Kushwaha

| Kushwaha | |

|---|---|

| Religions | Hinduism |

| Languages |

|

| Country | India Nepal Mauritius |

| Populated states | Bihar • Uttar Pradesh |

| Region | Eastern India |

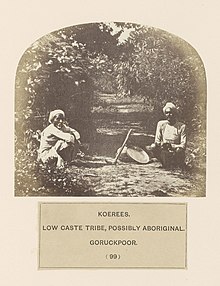

Kushwaha (sometimes, Kushvaha)[1] is a community of the Indo-Gangetic Plain which has traditionally been involved in agriculture (including beekeeping).[2] The term has been used to represent at least four subcastes, being those of the Kachhis, Kachwahas, Koeris and Muraos. They claim descent from the mythological Suryavansh (Solar) dynasty via Kusha, who was one of the twin sons of Rama and Sita. Previously, they had worshipped Shiva and Shakta.

Origin

The Kushwaha claim descent from the Suryavansh dynasty through Kusha, a son of the mythological Rama, an avatar of Vishnu, a myth of origin developed in the twentieth century. Prior to that time, the various branches that form the Kushwaha community - the Kachhis, Kachwahas, Koeris, and Muraos - favoured a connection with Shiva and Shakta.[3] Ganga Prasad Gupta, a proponent of Kushwaha sanskritization, claimed in the 1920s that Kushwaha families worshiped Hanuman - described by Pinch as "the embodiment of true devotion to Ram and Sita" - during Kartika, a month in the Hindu lunar calendar.[4]

Demographics and distribution

William Pinch notes a Kushwaha presence in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar,[3] and they are also recorded in Haryana.[5] Outside India, they are found in the Terai of Nepal, where they have variously been officially recorded as Kushwaha and as Koiri.[6] They also have significant presence among Bihari diaspora in Mauritius. The migration of Biharis to neighbouring countries was a phenomenon which became more pronounced in the post independence India. Thus, small island nations like Mauritius has significant population of people of Indian origin. The tradition and culture of Hindu migrants in countries like Mauritius is quite different from Indian subcontinent. This is so with varna status and "social hierarchy" as both these terms have several variation in Mauritius vis a vis India. The traditional ruling elites like Rajputs and Brahmins are politically and economically marginalised on the island while cultivating castes like Koeri, Ahir, Kurmi, Kahar and others have improved their social and financial position.[7] According to Crispin Bates:

The Vaish are the largest and most influential caste group on the island. Internally the group is divided into Koeri, Kurmi, Kahar, Ahir, Lohar and other jatis. In the past many admitted to Chamar status (as shown by historical records), but recently this seems to have become completely taboo. This group, now commonly known as 'Rajputs', will also sometimes describe themselves as 'Raviveds.' An explanation may lie in the rapid economic growth of the 1980s and 1990s, as well as the lack of positive discrimination measures of the sort seen in India.[7]

Economy

According to Arun Sinha, the Koeris were known for their market gardening activities. Since Indian independence, the land reform movement was making it difficult for the erstwhile upper-caste landlords to maintain their existing holdings. The growing pressure from left-wing militants backed by CPI(ML) and some local political parties, as well as the weakening of the Zamindari system was making it difficult for them to survive in the rural areas. Hence, the decades following independence were marked by the urbanization of upper castes. Their migration to cities was accompanied by selling off of their unproductive holdings, which were mostly bought by the peasants of cultivating middle castes, who were financially sound enough to purchase land. Some of the land was also bought from Muslim families who were migrating to Pakistan. The Koeris, along with Kurmis and Yadavs were the main buyers of these lands.[8]

However, since the peasant castes considered their land to be their most productive asset, they rarely sold it. The zeal of peasant castes to buy more and more land gradually changed their economic profile, and some of them became 'neo-landlords'. This transformation caused them to attempt to protect their new economic status from those below them, especially the Dalits, who were still mainly landless labourers. Thus they adopted many of the practices of their erstwhile landlords.[8] The pattern of land reform in states like Bihar which mainly benefitted the middle castes like those of Koeris was also responsible for the imperfect mobilisation of backward castes in the politics. The space carved by backwards in electoral politics after 1967 was dominated mainly by these middle peasant castes and they were the biggest beneficiary of the politics of socialism, the proponent of which were people like Ram Manohar Lohia.[9] The unequitable political space at the disposal of other Backward Castes and Scheduled Castes was thus an implicit implication of these land reforms as according to Varinder Grover:

