Korean beauty standards

This article has multiple issues. Please help or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

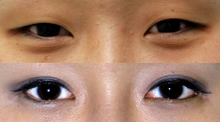

Korean beauty standards have become a well-known feature of Korean culture. In 2015, a global survey by the International Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgeons placed South Korea in the top ten of countries who had the highest rate of cosmetic surgeries.[1] Korean beauty standards prioritize a slim figure, small face, v-shaped jaw, pale skin, straight eyebrows, flawless skin, and larger eyes. Beauty standards for the eyes include aegyo-sal, which is a term used in Korea referring to the small fatty deposits underneath the eyes that are said to give a person a more youthful appearance. East Asian blepharoplasty is a surgery to create double eyelids (creates upper eyelid with a crease) which makes the eyes appear larger. Korean beauty standards have been influenced largely by those in the media, including actresses, TV personalities, and K-pop stars. The physical appearance of K-pop idols has greatly impacted the beauty standards in Korea.[2]

Cultural pressure[]

A study from 2008 determined that 20 percent of young Korean girls have undergone cosmetic surgery. This is significantly above the average rate in other countries.[3] A more recent survey from Gallup Korea in 2015 determined that approximately one-third of South Korean women between 19 and 29 have claimed to have had plastic surgery.[4] A study from 2009 found that Korean women are very critical of their body image and are more prone to lower self-esteem and self-satisfaction compared to women from the United States.[5]

In South Korea, there is immense societal pressure to conform to the community and societal expectations placed on the individual. This is evident in the theorization of what influences both Korean men and women to want to strive to achieve a strict beauty standard. A study by Lin and Raval from Miami University shows that the pressure for the "perfect" appearance may stem from feelings of inferiority from the community if they perceive themselves as less attractive.[6] The result from this particular study supports the previous evidence from Keong Ja Woo, who analyzed how beauty standards in Korea, in regard to one’s height, weight, and facial preference, impacted their chances of employment.[7]

The pressure to uphold a standard of beauty is even felt within the job market. Companies require a photo, height, and sometimes the family background of applicants as a part of the hiring process.[8] Beauty is often seen as a means for socioeconomic success in the rapidly modernized post-war economy of South Korea, which has seen a sluggish job growth rate after its economic boom. This has left Korea with a highly skilled and educated workforce competing for a short supply of job opportunities and chances for upward social mobility. Some Koreans view investments in beauty, such as cosmetic products and medical beauty treatments, such as plastic surgery, dermatology, and cosmetic dentistry, as a means of cultural capital to get an edge over peers for social and economic advancement.[9]

Although the theorization of the impact of Western beauty standards for the Korean society is highly controversial, there has been convincing data which demonstrates this effect. There are rigid expectations for South Korean women to have large eyes and a thin, high nose bridge which is arguably a trait that is representative of Caucasian women.[10] In addition to this, Jung and Lee observed that there were more models that conformed to more Caucasian features in South Korean magazines than that of U.S. magazines.[11] Countless studies depict the unfortunate psychosocial impact of these beauty standards that adhere to Western features as South Korean women were found to have a higher risk of body dysmorphia, dislike for their body, higher likelihood of eating disorders which were accompanied by depression, low self-esteem, and stress.[6]

In addition, since South Korea has seen more than a twenty-fold increase in real per capita income and is currently ranked within the top twenty economies in the world with continual growth, there has been a paralleled increase in visibility for women's rights within the country.[12] However, with this growth in visibility and social change for women, there is an interesting observation that this change is "immediately accompanied by increases in body dissatisfaction and eating disorders".[12] This could be explained by a sociocultural theory, namely objectification theory, that asserts:

"Any movement toward gender equality that threatens the stability of the patriarchy is followed inevitably by a heightened emphasis on unrealistic beauty standards and increasing pressure to meet these standards. Such pressure may be effectively applied as a means to oppress women and maintain patriarchal control, as unrealistic standards such as these undermine women's self-confidence and materially shift their focus away from their individual capabilities to more generalized and superficial aspects of their physical appearance."[13]

