Lancaster Town Hall

| Lancaster Town Hall | |

|---|---|

Lancaster Town Hall | |

| Location | Dalton Square, Lancaster |

| Coordinates | 54°02′50″N 2°47′52″W / 54.0471°N 2.7977°WCoordinates: 54°02′50″N 2°47′52″W / 54.0471°N 2.7977°W |

| Built | 1909 |

| Architect | Edward Mountford and Thomas Lucas |

| Architectural style(s) | Edwardian Baroque style |

Listed Building – Grade II* | |

| Designated | 22 December 1953 |

| Reference no. | 1194923 |

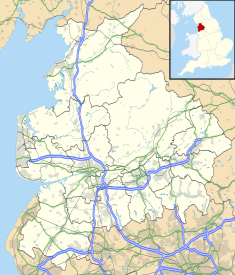

Shown in Lancashire | |

Lancaster Town Hall is a municipal building in Dalton Square, Lancaster, Lancashire, England. It is a Grade II* listed building.[1]

History[]

The building was commissioned to replace the aging town hall, now the city museum, in Market Square.[2] The new building was designed by Edward Mountford and Thomas Lucas in the Edwardian Baroque style and the stonework, furniture and carvings were undertaken by Waring & Gillow.[1] The carvings on the front pediment were sculpted by F. W. Pomeroy and the stained glass windows were manufactured by Shrigley and Hunt.[2]

The facility accommodated a police station in the basement and a magistrates' court on the ground floor[3] and it included an assembly hall, to the rear of the main building, which became known as the "Ashton Hall".[2] The concert organ in the Ashton Hall was designed and built by Norman and Beard for the hall in time for its opening.[4] The whole complex, as well as the Queen Victoria Memorial in Dalton Square, had been personally financed by Lord Ashton who officially opened the facility on 27 December 1909.[5][6]

A war memorial, designed by Thomas Mawson & Sons together with the Bromsgrove School of Art and sculpted by Morton of Cheltenham, was unveiled by the mayor, George Jackson,[7] in a memorial garden adjacent to the town hall, on 3 December 1924.[8] Queen Elizabeth II, accompanied by the Duke of Edinburgh, visited the town hall in her new capacity as Duke of Lancaster on 13 April 1955.[9][10]

Highly publicised cases to come before the courtroom on the ground floor of the town hall included the initial stages of the trial of Dr Buck Ruxton, who in 1935, was accused of murdering both his wife and his housemaid.[11]

The town hall became the headquarters of Municipal Borough of Lancaster on completion but following the amalgamation of the Municipal Borough of Lancaster with the Municipal Borough of Morecambe and Heysham in 1974, meetings of the full council of the City of Lancaster have been held in Morecambe Town Hall.[2]

In May 1995 Priory Records released a recording from the Ashton Hall entitled Lancastrian Organ Gems which involved excerpts of music composed by Felix Mendelssohn, Malcolm Archer and Henry Smart performed by Malcolm Archer on the concert organ.[12]

Episode 14 of series 28 of the Antiques Roadshow, which was broadcast on 14 March 2014, was filmed in the Ashton Hall within the complex.[13]

The Magistrates' Court had moved to a new building in 1985, but the old Magistrates' Court within the Town Hall was brought back into use as an emergency 'Nightingale Court' during the 2020-2021 COVID-19 pandemic. [14] The Ashton Hall was similarly used as an emergency Crown Court. [15]

References[]

- ^ a b Historic England. "Town Hall, Lancaster (1194923)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- ^ a b c d "History of Lancaster Town Hall". City of Lancaster. Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- ^ "Lancaster Town Hall". AJ Buildings Library. Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- ^ "Across the Pennines to Lancaster" (PDF). The Pipeline. 6 June 2014. p. 8. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- ^ "Obituary: Lord Ashton – A Wealthy Recluse". The Times. 28 May 1930. p. 18.

- ^ Farrer, William; Brownbill, J. (1914). "'Townships: Lancaster', in A History of the County of Lancaster". London: British History Online. pp. 33–48. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- ^ "Former mayors of the City of Lancaster". City of Lancaster. Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- ^ "Lancaster". Imperial War Museum. Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- ^ "Royalty - Queen Elizabeth II - Lancaster". Getty images. Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- ^ "The Centuries-Old Reason Why Queen Elizabeth Is Also Known as the Duke of Lancaster". Town an Country Magazine. 27 November 2018. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- ^ Sly, Nicola (2012). In Hot Blood: A Casebook of Historic British Crimes of Passion. The History Press. ISBN 978-0752492216.

- ^ "Lancastrian Organ Gems". Arkiv Music. Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- ^ "Antiques Roadshow". BBC. Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- ^ "Lancaster's former magistrates' court reopens as Nightingale Court during Covid-19 pandemic". Lancaster Guardian. Retrieved 21 August 2021.

- ^ "Jewel in Lancaster Crown Court history". Lancaster Guardian. Retrieved 21 August 2021.

- City and town halls in Lancashire

- Grade II* listed buildings in Lancashire

- Government buildings completed in 1909