The pattern of land reforms in Bihar is one of the main reason for imperfect mobilisation of backward castes into the politics. The abolition of all intermediaries had definitely helped the hard working castes like Kurmi, Koeris and Yadav. These small peasant proprietors worked very hard on their land and also drive their labourers hard, and any resistance by agricultural labourers gives rise to the mutual conflicts and atrocities on Harijans.[10]

The differences between upper backward castes and the extremely backward castes and Dalits due to unequal distribution of the benefits of land reforms was thus a major challenge before the CPI(ML) in mobilisation of collective force of lower castes against the upper caste landlords. The upper backward castes like Koeri were initially less attached to the CPI(ML) due to their economic progress and the communists were successful in mobilising them only in some regions like Patna, Bhojpur, Aurangabad and Rohtas district. These success were attributed to the widespread dacoity and oppressive attitude of the upper caste landlords faced by these hardworking caste groups which propelled them to join the fold of revolutionary organisations.[11]

Political presence

The Kushwaha also engaged in political action during these latter days of the Raj. Around 1933–1934,[a] the Koeris joined with the Kurmis and Yadavs to form the Triveni Sangh, a caste federation that by 1936 claimed to have a million supporters. This coalition followed an alliance for the 1930 local elections which fared badly at the polls. The new grouping had little electoral success: it won a few seats in the 1937 elections but was stymied by a two-pronged opposition which saw the rival Congress wooing some of its more wealthy leading lights to a newly formed unit called the "Backward Class Federation" and an effective opposition from upper castes organised to keep the lower castes in their customary place. Added to this, the three putatively allied castes were unable to set aside their communal rivalries and the Triveni Sangh also faced competition from the All India Kisan Sabha, a peasant-oriented socio-political campaigning group run by the Communists. The appeal of the Triveni Sangh had waned significantly by 1947[13][14] but had achieved a measure of success away from the ballot box, notably by exerting sufficient influence to bring an end to the begar system of forced unpaid labour and by providing a platform for those voices seeking reservation of jobs in government for people who were not upper castes.[15] Many years later, in 1965, there was an abortive attempt to revive the defunct federation.[16]

The Kisan Sabha was dominated by peasant castes like the Koeri, Kurmi and Yadav, which led some historians such as Gyan Pandey to term them mainly movements of the middle peasant castes who organized against bedakhil (eviction), with limited participation of other communities. The reality, however, was more complex. Dalit communities like the Chamars and Pasis, whose traditional occupations were leatherwork and toddy-tapping respectively, formed a significant portion of the landless peasantry and were thus significant in the Kisan Sabha, and present were even members of the high castes such as Brahmins.[17]

The Koeris also had significant presence in the Naxalite movement of 1960's rural Bihar, particularly in Bhojpur and nearby areas like Arrah, where an economic system dominated by the upper caste landlords was still in place.[18] For the lower castes, the issue was not merely economic but it was the question of Ijjat (honour), since upper caste men often raped lower-caste women with impunity. Here, the Communist upsurge against the prevalent feudal system was led by Jagdish Mahto, a Koeri teacher who had read Ambedkar and Marx and was sympathetic to the cause of Dalits.[19]

According to Santosh Singh, the Bhumihars of the region beat him mercilessly when he was found voicing support for CPI in upcoming elections. After Mahto was discharged from the hospital he formed his own militant outfit with the help of his associates Ram Naresh Ram and Rameswar Ahir. Mahto's organisation was affiliated to Communist Party of India (Marxist–Leninist), a radical faction of Communist Party of India. Mahto led his militia, which assassinated many upper-caste landlords in the region, until he was killed during a police raid. However, the action of Jagdish clearly demarcated the dividing lines between Koeris and Bhumihars in the Ekwaari.[19][20]

For much of the 20th century, the Koeries were generally less politically effective, even less involved, than the Kurmis and Yadavs who broadly shared their socio-economic position in Hindu society. The latter two groups were more vociferous in their actions, including involvement in caste rioting, whilst the Koeris had only a brief prominence during the ascendancy of Jagdeo Prasad. This muted position changed dramatically in the 1990s when the rise to power of Lalu Prasad in Bihar caused an assertion of Yadav-centric policies that demanded a loud reaction.[21]

