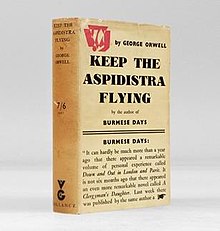

Keep the Aspidistra Flying

First edition | |

| Author | George Orwell |

|---|---|

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Genre | novel, social criticism |

| Set in | London, 1934 |

| Publisher | Victor Gollancz Ltd |

Publication date | 20 April 1936 |

| Media type | Print (hardback) |

| Pages | 318 (hardback) 248 (paperback) |

| OCLC | 1199526 |

| 823/.912 21 | |

| LC Class | PR6029.R8 K44 1999 |

| Preceded by | A Clergyman's Daughter |

| Followed by | The Road to Wigan Pier |

Keep the Aspidistra Flying, first published in 1936, is a socially critical novel by George Orwell. It is set in 1930s London. The main theme is Gordon Comstock's romantic ambition to defy worship of the money-god and status, and the dismal life that results in.

Background[]

Orwell wrote the book in 1934 and 1935, when he was living at various locations near Hampstead in London, and drew on his experiences in these and the preceding few years. At the beginning of 1928 he lived in lodgings in Portobello Road from where he started his tramping expeditions, sleeping rough and roaming the poorer parts of London.[1] At this time he wrote a fragment of a play in which the protagonist Stone needs money for a life-saving operation for his child. Stone would prefer to prostitute his wife rather than prostitute his artistic integrity by writing advertising copy.[2]

Orwell's early writings appeared in The Adelphi, a left-wing literary journal edited by Sir Richard Rees, a wealthy and idealistic baronet who made Orwell one of his protégés.[3] The character of Ravelston, the wealthy publisher in Keep the Aspidistra Flying, has a lot in common with Rees. Ravelston is acutely self-conscious about his upper-class status and defensive about his unearned income. Comstock speculates that Ravelston receives nearly two thousand pounds a year after tax—a very comfortable sum in those days—and Rees, in a volume of autobiography published in 1963, wrote: "I have never had the spending of much less than £1,000 a year of unearned income, and sometimes considerably more. ... Before the war, this was wealth, especially for an unmarried man. Many of my socialist and intellectual friends were paupers compared to me ..."[4] In quoting this, Orwell's biographer Michael Shelden comments that "One of these 'paupers'—at least in 1935—was Orwell, who was lucky if he made £200 that year. ... He appreciated Rees's editorial support at the Adelphi and sincerely enjoyed having him as a friend, but he could not have avoided feeling some degree of resentment toward a man who had no real job but who enjoyed an income four or five times greater than his."[5]

In 1932 Orwell took a job as a teacher in a small school in West London. From there he visited Burnham Beeches and other places in the countryside. There are allusions to Burnham Beeches and walks in the country in Orwell's correspondence at this time with Brenda Salkeld and Eleanor Jacques.[6]

In October 1934, after Orwell had spent nine months at his parents' home in Southwold, his aunt Nellie Limouzin found him a job as a part-time assistant in Booklovers' Corner, a second-hand bookshop in Hampstead run by Francis and Myfanwy Westrope. The Westropes, who were friends of Nellie in the Esperanto movement, had an easygoing outlook and provided Orwell with comfortable accommodation at Warwick Mansions, Pond Street. He was job sharing with Jon Kimche who also lived with the Westropes. Orwell worked at the shop in the afternoons, having the mornings free to write and the evenings to socialise.[7] He was at Booklovers' Corner for fifteen months. His essay "Bookshop Memories", published in November 1936, recalled aspects of his time at the bookshop, and in Keep the Aspidistra Flying "he described it, or revenged himself upon it, with acerbity and wit and spleen."[8] In their study of Orwell the writers Stansky & Abrahams remarked upon the improvement on the "stumbling attempts at female portraiture in his first two novels: the stereotyped Elizabeth Lackersteen in Burmese Days and the hapless Dorothy in A Clergyman's Daughter" and contended that, in contrast, "Rosemary is a credible female portrait". Through his work in the bookshop Orwell was in a position to become acquainted with women, "first as a clerk, then as a friend", and found that, "if circumstances were favourable, he might eventually embark upon a 'relationship' ... This, for Orwell the author and Blair the man, was the chief reward of working at Booklovers' Corner."[9] In particular, Orwell met Sally Jerome,[10] who was then working for an advertising agency (like Rosemary in Keep the Aspidistra Flying), and Kay Ekevall, who ran a small typing and secretarial service that did work for the Adelphi.[11]

