Kareem Abdul-Jabbar

Abdul-Jabbar in 2014 | |

| Personal information | |

|---|---|

| Born | April 16, 1947 New York City, New York |

| Nationality | American |

| Listed height | 7 ft 2 in (2.18 m) |

| Listed weight | 225 lb (102 kg) |

| Career information | |

| High school | Power Memorial (Manhattan, New York) |

| College | UCLA (1966–1969) |

| NBA draft | 1969 / Round: 1 / Pick: 1st overall |

| Selected by the Milwaukee Bucks | |

| Playing career | 1969–1989 |

| Position | Center |

| Number | 33 |

| Coaching career | 1998–2011 |

| Career history | |

| As player: | |

| 1969–1975 | Milwaukee Bucks |

| 1975–1989 | Los Angeles Lakers |

| As coach: | |

| 1998–1999 | Alchesay HS (assistant) |

| 2000 | Los Angeles Clippers (assistant) |

| 2002 | Oklahoma Storm |

| 2005–2011 | Los Angeles Lakers (assistant) |

| Career highlights and awards | |

As head coach:

As assistant coach:

| |

| Career NBA statistics | |

| Points | 38,387 (24.6 ppg) |

| Rebounds | 17,440 (11.2 rpg) |

| Assists | 5,660 (3.6 apg) |

| Stats | |

| Stats | |

| Basketball Hall of Fame as player | |

| College Basketball Hall of Fame Inducted in 2006 | |

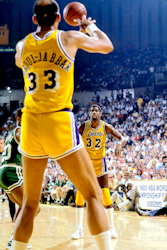

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar (born Ferdinand Lewis Alcindor Jr.; April 16, 1947) is an American former professional basketball player who played 20 seasons in the National Basketball Association (NBA) for the Milwaukee Bucks and the Los Angeles Lakers. During his career as a center, Abdul-Jabbar was a record six-time NBA Most Valuable Player (MVP), a record 19-time NBA All-Star, a 15-time All-NBA selection, and an 11-time NBA All-Defensive Team member. A member of six NBA championship teams as a player and two more as an assistant coach, Abdul-Jabbar twice was voted NBA Finals MVP. In 1996, he was honored as one of the 50 Greatest Players in NBA History. NBA coach Pat Riley and players Isiah Thomas and Julius Erving called him the greatest basketball player of all time.[1][2][3][4][5]

With him on the team, parochial high school Power Memorial, in New York City, won 71 consecutive basketball games. He was recruited by Jerry Norman, the assistant coach at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA),[6] where he played for coach John Wooden[7] on three consecutive national championship teams. He was a record three-time MVP of the NCAA Tournament. Drafted with the first overall pick by the one-season-old Bucks franchise in the 1969 NBA draft, Alcindor spent six seasons in Milwaukee. After leading the Bucks to its first NBA championship at age 24 in 1971, he took the Muslim name Kareem Abdul-Jabbar. Using his trademark "skyhook" shot, he established himself as one of the league's top scorers. In 1975, he was traded to the Lakers, with whom he played the final 14 seasons of his career in which they won five additional NBA championships. Abdul-Jabbar's contributions were a key component in the "Showtime" era of Lakers basketball. Over his 20-year NBA career, his teams succeeded in making the playoffs 18 times and got past the first round 14 times; his teams reached the NBA Finals on 10 occasions.

At the time of his retirement at age 42 in 1989, Abdul-Jabbar was the NBA's all-time leader in points scored (38,387), games played (1,560), minutes played (57,446), field goals made (15,837), field goal attempts (28,307), blocked shots (3,189), defensive rebounds (9,394), career wins (1,074), and personal fouls (4,657). He remains the all-time leader in points scored, field goals made, and career wins. He is ranked third all-time in both rebounds and blocked shots. ESPN named him the greatest center of all time in 2007,[8] the greatest player in college basketball history in 2008,[9] and the second best player in NBA history (behind Michael Jordan) in 2016.[10] Abdul-Jabbar has also been an actor, a basketball coach, a best-selling author,[11][12] and a martial artist, having trained in Jeet Kune Do under Bruce Lee and appeared in his film Game of Death (1972). In 2012, Abdul-Jabbar was selected by Secretary of State Hillary Clinton to be a U.S. global cultural ambassador.[13] In 2016, President Barack Obama awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom.[14]

Early life

Ferdinand Lewis Alcindor Jr. was born in New York City, the only child of Cora Lillian, a department store price checker, and Ferdinand Lewis Alcindor Sr., a transit police officer and jazz musician.[15][16] He grew up in the Dyckman Street projects in the Inwood neighborhood of Upper Manhattan.[17] At birth, Alcindor weighed 12 lb 11 oz (5.75 kg) and was 22+1⁄2 inches (57 cm) long.[18][19] He was always very tall for his age.[18] By age nine, he was already 5 ft 8 in (1.73 m) tall.[20] Alcindor was often depressed as a teenager because of the stares and comments about his height.[18] By the eighth grade (age 13–14), he had grown to 6 ft 8 in (2.03 m) and could already slam dunk a basketball.[20][21]

Alcindor began his record-breaking basketball accomplishments when he was in high school, where he led coach Jack Donohue's Power Memorial Academy team to three straight New York City Catholic championships, a 71-game winning streak, and a 79–2 overall record.[22] This earned him "The Tower from Power" nickname.[23] His 2,067 total points were a New York City high school record.[24] The team won the national high school boys basketball championship when Alcindor was in 10th and 11th grade and was runner-up his senior year.[23] He had a strained relationship in his final year with Donohue after the coach called him a nigger.[25]

College career

Now 7-foot-1-inch (2.16 m) tall, Alcindor was relegated to the freshman team in his first year at UCLA,[26][27] as freshman were ineligible to play varsity until 1972.[28] The freshman squad included fellow high school All-Americans Lucius Allen, Kenny Heitz and Lynn Shackelford.[29] On November 27, 1965, Alcindor made his first public performance in UCLA's annual varsity–freshman exhibition game, attended by 12,051 fans in the inaugural game at the Bruins' new Pauley Pavilion.[27][30][31] The 1965–66 varsity team was the two-time defending national champions and the top-ranked team in preseason polls.[27][32] The freshman team won 75–60 behind Alcindor's 31 points and 21 rebounds.[30][18] It was the first time a freshman team had beaten the UCLA varsity squad.[18] The varsity had lost Gail Goodrich and Keith Erickson from the championship squad to graduation, and starting guard Freddie Goss was out sick.[30][33] After the game, UPI wrote: "UCLA's Bruins open defense of their national basketball title this week, but right now they're only the second best team on campus."[33][34] The freshman team was 21–0 that year, dominating against junior college and other freshman teams.[32]

He made his varsity debut as a sophomore in 1966 and received national coverage: Sports Illustrated described him as "The New Superstar" after he scored 56 points in his first game, which broke the UCLA single-game record held by Gail Goodrich.[18][24][35] He averaged 29 points per game during the season and led UCLA to an undefeated 30–0 record and a national championship.[36] After the season, the dunk was banned in college basketball in an attempt to curtail his dominance.[22][36] The rule was not rescinded until the 1976–77 season.[37] Alcindor was the main contributor to the team's three-year record of 88 wins and only two losses: one to the University of Houston in which Alcindor had an eye injury, and the other to crosstown rival USC who played a "stall game";[27][38] there was no shot clock in that era, allowing the Trojans to hold the ball as long as it wanted before attempting to score. They limited Alcindor to only four shots and 10 points.[39]

During his college career, Alcindor was a three-time national player of the year (1967–1969); was a three-time unanimous first-team All-American (1967–1969); played on three NCAA basketball champion teams (1967, 1968 and 1969); was honored as the Most Outstanding Player in the NCAA Tournament three times and became the first-ever Naismith College Player of the Year in 1969.[40][41] He was the only player to win the Helms Foundation Player of the Year award three times.[42]

Alcindor had considered transferring to Michigan because of unfulfilled recruiting promises. UCLA player Willie Naulls introduced Alcindor and teammate Lucius Allen to athletic booster Sam Gilbert, who convinced the pair to remain at UCLA.[43]

During his junior year, Alcindor suffered a scratched left cornea on January 12, 1968, in a game against Cal when he was struck by Tom Henderson in a rebound battle.[44] He would miss the next two games against Stanford and Portland.[22] This happened right before the showdown game against Houston.[45] His cornea would again be scratched during his pro career, which subsequently caused him to wear goggles for eye protection.[46]

At the time, the NBA did not allow college underclassmen to declare early for the draft. He completed his studies and earned a Bachelor of Arts with a major in history in 1969. In his free time, he practiced martial arts. He studied aikido in New York between his sophomore and junior year, before learning Jeet Kune Do under Bruce Lee in Los Angeles.[47][48]

Game of the Century

On January 20, 1968, Alcindor and the UCLA Bruins faced coach Guy Lewis's Houston Cougars in the first-ever nationally televised regular-season college basketball game, with 52,693 in attendance at the Astrodome. Cougar forward Elvin Hayes scored 39 points and had 15 rebounds, while Alcindor, who suffered from a scratch on his left cornea, was held to just 15 points as Houston won 71–69. The Bruins' 47-game winning streak ended in what has been called the "Game of the Century".[49] Hayes and Alcindor had a rematch in the semi-finals of the NCAA Tournament, where UCLA, with a healthy Alcindor, defeated Houston 101–69 en route to the national championship. UCLA limited Hayes, who was averaging 37.7 points per game, to only ten points. Wooden credited his assistant, Jerry Norman, for devising the diamond-and-one defense that contained Hayes.[50][51] Sports Illustrated ran a cover story on the game and used the headline: "Lew's Revenge: The Rout of Houston."[52]

Conversion to Islam and 1968 Olympic boycott

During the summer of 1968, Alcindor took the shahada twice and converted to Sunni Islam from Catholicism. He adopted the Arabic name Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, though he did not begin using it publicly until 1971.[53] He boycotted the 1968 Summer Olympics by deciding not to try out for the United States Men's Olympic Basketball team, who went on to easily win the gold medal. Alcindor's decision to stay home during the 1968 Games was in protest of the unequal treatment of African-Americans in the United States.