Earlier, the Koeris were given fair representation in Laloo Yadav as well as Rabri Devi regime. The backward politics unleashed by Laloo Prasad resulted in rise to political prominence of numerous backward castes, among which Koeri were prominent.[21] In this period, caste remained the most effective tool of political mobilisation and even leaders who were theoretically against caste-based politics also appealed to caste loyalties to secure their victory. The Rabri Devi government had appointed ten Koeris as minister in her cabinet, which was sought by many community leaders as a fair representation to the clan.[22] The portrayal of Laloo Yadav as a "Messiah of backward castes" lost the ground when the Yadav ascendancy in politics led other aspirational backward castes to move away from his party. In the meantime during 1990s, Nitish Kumar, who was projected as the leader of Kurmi and Koeri communities formed the Samta Party, leading to the isolation of Koeri-Kurmi community from Yadavs and Laloo Prasad.[21][23]

Thus, the decades following independence witnessed a complete shift of power from upper castes to the "upper backward castes": a term coined to describe castes like the Koeri, Yadav, Kurmi and Bania in Bihar. The transfer of power was also witnessed at the local level of governance. The upper caste were first to acquire education and they benefitted from it initially but with the expansion in electoral franchise and growth of "party system", they lost the ground to upper backward communities. Nepotism and patronage for fellow caste members in government, which had previously been an upper-caste phenomenon, was now available to the upper backward communities. This phenomenon continued with Karpoori Thakur in the 1970s, who had provided 12% reservation to lower backward castes and 8% to upper backwards in which Koeri were included. The peak of this patronage was reached during the tenure of Laloo Yadav.[23]

From 1990 onwards the solidarity of backward castes was severely weakened due to division among the Koeri-Kurmi community and Yadavs. The former's voting pattern was in quite contrast to that of the latter. When Samta Party allied with the Bhartiya Janata Party, Koeris voted for this alliance and thus in 1996 Lok Sabha elections BJP fared well, primarily with the support of Koeri and Kurmis. The division among backwards also costed their representation in the assemblies. It was seen that profile of Bihar legislative assembly was changing rapidly since 1967 and till 1995-96 the representation of upper caste was reduced to as lower as 17%. But, the division among backwards served as a hope to the upper castes to at least increase their representation. The success of BJP-Samta coalition however also consolidated the Koeris and the Kurmis, who now emerged as political force in 1996 elections.[24]

Since 1996 the Koeris voted en masse for the JD (U) and BJP coalition. The caste based polarisation in states like Bihar drifted the dominant backward castes away from the Rashtriya Janata Dal and distributed their votes to various political parties. The Koeris who constituted one of the most populous caste group were shifted first towards JD (U)-BJP coalition. Later after the expulsion of Upendra Kushwaha from the JD (U) and formation of Rashtriya Lok Samata Party, their votes were distributed amongst the JD (U) on the one hand and the new social coalition made by BJP with Lok Janshakti Party and Rashtriya Lok Samata Party on the other hand.[25] In 2015 Bihar Legislative Assembly elections the Janata Dal (United) allied with its rival Rashtriya Janata Dal due to differences with Bhartiya Janata Party. The social composition of these parties and the core voter base are such that this coalition drew immense support from the Yadav, Kurmi and Kushwaha caste who hardly voted together after the 1990s. Consequently, the coalition emerged with massive victory with the number of legislators from these agrarian castes reaching higher as compared to previous elections.[26] Later the coalition was ripped apart and in 2020 Assembly elections the disunity among the three castes and split of votes led to huge decline in number of Kushwaha legislators.[27]

Culture and beliefs

In the central Bihar backward castes like Koeri are numerically and politically powerful and hence they reject the traditional Jajmani system which relies upon Brahmanical notion of purity and pollution.[28] The backward caste groups in this region thus do not avail the services of Brahmin priests to perform their rituals. In most of the cases, Koeri households employ a Koeri priest to perform their rituals and their services are also availed by other backward castes like Yadav. These priest who belong to Koeri caste are different from the Brahmin priests in their approval of widow remarriage. They also promote non-vegetarianism and do not grow tuft like the Brahmins. The tika (liquid form of sandalwood on the head) which is made by the Brahmin priests on their forehead is also disapproved by them.[29]