By the end of February 1935 Orwell had moved into a flat in Parliament Hill; his landlady, Rosalind Obermeyer, was studying at the University of London. It was through a joint party with his landlady that Orwell met his future wife, Eileen O'Shaughnessy. In August Orwell moved into a flat in Kentish Town,[12] which he shared with Michael Sayers and Rayner Heppenstall. Over this period he was working on Keep the Aspidistra Flying, and had two novels, Burmese Days and A Clergyman's Daughter, published. At the beginning of 1936 Orwell was dealing with pre-publication issues for Keep the Aspidistra Flying while he was touring the North of England collecting material for The Road to Wigan Pier. The novel was published by Victor Gollancz Ltd on 20 April 1936.

Title[]

The aspidistra is a hardy, long-living plant that is used as a house plant in England, and which can grow to an impressive, even unwieldy size. It was especially popular in the Victorian era, in large part because it could tolerate not only weak sunlight but also the poor indoor air quality that resulted from the use of oil lamps and, later, coal gas lamps. They had fallen out of favour by the 20th century, following the advent of electric lighting. Their use had been so widespread among the middle class that they had become a music hall joke[13] appearing in songs such as "Biggest Aspidistra in the World," of which Gracie Fields made a recording.

In the titular phrase, Orwell uses the aspidistra, a symbol of the stuffiness of middle-class society, in conjunction with the locution "to keep the flag (or colours) flying."[14] The title can thus be interpreted as a sarcastic exhortation in the sense of "Hooray for the middle class!"

Orwell also used the phrase in his previous novel A Clergyman's Daughter, where a character sings the words to the tune of the German national anthem.[15]

In subsequent adaptions and translations, the original title has frequently been altered; in German, to "The Joys of the Aspidistra," in Spanish to "Don't Let the Aspidistra Die," in Italian to "May the Aspidistra Bloom." The 1997 movie adaptation was released in the United States as A Merry War.

"Keep the aspidistra flying!" is the final line of Nexus by Henry Miller. Orwell owned some of Miller's works while he was working at Booklovers' Corner. The books were banned in the U.K. at the time. (Nexus, however, was not one of them, as it was not published until several years after Orwell's death.)[16]

Plot summary[]

Gordon Comstock has 'declared war' on what he sees as an 'overarching dependence' on money by leaving a promising job as a copywriter for an advertising company called 'New Albion'—at which he shows great dexterity—and taking a low-paying job instead, ostensibly so he can write poetry. Coming from a respectable family background in which the inherited wealth has now become dissipated, Gordon resents having to work for a living. The 'war' (and the poetry), however, aren't going particularly well and, under the stress of his 'self-imposed exile' from affluence, Gordon has become absurd, petty and deeply neurotic.

Comstock lives without luxuries in a bedsit in London, which he affords by working in a small bookshop owned by a Scot, McKechnie. He works intermittently at a magnum opus he plans to call 'London Pleasures', describing a day in London; meanwhile, his only published work, a slim volume of poetry entitled Mice, collects dust on the remainder shelf. He is simultaneously content with his meagre existence and also disdainful of it. He lives without financial ambition and the need for a 'good job,' but his living conditions are uncomfortable and his job is boring.

Comstock is 'obsessed' by what he sees as a pervasion of money (the 'Money God', as he calls it) behind social relationships, feeling sure that women would find him more attractive if he were better off. At the beginning of the novel, he senses that his girlfriend Rosemary Waterlow, whom he met at New Albion and who continues to work there, is dissatisfied with him because of his poverty. An example of his financial embarrassment is when he is desperate for a pint of beer at his local pub, but has run out of pocket money and is ashamed to cadge a drink off his fellow lodger, Flaxman.

One of Comstock's last remaining friends, Philip Ravelston, a Marxist who publishes a magazine called Anti-Christ, agrees with Comstock in principle, but is comfortably well-off himself and this causes strains when the practical miseries of Comstock's life become apparent. He does, however, endeavour to publish some of Comstock's work and his efforts, unbeknownst to Comstock, had resulted in Mice being published via one of his publisher contacts.