An episode of Black Journal produced by WNET and broadcast on May 2, 1972, features Kareem Abdul Jabbar discussing his boycott of the 1968 Olympics to his practice of the Islamic religion.[54]

Though he denied any connection with the radical Nation of Islam, Jabbar was linked to them in a story that appeared in Sports Illustrated dated February 19, 1973, specifically to members of the group in Washington D.C..

School records

As of the 2019–2020 season, he still holds or shares a number of individual records at UCLA:[55][56]

- Highest career scoring average: 26.4

- Most career field goals: 943 (tied with Don MacLean)

- Most points in a season: 870 (1967)

- Highest season scoring average: 29.0 (1967)

- Most field goals in a season: 346 (1967) (also, the second most: 303 (1969), and third: 294 (1968))

- Most free throw attempts in a season: 274 (1967)

- Most points in a single game: 61

- Most field goals in a single game: 26 (vs. Washington State, February 25, 1967)

He is represented in the top ten in a number of other school records, including season and career rebounds, second only to Bill Walton.

Professional career

Milwaukee Bucks (1969–1975)

The Harlem Globetrotters offered Alcindor $1 million to play for them, but he declined and was picked first in the 1969 NBA draft by the Milwaukee Bucks, who were in only their second season of existence. The Bucks won a coin-toss with the Phoenix Suns for first pick. He was also chosen first overall in the 1969 American Basketball Association draft by the New York Nets.[57] The Nets believed that they had the upper hand in securing Alcindor's services because he was from New York; however, when Alcindor told both the Bucks and the Nets that he would accept only one offer from each team, the Nets bid too low. Sam Gilbert negotiated the contract along with Los Angeles businessman Ralph Shapiro at no charge.[43][58] After Alcindor chose the Milwaukee Bucks' offer of $1.4 million, the Nets offered a guaranteed $3.25 million. Alcindor declined the offer, saying, "A bidding war degrades the people involved. It would make me feel like a flesh peddler, and I don't want to think like that."[59]

Alcindor's presence enabled the 1969–70 Bucks to claim second place in the NBA's Eastern Division with a 56–26 record (improved from 27–55 the previous year). On February 21, 1970, he scored 51 points in a 140-127 win over the SuperSonics.[60] Alcindor was an instant star, ranking second in the league in scoring (28.8 ppg) and third in rebounding (14.5 rpg), for which he was awarded the title of NBA Rookie of the Year.[22] In the series-clinching game against the 76ers, he recorded 46 points and 25 rebounds.[61] With that, he joins Wilt Chamberlain as the only rookies to record at least 40 points and 25 rebounds in a playoff game in their rookie season.[citation needed] He also set an NBA rookie record with 10 or more games of 20+ points scored during the playoffs, tied by Jayson Tatum in 2018.[62]

The next season, the Bucks acquired All-Star guard Oscar Robertson. Milwaukee went on to record the best record in the league with 66 victories in the 1970–71 season,[22] including a then-record 20 straight wins.[63] Alcindor was awarded his first of six NBA Most Valuable Player Awards, along with his first scoring title (31.7 ppg).[22] He also led the league in total points, with 2,596.[24] The Bucks won the NBA title, sweeping the Baltimore Bullets 4–0 in the 1971 NBA Finals. Alcindor posted 27 points, 12 rebounds and seven assists in Game 4,[64] and he was named the Finals MVP after averaging 27 points per game on 60.5% shooting in the series.[65] During the offseason, Alcindor and Robertson joined Bucks head coach Larry Costello on a three-week basketball tour of Africa on behalf of the State Department. In a press conference at the State Department on June 3, 1971, he stated that going forward, he wanted to be called by his Muslim name, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar (Arabic: كريم عبد الجبار, Karīm Abd al-Jabbār), its translation roughly "noble one, servant of the Almighty [i.e., servant of Allah]".[66][67] He had converted to Islam while at UCLA.[24]

Abdul-Jabbar remained a dominant force for the Bucks. The following year, he repeated as scoring champion (34.8 ppg and 2,822 total points)[24] and became the first player to be named the NBA Most Valuable Player twice in his first three years.[68] In 1974, Abdul-Jabbar led the Bucks to their fourth consecutive Midwest Division title,[69] and he won his third MVP Award in four years.[70] He was among the top five NBA players in scoring (27.0 ppg, third), rebounding (14.5 rpg, fourth), blocked shots (283, second), and field goal percentage (.539, second).[69]

Robertson, who became a free agent in the offseason, retired in September 1974 after he was unable to agree on a contract with the Bucks.[71][72] On October 3, Abdul-Jabbar privately requested a trade to the New York Knicks, with his second choice being the Washington Bullets (now the Wizards) and his third, the Los Angeles Lakers.[73] He had never spoken negatively of the city of Milwaukee or its fans, but he said that being in the Midwest did not fit his cultural needs.[73][74][75] Two days later in a pre-season game before the 1974–75 season against the Boston Celtics in Buffalo, New York, Abdul-Jabbar caught a fingernail in his left eye from Don Nelson and suffered a corneal abrasion; this angered him enough to punch the backboard stanchion, breaking two bones his right hand.[73][76][77] He missed the first 16 games of the season, during which the Bucks were 3–13, and returned in late November wearing protective goggles.[77] On March 13, 1975, sportscaster Marv Albert reported that Abdul-Jabbar requested a trade to either New York or Los Angeles, preferably to the Knicks.[73][78] The following day after a loss in Milwaukee to the Lakers, Abdul-Jabbar confirmed to reporters his desire to play in another city.[79] He averaged 30.0 points during the season, but Milwaukee finished in last place in the division at 38–44.[80]

Los Angeles Lakers (1975–1989)

In 1975, the Lakers acquired Abdul-Jabbar and reserve center Walt Wesley from the Bucks for center Elmore Smith, guard Brian Winters, blue-chip rookies Dave Meyers and Junior Bridgeman, and cash.[73][80] In the 1975–76 season, his first with the Lakers, he had a dominating season, averaging 27.7 points per game and leading the league in rebounding (16.9), blocked shots (4.12), and total minutes played (3,379).[81][82] His 1,111 defensive rebounds remains the NBA single-season record (defensive rebounds were not recorded prior to the 1973–74 season).[83] He earned his fourth MVP award, becoming the first winner in Lakers' franchise history,[84] but missed the post-season for the second straight year as the Lakers finished 40–42.[85]

Afer acquiring a cast of no-name free agents, the Lakers were projected to finished near the bottom of the Pacific Division in 1976–77. However, Abdul-Jabbar helped lead the team to the best record (53–29) in the NBA. He won his fifth MVP award, tying Bill Russell's record. Abdul-Jabbar led the league in field goal percentage (.579), was third in scoring (26.2), and was second in rebounds (13.3) and blocked shots (3.18).[86] In the playoffs, the Lakers beat the Golden State Warriors in the Western Conference semi-finals, setting up a confrontation with the Portland Trail Blazers. The result was a memorable matchup, pitting Abdul-Jabbar against a young, injury-free Bill Walton. Although Abdul-Jabbar dominated the series statistically, Walton and the Trail Blazers (who were experiencing their first-ever run in the playoffs) swept the Lakers, behind Walton's skillful passing and timely plays.[87][88]

Two minutes into the opening game of the 1977–78 season, Abdul-Jabbar broke his right hand punching Milwaukee's Kent Benson in retaliation to the rookie's elbow to his stomach. Benson suffered a black right eye and required two stitches.[89][90][91] According to Benson, Abdul-Jabbar initiated the elbowing, but there were no witnesses and it was not captured on replays.[89][91] Abdul-Jabbar, who broke the same bone in 1975 after he punched the backboard support,[90] was out for almost two months and missed 20 games.[91][92] He was fined a then-league record $5,000 but was not suspended.[90][92] Benson missed one game but was not punished by the league.[91][93] The Lakers were 8–13 when Abdul-Jabbar returned.[94] He was not named to the 1978 NBA All-Star Game, the only time in his 20-year career he was not selected to an All-Star Game.[95] Chicago's Artis Gilmore and Detroit's Bob Lanier were chosen as reserves for the West, with Walton starting at center.[96] Amid criticism from the media over his performance, Abdul-Jabbar had 39 points, 20 rebounds, six assists and four blocks in a win over the Philadelphia 76ers the day the All-Star rosters were announced.[97] He added 37 points and 30 rebounds in a victory over the New Jersey Nets (now Brooklyn) in the final game before the All-Star break.[98]

Abdul-Jabbar's play remained strong during the next two seasons, being named to the All-NBA Second Team twice, the All-Defense First Team once, and the All-Defense Second Team once.[99] The Lakers, however, continued to be stymied in the playoffs, being eliminated by the Seattle SuperSonics in both 1978 (first round) and 1979 (semifinals).[100]

In 1979, the Lakers selected Magic Johnson with the first overall pick of the draft. They had acquired the pick from the New Orleans Jazz (later Utah) in 1976, when league rules required that they compensate Los Angeles for their signing of free agent Gail Goodrich.[101] The addition of Johnson paved the way for a Laker dynasty of the 1980s, appearing in the finals eight times and winning five NBA championships.[102] While less dominant than in his younger years, Abdul-Jabbar reinforced his status as one of the greatest basketball players ever,[102] adding an additional four All-NBA First Team selections and two All-Defense First Team honors.[99] He won his record sixth MVP award in 1980 and continued to average 20 or more points per game in the following six seasons. At age 38, he won his second Finals MVP in 1985.[102] On April 5, 1984, Abdul-Jabbar broke Chamberlain's record for most career points.[103] Later in his career, he bulked up to about 265 pounds (120 kg), to be able to withstand the strain of playing the highly physical center position into his early 40s.[citation needed]