Classification

Disputed varna status

The Kushwaha were traditionally a peasant community and considered to be of the Shudra varna.[30] Pinch describes them as "skilled agriculturalists".[31] The traditional perception of Shudra status was increasingly challenged during the later decades of British Raj rule, although various castes had made claims of a higher status well before the British administration instituted its first census.[b] The Kurmi community of cultivators, described by Christophe Jaffrelot as "middle caste peasants", led this charge in search of greater respectability.[13] Pinch describes that "The concern with personal dignity, community identity, and caste status reached a peak among Kurmi, Yadav, and Kushvaha peasants in the first four decades of the twentieth century."[33]

Identification as Kushwaha Kshatriya

From around 1910, the Kachhis and the Koeris, both of whom for much of the preceding century had close links with the British as a consequence of their favoured role in the cultivation of the opium poppy, began to identify themselves as Kushwaha Kshatriya.[34] An organisation claiming to represent those two groups and the Muraos petitioned for official recognition as being of the Kshatriya varna in 1928.[35]

This action by the All India Kushwaha Kshatriya Mahasabha (AIKKM) reflected the general trend for social upliftment by communities that had traditionally been classified as being Shudra. The process, which M. N. Srinivas called sanskritisation,[36] was a feature of late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century caste politics.[35][37]

The position of the AIKKM was based on the concept of Vaishnavism, which promoted the worship and claims of descent from Rama or Krishna as a means to assume the trappings of Kshatriya symbolism and thus permit the wearing of the sacred thread even though the physical labour inherent in their cultivator occupations intrinsically defined them as Shudra. The movement caused them to abandon their claims to be descended from Shiva in favour of the alternate myth that claimed descent from Rama.[38] In 1921, Ganga Prasad Gupta, a proponent of Kushwaha Sanskritization, had published a book offering proof of the Kshatriya status of the Koeri, Kachhi, Murao and Kachwaha.[31][39] His reconstructed history argued that the Kushwaha were Hindu descendants of Kush and that in the twelfth century they had served Raja Jaichand in a military capacity during the period of Muslim consolidation of the Delhi Sultanate. Subsequent persecution by the victorious Muslims caused the Kushwaha to disperse and disguise their identity, foregoing the sacred thread and thereby becoming degraded and taking on various localised community names.[31] Gupta's attempt to prove Kshatriya status, in common with similar attempts by others to establish histories of various castes, was spread via the caste associations, which Dipankar Gupta describes as providing a link between the "urban, politically literate elite" members of a caste and the "less literate villagers".[40] Some communities also constructed temples in support of these claims as, for example, did the Muraos in Ayodhya.[4]

Some Kushwaha reformers also argued, in a similar vein to Kurmi reformer Devi Prasad Sinha Chaudhari, that since Rajputs, Bhumihars and Brahmins worked the fields in some areas, there was no rational basis for assertions that such labour marked a community as being of the Shudra varna.[41]

William Pinch describes the growth of militancy among agricultural castes in the wake of their claims to Kshatriya status. Castes like Koeris, Kurmis and Yadavs asserted their Kshatriya status not merely by words but they joined the British Indian Army as soldiers in large number. The growing militancy among them turned rural Bihar into an arena of conflict in which numerous caste-based militias surfaced and atrocities against the Dalits became the new norm. The militias founded during this period were named after folk figures or popular personalities who were revered by the whole community.[42]

Classification as Backward Caste

Kushwahas are classified as a Most Backward Caste (MBC) in some of the states of India.[43][44] In 2013, the Haryana government added the Kushwaha, Koeri and Maurya castes to the list of backward classes.[5] In Bihar they are categorized as Other Backward Class.[45] The various subcastes of Kushwaha community viz Kachhi, Shakya and Koeri are categorized as OBC in Uttar Pradesh also.[46]

References

Notes

- ^ The date of formation of the Triveni Sangh has been variously stated. Some sources have said it was the 1920s but Kumar notes recently discovered documentation that makes 1933 more likely,[12] whilst Jaffrelot has said 1934.[13]

- ^ William Pinch records that, "... a popular concern with status predated the rise of an imperial census apparatus and the colonial obsession with caste. ... [C]laims to personal and community dignity appeared to be part of a longer discourse that did not require European political and administrative structures."[32]

Citations

- ^ Pinch, William R. (1996). Peasants and monks in British India. University of California Press. p. 91. ISBN 978-0-520-20061-6.

- ^ Harper, Malcolm (2010). Inclusive Value Chains: A Pathway Out of Poverty. World Scientific. pp. 182, 297. ISBN 978-981-4293-89-1.