Other cultural factors such as the hardened Confucianism in Korean society has been quoted as a prominent factor. Majority of the Confucius philosophy created the gender roles and norms in Korea, which some of his teachings has been sustained even through modern Korea. The emphasis on gender roles, with women being submissive and men being dominant, caused a patriarchal society from these philosophical teachings which may have had an impact on the beauty standard.[10] Women are more likely to examine and make changes to their bodies and face in order to adhere to the beauty standards projected by the objectification theory that views women as "objects".[13] This raises the observation that impractical beauty standards could be caused by highly patriarchal societies that only promote unbending gender roles which is then reflected by the influence of Confucianism in Korean history. There could be another cultural factor such as certain facial features leading to bad luck encourages the Korean individual to plastic surgery.[6]

Beauty products[]

In 2015 South Korea exported more than $2.64 billion of cosmetic goods[14] compared to around $1.91 billion in 2014.[15] Some of the most popular products used in Korean beauty are blemish balm (BB) creams, color correction (CC) creams, serums, essences, ampoules, seaweed face masks, and scrubs.[16] Korean beauty products contain ingredients not commonly found in Western products such as snail extract. In 2011, BB cream, which was previously only found in China, hit the shelves in America, and by 2014, the US market for BB cream was around $164 million.

Plastic surgery[]

Plastic surgery in South Korea is not stigmatized and is even a common graduation gift.[17] The appeal of East Asian blepharoplasty, the most common cosmetic procedure in South Korea, is largely attributed to the influence of Western culture. Western beauty ideals extend beyond the eyes to face shape. As individuals of East Asian descent often have a flatter facial bone structure (in comparison to those of European descent), facial bone contouring surgeries are also quite popular.[18] V-line surgery (jaw and chin reduction) and cheekbone (zygoma) reduction surgeries are used to change the facial contour. These surgeries are especially common amongst celebrities who are often required to undergo these changes in their cheekbones, jaw, and chin with the ultimate goal being to create an oval face.

Motivation for plastic surgery has been debated throughout Korean society. Holliday and Elfving-Hwang suggest that the pressure of success in work and marriage is deeply rooted in the one's ability to manage their body which is influenced by beauty.[19] As companies helping with matchmaking for marriage and even job applications require a photo of the individual, it is inevitable that the Korean population feels pressure to undergo plastic surgery to achieve the "natural beauty".[6]

South Korea has also seen an increase in medical tourism from people who seek surgeon expertise in facial bone contouring. Korean surgeons have advanced facial bone contouring with procedures like the osteotomy technique[20][21] and have published the first book on facial bone contouring surgeries.[22] There was a 17 percent increase in the sales of cosmetic surgery from 1999 to 2000, reaching almost ₩170 billion (South Korean won) which is $144 million US dollars.[23]

History[]

David Ralph Millard, who graduated from Yale College and Harvard Medical School, had been employed by the U.S. Marine Corps as the chief plastic surgeon in South Korea.[24] Desiring a similar path to his mentor, Sir Harold Gillies, he wanted to provide reconstructive plastic surgery for wounded soldiers, children, and other civilians that were injured by the Korean War. Millard was observing ways to perform reconstructive surgeries on burn victims in order to reforming eyebrows on the patients in which he had an unusual interest to the study of the eye, the eye socket, and the eyelid fold.[24]

He wanted to modify the structure of the "oriental" eye into a more "western" look. Millard was unable to find a consenting patient until a Korean translator requested undergo the operation for eyes that had a more "round appearance", stating that the "because of the squint in his slant eyes, Americans could not tell what he was thinking and consequently did not trust him" in which Millard agreed with his sentiment.[24] Millard then found inspiration to pave the way to conduct his own research on performing double-eyelid surgery when he could not find any journals translated in English.

Although the double-eyelid surgery was already performed in small bulks in Japan, Hong Kong, and Korea, Millard's incorporation had changed the motivation and techniques for plastic surgery in Korea. Millard stated he wanted to reduce the "Asian-ness" by making a higher nose bridge by implanting more cartilage to the nose and widening the eyes by tearing the inner fold of the eye for a look of a longer eye, removed the fat in the eyelid that causes the monolid, and sutured the skin on the eyelid to create the double-eyelid fold.[24] There were many plastic surgeries of this nature performed on various Koreans during this era and before he left the country, trained numerous local doctors on his techniques.