Gordon and Rosemary have little time together—she works late and lives in a hostel, and his 'bitch of a landlady' forbids female visitors to her tenants. Then one evening, having headed southward and having been thinking about women—this women business in general, and Rosemary in particular—he happens to see Rosemary in a street market. Rosemary won't have sex with him but she wants to spend a Sunday with him, right out in the country, near Burnham Beeches. At their parting, as he takes the tram from Tottenham Court Road back to his bedsit, he is happy and feels that somehow it is agreed between them that Rosemary is going to be his mistress. However, what was intended as a pleasant day out away from London's grime turns into a disaster when, though hungry, they opt to pass by a 'rather low-looking' pub, and then, not able to find another pub, are forced to eat an unappetising lunch at a fancy, overpriced hotel. Gordon has to pay the bill with all the money he had set aside for their jaunt and worries about having to borrow money from Rosemary. Out in the countryside again, they are about to have sex for the first time when she violently pushes him back—he wasn't going to use contraception. He rails at her; "Money again, you see! ... You say you 'can't' have a baby. ... You mean you daren't; because you'd lose your job and I've got no money and all of us would starve."

Having sent a poem to an American publication, Gordon suddenly receives from them a cheque worth ten pounds—a considerable sum for him at the time. He intends to set aside half for his sister Julia, who has always been there to lend him money and support. He treats Rosemary and Ravelston to dinner, which begins well, but the evening deteriorates as it proceeds. Gordon, drunk, tries to force himself upon Rosemary but she angrily rebukes him and leaves. Gordon continues drinking, drags Ravelston with him to visit a pair of prostitutes, and ends up broke and in a police cell the next morning. He is guilt-ridden over the thought of being unable to pay his sister back the money he owes her, because his £5 note is gone, given to, or stolen by, one of the prostitutes.

Ravelston pays Gordon's fine after a brief appearance before the magistrate, but a reporter hears about the case, and writes about it in the local paper. The ensuing publicity results in Gordon losing his job at the bookshop, and, consequently, his relatively 'comfortable' lifestyle. As Gordon searches for another job, his life deteriorates, and his poetry stagnates. After living with his friend Ravelston, Gordon ends up working, this time in Lambeth, at another book shop and cheap two-penny lending library owned by the sinister Mr. Cheeseman, where he's paid an even smaller wage of 30 shillings a week. This is 10 shillings less than he was earning before, but Gordon is satisfied; "The job would do. There was no trouble about a job like this; no room for ambition, no effort, no hope." Determined to sink to the lowest level of society Gordon takes a furnished bed-sitting-room in a filthy alley parallel to Lambeth Cut. Both Julia and Rosemary, "in feminine league against him," seek to get Gordon to go back to his 'good' job at the New Albion advertising agency.

Rosemary, having avoided Gordon for some time, suddenly comes to visit him one day at his dismal lodgings. Despite his terrible poverty and shabbiness, they have sex but it is without any emotion or passion. Later, Rosemary drops in one day unexpectedly at the library, having not been in touch with Gordon for some time, and tells him that she is pregnant. Gordon is presented with the choice between leaving Rosemary to a life of social shame at the hands of her family—since both of them reject the idea of an abortion—or marrying her and returning to a life of respectability by taking back the job he once so deplored at the New Albion with its £4 weekly salary.

He chooses Rosemary and respectability and then experiences a feeling of relief at having abandoned his anti-money principles with such comparative ease. After two years of abject failure and poverty, he throws his poetic work 'London Pleasures' down a drain, marries Rosemary, resumes his advertising career, and plunges into a campaign to promote a new product to prevent foot odour. In his lonely walks around mean streets, aspidistras seem to appear in every lower-middle class window. As the book closes, Gordon wins an argument with Rosemary to install an aspidistra in their new small but comfortable flat off the Edgware Road.

Characters[]

- Gordon Comstock – a "well-educated and reasonably intelligent" young man possessed of a minor 'talent for writing'.

- Rosemary Waterlow – Comstock's girlfriend, whom he met at the advertising agency, who lives in a women's hostel and who has a forgiving nature, but about whom little else is revealed.

- Philip Ravelston – the wealthy left-wing publisher and editor of the magazine Antichrist who supports and encourages Comstock.

- Julia Comstock – Gordon's sister, who is as poor as he is and who, having always made sacrifices for him, continues to do so: "A tall, ungainly girl [–] her nature was simple and affectionate."

- Mrs. Wisbeach – landlady of the lodging house in Willowbed Road who imposes strict rules on her tenants, including Comstock.

- Mr Flaxman – Comstock's fellow lodger, a travelling salesman for the Queen of Sheba Toilet Requisites Co. who is temporarily separated from his wife.

- Mr McKechnie – the lazy, white-haired and white-bearded, teetotal and snuff-taking Scot who owns the first bookshop.

- Mr Cheeseman – the sinister and suspicious owner of the second bookshop.