- ^ a b Pinch, William R. (1996). Peasants and monks in British India. University of California Press. pp. 12, 91–92. ISBN 978-0-520-20061-6.

- ^ a b Pinch, William R. (1996). Peasants and monks in British India. University of California Press. p. 98. ISBN 978-0-520-20061-6.

- ^ a b "Three castes included in backward classes list". Hindustan Times. 5 November 2013. Archived from the original on 15 April 2014. Retrieved 14 April 2014.

- ^ Mandal, Monika (2013). Social Inclusion of Ethnic Communities in Contemporary Nepal. KW Publishers. pp. 109–110. ISBN 978-93-81904-58-9.

- ^ a b Bates, Crispin (2016). Community, Empire and Migration: South Asians in Diaspora. Springer. p. 14. ISBN 978-0333977293. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- ^ a b Sinha, A. (2011). Nitish Kumar and the Rise of Bihar. Viking. pp. 80–84. ISBN 978-0-670-08459-3. Retrieved 7 April 2015.

- ^ Kumar, Sanjay (5 June 2018). Post mandal politics in Bihar:Changing electoral patterns. SAGE publication. p. 55. ISBN 978-93-528-0585-3.

- ^ Verinder Grover (1997). "Political system and constitution of India". Indian Political System: Trends and Challenges, Volume 10. Deep and Deep Publications. pp. 780–781. ISBN 8171008844. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

- ^ Ranabir Samaddar (3 March 2016). "Bihar 1990-2011". Government of Peace: Social Governance, Security and the Problematic of Peace. Routledge, 2016. p. 178. ISBN 978-1317125372. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

- ^ Kumar, Ashwani (2008). Community Warriors: State, Peasants and Caste Armies in Bihar. Anthem Press. pp. 43, 196. ISBN 978-1-84331-709-8.

- ^ a b c Jaffrelot, Christophe (2003). India's silent revolution: the rise of the lower castes in North India (Reprinted ed.). C. Hurst & Co. pp. 197–198. ISBN 978-1-85065-670-8.

- ^ Kumar, Ashwani (2008). Community Warriors: State, Peasants and Caste Armies in Bihar. Anthem Press. p. 44. ISBN 978-1-84331-709-8.

- ^ Kumar, Ashwani (2008). Community Warriors: State, Peasants and Caste Armies in Bihar. Anthem Press. p. 36. ISBN 978-1-84331-709-8.

- ^ Kumar, Ashwani (2008). Community Warriors: State, Peasants and Caste Armies in Bihar. Anthem Press. p. 62. ISBN 978-1-84331-709-8.

- ^ Rawat, Ramnarayan S. (2011). Reconsidering Untouchability: Chamars and Dalit History in North India. Indiana University Press. pp. 12–15. ISBN 978-0-25322-262-6.

- ^ Ahmed, Suroor. "Bihar-seat-sharing-amit-shah-had-no-time-to-meet-kushwaha-rlsp-leaders-upset". National Herald. Retrieved 3 August 2020.

- ^ a b Omvedt, Gail (1993). Reinventing Revolution: New Social Movements and the Socialist Tradition in India. M.E.Sharpe. p. 59. ISBN 0765631768. Retrieved 16 June 2020.^ Its first mass leader was Jagdish Mahto, a koeri teacher who had read ambedkar before he discovered Marx and started a paper in the town of arrah called Harijanistan("dalit land")..

- ^ Singh, Santosh (2015). Ruled or Misruled: Story and Destiny of Bihar. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-9385436420. Retrieved 19 July 2020.

- ^ a b c Kumar, Ashwani (2008). Community Warriors: State, Peasants and Caste Armies in Bihar. Anthem Press. pp. 34–37. ISBN 978-1-84331-709-8.

- ^ Sondhi, M. L. (2001). Towards a New Era: Economic, Social and Political Reforms. Har-Anand Publications. ISBN 8124108005. Retrieved 19 July 2020.

- ^ a b Thakur, Baleshwar (2007). City, Society, and Planning: Society. University of Akron. Department of Geography & Planning, Association of American Geographers: Concept Publishing Company. pp. 393–400. ISBN 978-8180694608. Retrieved 16 June 2020. While Samta with its leader Nitish is considered to be the party of Koeri-Kurmi, Bihar people's party led by Anand Mohan is perceived to be a party having sympathy and support of Rajputs.

