Kenneth Mason (geographer)

Lieut-Colonel Kenneth Mason MC | |

|---|---|

Kenneth Mason | |

| Born | 10 September 1887 |

| Died | 2 June 1976 (aged 89) |

| Nationality | British |

| Alma mater | Royal Military Academy, Woolwich |

| Occupation | Soldier, explorer, Professor |

Lieut-Colonel Kenneth Mason MC (10 September 1887 – 2 June 1976) was a British soldier and geographer notable as the first statutory professor of Geography at the University of Oxford.[1] His work surveying the Himalayas was rewarded in 1927 with a Royal Geographical Society Founder's Medal, the citation reading for his connection between the surveys of India and Russian Turkestan, and his leadership of the Shaksgam Expedition.[2]

Personal life[]

Kenneth Mason was born at Sutton, Surrey, the son of Elizabeth Martin (née Turner) and Stanley Engledue Mason, a timber broker.[3] He was educated first at Cheltenham College and then the Royal Military Academy, Woolwich.[4]

Mason married Dorothy Helen Robinson in 1917 and they had two sons and one daughter.

Devoted to the Drapers' Company, Mason became its Master in 1949.

Military service[]

Mason was commissioned in the Royal Engineers. There, he helped to pioneer stereoscopic techniques that were to revolutionise cartography using aerial and land-based photogrammetry.

In 1914, Mason's First World War service took him to France (the Neuve Chapelle sector and Loos) before, in January 1916, he landed at Basra, Iraq. In action connected to the relief of Kut, he led a night march to the flank of the Dujailah redoubt, and was subsequently awarded the Military Cross. He entered Baghdad as Intelligence Officer with the Black Watch. He was promoted to Brevet-Major and three times mentioned in dispatches. Following the Armistice he was the first to take cars across the Syrian Desert.

Explorer[]

In 1909, Mason sailed for Karachi and was posted to the Survey of India. 1910-1912 saw him engaged on triangulation in Kashmir, where he learned climbing techniques, taught himself to ski and went on to make a stereographic land survey.

Mason returned to India after the First World War and began preparing for his most important scientific project, the exploration of the Shaksgam Valley, in 1926.[5] At that time the only westerner to see the valley had been Francis Younghusband, whose book The heart of a continent : a narrative of travels in Manchuria, across the Gobi Desert, through the Himalayas, the Pamirs, and Chitral, 1884-1894[6] had first inspired Mason as a schoolboy to pursue a career in geography. Now, Younghusband encouraged Mason to follow in his footsteps.

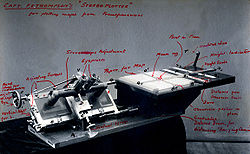

Through the 1920s, the interest of the British authorities had grown in the unmapped and uninhabited territories of the Shaksgam Valley because it provided access to the Aghil Pass linking China to Ladakh, India.[7] With support from the Royal Geographical Society (RGS), Mason began a survey using a photo-theodolite, laboriously collecting great quantities of data that represented the first attempt to apply stereographic techniques to both small scales and great distances. His results, plotted in Switzerland using what, at the time, was the world's most advanced Stereoplotter were acclaimed as brilliantly successful and won him the award of the 1927 RGS Founder's Gold Medal. While Mason had failed to fully descend the Shaksgam Valley he had been able to explore the Aghil range in the Karakoram fault system and discovered the valley of the Zug Shaksgam.

In 1928, Mason and Geoffrey Corbett convened a group to co-found The Himalayan Club, "To encourage and assist Himalayan travel and exploration, and to extend knowledge of the Himalaya and adjoining mountain ranges through science, art, literature and sport."[8] Mason edited the club's journal until 1940.

Mason's experiences of this period of his life in the British Raj were included in an oral history compiled by historian Charles Allen.[9] Meanwhile, his long association with the RGS, including serving on its council and as a vice-president, was to prove pivotal to the next step in his career.

Academic Geographer[]

The archives of Oxford University contain evidence that Geography was taught in several colleges since at least 1541.[10] However, the subject was given low priority until, in 1871, the Royal Geographical Society (RGS) made an approach that resulted in a Readership being established in 1887. Twelve years later, in 1899, a School of Geography was founded and a diploma course was introduced, with continuing financial support from the RGS, yet still the subject was not deemed of sufficient academic merit to warrant study for its own sake. It was not until 1932 that an Honours program was introduced and a statutory Chair of Geography was established associated with a Fellowship at Hertford College.[11] With support form the RGS, Mason was elected to the new chair, becoming the first statutory professor at the University of Oxford from 1 May 1932. His first task was to establish regulations for the new school which were published in 1932. The first Honour examinations were held the following year and by 1937 student numbers had reached 30 undergraduates.

