Larry King

Larry King | |

|---|---|

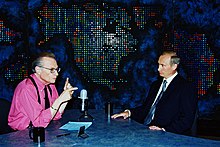

King in 2017 | |

| Born | Lawrence Harvey Zeiger[1] November 19, 1933 Brooklyn, New York, U.S. |

| Died | January 23, 2021 (aged 87) Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Occupation |

|

| Years active | 1957–2021 |

| Spouse(s) | Freda Miller

(m. 1952; ann. 1953)Annette Kaye

(m. 1961; div. 1961)Alene Akins

(m. 1961; div. 1963)

(m. 1967; div. 1972)Mickey Sutphin

(m. 1963; div. 1967)Sharon Lepore

(m. 1976; div. 1983)Julie Alexander

(m. 1989; div. 1992)Shawn Southwick

(m. 1997, sep;2019) |

| Children | 5 |

Larry King (born Lawrence Harvey Zeiger; November 19, 1933 – January 23, 2021)[2] was an American television and radio host, whose awards included two Peabodys, an Emmy and ten Cable ACE Awards.[3][4][5][6] Over his career, he hosted over 50,000 interviews.[7]

King was a WMBM radio interviewer in the Miami area in the 1950s and 1960s, and gained prominence in 1978 as host of The Larry King Show, an all-night nationwide call-in radio program heard on the Mutual Broadcasting System.[8] From 1985 to 2010, he hosted the nightly interview television program Larry King Live on CNN.[9][10] King hosted Larry King Now from 2012 to 2020,[11] which aired on Hulu, Ora TV, and RT America. He hosted Politicking with Larry King, a weekly political talk show, on the same three channels from 2013 to 2020. King also appeared in television series and films, usually playing himself.

Early life and education[]

King was born in Brooklyn, on November 19, 1933.[12] He was one of two children of Jennie (Gitlitz), a garment worker who was born in Minsk, Russian Empire, and Aaron Zeiger, a restaurant owner and defense-plant worker who was born in Pinsk, Russian Empire.[13][14][15] His parents were Orthodox Jews who immigrated to the United States from Belarus in the 1930s.[1][16][17]

King attended Lafayette High School, a public high school in Brooklyn.[18] King's father died of a heart attack when King was nine years old.[19][20] This resulted in King, his mother, and brother going on government welfare.[19] King was greatly affected by his father's death, and subsequently lost interest in his schoolwork.[21][22]

After graduating from high school, Larry worked to help support his mother.[23] From an early age, he desired to work in radio broadcasting.[23]

Career[]

Miami radio and television[]

A CBS staff announcer, whom King met by chance, suggested he go to Florida which was a growing media market with openings for inexperienced broadcasters. King went to Miami, and after initial setbacks, he gained his first job in radio. The manager of a small station, WAHR[24] (now WMBM)[25] in Miami Beach, hired him to clean up and perform miscellaneous tasks.[26] When one of the station's announcers abruptly quit, King was put on the air. His first broadcast was on May 1, 1957, working as the disc jockey from 9 a.m. to noon.[27] He also did two afternoon newscasts and a sportscast. He was paid $50 a week.

He acquired the name Larry King when the general manager claimed that Zeiger was too difficult to remember, so minutes before airtime, Larry chose the surname King, which he got from an advertisement in the Miami Herald for King's Wholesale Liquor.[28] Within two years, he legally changed his name to Larry King.[29]

He began to conduct interviews on a mid-morning show for WIOD, at Pumpernik's Restaurant in Miami Beach.[30] He would interview whoever walked in. His first interview was with a waiter at the restaurant.[31] Two days later, singer Bobby Darin, in Miami for a concert that evening, walked into Pumpernik's[32][33] having heard King's radio show; Darin became King's first celebrity interview guest.[34][35]

King's Miami radio show brought him local attention. A few years later, in May 1960, he hosted Miami Undercover, airing Sunday nights at 11:30 p.m. on WPST-TV Channel 10 (now WPLG).[36]

King credited his success on local television to the assistance of comedian Jackie Gleason, whose national television variety show was being taped in Miami Beach beginning in 1964. "That show really took off because Gleason came to Miami," King said in a 1996 interview he gave when inducted into the Broadcasters' Hall of Fame. "He did that show and stayed all night with me. We stayed till five in the morning. He didn't like the set, so we broke into the general manager's office and changed the set. Gleason changed the set, he changed the lighting, and he became like a mentor of mine."[37]