- Mr Erskine – a large, slow-moving man with a broad, healthy, expressionless face who is the managing director of the advertising agency, the New Albion Publicity Company, and promotes Gordon to a position as a copywriter.

Extracts[]

No need to repeat the blasphemous comments which everyone who had known Gran'pa Comstock made on that last sentence. But it is worth pointing out that the chunk of granite on which it was inscribed weighed close on five tons and was quite certainly put there with the intention, though not the conscious intention, of making sure that Gran'pa Comstock shouldn't get up from underneath it. If you want to know what a dead man's relatives really think of him, a good rough test is the weight of his tombstone.

Gordon and his friends had quite an exciting time with their 'subversive ideas'. For a whole year they ran an unofficial monthly paper called the Bolshevik, duplicated with jellygraph. It advocated Socialism, free love, the dismemberment of the British Empire, the abolition of the Army and Navy, and so on and so forth. It was great fun. Every intelligent boy of sixteen is a Socialist. At that age one does not see the hook sticking out of the rather stodgy bait.

Gordon put his hand against the swing door. He even pushed it open a few inches. The warm fog of smoke and beer slipped through the crack. A familiar, reviving smell; nevertheless as he smelled it his nerve failed him. No! Impossible to go in. He turned away. He couldn't go shoving into that saloon bar with only fourpence halfpenny in his pocket. Never let other people buy your drinks for you! The first commandment of the moneyless. He made off down the dark pavement.

Hermione always yawned at the mention of Socialism, and refused even to read Antichrist. 'Don't talk to me about the lower classes,' she used to say. 'I hate them. They smell.' And Ravelston adored her.

This woman business! What a bore it is! What a pity we can't cut it right out, or at least be like the animals—minutes of ferocious lust and months of icy chastity. Take a cock pheasant, for example. He jumps up on the hen's backs without so much as a with your leave or by your leave. And no sooner is it over than the whole subject is out of his mind. He hardly even notices his hens any longer; he ignores them, or simply pecks them if they come too near his food.

Before, he had fought against the money code, and yet he had clung to his wretched remnant of decency. But now it was precisely from decency that he wanted to escape. He wanted to go down, deep down, into some world where decency no longer mattered; to cut the strings of his self-respect, to submerge himself—to sink, as Rosemary had said. It was all bound up in his mind with the thought of being under ground. He liked to think of the lost people, the under-ground people: tramps, beggars, criminals, prostitutes... He liked to think that beneath the world of money there is that great sluttish underworld where failure and success have no meaning; a sort of kingdom of ghosts where all are equal ... It comforted him somehow to think of the smoke-dim slums of South London sprawling on and on, a huge graceless wilderness where you could lose yourself forever.

Literary significance and criticism[]

Cyril Connolly wrote two reviews at the time of the novel's publication.[17] In the Daily Telegraph he described it as a "savage and bitter book", and wrote that "the truths which the author propounds are so disagreeable that one ends by dreading their mention."[18] In the New Statesman he wrote that it gave "a harrowing and stark account of poverty", and referred to its "clear and violent language, at times making the reader feel he is in a dentist's chair with the drill whirring".[19]

For an edition of the BBC Television show Omnibus, (The Road to the Left, broadcast 10 January 1971), Melvyn Bragg interviewed Norman Mailer. Bragg said he "just assumed Mailer had read Orwell. In fact he's mad on him." Of Keep the Aspidistra Flying Mailer said : "It is perfect from the first page to the last."[20]

Orwell wrote in a letter to George Woodcock dated 28 September 1946 that Keep the Aspidistra Flying was one of the two or three of his books that he was ashamed of because it "was written simply as an exercise and I oughtn't to have published it, but I was desperate for money. At that time I simply hadn't a book in me, but I was half starved and had to turn out something to bring in £100 or so."[21] Like A Clergyman's Daughter, Orwell did not want the book reprinted during his lifetime.[22] Orwell's biographer Jeffrey Meyers found the novel flawed by weaknesses in plot, style and characterisation, but praised "a poignant and moving quality that comes from Orwell's perceptive portrayal of the alienation and loneliness of poverty, and from Rosemary's tender response to Gordon's mean misery".[23] The novel has won other admirers besides Mailer, notably Lionel Trilling, who called it "a summa of all the criticisms of a commercial civilization that have ever been made".[24]

Tosco Fyvel, literary editor of Tribune from 1945 to 1949, and a friend and colleague of Orwell's during the last ten years of Orwell's life, found it interesting that "through Gordon Comstock Orwell expressed violent dislike of London's crowded life and mass advertising—a foretaste here of Nineteen Eighty-Four. Orwell has Gordon reacting to a poster saying Corner Table Enjoys His Meal With Bovex in a manner already suggesting that of the later novel:

