Kit Burns

Kit Burns | |

|---|---|

| Born | Christopher Keyburn February 23, 1831 |

| Died | December 19, 1870 (aged 39) South Brooklyn, New York, United States |

| Resting place | Calvary Cemetery |

| Nationality | Irish-American |

| Occupation | Saloon keeper |

| Known for | New York gang leader and underworld figure; he and Tommy Hadden co-led the Dead Rabbits during the 1850s. |

Christopher Keyburn (February 23, 1831 – December 19, 1870), commonly known by his alias Kit Burns, was an American sportsman, saloon keeper and underworld figure in New York City during the mid-to late 19th century, he and Tommy Hadden being the last-known leaders of the Dead Rabbits during the 1850s and 60s.

Burns also founded Sportsmen's Hall, also known as the Band Box, which served as a popular Bowery sporting resort and dance hall during this time. It was also a central meeting place for the New York underworld in the Bowery and old Fourth Ward areas for nearly two decades until it was finally closed following a campaign by ASPCA founder Henry Bergh in 1870.

Biography[]

Early life and the New York underworld[]

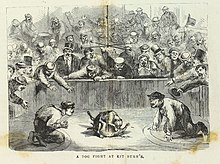

Born Christopher Keyburn in New York City on February 23, 1831, Burns joined the Dead Rabbits as a young man and, by the late 1840s, co-led the organization with Tommy Hadden. Both men started their own businesses in the Bowery with Burns opening his Sportsmen's Hall on Water Street.[1][2][3] His establishment was widely known for holding illegal bare-knuckle boxing prize fights as well as featuring such entertainment as the infamous "rat pit" where blood sports such as rat-baiting and dogfighting took place.[4][5][6] In these events, large gray wharf rats were captured and set against dogs. These dogs, mostly terriers, were sometimes starved for several days beforehand and set against each other as well.[1][3][7][8][9][10][11] Burns had two of his favorite dogs stuffed and mounted over the bar. The first, a black and tan colored terrier named Jack, reportedly set an American record by killing 100 rats in 6 minutes and 40 seconds. The other dog, Hunky, was a champion fighting dog "that expired after his last great victory".[12]

Sportsman's Hall occupied an entire three-story frame house, and the "rat pit" took up the first floor. The pit was described as being "arranged as an amphitheater, with rough wooden benches for seats. In the center was a ring enclosed by a wooden fence about three feet high."[8] His son-in-law Richard Toner, known as "Jack" or "Dick the Rat", would regularly bite the heads off rats; he would bite the head off a mouse for 10 cents and a wharf rat for a quarter.[3][13][14][15] Another Bowery character, "Snatchem" George Leese, served as the bouncer and official "bloodsucker" during prize fights, or more precisely, sucking the wounds of the participants to prevent blood loss and allow the fight to continue for as long as possible.[7][9][10]

The hall was especially popular in the city's underworld, not only in the Bowery but throughout Manhattan, and was referred to by James William Buel in Mysteries and Miseries of America's Great Cities (1883) as "an eating cancer on the body municipal, and within its crime begrimed walls have been enacted so many villainies, that the world has wondered why the wrath of vengeance did not consume it. But with all its festering and mephitic odors and criminalities, together with its votaries of Jezebel and Nana Sahib, the proprietor prospered and waxed rich. His rat and dog pits were known far and wide, and nowhere could the molochs and thugs find such delectable divertissement as Burns' pits afforded".[16] Behind the building was a small space, which reached through a narrow doorway that could be defended against a police raid, which was built to seat 250 people, but attendance often reached 400.[13][17]

Role in the Water Street revival[]

Burns was one of several saloon keepers targeted during the public crusade against John Allen, then called the "Wickedest Man in New York", and it was soon reported in the press that he and others had been "reformed" by religious leaders and agreed to hold prayer meetings in their establishments. Though he had declined their offers several times, he eventually allowed his "rat pit" to be used for a high fee.[8] It is claimed he rented out the building for one hour each week in exchange for $150.[1][18] One such meeting held at Sportsman's Hall in September 1868 was described by the New York World,

The Water Street prayer meetings are still continued. Yesterday at noon a large crowd assembled in Kit Burns' liquor shop, very few of whom were roughs. The majority seemed to be business men and clerks, who stopped in to see what was going on, in a casual manner. In a few minutes after twelve the pit was filled up very comfortably, and Mr. Van Meter made his appearance and took up a position where he could address the crowd from the center of the pit, inside the barriers. The roughs and dry clerks piled themselves up as high as the roof, tier by tier, and a sickening odor came from the dogs and debris of rats' bones under the seats.

