. 64.

Jones, Jeremy (2007). Negotiating Change: The New Politics of the Middle East. I.B. Tauris. p. 219. - ^ Jump up to: a b Osman Rifat Ibrahim. "AKP and the great neo-Ottoman travesty". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 7 June 2015.

- ^ Yavuz, M. Hakan (1998). "Turkish identity and foreign policy in flux: The rise of Neo‐Ottomanism". Critique: Critical Middle Eastern Studies. 7 (12): 19–41. doi:10.1080/10669929808720119.

- ^ Kardaş, Şaban (2010). "Turkey: Redrawing the Middle East Map or Building Sandcastles?". Middle East Policy. 17: 115–136. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4967.2010.00430.x.

- ^ Borger, Julian (26 October 2020). "Republicans closely resemble autocratic parties in Hungary and Turkey – study". The Guardian. Retrieved 7 February 2020.

- ^ "Erdogan: The World's Newest Strongman". Bloomberg News. 25 June 2018.

- ^ "Trump tariffs, sanctions offer Erdogan excuse for Turkey's economic woes". NBC News. 23 September 2018.

- ^ Yilmaz, Ihsan; Bashirov, Galib (July 2017). "The AKP after 15 years: emergence of Erdoganism in Turkey". Third World Quarterly. 39 (9): 1812–1830. doi:10.1080/01436597.2018.1447371.

- ^ Baris Gulmez, Seckin (February 2013). "Rising euroscepticism in Turkish politics: The cases of the AKP and the CHP". Acta Politica. 48 (3): 326–344. doi:10.1057/ap.2013.2. S2CID 189929924.

- ^ Gülmez, Seçkin Barış (April 2020). "Rethinking Euroscepticism in Turkey: Government, Opposition and Public Opinion". Ekonomi, Politika & Finans Araştırmaları Dergisi. 5 (1): 1–22. doi:10.30784/epfad.684764.

- ^ Kastoryano, Riva (2013). Turkey between Nationalism and Globalization. Routledge. p. 97.

- ^ Cizre, Umit (2008). Secular and Islamic Politics in Turkey. Routledge. p. 50.

- ^ Picq, Manuela (2015). Sexualities in World Politics. Routledge. p. 126.

- ^ Bugra, Ayse (2014). New Capitalism in Turkey: The Relationship between Politics, Religion and Business. Edward Elgar Publishing. p. 49.

- ^ Yesilada, Birol (2013). Islamization of Turkey under the AKP Rule. Routledge. p. 63.

- ^ Guerin, Selen Sarisoy (2011). On the Road to EU Membership: The Economic Transformation of Turkey. Brussels University Press. p. 63.

- ^ Bugra, Ayse (2014). New Capitalism in Turkey: The Relationship between Politics, Religion and Business. Edward Elgar Publishing. p. 60.

- ^ Soner Cagaptay (17 October 2015). "Turkey's divisions are so deep they threaten its future". Guardian. Retrieved 27 December 2015.

- ^ Erisen, Cengiz (2016). Political Psychology of Turkish Political Behavior. Routledge. p. 102.

- ^ Çınar, Alev (2011). "The Justice and Development Party: Turkey's Experience with Islam, Democracy, Liberalism, and Secularism". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 43 (3): 529–541. doi:10.1017/S0020743811000651. hdl:11693/38147. ISSN 0020-7438. JSTOR 23017316. S2CID 155939308.

- ^ Coşar, Simten; Özman, Aylin (2004). "Centre-right politics in Turkey after the November 2002 general election: Neo-liberalism with a Muslim face". Contemporary Politics. 10: 57–74. doi:10.1080/13569770410001701233. S2CID 143771719.

- ^ "Turkey | Location, Geography, People, Economy, Culture, & History".

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Isil Sariyuce and Ivana Kottasová (23 June 2019). "Istanbul election rerun won by opposition, in blow to Erdogan". CNN. Retrieved 20 August 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Gall, Carlotta (23 June 2019). "Turkey's President Suffers Stinging Defeat in Istanbul Election Redo". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 20 August 2019.