While in Los Angeles, Abdul-Jabbar started doing yoga in 1976 to improve his flexibility, and was notable for his physical fitness regimen.[104] He says, "There is no way I could have played as long as I did without yoga."[105]

In 1983, Abdul-Jabbar's house burned down. Many of his belongings, including his beloved jazz LP collection of about 3,000 albums, were destroyed.[106] Many Lakers fans sent and brought him albums, which he found uplifting.[107]

The Lakers made the NBA Finals in each of Abdul-Jabbar's final three seasons, defeating Boston in 1987, and Detroit in 1988.[1] The Lakers lost to the Pistons in a four-game sweep in his final season.[108] After winning Game 7 of the 1988 finals, the 41-year-old Abdul-Jabbar announced in the locker room that he would return for one more season before retiring.[109][110] His points, rebounds, and minutes had dropped in his 19th season,[110][111][112] and there were reports prior to the game that he was retiring after the contest.[109][113] On his "retirement tour" he received standing ovations at games, both home and away, and gifts ranging from a yacht that said "Captain Skyhook" to framed jerseys from his career to a Persian rug.[114] In his biography My Life, Magic Johnson recalls that many Lakers and Celtics legends participated in Abdul-Jabbar's farewell game.[citation needed] At the Forum against Seattle in his final regular season game,[114] every Laker came onto the court wearing Abdul-Jabbar's trademark goggles and had to try a skyhook at least once, which led to comic results[citation needed].[115]

At the time of his retirement, Abdul-Jabbar held the record for most games played by a single player in the NBA;[116] this would later be broken by Robert Parish. He also was the all-time record holder for most points (38,387), most field goals made (15,837), and most minutes played (57,446).[24]

Post-NBA career

In 1995, Abdul-Jabbar began expressing an interest in coaching and imparting knowledge from his playing days.[117][118] His opportunities were limited despite the success he enjoyed during his playing days.[117] However, during his playing years, Abdul-Jabbar had developed a reputation for being introverted and sullen. He was often unfriendly with the media.[117][118][119] His sensitivity and shyness created a perception of him being aloof and surly.[117][120] At the time, his mentality was that he either did not have the time or did not owe anything to anyone.[121] Magic Johnson recalled as a kid being brushed off after asking him for an autograph. Abdul-Jabbar might freeze out a reporter if they touched him, and he once refused to stop reading the newspaper while giving an interview.[119]

Abdul-Jabbar believes that his repuation as a difficult person might have impacted his chances of being a head coach in the NBA or NCAA.[122] In his words, he said he had a mindset he could not overcome, and proceeded through his career oblivious to the effect his reticence might have on his future coaching prospects.[citation needed] Abdul-Jabbar said: "I didn't understand that I also had affected people that way and that's what it was all about. I always saw it like they were trying to pry. I was way too suspicious and I paid a price for it."[107]

Abdul-Jabbar worked as an assistant for the Los Angeles Clippers and the Seattle SuperSonics, helping mentor, among others, their young centers, Michael Olowokandi and Jerome James.[123] Abdul-Jabbar was the head coach of the Oklahoma Storm of the United States Basketball League in 2002, leading the team to the league's championship that season, but he failed to land the head coaching position at Columbia University a year later.[124] He then worked as a scout for the New York Knicks.[125] He returned to the Lakers as a special assistant coach to Phil Jackson for six seasons (2005–2011). Early on, he mentored their young center, Andrew Bynum.[126][127] Abdul-Jabbar also served as a volunteer coach at Alchesay High School on the Fort Apache Indian Reservation in Whiteriver, Arizona, in 1998.[128] He moved on from coaching in 2013 after unsuccessfully lobbying for open head coach positions with UCLA and the Milwaukee Bucks.[129]

In 2016, he performed a tribute to friend Muhammad Ali along with Chance the Rapper.[130]

Player profile

On offense, Abdul-Jabbar was a dominant low-post threat. In contrast to other low-post specialists like Wilt Chamberlain, Artis Gilmore or Shaquille O'Neal, Abdul-Jabbar was a relatively slender player, standing 7 ft 2 in (2.18 m) tall but weighing only 225 lb (102 kg) (though in his latter years the Lakers listed Abdul-Jabbar's weight as 265 pounds (120 kg)).[131][failed verification] However, he made up for his relative lack of bulk by showing textbook finesse,[citation needed] and was famous for his ambidextrous skyhook shot. It contributed to his high .559 field goal accuracy, making him the eighth-most accurate scorer of all time[132] and a feared clutch shooter. Abdul-Jabbar was also quick enough to run the Showtime fast break[citation needed] led by Magic Johnson and was well-conditioned, standing on the hardwood an average 36.8 minutes. In contrast to other big men, Abdul-Jabbar also could reasonably hit his free throws,[citation needed] finishing with a career 72% average.

Abdul-Jabbar maintained a dominant presence on defense. He was selected to the NBA All-Defensive Team eleven times. He frustrated opponents with his superior shot-blocking ability and denied an average of 2.6 shots a game. After the pounding he endured early in his career, his rebounding average fell to between six or eight a game in his latter years.[1]

As a teammate, Abdul-Jabbar exuded natural leadership and was affectionately called "Cap"[133] or "Captain" by his colleagues. He had an even temperament, which Riley said made him coachable.[134] A strict fitness regime made him one of the most durable players of all time.[citation needed] In the NBA, his 20 seasons and 1,560 games are performances surpassed only by former Celtics center Robert Parish.[135]

Abdul-Jabbar began wearing his trademark goggles after getting poked in the eye during preseason in 1975. He continued wearing them for years until abandoning them in the 1979 playoffs. He resumed wearing goggles in October 1980 after being accidentally poked in the right eye by Houston's Rudy Tomjanovich.[136] After years of being jabbed in the eyes, Abdul-Jabbar developed corneal erosion syndrome, occasionally experiencing pain when his eyes dry up. He missed three games in December 1986 due to the condition.[137]

Skyhook

Abdul-Jabbar was well known for his trademark "skyhook", a hook shot in which he bent his entire body (rather than just the arm) like a straw in one fluid motion to raise the ball and then release it at the highest point of his arm's arching motion. With his long arms and great height, the skyhook was difficult for a defender to block without committing a goaltending violation. As a right-handed player, he was stronger shooting the skyhook with his right hand than he was with his left, although he was adept at shooting it with either hand, making it a reliable and feared offensive weapon. According to Abdul-Jabbar, he learned the move in fifth grade after practicing with the Mikan Drill and soon learned to value it, as it was "the only shot I could use that didn't get smashed back in my face".[121]

Legacy

Abdul-Jabbar is the NBA's all-time leading scorer with 38,387 points, and he won a league-record six MVP awards.[1][138] He earned six championship rings, two Finals MVP awards, 15 NBA First or Second Teams, a record 19 NBA All-Star call-ups and averaging 24.6 points, 11.2 rebounds, 3.6 assists and 2.6 blocks per game.[22][139] He is ranked as the NBA's third leading all-time rebounder (17,440).[140] He is also the third all-time in registered blocks (3,189),[141] which is especially impressive because this stat was not recorded until the fourth year of his career (1974).[142]

Abdul-Jabbar combined dominance during his career peak with the longevity and sustained excellence of his later years.[138] He credited Bruce Lee with teaching him "the discipline and spirituality of martial arts, which was greatly responsible for me being able to play competitively in the NBA for 20 years with very few injuries."[143] After claiming his sixth and final MVP in 1980, Abdul-Jabbar continued to average above 20 points in the following six seasons,[1] including 23 points per game in his 17th season at age 38.[144] He made the NBA's 35th Anniversary Team, and was named one of its 50 greatest players of all time in 1996.[22] Abdul-Jabbar is regarded as one of the best centers ever,[8] and league experts and basketball legends frequently mentioned him when considering the greatest player of all time.[144] Former Lakers coach Pat Riley once said, "Why judge anymore? When a man has broken records, won championships, endured tremendous criticism and responsibility, why judge? Let's toast him as the greatest player ever."[1] Isiah Thomas remarked, "If they say the numbers don't lie, then Kareem is the greatest ever to play the game."[2] Julius Erving in 2013 said, "In terms of players all-time, Kareem is still the number one guy. He's the guy you gotta start your franchise with."[5] In 2015, ESPN named Abdul-Jabbar the best center in NBA history,[144] and ranked him No. 2 behind Michael Jordan among the greatest NBA players ever.[138] While Jordan's shots were enthralling and considered unfathomable, Abdul-Jabbar's skyhook appeared automatic, and he himself called the shot "unsexy".[1][138] Abdul-Jabbar's only recognized rookie card became the most expensive basketball card ever sold when it went for $501,900 at auction in 2016. That record has since been surpassed.[145]