During this period, WIOD gave King further exposure as a color commentator for the Miami Dolphins of the National Football League, during their 1970 season and most of their 1971 season.[38] However, he was dismissed by both WIOD and television station WTVJ as a late-night radio host and sports commentator as of December 20, 1971, when he was arrested after being accused of grand larceny by a former business partner, Louis Wolfson.[39][40] Other staffers covered the Dolphins' games into their 24–3 loss to Dallas in Super Bowl VI. King also lost his weekly column at the Miami Beach Sun newspaper. The charges were dropped.[40][41] Eventually, King was rehired by WIOD.[40] For several years during the 1970s, he hosted a sports talk-show called "Sports-a-la-King" that featured guests and callers.[34]

The Larry King Show[]

On January 30, 1978, King began broadcasting a nightly coast-to-coast program on the Mutual Broadcasting System,[42] inheriting the talk show slot that had begun with Herb Jepko in 1975, then followed by "Long John" Nebel in 1977, until his illness and death the following year.[43] King's Mutual show rapidly developed a devoted audience,[44] called "King-aholics".[45]

The Larry King Show[42] was broadcast live Monday through Friday from midnight to 5:30 a.m. Eastern Time. King would interview a guest for the first hour, with callers asking questions that continued the interview for the next two hours.[45] At 3 a.m., the Open Phone America segment began, where he allowed callers to discuss any topic they pleased with him,[44][46] until the end of the program when he expressed his own political opinions. Many stations in the western time zones carried the Open Phone America portion of the show live, followed by the guest interview on tape delay.[47][25]

Some of King's regular callers used pseudonyms or were given nicknames by King, such as "The Numbers Guy",[48] "The Chair", "The Portland Laugher",[44] "The Miami Derelict", and "The Scandal Scooper".[49] At the beginning, the show had 28 affiliates,[50] though the number was eventually above 500. King hosted the show until stepping down in 1994.[51] King occasionally entertained the audience by telling amusing stories from his youth or early broadcasting career.[52][53][46][24]

For its final year, the show was moved to afternoons. After King stepped down, Mutual gave the afternoon slot to David Brenner[54] and Mutual's affiliates were given the option of carrying the audio of King's new CNN evening television program. After Westwood One dissolved Mutual in 1999, the radio simulcast of the CNN show continued until December 31, 2009.[55]

Larry King Live[]

Larry King Live began on CNN in June 1985. On the show, King hosted a broad range of guests, from figures such as UFO conspiracy theorists and alleged psychics,[56] to prominent politicians and entertainment industry figures, often doing their first or only interview on breaking news stories on his show. After broadcasting his CNN show from 9 to 10 p.m., King then traveled to the studios of the Mutual Broadcasting System to do his radio show,[57] when both shows still aired.

Two of his best-remembered interviews involved political figures. In 1992, billionaire Ross Perot announced his presidential bid on the show. In 1993, a debate between Al Gore and Perot became CNN's most-watched segment until 2015.[3]

Unlike many interviewers, King had a direct, non-confrontational approach. His reputation for asking easy, open-ended questions made him attractive to important figures who wanted to state their position while avoiding being challenged on contentious topics.[58] King said that when interviewing authors, he did not read their books in advance, so that he would not know more than his audience.[8][57] Throughout his career, King interviewed many of the leading figures of his time. According to CNN, King conducted more than 30,000 interviews in his career.[59]

King also wrote a regular newspaper column in USA Today for almost 20 years, from shortly after that first national newspaper's debut in Baltimore-Washington in 1982 until September 2001.[60] The column consisted of short "plugs, superlatives and dropped names" but was dropped when the newspaper redesigned its "Life" section.[61] The column was resurrected in blog form in November 2008[62] and on Twitter in April 2009.[63]

During his career, he did more than 60,000 interviews.[64] CNN's Larry King Live became "the longest-running television show hosted by the same person, on the same network and in the same time slot", and was recognized for it by the Guinness Book of World Records.[65] He retired in 2010 after taping 6,000 episodes of the show.[66]

Departure[]

On June 29, 2010, King announced that after 25 years, he would be stepping down as the show's host. However, he stated that he would remain with CNN to host occasional specials.[67] The announcement came in the wake of speculation that CNN had approached Piers Morgan, the British television personality and journalist, as King's primetime replacement,[68] which was confirmed that September.[69][70]

The final edition of Larry King Live aired on December 16, 2010.[71] The show concluded with his last thoughts and a thank you to his audience for watching and supporting him over the years. The concluding words of Larry King on the show were, "I... I, I don't know what to say except to you, my audience, thank you. And instead of goodbye, how about so long."[72]

On February 17, 2012, CNN announced that he would no longer host specials.[73]