- ^ GlobalSecurity.org – Reliable Security Information. "Justice and Development Party (AKP) Adalet ve Kalkinma Parti (AKP)". GlobalSecurity.org – Reliable Security Information. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

Others suggest that that around 60 percent of AKP's supporters were traditional (non-Islamist) conservatives, around 15 percent were Islamist-oriented voters, with the rest mostly swing protest voters upset with corruption in the other parties.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Turkey: AKP's Hidden Agenda or a Different Vision of Secularism?". Nouvelle Europe. 7 April 2011. Retrieved 7 June 2015."The "Hidden" That Never Was". Reflections Turkey. Retrieved 7 June 2015.[permanent dead link]

"Support for Muslim Brotherhood isolates Turkey". Die Weld. Retrieved 7 June 2015.Ömer Taşpınar (1 April 2012). "Islamist Politics in Turkey: The New Model?". The Brookings Institution. Retrieved 7 June 2015. - ^ "What you should know about Turkey's AKP-Gulen conflict". Al-Monitor. 3 January 2014. Archived from the original on 24 April 2015. Retrieved 7 June 2015.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 November 2013. Retrieved 2 June 2013.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ Jump up to: a b "New to Turkish politics? Here's a rough primer". Turkish Daily News. 22 July 2007. Archived from the original on 8 July 2012. Retrieved 22 July 2008.

- ^ Jakes, Lara (9 December 2020). "U.S. Takes Tougher Tone With Turkey as Trump Exits". New York Times. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- ^ "Turkey: Erdogan faces new protests over corruption scandal". Digital Journal. 28 December 2013. Retrieved 31 December 2013.

- ^ "İstanbul'da yolsuzluk ve rüşvet operasyonu". 17 December 2013.

- ^ "Turkey officially designates Gulen religious group as terrorists". Reuters. 31 May 2016. Retrieved 31 May 2016.

- ^ "Turkey: The New Model?". 30 November 2001.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Robert Tait (30 July 2008). "Turkey's governing party avoids being shut down for anti-secularism". The Guardian. Retrieved 7 June 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "EU delays Turkey membership talks after German pressure". BBC News. 25 June 2013. Retrieved 7 June 2015.

"Gezi Park protests: The AKP's battle with Turkish society". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 7 June 2015. - ^ Jump up to: a b "New Turkey and AKP-type capitalism". Today's Zaman. 24 September 2014. Retrieved 7 June 2015.

"Mass Murder in Soma Mine: Crony Capitalism and Fetish of Growth in Turkey". politiikasta.fi. Retrieved 7 June 2015. - ^ Jump up to: a b Babacan, Nuray (30 January 2015). "Presidential system tops AKP's election campaign". Hurriet Daily News. Retrieved 7 June 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kevin Rawlinson (21 March 2014). "Turkey blocks use of Twitter after prime minister attacks social media site". The Guardian. Retrieved 7 June 2015.

"Turkey moves to block YouTube access after 'audio leak'". BBC News. 27 March 2014. Retrieved 7 June 2015.

"Turkey: What's Behind the AKP's New Anti-Abortion Agenda?". EurasiaNet.org. Retrieved 7 June 2015.

Jenna Krajeski (14 February 2014). "The Last Chance To Stop Turkey's Harsh New Internet Law". The New Yorker. Retrieved 7 June 2015.

"AKP Wages Jihad Against Alcohol in Turkey". Al-Monitor. 23 May 2013. Retrieved 7 June 2015. - ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 17 March 2012. Retrieved 24 March 2011.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ "Turkey mulls banning leading party before elections". EurActiv. 23 October 2002. Retrieved 15 February 2011.

- ^ Gungor, Izgi (22 July 2008). "From landmark success to closure: AKP's journey". Turkish Daily News. Retrieved 11 August 2008.[permanent dead link]

"Closure case against ruling party creates shockwaves". Today's Zaman. 15 March 2008. Archived from the original on 21 April 2008. Retrieved 16 November 2008.

