Karl Wilhelm von Stutterheim

Karl Wilhelm von Stutterheim | |

|---|---|

| Born | 6 August 1770 Berlin, Kingdom of Prussia |

| Died | 13 December 1811 (aged 41) Vienna, Austrian Empire |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | Cavalry, Staff |

| Years of service | Austria: 1799-1811 |

| Rank | Lieutenant General |

| Battles/wars | French Revolutionary Wars Napoleonic Wars |

| Awards | Pour le Mérite, 1793 Military Order of Maria Theresa, KC 1809 |

Karl Daniel Gottfried Wilhelm von Stutterheim, born 6 August 1770 – died 13 December 1811, served in the Prussian and Saxon armies during the French Revolutionary Wars, leaving the latter service in 1798. He spent most of his career in the army of Habsburg Austria and the Austrian Empire. He commanded a brigade in combat against the First French Empire during the 1805 and 1809 wars. In the latter conflict, he led his troops with dash and competence. He authored two histories about the wars; the second work remained unfinished due to his suicide in 1811.

Early career[]

Stutterheim was born in Berlin in the Kingdom of Prussia on 6 August 1770. He was elevated to the noble rank of Freiherr on 20 November 1784. He earned the Prussian Pour le Mérite order on 2 October 1793.[1] This occurred shortly after the Battle of Pirmasens on 14 September, though there is no evidence that he fought in that action.[2] The year 1798 found him in the army of the Electorate of Saxony with the rank of major. He resigned on 28 March 1798 and took service with Austria on 10 January 1799. The Austrians appointed him a major on 18 November 1799.[1]

Austrian service: 1799-1805[]

On 4 April 1800, Michael von Melas led the 62,000-strong Austrian army in operations against the French-held city of Genoa.[3] Despite savage fighting, especially on 7 April, the Austrians invested the city and began the Siege of Genoa.[4] At dawn on 30 April, the Austrian Kray and Alvinczi Infantry Regiments seized the Deux-Frères (Two Brothers) redoubt atop Monte Fratelli. André Masséna sent a column of grenadiers to retake the fort and the French ejected the Austrians from the fortification.[5] Now a staff officer, Stutterheim was on the scene and sent an urgent message requesting reinforcements, though he neglected to mention how many were needed. With typical Austrian rigidity, the local general refused to honor the request until his superior, Ludwig von Vogelsang approved it. By the time Vogelsang acted on the information, the fort was firmly back in French hands.[6] He received promotion to Oberstleutnant in 1801 and Oberst (colonel) in 1803.[1]

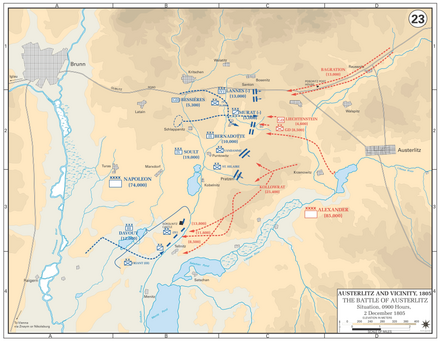

Stutterheim was promoted to General-Major on 24 October 1805 during the War of the Third Coalition.[1] At the Battle of Austerlitz on 2 December 1805, he led a cavalry brigade in Michael von Kienmayer's Advance Guard column. His command included eight squadrons of the O'Reilly Chevau-léger Regiment Nr. 3, about 900 sabers, and 40 troopers of the Merveldt Uhlan Regiment Nr. 1.[7][8] Kienmayer's force was assigned to clear the village of Telnice (Tellnitz) of the French. Before 8:00 AM, the Austrians bumped into several companies of French infantry deployed outside of Telnice.[9] Kienmayer ordered one battalion of the 1st Szekler Grenz Infantry Regiment Nr. 14 to attack a vineyard-covered hill on which the French were posted. The first battalion soon lost half its strength, forcing the commitment of the second battalion to the fight. Johann Nepomuk von Nostiz-Rieneck guarded the right flank with the Hessen-Homburg Hussar Regiment Nr. 4, while Moritz Liechtenstein protected the left flank with the Szekler Hussar Regiment Nr. 11. French marksmen picked off a number of the hussars who hovered too close.[10]

