Koluvere Castle

| Koluvere Castle | |

|---|---|

Koluvere linnus | |

| Lääne County, Estonia | |

| |

| |

Koluvere Castle | |

| Coordinates | 58°54′20″N 24°06′15″E / 58.905602°N 24.104237°ECoordinates: 58°54′20″N 24°06′15″E / 58.905602°N 24.104237°E |

| Type | Castle |

| Site history | |

| Built | 13th century |

| Battles/wars | Battle of Lode (1573) |

| Garrison information | |

| Occupants | Reinhold von Buxhoeveden Duchess Augusta of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel |

Koluvere Castle (Estonian: Koluvere linnus; German: Schloss Lohde), also Koluvere Episcopal Castle, (Estonian: Koluvere piiskopilinnus), is a castle in Koluvere, Lääne County, in western Estonia.

History[]

A castle has existed on the strategic location since the 13th century. In 1439, it came into possession of the bishop of Saare-Lääne (German: Ösel-Wiek) and functioned as one of the main residences of the bishop.[1] During the Livonian War, a battle between an outnumbered Swedish army and a Russian army, resulting in a Swedish victory, was fought nearby. The clash, which took place in 1573, is known as the Battle of Lode. In 1560, insurgents during a peasant uprising reputedly also tried to storm the castle.[2]

Between 1646 and 1771, the castle belonged to the von Löwen family. By then it had lost its military significance and was henceforth used as an aristocratic residence. In 1771 it passed into the hands of Grigory Orlov after which it became the property of the Empress Catherine the Great. In 1786, the Empress found a use for the castle as a place of exile for Duchess Augusta of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel who had asked the Empress for protection from her violent husband, Prince Frederick of Würtemberg. She died at the estate under unclear circumstances, only 23 years old. Her grave is located in the nearby Kullamaa church, and her life has inspired plenty of local lore. In 1797, Emperor Paul I presented the estate as a gift to general Friedrich Wilhelm von Buxhoeveden. It remained in the possession of his heirs until 1919.[3][4][5]

Between 1924 and 2001, it was used by various welfare institutions.[6]

Architecture[]

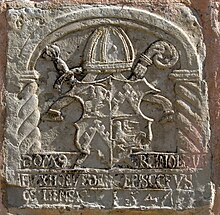

The castle is built on an artificial island created in a dammed up part of Liivi river. The high, square-shaped tower belongs to the oldest part of the castle and probably dates from the early 13th century, making it one of the oldest castle towers in Estonia. With the development of firearms, a large, round cannon-tower was added in the 16th century. From around this period a sculpted stone with the coat of arms of Reinhold von Buxhoeveden, bishop of Saare-Lääne 1532–1541 also dates.[7][8]

During the time of the ownership of the von Löwen family (et), the castle lost its military importance. It was instead converted into a comfortable home. Thus, in about 1770 the interior was extensively redecorated in Rococo style. Later, during the 19th century, the interiors received a neo-Gothic appearance.[9]

Several annexes to the main building were erected during its time as a manor house, for example stables and granaries, but also a noteworthy neo-Gothic power station. The surroundings were also transformed into a picturesque park with ponds, a pavilion and an arched bridge adorned with obelisks (19th century).[10][11]

Several fires have damaged the castle, notably in 1840, 1905 and 1963. Still, it remains a very fine example of castle architecture in Estonia.[12][13][14]

See also[]

- History of Estonia

- Bishopric of Ösel–Wiek

- Battle of Lode

- Duchess Augusta of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel

- List of castles in Estonia

References[]

- ^ Hein, Ants (2009). Eesti Mõisad - Herrenhäuser in Estland - Estonian Manor Houses. Tallinn: Tänapäev. p. 103. ISBN 978-9985-62-765-5.

- ^ Viirand, Tiiu (2004). Estonia. Cultural Tourism. Kunst Publishers. p. 107. ISBN 9949-407-18-4.

- ^ Hein, Ants (2009). Eesti Mõisad - Herrenhäuser in Estland - Estonian Manor Houses. Tallinn: Tänapäev. p. 103. ISBN 978-9985-62-765-5.

- ^ Viirand, Tiiu (2004). Estonia. Cultural Tourism. Kunst Publishers. pp. 107–108. ISBN 9949-407-18-4.

- ^ Sakk, Ivar (2004). Estonian Manors - A Travelogue. Tallinn: Sakk & Sakk OÜ. pp. 308–309. ISBN 9949-10-117-4.

- ^ Hein, Ants (2009). Eesti Mõisad - Herrenhäuser in Estland - Estonian Manor Houses. Tallinn: Tänapäev. p. 103. ISBN 978-9985-62-765-5.

- ^ Viirand, Tiiu (2004). Estonia. Cultural Tourism. Kunst Publishers. pp. 107–108. ISBN 9949-407-18-4.

- ^ Sakk, Ivar (2004). Estonian Manors - A Travelogue. Tallinn: Sakk & Sakk OÜ. pp. 308–309. ISBN 9949-10-117-4.

- ^ Sakk, Ivar (2004). Estonian Manors - A Travelogue. Tallinn: Sakk & Sakk OÜ. pp. 308–309. ISBN 9949-10-117-4.

- ^ Viirand, Tiiu (2004). Estonia. Cultural Tourism. Kunst Publishers. pp. 107–108. ISBN 9949-407-18-4.

- ^ Sakk, Ivar (2004). Estonian Manors - A Travelogue. Tallinn: Sakk & Sakk OÜ. pp. 308–309. ISBN 9949-10-117-4.

- ^ Hein, Ants (2009). Eesti Mõisad - Herrenhäuser in Estland - Estonian Manor Houses. Tallinn: Tänapäev. p. 103. ISBN 978-9985-62-765-5.

- ^ Viirand, Tiiu (2004). Estonia. Cultural Tourism. Kunst Publishers. pp. 107–108. ISBN 9949-407-18-4.

- ^ Sakk, Ivar (2004). Estonian Manors - A Travelogue. Tallinn: Sakk & Sakk OÜ. pp. 308–309. ISBN 9949-10-117-4.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Koluvere Castle. |

- Official website

- Old official website (in Estonian)

- Koluvere Manor at Estonian Manors Portal

- Castles in Estonia

- Lääne-Nigula Parish

- Buildings and structures in Lääne County

- Gothic architecture in Estonia

- Tourist attractions in Lääne County