NBA career statistics

| GP | Games played | GS | Games started | MPG | Minutes per game |

| FG% | Field goal percentage | 3P% | 3-point field goal percentage | FT% | Free throw percentage |

| RPG | Rebounds per game | APG | Assists per game | SPG | Steals per game |

| BPG | Blocks per game | PPG | Points per game | Bold | Career high |

| † | Won an NBA championship | * | Led the league | |

NBA record |

Regular season

| Year | Team | GP | GS | MPG | FG% | 3P% | FT% | RPG | APG | SPG | BPG | PPG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1969–70 | Milwaukee | 82* | — | 43.1 | .518 | — | .653 | 14.5 | 4.1 | — | — | 28.8 |

| 1970–71† | Milwaukee | 82 | — | 40.1 | .577 | — | .690 | 16.0 | 3.3 | — | — | 31.7* |

| 1971–72 | Milwaukee | 81 | — | 44.2 | .574 | — | .689 | 16.6 | 4.6 | — | — | 34.8* |

| 1972–73 | Milwaukee | 76 | — | 42.8 | .554 | — | .713 | 16.1 | 5.0 | — | — | 30.2 |

| 1973–74 | Milwaukee | 81 | — | 43.8 | .539 | — | .702 | 14.5 | 4.8 | 1.4 | 3.5 | 27.0 |

| 1974–75 | Milwaukee | 65 | — | 42.3 | .513 | — | .763 | 14.0 | 4.1 | 1.0 | 3.3* | 30.0 |

| 1975–76 | L.A. Lakers | 82 | — | 41.2 | .529 | — | .703 | 16.9* | 5.0 | 1.5 | 4.1* | 27.7 |

| 1976–77 | L.A. Lakers | 82 | — | 36.8 | .579* | — | .701 | 13.3 | 3.9 | 1.2 | 3.2 | 26.2 |

| 1977–78 | L.A. Lakers | 62 | — | 36.5 | .550 | — | .783 | 12.9 | 4.3 | 1.7 | 3.0 | 25.8 |

| 1978–79 | L.A. Lakers | 80 | — | 39.5 | .577 | — | .736 | 12.8 | 5.4 | 1.0 | 4.0* | 23.8 |

| 1979–80† | L.A. Lakers | 82 | — | 38.3 | .604 | .000 | .765 | 10.8 | 4.5 | 1.0 | 3.4* | 24.8 |

| 1980–81 | L.A. Lakers | 80 | — | 37.2 | .574 | .000 | .766 | 10.3 | 3.4 | .7 | 2.9 | 26.2 |

| 1981–82† | L.A. Lakers | 76 | 76 | 35.2 | .579 | .000 | .706 | 8.7 | 3.0 | .8 | 2.7 | 23.9 |

| 1982–83 | L.A. Lakers | 79 | 79 | 32.3 | .588 | .000 | .749 | 7.5 | 2.5 | .8 | 2.2 | 21.8 |

| 1983–84 | L.A. Lakers | 80 | 80 | 32.8 | .578 | .000 | .723 | 7.3 | 2.6 | .7 | 1.8 | 21.5 |

| 1984–85† | L.A. Lakers | 79 | 79 | 33.3 | .599 | .000 | .732 | 7.9 | 3.2 | .8 | 2.1 | 22.0 |

| 1985–86 | L.A. Lakers | 79 | 79 | 33.3 | .564 | .000 | .765 | 6.1 | 3.5 | .8 | 1.6 | 23.4 |

| 1986–87† | L.A. Lakers | 78 | 78 | 31.3 | .564 | .333 | .714 | 6.7 | 2.6 | .6 | 1.2 | 17.5 |

| 1987–88† | L.A. Lakers | 80 | 80 | 28.9 | .532 | .000 | .762 | 6.0 | 1.7 | .6 | 1.2 | 14.6 |

| 1988–89 | L.A. Lakers | 74 | 74 | 22.9 | .475 | .000 | .739 | 4.5 | 1.0 | .5 | 1.1 | 10.1 |

| Career | 1,560 | 625 | 36.8 | .559 | .056 | .721 | 11.2 | 3.6 | .9 | 2.6 | 24.6 | |

| All-Star | 18 |

13 | 24.9 | .493 | .000 | .820 | 8.3 | 2.8 | .4 | 2.1 |

13.9 | |

Source:[99]

Playoffs

| Year | Team | GP | GS | MPG | FG% | 3P% | FT% | RPG | APG | SPG | BPG | PPG |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1970 | Milwaukee | 10 | — | 43.5 | .567 | — | .733 | 16.8 | 4.1 | — | — | 35.2 |

| 1971† | Milwaukee | 14 | — | 41.2 | .515 | — | .673 | 17.0 | 2.5 | — | — | 26.6 |

| 1972 | Milwaukee | 11 | — | 46.4 | .437 | — | .704 | 18.2 | 5.1 | — | — | 28.7 |

| 1973 | Milwaukee | 6 | — | 46.0 | .428 | — | .543 | 16.2 | 2.8 | — | — | 22.8 |

| 1974 | Milwaukee | 16 | — | 47.4 | .557 | — | .736 | 15.8 | 4.9 | 1.3 | 2.4 | 32.2 |

| 1977 | L.A. Lakers | 11 | — | 42.5 | .607 | — | .725 | 17.7 | 4.1 | 1.7 | 3.5 | 34.6 |

| 1978 | L.A. Lakers | 3 | — | 44.7 | .521 | — | .556 | 13.7 | 3.7 | .7 | 4.0 | 27.0 |

| 1979 | L.A. Lakers | 8 | — | 45.9 | .579 | — | .839 | 12.6 | 4.8 | 1.0 | 4.1 | 28.5 |

| 1980† | L.A. Lakers | 15 | — | 41.2 | .572 | — | .790 | 12.1 | 3.1 | 1.1 | 3.9 | 31.9 |

| 1981 | L.A. Lakers | 3 | — | 44.7 | .462 | — | .714 | 16.7 | 4.0 | 1.0 | 2.7 | 26.7 |

| 1982† | L.A. Lakers | 14 | — | 35.2 | .520 | — | .632 | 8.5 | 3.6 | 1.0 | 3.2 | 20.4 |

| 1983 | L.A. Lakers | 15 | — | 39.2 | .568 | .000 | .755 | 7.7 | 2.8 | 1.1 | 3.7 | 27.1 |

| 1984 | L.A. Lakers | 21 | — | 36.5 | .555 | — | .750 | 8.2 | 3.8 | 1.1 | 2.1 | 23.9 |

| 1985† | L.A. Lakers | 19 | 19 | 32.1 | .560 | — | .777 | 8.1 | 4.0 | 1.2 | 1.9 | 21.9 |

| 1986 | L.A. Lakers | 14 | 14 | 34.9 | .557 | — | .787 | 5.9 | 3.5 | 1.1 | 1.7 | 25.9 |

| 1987† | L.A. Lakers | 18 | 18 | 31.1 | .530 | .000 | .795 | 6.8 | 2.0 | .4 | 1.9 | 19.2 |

| 1988† | L.A. Lakers | 24 | 24 | 29.9 | .464 | .000 | .789 | 5.5 | 1.5 | .6 | 1.5 | 14.1 |

| 1989 | L.A. Lakers | 15 | 15 | 23.4 | .463 | — | .721 | 3.9 | 1.3 | .3 | .7 | 11.1 |

| Career | 237 | 90 | 37.3 | .533 | .000 | .740 | 10.5 | 3.2 | 1.0 | 2.4 | 24.3 | |

Source:[99]

Athletic honors

- Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame (May 15, 1995)[146]

- College:

- 2× Associated Press College Basketball Player of the Year (1967, 1969)

- 2× Oscar Robertson Trophy winner (1967, 1968)

- 2× UPI College Basketball Player of the Year (1967, 1969)

- Three-time First Team All-American (1967–1969)

- Three-time NCAA champion (1967–1969)

- Most Outstanding Player in NCAA Tournament (1967–1969)

- Naismith College Player of the Year (1969)

- 3× First-team All-Pac-8 (1967–1969)

- National Collegiate Basketball Hall of Fame (2007)[147]

- National Basketball Association:

- Rookie of the Year (1970)

- Six-time NBA champion (1971, 1980, 1982, 1985, 1987, 1988)

- NBA MVP (1971, 1972, 1974, 1976, 1977, 1980)

- Sporting News NBA MVP (1971, 1972, 1974, 1976, 1977, 1980)

- Finals MVP (1971, 1985)

- Sports Illustrated magazine's "Sportsman of the Year" (1985)

- One of the 50 Greatest Players in NBA History (1996)

- First player in NBA history to play 20 seasons

- Ranked No.2 in ESPN's 100 greatest NBA players of all time #NBArank[148]

- November 16, 2012 – A statue of Abdul-Jabbar was unveiled in front of Staples Center on Chick Hearn Court, in Los Angeles.

Film and television

Playing in Los Angeles facilitated Abdul-Jabbar's trying his hand at acting. He made his film debut in Bruce Lee's 1972 film Game of Death, in which his character Hakim fights Billy Lo (played by Lee).

In 1980, he played co-pilot Roger Murdock in Airplane!.[22] Abdul-Jabbar has a scene in which a little boy looks at him and remarks that he is in fact Abdul-Jabbar,[149] spoofing the appearance of football star Elroy "Crazylegs" Hirsch as an airplane pilot in the 1957 drama that served as the inspiration for Airplane!, Zero Hour!.[150] Staying in character, Abdul-Jabbar states that he is merely Roger Murdock, an airline co-pilot, but the boy continues to insist that Abdul-Jabbar is "the greatest", but that, according to his father, he doesn't "work hard on defense" and that he does not "really try, except during the playoffs".[149] This causes Abdul-Jabbar's character to snap, "The hell I don't!", then grabs the boy and snarls that he has "been hearing that crap ever ever since I was at UCLA" and been "busting my buns every night!". He instructs the boy to "Tell your old man old man to drag [Bill] Walton and [Bob] Lanier up and down the court for 48 minutes".[149][151] When Murdock loses consciousness later in the film, he collapses at the controls wearing Abdul-Jabbar's goggles and yellow Lakers' shorts.[149] In 2014, Abdul-Jabbar and Airplane! co-star Robert Hays (character Ted Striker) reprised their Airplane! roles in a parody commercial promoting Wisconsin tourism.[152]

Abdul-Jabbar has had numerous other television and film appearances, often playing himself. He has had roles in movies such as Fletch, Troop Beverly Hills and Forget Paris, and television series such as Full House, Living Single, Amen, Everybody Loves Raymond, Martin, Diff'rent Strokes (his height humorously contrasted with that of diminutive child star Gary Coleman), The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air, Scrubs, 21 Jump Street,[153] Emergency!, Man from Atlantis, and New Girl.[154] Abdul-Jabbar played a genie in a lamp in a 1984 episode of Tales from the Darkside. He also played himself on the February 10, 1994, episode of the sketch comedy television series In Living Color.[155]