Kienmayer put Stutterheim in charge of the two Szekler grenzer battalions, who finally captured the knoll after being thrown back twice. The French covering force fell back to Telnice and nearby vineyards, which were vigorously defended by the 3rd Line Infantry Regiment. Even after Kienmayer sent in Georg Symon de Carneville's three Grenz infantry battalions, the Austrians were unable to seize the village. At one point, the French nearly recaptured the hill on which Stutterheim's two battalions stood.[11] After an hour, Friedrich Wilhelm von Buxhoeveden marched up with the Russians of the 1st Column. Carneville's grenzers, backed by the Russian 7th Jäger Regiment, stormed Telnice and drove the French beyond the stream on the west side of the village. At this moment, 4,000 French reinforcements appeared and recaptured the village under cover of a fog that rolled in. Nostiz led an effective charge with his hussars which captured many of their enemies and soon the French were driven out of Telnice again.[12]

This triumph allowed Liechtenstein and Stutterheim to deploy their cavalry brigades on the west side of the stream. But because the 2nd Column had not kept contact with the 1st Column and Advance Guard, the allied generals halted the troops.[13] When their leaders finally became aware of the French breakthrough of the center, the 1st Column attempted to go to the rescue, but marched in the wrong direction. The Austrian cavalry was pulled back, abandoning Telnice, and a few battalions were deployed nearby to cover Buxhoeveden's retreat. Liechtenstein with the Szekler Hussars and Stutterheim with the O'Reilly Chevau-légers plus two regiments of Cossacks covered the rear of the withdrawing 1st Column.[14]

Dominique Vandamme's victorious division took the 1st Column in flank at the village of Újezd u Brna (Aujest). Buxhoeveden got away with the lead elements, but 4,000 Allies became prisoners and Dmitry Dokhturov's troops were cut off with their backs to some lakes near the southern edge of the battlefield. By this time a number of French artillery batteries unlimbered within range. Dokhturov's troops passed near Telnice again before escaping across a narrow dike between two lakes. Liechtenstein and Stutterheim's cavalry covered the retreat, though they suffered heavy losses from grape-shot fired the nearby enemy batteries. Most of the Russian cannons were abandoned during the retreat, though Stutterheim managed to save the guns assigned to the O'Reilly Hussars.[15]

Stutterheim wrote La Bataille d'Austerlitz in July 1806, which was published in English as A Detailed Account of the Battle of Austerlitz in 1807.[16]

Austrian service: 1809[]

At the beginning of the War of the Fifth Coalition, Stutterheim was appointed to lead a brigade in Hannibal Sommariva's Light Division belonging to Prince Franz Seraph of Rosenberg-Orsini's IV Armeekorps. The brigade consisted of two battalions of the Deutsch-Banater Grenz Infantry Regiment Nr. 12, eight squadrons of the Vincent Chevau-léger Regiment Nr. 4, and a 3-pound Grenz brigade battery with eight pieces.[17] On 19 April 1809, the main armies met at the Battle of Teugen-Hausen in Bavaria. Leading the IV Armeekorps advance guard, Stutterheim located Claude Petit's French infantry brigade in the woods at Schneidert to the east of Hausen. He attacked but was repulsed after a prolonged action. Rosenberg led the bulk of his troops farther east to Dünzling where they finally drove back a greatly inferior force of French troops under Louis-Pierre Montbrun.[18]

On 21 April at dawn, Marshal Louis-Nicolas Davout moved his III Corps east from Haugen against Rosenberg's positions to open the two-day Battle of Eckmühl.[19] Suspecting an attack, Rosenberg put Stutterheim in command of three battalions, six squadrons, and a horse artillery battery and ordered him to hold the village of Paring, which is midway between Hausen and Eckmühl. At 6:00 AM Stutterheim reported the French advance and his corps commander reinforced him to a total of six battalions. The French division of Louis Friant soon attacked Paring with the 108th and 111th Line Infantry Regiments. While the 108th mounted a frontal assault, the 111th turned Austrian right flank. Paring fell and 400 Austrians were captured,[20] but the contest occupied the French until 11:00 AM. Meanwhile, Stutterheim's cavalry harassed the Bavarian division of Bernhard Erasmus von Deroy in its efforts to capture the town of Schierling to the west of Eckmühl. Deroy managed to wrest Schierling from Josef Philipp Vukassovich's defenders, but got no farther east that day.[21]