"Full text of testimony". Milliyet (in Turkish). Archived from the original on 12 May 2011. Retrieved 4 September 2008. - ^ Today's Zaman, 19 August 2013, AKP to ask for retrial by Constitutional Court Archived 20 August 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "HSP dissolves itself as its leader plans to join the ruling party". Hurriet Daily News. Retrieved 7 June 2015.

- ^ "The battle for Turkey's soul (Democracy v secularism in Turkey)". The Economist. 3 May 2007. Archived from the original on 12 August 2018. Retrieved 22 July 2008.

- ^ "Secular rally targets Turkish PM," BBC News, 14 April 2007.

- ^ "Turkey's ruling party announces FM Gul as presidential candidate," Xinhua, 24 April 2007.

- ^ "More than one million rally in Turkey for secularism, democracy". Agence France-Presse. Retrieved 29 April 2007.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "One million Turks rally against government". Reuters. 29 April 2007. Retrieved 30 April 2007.

- ^ "Saylan: Manisa mitingi önemli". Milliyet (in Turkish). Retrieved 4 May 2007.

- ^ "Turks protest ahead of early elections". Swissinfo. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 13 May 2007.

- ^ "Turkey: 22 July 2007 – Election Results". BBC Turkish. 23 July 2007. Retrieved 22 July 2008.

- ^ "Turkish local elections, 2009". International / Europe. NTV-MSNBC. 29 March 2009. Archived from the original on 29 March 2009. Retrieved 29 March 2009.

- ^ "AKP'nin Anayasa hedefi 15 madde". NTVMSNBC. 17 February 2009. Retrieved 17 February 2009.

- ^ "Turkey PM Ahmet Davutoğlu to quit amid reports of Erdoğan rift". BBC News. BBC. 5 May 2016. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ^ "Turkey's ruling party loses Istanbul election". BBC News. 23 June 2019.

- ^ Isil Sariyuce and Ivana Kottasová (23 June 2019). "Istanbul election rerun set to be won by opposition, in blow to Erdogan". CNN.

- ^ Gauthier-Villars, David (23 June 2019). "In Setback for Erdogan, Opposition Candidate Wins Istanbul Mayor Seat". Wall Street Journal.

- ^ "Son dakika… Financial Times'tan şok İstanbul seçimi yorumu". www.sozcu.com.tr.

- ^ "Erdoğan: 'İstanbul'da teklersek, Türkiye'de tökezleriz'". Tele1. 2 April 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Lowen, Mark (24 June 2019). "Can Erdogan bounce back from big Turkey defeat?". Retrieved 6 August 2019.

- ^ "The beginning of the end for Erdogan?". The National. Retrieved 6 August 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Could Imamoglu victory in Istanbul be 'beginning of the end' for Erdogan?". euronews. 24 June 2019. Retrieved 6 August 2019.

- ^ Ellyatt, Holly (24 June 2019). "Turkey's Erdogan suffers election blow, sparking hope for change". CNBC.

- ^ Gall, Carlotta (23 June 2019). "Turkey's President Suffers Stinging Defeat in Istanbul Election Redo". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 6 August 2019.

- ^ Zaman, Amberin (15 March 2021). "Erdogan's Islamic credentials no longer a winning hand among Turkey's Kurds". Al-Monitor.

- ^ "Justice and Development Party". Encyclopædia Britannica. Britannica.com. Retrieved 21 July 2014.

Unlike its predecessors, the AKP did not centre its image around an Islamic identity; indeed, its leaders underscored that it was not an Islamist party and emphasized that its focus was democratization, not the politicization of religion.

- ^ "AKP explains charter changes, slams foreign descriptions". Hürriyet Daily News. Istanbul. 28 March 2010. Retrieved 21 July 2014.