He also appeared in the television version of Stephen King's The Stand, played the Archangel of Basketball in Slam Dunk Ernest, and had a brief non-speaking cameo appearance in BASEketball.[156] Abdul-Jabbar was also the co-executive producer of the 1994 TV film The Vernon Johns Story.[157] He has also made appearances on The Colbert Report, in a 2006 skit called "HipHopKetball II: The ReJazzebration Remix '06"[158] and in 2008 as a stage manager who is sent out on a mission to find Nazi gold.[159] Abdul-Jabbar also voiced himself in a 2011 episode of The Simpsons titled "Love Is a Many Strangled Thing".[160] He had a recurring role as himself on the NBC series Guys with Kids, which aired from 2012 to 2013.[156] On Al Jazeera English he expressed his desire to be remembered not just as a player, but also as somebody who used their mind and made other contributions.[161]

In February 2019, he appeared in season 12 episode 16 of The Big Bang Theory, "The D&D Vortex".[162]

Abdul-Jabbar made a guest appearance as himself in a season 2 episode of Dave. The episode he appeared in was also named after him.[163]

Writing

In September 2018, Abdul-Jabbar was announced as one of the writers for the July 2019 revival of Veronica Mars.[164][165][166][167]

Documentaries

On February 10, 2011, Abdul-Jabbar debuted his film On the Shoulders of Giants, documenting the tumultuous journey of the famed yet often-overlooked Harlem Renaissance professional basketball team, at Science Park High School in Newark, New Jersey. The event was simulcast live throughout the school, city, and state.[168]

In 2015, he appeared in an HBO documentary on his life, Kareem: Minority of One.[169]

In 2020, Abdul-Jabbar was the executive producer and narrator of the History channel special Black Patriots: Heroes of the Revolution.[170] He was nominated for an Emmy Award for his narration.[171]

Reality television

Abdul-Jabbar participated in the 2013 ABC reality series Splash, a celebrity diving competition.[172]

In April 2018, Abdul-Jabbar competed in the all-athlete season of season 26 of Dancing with the Stars and partnered with professional dancer Lindsay Arnold.[173]

Writing and activism

Abdul-Jabbar became a best-selling author and cultural critic.[164][174] He published several books, mostly on African-American history.[139] His first book, his autobiography Giant Steps, was written in 1983 with co-author Peter Knobler. The book's title is an homage to jazz great John Coltrane, referring to his album Giant Steps. Others include On the Shoulders of Giants: My Journey Through the Harlem Renaissance, co-written with Raymond Obstfeld, and Brothers in Arms: The Epic Story of the 761st Tank Battalion, World War II's Forgotten Heroes, co-written with Anthony Walton, which is a history of an all-black armored unit that served with distinction in Europe.

Abdul-Jabbar has also been a regular contributor to discussions about issues of race and religion, among other topics, in national magazines and on television. He has written a regular column for Time, for example, and he appeared on Meet the Press on Sunday, January 25, 2015, to talk about a recent column, which pointed out that Islam should not be blamed for the actions of violent extremists, just as Christianity has not been blamed for the actions of violent extremists who profess Christianity.[175][176] When asked about being Muslim, he said: "I don't have any misgiving about my faith. I'm very concerned about the people who claim to be Muslims that are murdering people and creating all this mayhem in the world. That is not what Islam is about, and that should not be what people think of when they think about Muslims. But it's up to all of us to do something about all of it."[177]

In November 2014, Abdul-Jabbar published an essay in Jacobin magazine calling for just compensation for college athletes, writing, "in the name of fairness, we must bring an end to the indentured servitude of college athletes and start paying them what they are worth."[178]

Commenting on Donald Trump's 2017 travel ban, he strongly condemned it, saying, "The absence of reason and compassion is the very definition of pure evil because it is a rejection of our sacred values, distilled from millennia of struggle."[179]

Government appointments

Cultural ambassador

In January 2012, United States Secretary of State Hillary Clinton announced that Abdul-Jabbar had accepted a position as a cultural ambassador for the United States.[180] During the announcement press conference, Abdul-Jabbar commented on the historical legacy of African-Americans as representatives of U.S. culture: "I remember when Louis Armstrong first did it back for President Kennedy, one of my heroes. So it's nice to be following in his footsteps."[181] As part of this role, Abdul-Jabbar has traveled to Brazil to promote education for local youths.[182]

President's Council on Fitness, Sports, and Nutrition

Former President Barack Obama announced in his last days of office that he has appointed Abdul-Jabbar along with Gabrielle Douglas and Carli Lloyd to the President's Council on Fitness, Sports, and Nutrition.[183]

Citizens Coinage Advisory Committee

In January 2017, Abdul-Jabbar was appointed to the Citizens Coinage Advisory Committee by United States Secretary of the Treasury Steven Mnuchin. According to the United States Mint, Abdul-Jabbar is a keen coin collector whose interest in the life of Alexander Hamilton had led him into the hobby. He resigned in 2018 due to what the Mint described as "increasing personal obligations".[184]

Personal life

Abdul-Jabbar met Habiba Abdul-Jabbar (born Janice Brown) at a Lakers game during his senior year at UCLA.[185] They eventually married and together had three children: daughters Habiba and Sultana and son Kareem Jr., who played basketball at Western Kentucky after attending Valparaiso.[186][187] Abdul-Jabbar and Janice divorced in 1978. He has another son, Amir, with Cheryl Pistono. Another son, Adam, made an appearance on the TV sitcom Full House with him.[188]

Religion and name

At age 24 in 1971, he converted to Islam and became Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, which means "noble one, servant of the Almighty."[189] He was named by Hamaas Abdul Khaalis.[189] Abdul-Jabbar purchased and donated 7700 16th Street NW, a house in Washington, D.C., for Khaalis to use as the Hanafi Madh-Hab Center. Eventually, Kareem "found that [he] disagreed with some of Hamaas' teachings about the Quran, and [they] parted ways." He then studied the Quran on his own, and “emerged from this pilgrimage with my beliefs clarified and my faith renewed.”[189]

Abdul-Jabbar has spoken about the thinking that was behind his name change when he converted to Islam. He stated that he was "latching on to something that was part of my heritage, because many of the slaves who were brought here were Muslims. My family was brought to America by a French planter named Alcindor, who came here from Trinidad in the 18th century. My people were Yoruba, and their culture survived slavery... My father found out about that when I was a kid, and it gave me all I needed to know that, hey, I was somebody, even if nobody else knew about it. When I was a kid, no one would believe anything positive that you could say about black people. And that's a terrible burden on black people, because they don't have an accurate idea of their history, which has been either suppressed or distorted."[190]

In 1998, Abdul-Jabbar reached a settlement after he sued Miami Dolphins running back Karim Abdul-Jabbar[191] (now Abdul-Karim al-Jabbar, born Sharmon Shah) because he felt Karim was profiting off the name he made famous by having the Abdul-Jabbar moniker and number 33 on his Dolphins jersey. As a result, the younger Abdul-Jabbar had to change his jersey nameplate to simply "Abdul" while playing for the Dolphins. The football player had also been an athlete at UCLA.[192]

Health problems

Abdul-Jabbar suffers from migraines,[193] and his use of cannabis to reduce the symptoms has had legal ramifications.[194]

In November 2009, Abdul-Jabbar announced that he was suffering from a form of leukemia, Philadelphia chromosome-positive chronic myeloid leukemia, a cancer of the blood and bone marrow. The disease was diagnosed in December 2008, but Abdul-Jabbar said his condition could be managed by taking oral medication daily, seeing his specialist every other month and having his blood analyzed regularly. He expressed in a 2009 press conference that he did not believe that the illness would stop him from leading a normal life.[195][196] Abdul-Jabbar is now a spokesman for Novartis, the company that produces his cancer medication, Gleevec.[197]

In February 2011, Abdul-Jabbar announced via Twitter that his leukemia was gone and he was "100% cancer free".[198] A few days later, he clarified his misstatement. "You're never really cancer-free and I should have known that," Abdul-Jabbar said. "My cancer right now is at an absolute minimum."[197]

In April 2015, Abdul-Jabbar was admitted to hospital when he was diagnosed with cardiovascular disease. Later that week, on his 68th birthday, he underwent quadruple coronary bypass surgery at the UCLA Medical Center.[199]

Non-athletic honors

In 2016, Abdul-Jabbar was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by outgoing U.S. President Barack Obama.[200]

In 2011, Abdul-Jabbar was awarded the Double Helix Medal for his work in raising awareness for cancer research.[201][202] Also in 2011, Abdul-Jabbar received an honorary degree from New York Institute of Technology.[203]

In 2020, Abdul-Jabbar was nominated for the Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Narrator for his work on the documentary special Black Patriots: Heroes of The Revolution.[171]

Works

This list is incomplete; you can help by . (May 2016) |

Books

- Abdul-Jabbar, Kareem; Knobler, Peter (1983). Giant Steps. New York: Bantam Books.

- Kareem, with Mignon McCarthy (1990) ISBN 0-394-55927-4

- Selected from Giant Steps (Writers' Voices) (1999) ISBN 0-7857-9912-5

- Black Profiles in Courage: A Legacy of African-American Achievement, with Alan Steinberg (1996) ISBN 0-688-13097-6

- A Season on the Reservation: My Sojourn with the White Mountain Apaches, with Stephen Singular (2000) ISBN 0-688-17077-3

- Brothers in Arms: The Epic Story of the 761st Tank Battalion, World War II's Forgotten Heroes with Anthony Walton (2004) ISBN 978-0-7679-0913-6

- On the Shoulders of Giants: My Journey Through the Harlem Renaissance with Raymond Obstfeld (2007) ISBN 978-1-4165-3488-4

- What Color Is My World? The Lost History of African American Inventors with Raymond Obstfeld (2012) ISBN 978-0-7636-4564-9

- Streetball Crew Book One Sasquatch in the Paint with Raymond Obstfeld (2013) ISBN 978-1-4231-7870-5

- Streetball Crew Book Two Stealing the Game with Raymond Obstfeld (2015) ISBN 978-1423178712

- Mycroft Holmes with Anna Waterhouse (September 2015) ISBN 978-1-7832-9153-3

- Writings on the Wall: Searching for a New Equality Beyond Black and White with Raymond Obstfeld (2016) ISBN 978-1-6189-3171-9

- Coach Wooden and Me: Our 50-Year Friendship On and Off the Court (2017) ISBN 978-1538760468

- Becoming Kareem: Growing Up On and Off the Court (2017) ISBN 978-0316555388

- Mycroft Holmes and The Apocalypse Handbook. Illustrated by Josh Cassara. Titan Comics. 2017. ISBN 978-1785853005.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Mycroft and Sherlock with Anna Waterhouse (October 9, 2018) ISBN 978-1785659256

- Mycroft and Sherlock: The Empty Birdcage with Anna Waterhouse (September 24, 2019) ISBN 978-1785659300

Audio book

- On the Shoulders of Giants: An Audio Journey Through the Harlem Renaissance 8-CD Set Vol. 1–4, with Avery Brooks, Jesse L. Martin, Maya Angelou, Herbie Hancock, Billy Crystal, Charles Barkley, James Worthy, Julius Erving, Jerry West, Clyde Drexler, Bill Russell, Coach John Wooden, Stanley Crouch, Quincy Jones and other chart-topping musicians, as well as legendary actors and performers such as Samuel L. Jackson. (2008) ISBN 978-0-615-18301-5

References

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g "Kareem Abdul-Jabbar Bio". NBA.com. Archived from the original on January 19, 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Mitchell, Fred (March 23, 2012). "NBA's best all-time player? You be the judge". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved April 6, 2021.