Stutterheim fell back east to the main line of defense, which ran through Unter- and Ober-Laichling. These twin villages are northwest of Eckmühl. Rosenberg posted Ludwig Alois von Hohenlohe-Bartenstein's division on the right, Sommariva's division in the center, and Stutterheim's advance guard on the left, holding a hill known as the Vorberg.[22] For the rest of the 21st, Davout battered at Rosenberg's line, but the Austrians managed to hold their ground until evening.[23]

That night at 2:00 AM, Stutterheim reported that Emperor Napoleon was about to attack the Austrian left flank. Archduke Charles planned for his right wing to attack Davout, while Rosenberg held his position on the left wing. The day of 22 April opened with a thick fog, which did not clear until after 8:00 AM. Charles did not issue his orders until that hour and intended for his troops to begin the assault on Davout about 1:00 PM.[24] The Austrian attack on Davout's left never materialized and Charles quickly abandoned the effort. Meanwhile, Napoleon arrived on the battlefield at about 2:00 PM. The emperor soon brought large forces to bear on Rosenberg's position from the south. Aware of his perilous position, Rosenberg refused his left flank to face the new threat.[25] Davout and Marshal François Joseph Lefebvre's Bavarian VII Corps attacked from the west, while Marshal Jean Lannes' provisional corps, consisting of two detached III Corps divisions, and Dominique Vandamme's Württemberg VIII Corps assaulted from the south.[26]

As the French and their German allies closed in on Rosenberg, Stutterheim led four squadrons of hussars in a charge which stopped the advance of some of Davout's troops near Unter-Laichling. Later, he directed four squadrons of Chevau-légers in a spirited counterattack against French skirmishers. These enemies, who threatened a key hill called the Bettel Berg, were driven off. Later, a division of French cuirassiers and German-allied cavalry approached the Bettel Berg. Stutterheim joined in a cavalry countercharge, but this time the Austrians were routed and most of the guns were captured when the hilltop was overrun.[27] At 9:00 AM on the morning of the 23rd, French cuirassiers attacked Stutterheim's rearguard and Charles sent an uhlan regiment to his assistance. This was the start of the Battle of Ratisbon.[28]

After the defeat at Eckmühl, the Austrian retreated into Bohemia.[29] On 29 April, Stutterheim led two cavalry regiments and a horse artillery battery from České Budějovice (Budweis) toward Linz, where he was to hold the bridge over the Danube.[30] Soon after, he operated on the north bank of the Danube in conjunction with Johann von Klenau's independent division.[31]

At the Battle of Aspern-Essling on 21 and 22 May, Stutterheim was put in charge of a light brigade in Johann Karl Peter Hennequin de Fresnel's division of Count Heinrich von Bellegarde's I Armeekorps. The brigade included the 2nd and 3rd Jäger Battalions, 10 squadrons of the Blankenstein Hussar Regiment Nr. 6, and a horse artillery battery. All told, there were 1,659 infantry, 1,039 cavalry, and six guns.[32] Still in Fresnel's I Armeekorps division, he led his brigade at the Battle of Wagram on 5 and 6 July. After a reorganization, the brigade was made up of the 2nd Jägers, eight squadrons of the Klenau Chevau-léger Regiment Nr. 5, and a cavalry battery. At Wagram his command numbered 743 infantry, 801 cavalry, and six guns.[33]

At 4:00 AM on 6 July, Stutterheim discovered that the village of Aderklaa had been evacuated by the Saxons. While Bellegarde failed to take advantage of this enemy miscue, Stutterheim rapidly occupied the village with three battalions and began to fortify it. When the French and Saxons tried to retake Aderklaa at 7:00 AM, he easily repelled the attack. But a second assault by Claude Carra Saint-Cyr's division a half-hour later proved to be more difficult to resist. After a grim resistance, the survivors of Stutterheim's 2,700-man command bolted for the rear. Archduke Charles quickly organized a counterattack by his second line troops, a grenadier brigade, and Stutterheim's rallied troops. Inspired by the archduke, the Austrians recaptured Aderklaa and seized the eagles of the 4th Line and 24th Light Infantry Regiments. Stutterheim was wounded during this fighting.[34] He received the Military Order of Maria Theresa on 24 October 1809.[1]