"Gordon examined the thing with the intimacy of hatred.... Corner Table grins at you, seemingly optimistic, with a flash of false teeth. But what is behind the grin? Desolation, emptiness, prophecies of doom. —For can you not see [—] Behind that slick self-satisfaction, that tittering fat-bellied triviality, there's nothing but a frightful emptiness, a secret despair? And the reverberations of future wars."[25]

Catherine Blount pointed also to the theme of a London couple needing to go into the countryside in order to find a private place to have sex, which has a significant place in the plot of "Aspidistra" and which is taken up prominently in "Nineteen Eighty-Four".[26] Orwell biographer D. J. Taylor said of Comstock, "Like Dorothy in A Clergyman’s Daughter and like Winston Smith in Nineteen Eighty-Four, he rebels against the system and is ultimately swallowed up by it ... Like Winston Smith, he rebels, the rebellion fails, and he has to reach an accommodation with a world he’d previously disparaged".[22]

Film adaptation[]

A film adaptation of the same name was released in 1997. It, was directed by Robert Bierman, and stars Richard E. Grant and Helena Bonham Carter.[27] The film was released in North America and New Zealand under the alternative title of A Merry War.[28]

See also[]

References[]

- ^ Ruth Pitter BBC Overseas Service broadcast, 3 January 1956

- ^ Orwell Archive quoted in Bernard Crick Orwell: A Life Secker & Warburg 1980

- ^ Richard Rees George Orwell: Fugitive from the Camp of Victory Secker & Warburg 1961

- ^ Rees, Richard (1963). A Theory of My Time. An Essay in Didactic Reminiscence. London: Secker & Warburg. p. 64. Retrieved 12 April 2015.

- ^ Shelden, Michael (1991). Orwell: The Authorized Biography. New York: HarperCollins. p. 204. ISBN 978-0060167097. Retrieved 12 April 2015.

- ^ Eleanor Jacques Correspondence in Collected Essays Journalism and Letters, Secker & Warburg 1968

- ^ Rayner Heppenstall, "Four Absentees", in Audrey Coppard and Bernard Crick, eds, Orwell Remembered, 1984

- ^ Stansky & Abrahams, Orwell:The Transformation,p.73

- ^ Stansky & Abrahams, p.75

- ^ «Sally Jerome.» The Guardian. Retrieved 12 April 2015.

- ^ Stansky & Abrahams, Orwell:The Transformation,p.76, p.94

- ^ "George Orwell | Novelist | Blue Plaques".

- ^ Xenia Field Indoor Plants Hamlyn 1966

- ^ Cambridge Dictionary: keep the flag flying

- ^ "Chapter 3.1 - A Clergyman's Daughter - George Orwell, Book, etext". telelib.com. Retrieved 24 January 2020.

- ^ "Gordon Bowker: Orwell's Library". The Orwell Prize. 20 October 2010. Retrieved 7 February 2018.

- ^ Jeremy Lewis Cyril Connolly: A Life Jonathan Cape 1997

- ^ Daily Telegraph 21 April 1936

- ^ New Statesman 24 April 1936

- ^ Radio Times 9–15 January 1971

- ^ Orwell, Sonia and Angus, Ian (eds.). The Collected Essays, Journalism and Letters of George Orwell Volume 4: In Front of Your Nose (1945–1950) (Penguin)

- ^ Jump up to: a b Taylor, D. J. "The Best George Orwell Books". Five Books (Interview). Interviewed by Stephanie Kelley. Retrieved 30 October 2019.

- ^ A Readers Guide to Orwell, Jeffrey Meyers, p.87

- ^ Stansky & Abrahams, Orwell:The Transformation, p. 109

- ^ T R Fyvel, 'Orwell: A Personal Memoir', p.56

- ^ Catherine Blount, "Literary Representations of Changing 20th Century Sexual Mores", in Amalia Nicholson and Anibal Pearson (eds), "Was There a Sexual Revolution, and What Did It Consist Of?: A Multidisciplinary Round Table"

- ^ Elley, Derek (6 October 1997). "Keep the Aspidistra Flying". Variety.

- ^ "A Merry War". Rotten Tomatoes.com. Fandango Media. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

External links[]

- Keep the Aspidistra Flying at Faded Page (Canada)

- 1936 British novels

- British novels adapted into films

- Novels set in London

- Novels by George Orwell

- Novels about writers

- Books about landlords