Mason's academic work, linked to the Himalayan Journal which he had founded in 1929, addressed the challenge of naming ranges in the Karakoram region (specifically, the Baltoro Muztagh).[12][13]

In 1940 Mason was contacted by Ian Fleming (who later wrote the famous James Bond stories) and Rear Admiral John Henry Godfrey about the preparation of reports on the geography of countries involved in military operations. These reports were the precursors of the Naval Intelligence Division Geographical Handbook Series produced between 1941 and 1946. Mason directed a team of academics at Oxford who contributed around half of what was, at the time, one of the largest geographic projects ever attempted.[14]

Kenneth Mason retired from his chair at Oxford in 1953 but continued to write and give lectures on topics relating to the exploration of the Himalaya into his retirement.[15] His final major work, Abode of Snow: A History of Himalayan Exploration And Mountaineering,[16] was written shortly after the triumph of the 1953 British Mount Everest expedition and presents a comprehensive history of Himalayan exploration up to the first confirmed ascent of Mount Everest by Sir Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay.

Works[]

- Exploration of the Shaksgam Valley and Aghil Ranges, 1926 (1928)

- Routes in the Western Himalaya, Kashmir, & c. Vol. I Punch, Kashmir & Ladakh (1929)

- French West Africa British Naval Intelligence Division Geographical Handbook Series (1943)

- Italy British Naval Intelligence Division Geographical Handbook Series (1944)

- Iraq and the Persian Gulf British Naval Intelligence Division Geographical Handbook Series (1944)

- Western Arabia and the Red Sea British Naval Intelligence Division Geographical Handbook Series (1946)

- Abode of Snow (1955)

Mason also contributed obituaries for the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography for two fellow explorers:

References[]

- ^ "Mason, Kenneth (1887–1976), geographer and mountaineer". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Retrieved 16 September 2020.

- ^ "List of Past Gold Medal Winners" (PDF). Royal Geographical Society. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 24 August 2015.

- ^ Morris, J (3 June 1976). "In memoriam: Lieut-Colonel Kenneth Mason". The Times.

- ^ "Obituary: Kenneth Mason". The Geographical Journal. 142 (3): 566–567. November 1976.

- ^ Mason, Kenneth (1928). Exploration of the Shaksgam Valley and Aghil ranges, 1926. p. 72. ISBN 9788120617940.

- ^ Younghusband, Francis (1896). The heart of a continent : a narrative of travels in Manchuria, across the Gobi Desert, through the Himalayas, the Pamirs, and Chitral, 1884-1894. London: John Murray.

- ^ Westaway, Jonathan (2014). "That undisclosed world: Eric Shipton's Mountains of Tartary (1950)". Studies in Travel Writing.

- ^ Corbett, GL (1929). "The Founding of the Himalayan Club". The Himalayan Journal.

- ^ Allen, Charles (1988). Plain Tales from the Raj : Images of British India in the Twentieth Century. Time Warner Books.

- ^ Scargill, D.I. (January 1976). "The RGS and the Foundations of Geography at Oxford". Geographical Journal: 438–461.

- ^ "University and Educational Intelligence". Nature: 517. January 1932.

- ^ Muir Wood, Robert (6 November 1980). "Science Goes to the Karakorum". New Scientist: 374–377.

- ^ Mason, Kenneth (January 1930). "The Proposed Nomenclature of the Karakoram-Himalaya". Geographical Journal: 38–44.

- ^ Clout, Hugh; Gosme, Cyril (April 2003). "The Naval Intelligence Handbooks: a monument in geographical writing". Progress in Human Geography. 27 (2): 153–173 [156]. doi:10.1191/0309132503ph420oa. ISSN 0309-1325.

- ^ Mason, Kenneth (1956). "Great figures of nineteenth‐century Himalayan exploration". Journal of the Royal Central Asian Society: 167–175.

- ^ Mason, Kenneth (1954). Abode of Snow: A History of Himalayan Exploration And Mountaineering. Dutton.

- English geographers

- Graduates of the Royal Military Academy, Woolwich

- People educated at Cheltenham College

- 1887 births

- 1976 deaths

- Black Watch officers

- Royal Engineers officers

- British Army personnel of World War I

- Fellows of Hertford College, Oxford

- Statutory Professors of the University of Oxford

- British people in colonial India

- English surveyors