In the Western press, when the AKP administration, the ruling party of the Turkish Republic, is being named, unfortunately most of the time Islamic agenda,' and similar language is being used. These characterizations do not reflect the truth, and they sadden us," Çelik said. "Yes, the AKP is a conservative democratic party. The AKP's conservatism is limited to moral and social issues.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Taşpınar, Ömer (24 April 2012). Turkey: The New Model?. Brookings Institution (Report).

- ^ Akyol, Mustafa (22 July 2016). "Who Was Behind the Coup Attempt in Turkey?". New York Times. Retrieved 23 July 2016.

- ^ "Secularism must be removed from constitution, Turkey's Parliament Speaker says". Milliyet. 27 April 2016. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- ^ "Erdogan The Nationalist Vs Erdogan The Islamist". Hoover Institution. 13 December 2018.

- ^ "Turkey's Hour of Nationalism: The Deeper Sources of Political Realignment". The American Interest. 18 June 2019.

- ^ "Turkish Conservatives' Loyalty to Erdoğan and Views on Potential Successors". Center for American Progress. 5 December 2019.

- ^ Taşpınar, Ömer (September 2008). "Turkey's Middle East Policies: Between Neo-Ottomanism and Kemalism". Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Retrieved 5 June 2010.

- ^ "I am not a neo-Ottoman, Davutoğlu says". Today's Zaman. Turkey. 25 November 2009. Archived from the original on 25 October 2013. Retrieved 9 January 2012.

- ^ "Erdoğan's AKP party joins Cameron's conservative political family". EURACTIV.com. 13 November 2013.

- ^ "Conservative Eurosceptic alliance reaches out to far-right". Financial Times. 12 November 2018.

- ^ "Erdoğan's AKP party joins Cameron's conservative political family". EurActiv. 13 November 2013. Retrieved 14 January 2015.

- ^ Lagendijk, Joost (12 November 2013). "AKP looking for new European friends". Today's Zaman. Archived from the original on 11 February 2015. Retrieved 14 January 2015.

- ^ Yinanç, Barçin (19 November 2013). "By abandoning conservatives AKP helps anti-Turkey bloc in EU". Hürriyet Daily News. Retrieved 14 January 2015.

- ^ "Presidential system tops AKP's election campaign". Hurriet Daily News. Retrieved 7 June 2015.

- ^ Öztürk, Ahmet Erdi (1 October 2016). "Turkey's Diyanet under AKP rule: from protector to imposer of state ideology?" (PDF). Southeast European and Black Sea Studies. 16 (4): 619–635. doi:10.1080/14683857.2016.1233663. ISSN 1468-3857. S2CID 151448076.

- ^ "Düşünmek Taraf Olmaktır". taraf.com.tr. Retrieved 7 June 2015.

- ^ "AKP'li vekil: Osmanlı'nın 90 yıllık reklam arası sona erdi". Cumhuriyet Gazetesi. 15 January 2015. Retrieved 7 June 2015.

"İslami Analiz". - ^ "Turkey's War Against the Academics". 30 June 2017.

- ^ "Taner Kılıç released on bail".

- ^ "AK PARTİ TÜZÜĞÜ" [AK PARTİ STATUTES] (PDF) (in Turkish). Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi. Retrieved 23 September 2014.

- ^ "Less than white?". The Economist. 18 September 2008. Retrieved 22 September 2008.

"AK Parti mi, AKP mi? (AK Parti or AKP?)". Habertürk (in Turkish). 5 June 2009. Retrieved 10 August 2009. - ^ Ebru Toktar and Ersin Bal. "Laiklik anlayışlarımız farklı" Archived 12 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine (in Turkish). Akşam, 7 May 2008.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Justice and Development Party. |

- Official website (in English and Turkish)

- AK Youth (in Turkish)

- AKP Political Academy (in Turkish)

- AK Kanal (in Turkish)

- AK İcraatlar (in Turkish)

- Justice and Development Party (Turkey)

- Political parties in Turkey