- ^ "The Greatest Player in NBA History: Why Kareem Abdul-Jabbal Deserves the Title". bleacherreport.com. Retrieved June 3, 2013.

- ^ "The growing pains for seven-footer Kareem Abdul-Jabbar". The National. Retrieved June 3, 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Julius Erving interview, Grantland. Retrieved April 11, 2014.

- ^ chrissorr (August 17, 2014). "Wooden Part 4: Recruiting Lew Alcindor". Bruins Nation. Retrieved June 25, 2019.

- ^ "Kareem Abdul-Jabbar Biography and Interview". www.achievement.org. American Academy of Achievement.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "The Game's Greatest Giants Ever". espn.go.com. Retrieved July 25, 2013.

- ^ "25 Greatest Players in College Basketball". ESPN. Retrieved June 3, 2013.

- ^ "All-Time #NBArank 2". ESPN. Retrieved February 19, 2016.

- ^ "Kareem Abdul-Jabbar". imbd.com. Retrieved June 3, 2013.

- ^ "Books by Kareem Abdul-Jabbar". Amazon.com. Retrieved June 3, 2013.

- ^ "Kareem Abdul-Jabbar named U.S. global cultural ambassador". latimes.com. January 19, 2012. Retrieved June 3, 2013.

- ^ "President Obama Names Recipients of the Presidential Medal of Freedom". whitehouse.gov. November 16, 2016. Retrieved November 16, 2016 – via National Archives.

- ^ "Kareem Abdul-Jabbar Biography (1947-)".

- ^ "Kareem Abdul-Jabbar Biography and Interview". www.achievement.org. American Academy of Achievement.

- ^ New York Magazine."Childhood in New York". Accessed February 22, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f "Alcindor The Awesome". Ebony. Vol. 22 no. 5. March 1967. pp. 91–97. ISSN 0012-9011. Retrieved June 17, 2021.

- ^ "African American Registry: Mr. Basketball and much more, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar!". The African American Registry. Archived from the original on October 27, 2006.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Kareem Abdul-Jabbar biography". biography channel online. A&E. 2013.

- ^ The New Encyclopedia Britannica (Fifteenth ed.). 2007. p. 20. ISBN 9781593392925. Retrieved May 19, 2020 – via Archive.org.

Alcindor played for Power Memorial Academy (at 6 feet 8 inches) on the varsity for four years, and his total of 2,067 points set a New York City high school record.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i Dawson, Dawn P, ed. (2010) [1992]. Great athletes: Basketball (Revised ed.). Salem Press. pp. 1–4. ISBN 9781587654732. Retrieved June 6, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Didinger, Ray, "They Still Remember Power's Tower", philly.com, May 25, 1989.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f "Kareem Abdul-Jabbar". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved May 19, 2020.

- ^ Olympic Talk (May 22, 2017), "Kareem Abdul-Jabbar details passing on 1968 Olympics in new book", NBC Sports.

- ^ McSweeney, John (February 25, 1966). "Rival cage coaches agree Alcindor may be greatest". Spokesman-Review. (Spokane, Washington). Associated Press. p. 20.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Lopresti, Mike (March 3, 2017). "Remembering the start of UCLA's dynasty, 50 years later". NCAA.com. Retrieved June 18, 2021.

- ^ Smith, Dean (October 2, 1983). "Why Freshman Should Not Play". The New York Times. Retrieved June 18, 2021.

- ^ "21 Turn Out As UCLA Opens Cage Practice". The San Francisco Examiner. UPI. October 16, 1965. p. 28. Retrieved June 18, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Florence, Mal (November 28, 1965). "Who's No. 1? UCLA Frosh Too Hot for Varsity, 75–60". Los Angeles Times. Sec. D, pp. 1, 10. Retrieved June 14, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

Lew Alcindor strode onto the Pauley Pavilion court Saturday night and captured the town, completely demoralizing the UCLA varsity basketball team in the process

- ^ "Basketball Teams to Dedicate Pavilion". Los Angeles Times. November 21, 1965. p. K-5. Retrieved June 18, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Crowe, Jerry (May 27, 1990). "A Grand Opening : Pauley Pavilion and UCLA's Best Freshman Team Made Their Debuts Together 25 Years Ago". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved June 18, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Bruins Are Beaten—By Freshman Quintet". Corvallis Gazete-Times. November 29, 1965. p. 10. Retrieved June 18, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Wittry, Andy (August 12, 2020). "Kareem Abdul-Jabbar: College stats, best moments, quotes". NCAA.com. Retrieved June 18, 2021.

- ^ "sports illustrated 1967 cover; basketballs new superstar: lew alcindor - Google Search". www.google.com. Retrieved June 25, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Lew's Still Loose". Time Magazine. April 14, 1967. Retrieved June 27, 2020.

- ^ McLeaod, Mac (April 8, 1976). "The Dunk Is Back, What Does It Bring". The Daily Item. p. 1B. Retrieved June 18, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Bill Littlefield (May 19, 2017). "50 Years Of Coach Wooden And Kareem, Through Racism, Olympic Boycotts And More". WBUR-FM. Retrieved April 15, 2020.

- ^ Crowe, Jerry (February 2, 2009). "His USC team stood around and waited to beat UCLA". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved June 18, 2021.

- ^ Johnson, Gary K. (2005). "NCAA Men's Basketball Finest" (PDF). National Collegiate Athletic Association. p. 11. ISSN 1521-2955. Retrieved December 25, 2018.

- ^ "Men's Basketball Award Winners" (PDF). NCAA.com. p. 16. Retrieved June 18, 2021.

- ^ "Lew Alcindor HeadsHelms All American Hoop Quintet". The Daily Herald. p. 8. Retrieved June 18, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Florence, Mal (April 7, 1974). "Papa Sam Gilbert is someone special to UCLA cagers". Sarasota Herald-Tribune. (Florida). (Los Angeles Times). p. 7D.

- ^ Prugh, Jeff (January 14, 1968). "Bruins win again without Alcindor. Big Lew Sidelined By Eye Injury Suffered in Game against Bears". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Nguyen, Thuc Nhi (January 19, 2018). "UCLA-Houston 'Game of the Century' still leaves impression 50 years later". Los Angeles Daily News. Archived from the original on January 27, 2020.

Eight days after scratching his cornea against Cal, Abdul-Jabbar was one of four UCLA starters to play all 40 minutes.

- ^ "Los Angeles Lakers center Kareem Abdul-Jabbar flew home from Dallas". United Press International. December 20, 1986. Archived from the original on January 27, 2020.

Jabbar, who wears goggles to protect his eyes during play, is suffering from recurring corneal erosion syndrome in his right eye. He returned to Los Angeles following an eye examination in Dallas early Saturday. Doctors explained that because Jabbar was poked in the eye so many times in the days before he wore goggles, scar tissue had formed on the cornea.

- ^ "Lakers Now". Los Angeles Times. January 27, 2006. Archived from the original on February 2, 2006. Retrieved August 10, 2006.

- ^ Huang, Mike (November 30, 2017). "How Bruce Lee became a muse for Kareem and an All-Rookie guard". ESPN.com. Retrieved June 17, 2021.

- ^ Wizig, Jerry (January 20, 1988). "It's been 20 years since they've played The Game of the Century". Houston Chronicle. Archived from the original on October 4, 2021.

- ^ Esper, Dwain (March 25, 1968). "Bruins Hope Norman Stays". The Independent. Pasadena, California. p. 15. Retrieved July 22, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Gasaway, John (June 7, 2010). "John Wooden's Century". Basketball Prospectus. Archived from the original on July 23, 2015. Retrieved July 23, 2015.

- ^ "Lew's Revenge: The Rout of Houston". Archived from the original on May 6, 2019. Retrieved March 7, 2019.

- ^ Diamant, Jeff (2010). "Abdul-Jabbar, Kareem (Lew Alcindor)". In Curtis, Edward E., IV (ed.). Encyclopedia of Muslim-American History (1st ed.). New York: Facts On File. pp. 2–3. ISBN 978-1-4381-3040-8. OCLC 650849872. Retrieved January 15, 2020 – via Google Books.

- ^ Black Journal; 60; Kareem, archived from the original on February 24, 2021, retrieved June 15, 2020

- ^ UCLA 2019-2020 Men's basketball Information Guide (uclabruins.com) The 2019-20 UCLA men’s basketball information guide is a copyright production of the UCLA Athletic Communications Office, J.D. Morgan Center, 325 Westwood Plaza, Los Angeles, Calif., 90095

- ^ 2009–10 UCLA men's basketball media guide Archived July 17, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved October 26, 2009.

- ^ "New York Nets (1968 - 1975) 1969 Stats, History, Awards and More". Archived from the original on May 18, 2015.

