Kawésqar

Flag | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 3,448 (2017)[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Chile: Puerto Edén | |

| Languages | |

| Spanish, Kawésqar | |

| Religion | |

| Traditional tribal religion, Christian (mostly Protestant) | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Yaghan[citation needed] |

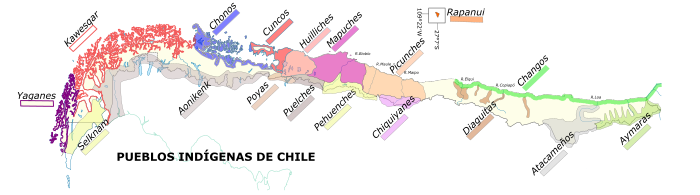

The Kawésqar, also known as the Alacalufe, Kaweskar, Alacaluf or Halakwulup, are an indigenous people who live in Chilean Patagonia, specifically in the Brunswick Peninsula, and Wellington, Santa Inés, and Desolación islands northwest of the Strait of Magellan and south of the Gulf of Penas. Their traditional language is known as Kawésqar; it is endangered as few native speakers survive.

Etymology[]

The English and other Europeans initially adopted the name that the Yaghan, a competing indigenous tribe whom they met first in central and southern Tierra del Fuego, used for these people: Alacaluf or Halakwulup (meaning "mussel eater" in the Yahgan language).[citation needed] Their own name for themselves (autonym) is Kawésqar.

Economy[]

Like the Yahgan in southern Chile and Argentina, the Kawésqar were a nomadic seafaring people, called canoe-people by some anthropologists. They made canoes that were eight to nine meters long and one meter wide, which would hold a family and its dog.[2] They continued this fishing, nomadic practice until the twentieth century, when they were moved into settlements on land. Because of their maritime culture, the Kawésqar have never farmed the land.

Population[]

The total population of the Kawésqar was estimated not to exceed 5,000. They ranged from the area between the Gulf of Penas (Golfo de Penas) to the north and the (Península de Brecknock) to the south.[2] Like other indigenous peoples, they suffered high fatalities from endemic European infectious diseases, to which they had no immunity. Their environment was disrupted as Europeans began to settle in the area in the late 1880s.

In the 1930s many remaining Alacaluf were relocated to Wellington Island, in the town of Puerto Edén, to shield them from pressures from the majority culture. Later they moved further south, to Puerto Natales and Punta Arenas.

In the 21st century, few Kawésqar remain. The 2002 census found 2,622 people identifying as Kawésqar (defined as those who still practiced their native culture or spoke their native language). In 2006, only 15 full-blooded members remained, but numerous mestizo have Kawésqar ancestry. Lessons in the Kawésqar language are part of the local curriculum, but few native speakers remain to encourage daily use of their traditional language. In 2021, Kawésqar activist Margarita Vargas López was elected to represent the nation in the Chilean Constitutional Convention.

Tribes and languages[]

Adwipliin, Aksánas, Alacaluf, Cálen (, Calenes), Caucahué, Enoo, , (Tayataf), Yequinahuere (Yequinahue, ).

By 1884 Thomas Bridges, an Anglican missionary based in Ushuaia who had been serving and studying the indigenous peoples of Tierra del Fuego since the late 1860s, and his son Despard compiled a 1200-word vocabulary for the Kawésqar language. It was in the form of a manuscript.[3] Through the late 19th and early 20th centuries, numerous missionaries and anthropologists moved among the indigenous peoples to aid, record and study them.

Kawéskar in human zoos[]

In 1881, European anthropologists took eleven Kawéskar people from Patagonia to be exhibited in the Bois de Boulogne in Paris, and in the Berlin Zoological Garden. Only four survived to return to Chile. Early in 2010, the remains of five of the seven who died in Europe were repatriated from the University of Zurich, Switzerland, where they had been held for studies. Upon the return of the remains, the president of Chile formally apologized for the state having allowed these indigenous people to be taken out of the country to be exhibited and treated like animals.[4]

See also[]

- Kawésqar language

- Alberto Achacaz Walakial, Kawésqar man who died in 2008

- Who Will Remember the People..., a 1986 novel by Jean Raspail about the history of the Alacalufe people

- The Pearl Button, a 2015 documentary film

References[]

- ^ "Síntesis de Resultados Censo 2017" (PDF). Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas, Santiago de Chile. p. 16.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Patricia Messier Loncuante, "Kawésqar Community" Archived 2012-08-07 at the Wayback Machine, National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution, accessed 12 October 2013

- ^ Furlong, Charles Wellington (December 1915). "The Haush And Ona, Primitive Tribes Of Tierra Del Fuego". Proceedings of the Nineteenth International Congress of Americanists: 446–447. Retrieved 2009-08-16.

- ^ "130 años después regresan los kawésqar", BBC.co.uk, January 2010

External links[]

- Patricia Messier Loncuante (2005). "Kawésqar Community". Indigenous Geography Project. National Museum of the American Indian. Archived from the original on 2012-08-07. Retrieved 2009-09-14.

- Los Alacalufes

- Los indios Alacalufes (o Kawésqar)

- Photo Gallery

- Indigenous peoples of the Southern Cone

- Ethnic groups in Chile

- Indigenous peoples in Tierra del Fuego

- Indigenous peoples in Chile

- Hunter-gatherers of South America

- Nomadic groups in the Americas

- Kawésqar