After his experiences in the 1809 campaign, he began work on his book, La Guerre de l'An 1809. He wrote the history through the fall of Vienna, but he became involved in a scandal and took his own life[35] on 13 December 1811, having never married. He was posthumously promoted to Feldmarschallleutnant.[1] The author Eugen Binder-Kriegelstein considered Stutterheim and Joseph Radetzky von Radetz the only Austrian generals who showed ability in the 1809 campaign.[36]

Notes[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f [1] Smith, Digby. Compiled by Leopold Kudrna. Bibliographical Dictionary of all Austrian Generals during the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars 1792-1815: Karl von Stutterheim

- ^ Smith, Digby. The Napoleonic Wars Data Book. London: Greenhill Books, 1998. ISBN 1-85367-276-9. 56

- ^ Arnold, James R. Marengo & Hohenlinden. Barnsley, South Yorkshire, UK: Pen & Sword, 2005. ISBN 1-84415-279-0. 68

- ^ Arnold Marengo, 70

- ^ Arnold Marengo, 71

- ^ Arnold Marengo, 72

- ^ Duffy, Christopher. Austerlitz 1805. Hamden, Conn.: Archon Books, 1977. 182

- ^ Smith, 216

- ^ Stutterheim, Karl von. Coffin, John Pine (trans.). A Detailed Account of the Battle of Austerlitz. London: T. Goddard, 1807. 81

- ^ Stutterheim, 82-83

- ^ Stutterheim, 83-84

- ^ Stutterheim, 85-87

- ^ Stutterheim, 87-88

- ^ Stutterheim, 118-119

- ^ Stutterheim, 121-127

- ^ Stutterheim, title page

- ^ Bowden, Scotty & Tarbox, Charlie. Armies on the Danube 1809. Arlington, Texas: Empire Games Press, 1980. 69

- ^ Petre, F. Loraine. Napoleon and the Archduke Charles. New York: Hippocrene Books, (1909) 1976. 110-112

- ^ Petre, 156

- ^ Petre, 158

- ^ Petre, 159

- ^ Petre, 160

- ^ Petre, 161-163

- ^ Petre, 170

- ^ Petre, 173

- ^ Bowden & Tarbox, 52

- ^ Petre, 177

- ^ Petre, 187

- ^ Arnold, James R. Napoleon Conquers Austria. Westport, Conn.: Praeger Publishers, 1995. ISBN 0-275-94694-0. 3

- ^ Petre, 212

- ^ Petre, 233, 246

- ^ Bowden & Tarbox, 89

- ^ Bowden & Tarbox, 163

- ^ Arnold Napoleon, 139-141

- ^ Arnold Napoleon, 240

- ^ Petre, 38

References[]

- Arnold, James R. Marengo & Hohenlinden. Barnsley, South Yorkshire, UK: Pen & Sword, 2005. ISBN 1-84415-279-0

- Arnold, James R. Napoleon Conquers Austria. Westport, Conn.: Praeger Publishers, 1995. ISBN 0-275-94694-0

- Bowden, Scotty & Tarbox, Charlie. Armies on the Danube 1809. Arlington, Texas: Empire Games Press, 1980.

- Duffy, Christopher. Austerlitz 1805. Hamden, Conn.: Archon Books, 1977.

- Petre, F. Loraine. Napoleon and the Archduke Charles. New York: Hippocrene Books, (1909) 1976.

- Smith, Digby. The Napoleonic Wars Data Book. London: Greenhill Books, 1998. ISBN 1-85367-276-9

- Smith, Digby. Compiled by Leopold Kudrna. Bibliographical Dictionary of all Austrian Generals during the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars 1792-1815: Karl von Stutterheim

- Stutterheim, Karl von. Coffin, John Pine (trans.). A Detailed Account of the Battle of Austerlitz. London: T. Goddard, 1807.

Other reading[]

- Arnold, James R. Crisis on the Danube. New York: Paragon House, 1990. ISBN 1-55778-137-0

- Austrian soldiers

- Austrian generals

- Prussian Army personnel

- Military personnel of Saxony

- Austrian Empire military personnel of the French Revolutionary Wars

- Austrian Empire commanders of the Napoleonic Wars

- Recipients of the Pour le Mérite (military class)

- 1770 births

- 1811 deaths