- ^ Scorecard. Sports Illustrated, April 7, 1969

- ^ "Alcindor Rejects A.B.A.'s $3.2-Million Offer and Will Sign With Bucks". The New York Times. March 30, 1969.

- ^ "Seattle SuperSonics vs Milwaukee Bucks Box Score, February 21, 1970". Basketball-Reference. Retrieved March 24, 2020.

- ^ "Philadelphia 76ers at Milwaukee Bucks Box Score, April 3, 1970". Basketball-Reference. Retrieved March 24, 2020.

- ^ "Jayson Tatum's rookie season ranks alongside best in Celtics' history". Sporting News. June 18, 2018. Retrieved June 6, 2021.

- ^ "... And Bucks Win Sixth". The Ithaca Journal. December 15, 1971. p. 26. Retrieved June 6, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Oscar Had No Doubt". Wisconsin State Journal. May 1, 2021. Section 3, page 1. Retrieved July 13, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Spears, Marc J. (July 12, 2021). "Giannis dominating like Kareem revives Bucks' title hopes". The Undefeated. Retrieved July 13, 2021.

- ^ Smith, Terence (June 4, 1971). "Biggest Name in N.B.A.: Jabbar". The New York Times. p. 27. Retrieved June 6, 2021.

- ^ Seppy, Tom (June 4, 1971). "Kareem Abdul Jabbar (Also Known As Lew Alcindor) To Tour Africa". Sheboygan Press. Associated Press. p. 21. Retrieved June 6, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Abdul-Jabbar is Most Valuable". Kenosha News. UPI. March 22, 1971. p. 25. Retrieved June 6, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Basketball Pro Chart". The Lompoc Record. Newspaper Enterprise Association. October 24, 1974. p. 7. Retrieved June 6, 2021 – via Newspaper.com.

- ^ "Jabbar—Most Valuable Player". The Fresno Bee. AP. March 21, 1974. p. D1. Retrieved June 6, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Putnam, Pat (December 9, 1974). "Return of Ol Goggle-Eyes". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved June 7, 2021.

- ^ Goldaper, Sam (September 4, 1974). "Robertson Ends Career". The New York Times. p. 33. Retrieved June 7, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Bonk, Thomas (December 25, 1987). "June 16, 1975: A Banner Day For Lakers : Kareem Takes His Post : 4 Players Bucks Got in Trade Gone, but He's Still on Job". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved June 6, 2021.

- ^ Goldaper, Sam (March 18, 1975). "Bucks See No Need Now to Make Deal for Unhappy Abdul‐Jabbar". The New York Times.

- ^ "Say It Ain't So Milwaukee Bucks". SI.com. May 30, 2001. Archived from the original on November 4, 2012. Retrieved June 10, 2007.

- ^ "Abdul‐Jabbar Fractures Hand". The New York Times. AP. October 6, 1974. Section 5, page 1. Retrieved June 6, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Kareem Looks Different, Acts The Same". Wisconsin State Journal. November 25, 1974. Section 2, page 1. Retrieved June 6, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Jabbar on the move?". The Journal-News. March 14, 1975. p. 14B. Retrieved June 7, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Jabbar Finally Confirms It: He Wants To Be Traded". Los Angeles Times. UPI. March 15, 1975. Part III, p. 1. Retrieved June 7, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Cady, Steve (June 17, 1975). "Abdul‐Jabbar Traded by Bucks for Four Lakers". The New York Times. Retrieved June 7, 2021.

- ^ "Third NBA Scoring Title For McAdoo". The Sacramento Bee. April 13, 1976. p. C4. Retrieved June 7, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Kareem keeps getting better". The Bakersfield Californian. October 7, 1976. p. 27. Retrieved June 7, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Bock, Hal. "Special K : Kareem Abdul-Jabbar Survived on Talent and a Quiet Dignity". Los Angeles Times. Associated Press. Retrieved June 7, 2021.

- ^ "The Players' Player: Jabbar". Los Angeles Times. April 2, 1976. Section III, p. 2. Retrieved June 7, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Abadie, Chuck (April 13, 1976). "Jabbar is most valuble player?". Hattiesburg American. p. 14. Retrieved June 7, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Goldaper, Sam (May 24, 1977). "Abdul‐Jabbar Is Chosen M.V. P. for a Fifth Time". The New York Times. Retrieved June 7, 2021.

- ^ Dwyer, Kelly (September 4, 2014). "Dunk History: A healthy Bill Walton meets Kareem Abdul-Jabbar at the summit". Ball Dont Lie. Retrieved June 7, 2021.

- ^ Kirkpatrick, Curry (May 23, 1977). "L.A. COULDN'T MOVE THE MOUNTAIN". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved June 7, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Green, Ted (October 19, 1977). "Jabbar scores KO Over Benson". Los Angeles Times. Sec. III, pp. 1, 10. Retrieved June 12, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Montgomery, Paul L. (October 21, 1977). "Abdul‐Jabbar Fined $5,000 for One Punch". The New York Times. Retrieved June 12, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Wolfley, Pete (February 20, 2011). "Benson's NBA start did not lack punch". Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel. Retrieved June 12, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Simmons, Bill (2009). The Book of Basketball: The NBA According to the Sports Guy. New York City: ESPN Books. p. 133. ISBN 978-0-345-51176-8.

- ^ Bonk, Thomas (May 16, 1985). "Abdul-Jabbar Tells His Side of the Fight--Just to League Office". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved June 12, 2021.

- ^ Green, Ted (December 4, 1977). "An Added Punch*". Los Angeles Times. Part III, p. 1. Retrieved June 12, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Jabbar replaces Magic for 19th All-Star game". Journal Gazette. Mattoon, Illinois. AP. February 11, 1989. p. B-3. Retrieved June 12, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "After Another Hearing, Kuhn Still Undecided on Blue Deal". Los Angeles Times. January 25, 1978. Part III, p. 4. Retrieved June 12, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Green, Ted (January 25, 1978). "Jabbar Silences Critics, 76ers—and Jabbar". Los Angeles Times. Part III, pp. 1–6. Retrieved June 12, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Green, Ted (February 4, 1978). "Lakers Pull One Out of the Fire". Los Angeles Times. Part III, p. 1–5. Retrieved June 12, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Kareem Abdul-Jabbar Stats". Basketball-Reference.com. Retrieved June 13, 2021.

- ^ Green, Ted (April 26, 1979). "SuperSonics Finish Off The Lakers, 106–101". Los Angeles Times. Part III, p. 1. Retrieved June 13, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Pearlman, Jeff (May 14, 2014). "The 'Magic' coin flip (book excerpt)". ESPN.com. Retrieved June 13, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Knoblauch, Austin (October 11, 2011). "Kareem Abdul-Jabbar". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved June 13, 2021.

- ^ Schwartz, Larry. "Kareem just kept on winning". ESPN.com. Retrieved June 13, 2021.

- ^ "Kareem Abdul-Jabbar is hot for yoga". Archived from the original on December 6, 2003. Retrieved May 23, 2006.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- ^ sports and yoga Posted by: dionne on 10-Jan-11 (January 13, 2011). "Kareem Abdul-Jabbar does Bikram Yoga". Bikramyogavernon.com. Archived from the original on March 21, 2012. Retrieved August 10, 2012.

- ^ Thomas, Ron (February 11, 1983). "NBA Notes: Kareem loses a lot". USA Today. p. 5C.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Talking with Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Part I". Los Angeles Times. January 25, 2006. Archived from the original on September 15, 2018. Retrieved May 2, 2010.

- ^ Littwin, Mike (June 18, 1989). "Pistons Win Title With Huge Asterisk Attached". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved June 14, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Baker, Chris (June 22, 1988). "Abdul-Jabbar Makes a Promise—He'll Return". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved June 15, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Abdul-Jabbar will return for one final season with Lakers". News Journal. Mansfield, Ohio. June 23, 1988. pp. 1-B, 5-B. Retrieved June 15, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "The Lakers:Player by Player: Kareem Abdul-Jabbar". Los Angeles Times. June 23, 1988. Part III-A, p. 9. Retrieved June 15, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Goldstein, Alan (June 23, 1988). "Guarantees no longer necessary". Shreveport Journal. p. 3C. Retrieved June 15, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Frauenheim, Norm (June 22, 1988). "Riley's prophecy now lore". The Arizona Republic. pp. F1, F3. Retrieved June 15, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Jump up to: a b McManis, Sam (April 23, 1989). "A Last Hurrah: For Abdul-Jabbar, a Season of Farewells Will Be Capped Today". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved June 14, 2021.

- ^ Johnson, Earvin "Magic"; Novak, William (1992). My Life. Random House. p. 124. ISBN 9780679415695. Retrieved June 15, 2021 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "10 memories top his all-time list of great moments". Des Moines Sunday Register. April 30, 1989. p. 13D. Retrieved June 14, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Broussard, Chris (April 25, 2004). "A Legend Learns That He Needs to Be Liked". The New York Times. Retrieved June 16, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Plaschke, Bill (December 2, 1997). "Abdul-Jabbar Figures NBA Needs a Coach Kareem". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved June 16, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Johnson, Earvin "Magic"; Novak, William (1992). My Life. Random House. pp. 121–123. ISBN 9780679415695. Retrieved June 15, 2021 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Rogers, John (February 16, 2018). "A talkative Kareem Abdul-Jabbar reflects on becoming himself". Associated Press. Retrieved June 16, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Talking with Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Part II". Los Angeles Times. January 27, 2006. Archived from the original on September 15, 2018. Retrieved May 2, 2010.

- ^ Beard, Alison (January–February 2012). "Life's Work: An Interview with Kareem Abdul-Jabbar". Harvard Business Review. Retrieved June 16, 2021.

- ^ Crowe, Jerry (September 7, 2005). "Kareem Hopes to Teach Young Laker a Lesson". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 16, 2020.