Kit stood outside, cursing and damning the eyes of the missionaries for not hurrying up.

Kit said, "I'm damned if some of the people that come here oughtn't to be clubbed. A fellow 'ud think they had never seen a dogpit before. I must be damned good looking to have so many fine fellows looking at me."[7][9]

Burns later mocked the movement calling it "sheer humbug" and said, in reference to John Allen's holding an evangelical meeting in his establishment, "I've known Johnny Allen fourteen years and he couldn't be a pious man if he tried ever so hard. You might as well ask a rat to sing like a canary bird as to make a Christian out of that chap." The general public became skeptical of these meetings at the "rat pit", and a public inquiry was made to investigate the relationship between Burns and the missionaries. It was Burns himself, however, that was the first to turn against them. He and the other Water Street dive keepers were angry at having been paid less than half what John Allen had received.[1] One night, during a nightly meeting, he announced to reporters present that "them fellows have been making a pul-pit out of my rat pit and I'm going to purify it after them". Burns gave the signal and his barman began pelting the congregation of "ladies and clergymen" with rats while the regulars taunted the crowd with insults. Burns mandated a nightly show soon afterwards and "referred to his sacrament as one that 'ratified' the meetings". However, the hall operated a few weeks before the police shut the building down.[19]

Prompted by Henry Bergh, founder of the ASPCA, it was Burns' cruelty to animals that led to the final closing of Sportsman's Hall when it was raided on the night of November 31, 1870. It was recognized at the time as the city's largest dogfighting ring[20] and, that same night, Burns held his last event in the rat pit. He offered 300 rats to be "given away, free of charge, for gentlemen to try their dogs with". It was this advertisement that caught the attention of Bergh and who personally led the raid. Burns and all involved were arrested for violation of an anti-animal cruelty law passed by the New York state legislature four years prior.[12][21]

Death[]

Though everyone was acquitted at the trial, Burns caught a cold which developed into pneumonia and died on December 19, 1870, shortly before he was to go to trial. The funeral service at his South Brooklyn home was attended by "a motley crowd of young street urchins, grown-up rowdies, hard-faced men, 'sports' and women" who accompanied the funeral procession from Sackett Street to Calvary Cemetery where he was buried.[22] His Water Street establishment was carried on by his son-in-law Richard Toner and the English rat-catcher Jack Jennings, but they closed Burn's infamous "rat pit" and instead turned Sportsman's Hall, or the "Band-Box", into a full-time saloon. His widow later stated her intentions to apply to the common council, or Judge Joseph Dowling, for compensation when police disposed of a cage filled with rats in the East River in a recent raid ordered by Police Commissioner Bergh. She also wanted damages for a bullpup, valued at $100, which was also seized by police during the raid.[23]

Although little of the original structure remains, Sportsman's Hall occupied the land where the Joseph Rose House and Shop, a four-unit luxury apartment house, now lies and is the third oldest house in Manhattan after St. Paul's Chapel and the Morris-Jumel Mansion.[24][25]

In popular culture[]

Burns was referenced in the historical novels, Play For a Kingdom (1997) by Tom Dyja, A Universal History of Iniquity (2001) by Jorge Luis Borges and Lucky Billy (2008) by John Vernon; his character in the Borges' novel was confused with his son-in-law Jack the Rat, however.

References[]

- ^ a b c d Asbury, Herbert. All Around the Town: Murder, Scandal, Riot and Mayhem in Old New York. New York: Alfred A. Knoff, 1929. (pg. 126, 129-130) ISBN 1-56025-521-8

- ^ Moss, Frank. The American Metropolis from Knickerbocker Days to the Present Time. London: The Authors' Syndicate, 1897. (pg. 101)

- ^ a b c Batterberry, Michael. On the Town in New York: The Landmark History of Eating, Drinking, and Entertainments from the American Revolution to the Food Revolution. New York: Routledge, 1998. (pg. 104) ISBN 0-415-92020-5

- ^ Dillon, Richard H. Shanghaiing Days. New York: Coward-McCann, 1961. (pg. 244)

- ^ Turner, James. Reckoning With The Beast: Animals, Pain, and Humanity in the Victorian Mind. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University, 1980. (pg. 52) ISBN 0-8018-2399-4