- ^ Shah, Ghanshyam (2004). Caste and Democratic Politics in India. Orient Blackswan. pp. 346, 350–354. ISBN 8178240955. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- ^ Suhas Palshikar; Sanjay Kumar; Sanjay Lodha (2017). "7. The eastern gift, BJP's 2014 victory in Bihar". Electoral Politics in India: The Resurgence of the Bharatiya Janata Party. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1351996914. Retrieved 3 October 2020.

- ^ "Which Caste Holds Key to Nitish's Return as CM? Here's the Data". The Quint. Retrieved 24 November 2020.

- ^ "One in every four new Bihar assembly members is from upper castes". Times of India. Archived from the original on 29 January 2021. Retrieved 24 November 2020.

- ^ Dipankar Gupta (2004). Caste in Question: Identity Or Hierarchy?. SAGE Publications India. ISBN 8132103459. Retrieved 9 October 2020.

- ^ Partha Nath Mukherji; N. Jayaram; Bhola Nath Ghosh (2019). Understanding Social Dynamics in South Asia: Essays in Memory of Ramkrishna Mukherjee. Springer. p. 97. ISBN 978-9811303876. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- ^ Pinch, William R. (1996). Peasants and monks in British India. University of California Press. p. 81. ISBN 978-0-520-20061-6.

- ^ a b c Pinch, William R. (1996). Peasants and monks in British India. University of California Press. p. 92. ISBN 978-0-520-20061-6.

- ^ Pinch, William R. (1996). Peasants and monks in British India. University of California Press. p. 88. ISBN 978-0-520-20061-6.

- ^ Pinch, William R. (1996). Peasants and monks in British India. University of California Press. pp. 83–84. ISBN 978-0-520-20061-6.

- ^ Pinch, William R. (1996). Peasants and monks in British India. University of California Press. p. 90. ISBN 978-0-520-20061-6.

- ^ a b Jaffrelot, Christophe (2003). India's silent revolution: the rise of the lower castes in North India (Reprinted ed.). C. Hurst & Co. p. 199. ISBN 978-1-85065-670-8.

- ^ Charsley, S. (1998). "Sanskritization: The Career of an Anthropological Theory". Contributions to Indian Sociology. 32 (2): 527. doi:10.1177/006996679803200216. S2CID 143948468.

- ^ Upadhyay, Vijay S.; Pandey, Gaya (1993). History of anthropological thought. Concept Publishing Company. p. 436. ISBN 978-81-7022-492-1.

- ^ Jassal, Smita Tewari (2001). Daughters of the earth: women and land in Uttar Pradesh. Technical Publications. pp. 51–53. ISBN 978-81-7304-375-8.

- ^ Narayan, Badri (2009). Fascinating Hindutva: saffron politics and Dalit mobilisation. SAGE. p. 25. ISBN 978-81-7829-906-8.

- ^ Gupta, Dipankar (2004). Caste in question: identity or hierarchy?. SAGE. p. 199. ISBN 978-0-7619-3324-3.

- ^ Pinch, William R. (1996). Peasants and monks in British India. University of California Press. p. 110. ISBN 978-0-520-20061-6.

- ^ kunnath, George (2018). Rebels From the Mud Houses: Dalits and the Making of the Maoist Revolution... New york: Taylor and Francis group. p. 209,210. ISBN 978-1-138-09955-5. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- ^ "17 Most Backward Castes May Play Kingmaker as Purvanchal Gears Up to Vote in Final Phase". News18. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- ^ "Upper castes rule Cabinet, backwards MoS". The Times of India. 27 May 2014. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

- ^ "Central list of backward castes (Bihar)". scbc.bih.nic. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- ^ "Central list of OBC (Uttar Pradesh)". ncbc.nic.in. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

Further reading

- Alf Gunvald Nilsen, Kenneth Bo Nielsen (23 November 2016). Social Movements and the State in India: Deepening Democracy?. Springer. p. 2016. ISBN 978-1137591333. Retrieved 19 July 2020.

- Samaddar, Ranbir (2019). From popular movement to rebellion:The Naxalite dacade. New york: Routledge. p. 317,318. ISBN 978-0-367-13466-2. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- Agricultural castes

- Shaktism

- Social groups of Bihar

- Social groups of Uttar Pradesh

- Suryavansha

- Vaishnavism