- ^ Jonathan Lemire (January 2004). "Keeping Up". Columbia College Today. Archived from the original on June 10, 2007. Retrieved June 10, 2007.

- ^ Doug Cantor (June 1, 2004). "Esquire: Q + A: Kareem Abdul-Jabbar". Retrieved June 10, 2007.

- ^ "LAKERS: Lakers hire Kareem Abdul-Jabbar as Special Assistant Coach". NBA.com. September 2, 2005. Retrieved June 10, 2007.

- ^ Markazi, Arash (May 19, 2011). "Kareem Abdul-Jabbar unhappy". ESPN.com. Retrieved April 16, 2020.

- ^ "Kareem Abdul-Jabbar Volunteers As High School Coach On Indian Reservation in Arizona". Jet. November 23, 1998. Archived from the original on October 12, 2007. Retrieved June 10, 2007.

- ^ Abramson, Mitch. "Kareem Abdul-Jabbar promotes new book, says he is not upset about lack of coaching opportunity in NBA". New York Daily News. Retrieved June 16, 2021.

- ^ Williams, Janice (July 12, 2016). "2016 Espy Award Nominees". Archived from the original on July 15, 2016. Retrieved July 15, 2016.

- ^ "Kareem calls out Howard for play". ESPN. June 12, 2009. Retrieved August 11, 2017.

- ^ "NBA & ABA Career Leaders and Records for Field Goal Pct - Basketball-Reference.com".

- ^ Hartman, Steve; Smith, Matt (2009). The Great Book of Los Angeles Sports Lists. Basic Civitas Books. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-7624-3520-3.

- ^ Johnson, Roy S. (May 22, 1983). "The Long-Run Success Of Kareem Abdul-Jabbar". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 7, 2016.

- ^ "NBA & ABA Career Leaders and Records for Games". Basketball Reference. April 27, 2020. Retrieved June 30, 2020.

Robert Parish - 1611.

- ^ "Addul-Jabbar to miss two games". The Morning News. Associated Press. October 14, 1980. p. B2 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Abdul-Jabbar out with eye trouble". The Spokesman-Review. December 21, 1986. p. D2 – via Newspaper.com.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "All-Time #NBArank: Kareem No. 2". ESPN.com. February 10, 2016. Archived from the original on February 11, 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Rhoden, William C. (June 14, 2017). "Locker Room Talk: Abdul-Jabbar Is The Best Basketball Player—Period". The Undefeated. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ^ "NBA History – Rebounds Leaders". espn.go.com. Retrieved June 29, 2012.

- ^ "All Time Leaders: Blocks". nba.com. Archived from the original on June 20, 2013. Retrieved June 3, 2013.

- ^ Pro Basketball's All-Time All-Stars: Across the Eras. p. xxxi. Scarecrow Press, 2013.

- ^ Kareem Abdul-Jabbar: Bruce Lee Was My Friend, and Tarantino's Movie Disrespects Him. The Hollywood Reporter. August 16, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "All-time #NBArank: Counting down the 10 greatest centers ever". ESPN.com. January 19, 2016. Archived from the original on January 20, 2016.

- ^ "Heritage Auctions Summer Platinum Night Auction commands $13.67+ Million". sports.ha.com. Heritage Auctions. August 30, 2016. Retrieved August 28, 2020.

- ^ "Hall of Famers". Basketball Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on April 20, 2010. Retrieved August 2, 2009.

- ^ JOHN MARSHALL: Abdul-Jabbar Honored by College Hall Associated Press. November 18, 2007.

- ^ "The ESPN all-time #NBArank". ESPN. Archived from the original on February 13, 2016. Retrieved February 10, 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Zupanic, Jeffrey (April 5, 2017). "Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, from 'Airplane!' to Mount Union". Kent Record-Courier. Retrieved July 12, 2021.

- ^ Mertes, Micah (May 24, 2017). "'Don't call me Shirley': Memorable 'Airplane' lines, little-known facts". Omaha World-Herald. Retrieved July 12, 2021.

- ^ Abrahams, Jim; Zucker, David; Zucker, Jerry (June 11, 1979). "A I R P L A N E ! Shooting Script". Retrieved July 13, 2021 – via DailyScript.com.

- ^ Nicks, Denver (March 4, 2014). "Kareem Abdul-Jabbar Reprises 'Airplane' Role in Wisconsin Tourism Ad". Time. Retrieved July 12, 2021.

- ^ "Kareem Abdul-Jabaar". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ^ Mark Medina (April 10, 2012). "Kareem Abdul-Jabbar guest stars on Fox's 'New Girl' on Tuesday". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 12, 2012.

- ^ Fields, Curt (April 14, 2006). "An All-Star Lineup 'In Living Color'". The Washington Post. Retrieved July 13, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Kareem Abdul-Jabbar List of Movies and TV Shows". TVGuide.com. Retrieved July 13, 2021.

- ^ Kilian, Michael. "Vernon Johns: A New Hero For America". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved July 13, 2021.

- ^ 2006 The Colbert Report appearance

- ^ 2008 The Colbert Report appearance

- ^ "The Simpsons - Season 22 Episode 17". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved July 13, 2021.

- ^ One on One - Kareem Abdul Jabbar - Part 2. Al Jazeera English. February 6, 2010. Event occurs at 10:10. Retrieved July 13, 2021.

- ^ Dicker, Ron (February 6, 2019). "Melissa Rauch And Kareem Abdul-Jabbar Make Quite A Pair In 'Big Bang Theory' Photo". HuffPost. Retrieved February 24, 2019.

- ^ "How Kareem Abdul-Jabbar dunking on 'Dave' fits rapper's self-deprecating TV persona". USAToday.com.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Desta, Yohana (September 26, 2018). "Yes, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar Is Really Writing for the New Veronica Mars". HWD. Retrieved June 9, 2019.

- ^ Gelman, Vlada (April 28, 2019). "How Kareem Abdul-Jabbar Ended Up Writing for the Veronica Mars Revival". TVLine. Retrieved June 9, 2019.

- ^ Polacek, Scott (September 25, 2018). "Kareem Abdul-Jabbar Joins Writing Staff of 'Veronica Mars' TV Show Reboot". Bleacher Report. Retrieved June 9, 2019.

- ^ "Veronica Mars Writers Room Adds Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Of Course". www.vulture.com. September 25, 2018. Retrieved June 9, 2019.

- ^ "Kareem Abdul-Jabbar tells Newark students a tale worth learning". New Jersey Star Ledger. February 11, 2011. Retrieved February 11, 2011.

- ^ Lowry, Brian (November 2, 2015). "TV Review: 'Kareem: Minority Of One'". Variety. Archived from the original on November 4, 2015.

- ^ "HISTORY® Announces 'Black Patriots: Heroes of the Revolution'". History.com. Retrieved July 13, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Kareem Abdul-Jabbar". Emmys.com. Retrieved July 13, 2021.

- ^ "Bucks Legend Kareem Abdul Jabbar Making a Splash" (Press release). NBA.com. February 8, 2013.

- ^ Thorbecke, Catherine (April 13, 2018). "Adam Rippon, Tonya Harding and more superstar athletes to face-off in Dancing With the Stars season 26". ABC News. Retrieved April 13, 2018.

- ^ Carroll, Rory (April 15, 2020). "On this day: Born April 16, 1947: Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, American basketball player". Reuters. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ^ "These Terrorist Attacks Are Not About Religion". Time. Retrieved January 27, 2015.

- ^ "Kareem Abdul-Jabbar on Meet the Press". nbc.com. Retrieved January 27, 2015.

- ^ "Kareem Abdul-Jabbar: 'If It's Time To Speak Up, You Have To Speak Up'", NPR interview with Michel Martin, November 1, 2015.

- ^ Abdul-Jabbar, Kareem (November 12, 2014). "College Athletes of the World, Unite". Jacobin. Retrieved December 14, 2014.

- ^ Long, Michael G. (February 9, 2021). 42 Today: Jackie Robinson and His Legacy. ISBN 9781479805624.

- ^ Beck, Howard (January 18, 2012). "Abdul-Jabbar Drafted by U.S. as Cultural Ambassador". The New York Times. Retrieved August 20, 2019.

- ^ Remarks With Cultural Ambassador Kareem Abdul-Jabbar . U.S. Department of State. January 18, 2012.

- ^ "Kareem Abdul-Jabbar - Global Cultural Ambassador - Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs". eca.state.gov.

- ^ "Obama makes wave of final appointments for well-connected friends, celebs". Fox News. January 18, 2017. Retrieved January 18, 2017.

- ^ "Kareem Abdul-Jabbar to Step Down from Citizens Coinage Advisory Committee". usmint.gov. United States Mint. Retrieved April 21, 2019.

- ^ Abdul-Jabbar, Kareem (1983). Giant Steps. New York: Bantam Books. p. 227. ISBN 0-553-05044-3.

- ^ "Kareem's Son To Leave Valparaiso". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved February 21, 2019.

- ^ "The Official Website of Kareem Abdul-Jabbar " 2008 " March". Kareemabduljabbar.com. Archived from the original on November 23, 2012. Retrieved December 18, 2012.

- ^ Toone, Stephanie (June 13, 2020). "Kareem Abdul-Jabbar's son accused of stabbing his neighbor". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Abdul-Jabbar, Kareen (March 29, 2015). "Why I converted to Islam". Opinion. Al Jazeera. Retrieved January 26, 2020.

- ^ Sportsline[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Abdul-Jabbars Settle Their Suit". The New York Times. Associated Press. April 30, 1998. Retrieved August 20, 2019.

- ^ "NBA great Kareem Abdul-Jabbar wants NFL player to stop using name - the former Sharmon Shah, Miami Dolphin running back being sued by former basketball player". Jet. December 1, 1997. Archived from the original on March 12, 2007. Retrieved August 16, 2005.

- ^ Anderson, Dave (May 28, 1984). "Transferring A Headache". The New York Times. Retrieved May 2, 2010.

- ^ "Abdul-Jabbar in drug arrest". BBC Sport. July 19, 2000. Retrieved May 2, 2010.