- ^ De Andrade, Margarette. Water Under The Bridge. Rutland, Vermont: Charles E. Tuttle, 1988. (pg. 66) ISBN 0-8048-1430-9

- ^ a b c Asbury, Herbert. The Gangs of New York: An Informal History of the New York Underworld. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1928. (pg. 45-46, 53-55, 298) ISBN 1-56025-275-8

- ^ a b c Doutney, Thomas Narcisse. Thomas N. Doutney: His Life-Struggle, Fall, and Reformation, Also a Vivid Pen-Picture of New York, Together With a History of the Work He Has Accomplished as a Temperance Reformer. Boston: Rand Avery Company, 1887. (pg. 355-356, 358)

- ^ a b c Martin, Edward Winslow. The Secrets of the Great City: A Work Descriptive of the Virtues and the Vices, the Mysteries, Miseries and Crimes of New York City. Philadelphia: Jones Brothers & Co., 1868. (pg. 388-392)

- ^ a b Isenberg, Michael T. John L. Sullivan and His America. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1994. (pg. 84, 89, 96) ISBN 0-252-06434-8

- ^ Bettmann, Otto. The Good Old Days--They Were Terrible!. New York: Random House, 1974. (pg. 184) ISBN 0-394-70941-1

- ^ a b Burns, Patrick. American Working Terriers. Morrisville, North Carolina: Patrick Burns, 2006. (pg. 45-46) ISBN 1-4116-6082-X

- ^ a b Gems, Gerald R., Linda J. Borish and Gertrud Pfister. Sports in American History: From Colonization to Globalization. Champaign, Illinois: Human Kinetics, 2008. (pg. 156-157) ISBN 0-7360-5621-1

- ^ Ringenbach, Paul T. Tramps and Reformers, 1873-1916: The Discovery of Unemployment in New York. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1973. (pg. 85) ISBN 0-8371-6266-1

- ^ Chapman, John Wilbur. S. H. Hadley of Water Street: A Miracle of Grace. New York; Fleming H. Revell Company, 1906. (pg. 103)

- ^ Buel, James William. Mysteries and Miseries of America's Great Cities, Embracing New York, Washington City, San Francisco, Salt Lake City, and New Orleans. St. Louis and Philadelphia: Historical Publishing Co., 1883. (pg. 42, 45, 49)

- ^ Murrin, John M., Paul E. Johnson, James M. McPherson and Gary Gerstle. Liberty, Equality, Power: A History of the American People. 4th ed. Belmont, California: Thomas Wadsworth, 2008. (pg. 272) ISBN 0-495-56598-9

- ^ Sante, Lucy. Low Life: Lures and Snares of Old New York. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2003. (pg. 280) ISBN 0-374-52899-3

- ^ Dowling, Robert M. Slumming in New York: From the Waterfront to Mythic Harlem. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2008. (pg. 29-30) ISBN 0-252-07632-X

- ^ Beers, Diane L. For the Prevention of Cruelty: The History and Legacy of Animal Rights Activism in the United States. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press, 2006. (pg. 75-76) ISBN 0-8040-1087-0

- ^ Lane, Marion and Stephen Zawistowski. Heritage of Care: The American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group, 2008. (pg. 25) ISBN 0-275-99021-4

- ^ "Funeral of "Kit Burns."" (PDF). New York Times. 1870-12-24. Retrieved 31 August 2009.

- ^ "The "Band-Box" of the Late Kit Burns" (PDF). New York Times. 1871-01-02. Retrieved 31 August 2009.

- ^ Bunyan, Patrick. All Around the Town: Amazing Manhattan Facts and Curiosities. New York: Fordham University Press, 1999. (pg. 57) ISBN 0-8232-1941-0

- ^ Wolfe, Gerard R. New York, 15 Walking Tours: An Architectural Guide to the Metropolis. 3rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Professional, 2003. (pg. 49) ISBN 0-07-141185-2

Further reading[]

- Bonner, Arthur. Jerry McAuley and His Mission. Neptune, New Jersey: Loizeaux Bros., 1967.

- Kaufman, Martin and Herbert J. "Henry Bergh, Kit Burns, and the Sportsmen of New York." New York Folklore Quarterly. 28 (March 1972): 15-29.

- Tosches, Nick. King of the Jews: The Greatest Mob Story Never Told. New York: HarperCollins, 2006. ISBN 0-06-093600-2

- 1831 births

- 1870 deaths

- Criminals from New York City

- People from Manhattan

- People from Brooklyn