Free the corset movement[]

After the #MeToo movement, when women shared their sexual assault and harassment stories, Korean women started to question their beauty standards and created the free the corset movement. Its name comes from the idea that societal oppression of women is like being bound in a corset. Korean women have taken to social media in a backlash against unrealistic beauty standards that requires them to spend hours applying makeup and performing extensive skincare regimes, which often involve ten steps or more.[25] Some Korean women have destroyed their makeup, cut their hair, and rejected the pressures of getting surgery.[25][26] The purpose of the movement is to create space for Korean women to feel comfortable with themselves and not have social pressures limit their identity.[27] Critics of the movement think that women can make their own choices to wear makeup or not.[28]

Male beauty standards[]

While expectations of female beauty usually outweigh male expectations, South Korea is notable for the standards placed on men. South Korea has become one of the beauty capitals of the world for male beauty. Dissimilar to the West, it is still a misconception that the South Korean beauty industry exclusively focuses on women. Make-up is not seen as a gendered product and South Korea itself is proud to advertise many brands and products that are available to men. One of the reasons for this standard is the Korean Pop music culture or K-Pop. In the Western hemisphere, the population has a different understanding when it comes to the attractiveness of males.

It is very common for Korean men to care about a clear, smooth and fair skin. It is also usual to dye and style hair on regular basis.[29] The body shape is expected to appear rather androgyne than too muscular. Men wear sharply stylish cut outfits and double eyelids are really common as a result of cosmetic surgery. Korean men often choose to get surgery to achieve a higher nose along with smaller and slender facial features.[30]

"Over the past decade South Korean men have become the world's biggest male spenders on skincare and beauty products." Between 2011 and 2017, the market grew by 44%.[31] South Koreas's cosmetics industry earns nearly $10 billion in annual sales. The industry is trying to expand its appeal to young men in their twenties. The cosmetic companies' marketing teams have also developed strategies to win new costumers for their always changing product lines. Major sports events such as baseball games air advertisements for skincare due to the large attendance of potential customers making it a good commercial opportunity to do so.

In a country where military service is mandatory for all men, even this is used to lure prospective costumer. A South Korean-based company has released a line of face paint for active duty soldiers that include tealeaf extract to soothe and cool the skin.[32]

The general Western conception of males wearing make-up could be mistaken as an act of rebellion against the society rather than a beauty standard. Nevertheless, this seems to be changing due to the influence of Korean beauty standards not only because of K-Pop's "perfect brows and flawless skin",[31] which is one of the new beauty standards even for the west.

References[]

- ^ "ISAPS International Survey on Aesthetic/Cosmetic Procedures Performed in 2015 | isaps.org" (PDF). isaps org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 August 2017. Retrieved 4 August 2017.

- ^ "Unrealistic Beauty Standards: Korea's Cosmetic Obsession". seoulbeats.com. 26 March 2015. Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- ^ Holliday, Ruth; Elfving-Hwang, Joanna (1 June 2012). "Gender, Globalization and Aesthetic Surgery in South Korea". Body & Society. 18 (2): 58–81. doi:10.1177/1357034X12440828. ISSN 1357-034X. S2CID 146609517.

- ^ "Meet the South Korean women rejecting intense beauty standards". South China Morning Post. Associated Press. 5 February 2019. Retrieved 22 May 2019.

- ^ Jung, J. (2006). "Cross-Cultural Comparisons of Appearance Self-Schema, Body Image, Self-Esteem, and Dieting Behavior Between Korean and U.S. Women". Family and Consumer Sciences Research Journal. 34 (4): 350–365. doi:10.1177/1077727X06286419.

- ^ a b c d Lin, K. L., & Raval, V. V. (2020). Understanding Body Image and Appearance Management Behaviors among Adult Women in South Korea within a Sociocultural Context: A Review. International Perspectives in Psychology: Research, Practice, Consultation, 9(2), 96–122.

- ^ Woo, K. J. (2004). The Beauty Complex and the Plastic Surgery Industry. Korea Journal, 44, 52– 82.

- ^ Maguire, Ciaran. "Stress dominates every aspect of life in South Korea". The Irish Times. Retrieved 24 October 2016.

- ^ "Why is plastic surgery so popular in South Korea?". My Seoul Secret - Korean Plastic Surgery Trip Advisor. 26 October 2017. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- ^ a b Jung, J., Forbes, G. B., & Lee, Y. (2009). Body Dissatisfaction and Disordered Eating among Early Adolescents from Korea and the U.S. Sex Roles, 61, 42–54.

- ^ Jung, J., & Lee, Y. J. (2009). Cross-cultural Examination of Women's Fashion and Beauty Magazine Advertisements in the United States and South Korea. Clothing and Textiles Research Journal, 27, 274–286.

- ^ a b Kim, S. Y., Seo, Y. S., & Baek, K. Y. (2014). Face consciousness among South Korean women: A culture-specific extension of objectification theory. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 61(1), 24–36. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034433

- ^ a b Fredrickson, B. L., & Roberts, T. (1997). Objectification theory: Toward understanding women's lived experiences and mental health risks. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 21, 173–206. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.1997.tb00108.x

- ^ Service (KOCIS), Korean Culture and Information. "Korean skincare, cosmetics exports hit USD 2.6 bil. : Korea.net : The official website of the Republic of Korea". www.korea.net. Retrieved 28 January 2019.

- ^ Arthur, Golda (28 January 2016). "The key ingredients of South Korea's skincare success". BBC News. Retrieved 11 April 2017.

- ^ "Asian Beauty Standards and Products Make Way for Innovation and Influence Markets in the West". go.galegroup.com. Retrieved 11 April 2017.

- ^ Marx, Patricia. "The World Capital of Plastic Surgery". The New Yorker. Retrieved 21 June 2021.

- ^ Park, Sanghoon (14 June 2017), "Why Facial Bone Contouring Surgery?: Backgrounds", Facial Bone Contouring Surgery, Springer Singapore, pp. 3–6, doi:10.1007/978-981-10-2726-0_1, ISBN 9789811027253

- ^ Holliday, R., & Elfving-Hwang, J. (2012). Gender, Globalization and Aesthetic Surgery in South Korea. Body and Society, 18, 58– 81.

- ^ Lee, Tae Sung; Kim, Hye Young; Kim, Tak Ho; Lee, Ji Hyuck; Park, Sanghoon (March 2014). "Contouring of the Lower Face by a Novel Method of Narrowing and Lengthening Genioplasty". Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 133 (3): 274e–282e. doi:10.1097/01.prs.0000438054.21634.4a. ISSN 0032-1052. PMID 24572871. S2CID 2679583.

- ^ Lee, Tae Sung; Kim, Hye Young; Kim, Takho; Lee, Ji Hyuck; Park, Sanghoon (October 2014). "Importance of the Chin in Achieving a Feminine Lower Face". The Journal of Craniofacial Surgery. 25 (6): 2180–3. doi:10.1097/scs.0000000000001096. ISSN 1049-2275. PMID 25329849. S2CID 27463104.

- ^ Facial bone contouring surgery : a practical guide. Park, Sanghoon. Singapore: Springer. 2017. ISBN 9789811027260. OCLC 1004601615.CS1 maint: others (link)

- ^ Ja, Woo Keong (2004). "The beauty complex and the cosmetic surgery industr". Korea Journal. 44 (2): 52.

- ^ a b c d Kurek, L. (2015). Eyes Wide Cut: The American Origins of Korea's Plastic Surgery Craze: South Korea's Obsession with Cosmetic Surgery can be traced back to an American Doctor, Raising Uneasy Questions about Beauty Standards. The Wilson Quarterly, 39(4).

- ^ a b Pressigny, Clementine de; Chan, Keira (30 October 2018). "why a new generation of women are challenging south korea's beauty standards".

- ^ Alejo, Aubrey (28 November 2018). "Koreans Are Ditching Beauty Standards to Escape The Corset". MEGA.

- ^ "A corset-free movement". Korea JoongAng Daily.

- ^ Bizwire, Korea. ""Free Corset" Movement Gathers Steam".

- ^ Balen, Cara. "Gendered Beauty: How South Korea is challenging our perception of male beauty standards". London Runaway. Retrieved 13 February 2019.

- ^ B., Elsa. "What are the beauty standards for men in South Korea?". Kpopstarz. Retrieved 4 June 2014.

- ^ a b The Thaiger. "Will the West embrace the South Korean male beauty product industry?". The Thaiger. Retrieved 25 January 2019.

- ^ Shim, Elizabeth. "South Korean men buying into cosmetics craze, wearing makeup to improve image". UPI NewsTrack. Retrieved 11 May 2015.

- Interpersonal attraction

- Korean culture

- Physical attractiveness