Shows on Ora TV[]

In March 2012, King co-founded Ora TV, a production company, with Mexican business magnate Carlos Slim. On January 16, 2013, Ora TV celebrated their 100th episode of Larry King Now. In September 2017, King stated that he had no intention of ever retiring and expected to host his programs until he died.[74]

Ora TV signed a multi-year deal with Hulu to exclusively carry King's new talk-oriented web series, Larry King Now, beginning July 17.[75] On October 23, 2012, King hosted the third-party presidential debate on Ora TV, featuring Jill Stein, Rocky Anderson, Virgil Goode, and Gary Johnson.[76]

In May 2013, the Russian-owned RT America network announced that they struck a deal with Ora TV to host the Larry King Now show on its network. King said in an advertisement on RT America: "I would rather ask questions to people in positions of power, instead of speaking on their behalf." The show continued to be available on Hulu.com and Ora.tv.[77]

When criticized for doing business with a Russian-owned TV network in 2014, King responded, "I don't work for RT", commenting that his podcasts, Larry King Now and Politicking, are licensed for a fee to RT America by New York-based Ora TV. "It's a deal made between the companies ... They just license our shows. If they took something out, I would never do it. It would be bad if they tried to edit out things. I wouldn't put up with it."[78]

Other ventures[]

King remained active as a writer and television personality thereafter.

King guest starred in episodes of Arthur, 30 Rock and Gravity Falls, had cameos in Ghostbusters and Bee Movie, and voiced Doris the Ugly Stepsister in Shrek 2 and its sequels.[5] He also played himself in The People v. O. J. Simpson: American Crime Story[79][80] and appeared as himself in an episode of Law and Order: Trial by Jury.

King hosted the educational television series In View with Larry King from 2013 to 2015, which was carried on cable television networks including Fox Business Network and Discovery[81] and produced by The Profiles Series production company.[82]

King and his wife Shawn appeared on WWE Raw in October 2012, participating in a storyline involving professional wrestlers The Miz and Kofi Kingston.[83]

King became a very active user on the social-networking site Twitter, where he posted thoughts and commented on a wide variety of subjects. King stated, "I love tweeting, I think it's a different world we've entered. When people were calling in, they were calling into the show and now on Twitter, I'm giving out thoughts, opinions. The whole concept has changed."[84]

After 2011, he also made various television infomercials, often appearing as a "host" discussing products like Omega-3 fatty acid dietary supplement OmegaXL with guests, in an interview style reminiscent of his past television programs.[85][86][87]

ProPublica reported that in 2019 King had been manipulated into starring in a fake interview with a Russian journalist containing disinformation about Chinese dissident Guo Wengui, which was subsequently spread by Chinese government associated social media accounts.[88]

Charitable works[]

Following his 1987 heart attack, King founded the Larry King Cardiac Foundation, a non-profit organization[89][90] which paid for life-saving cardiac procedures for people who otherwise would not be able to afford them.[91]

On August 30, 2010, King served as the host of Chabad's 30th annual "To Life" telethon, in Los Angeles.[92]

He donated to the Beverly Hills 9/11 Memorial Garden, and his name is on the monument.[93]

Personal life[]

King was married eight times, to seven women.[94] He married high-school sweetheart Freda Miller in 1952 at age 19.[95] That union ended the following year at the behest of their parents, who reportedly had the marriage annulled.[95] He was later briefly married to Annette Kaye,[95] who gave birth to his son, Larry Jr., in November 1961. King did not meet Larry Jr. until the latter was in his thirties.[96]

In 1961, King married his third wife, Alene Akins, a Playboy Bunny, at one of the magazine's eponymous nightclubs. He adopted Akins' son Andy in 1962; the couple divorced the following year.[95] In 1963, he married his fourth wife, Mary Francis "Mickey" Sutphin, who divorced him.[95] He remarried Akins, with whom he had a second child, Chaia, in 1969.[95] The couple divorced a second time in 1972.[95] In 1997, Dove Books published a book written by King and Chaia, Daddy Day, Daughter Day. Aimed at young children, it tells each of their accounts of his divorce from Akins.

On September 25, 1976, King married his fifth wife, mathematics teacher and production assistant Sharon Lepore. The couple divorced in 1983.[97]

King met businesswoman Julie Alexander in 1989, and proposed to her on the couple's first date on August 1, 1989.[98] Alexander became King's sixth wife on October 7, 1989, when the two were married in Washington, D.C.[99] The couple lived in different cities, however, with Alexander in Philadelphia, and King in Washington, D.C., where he worked. They separated in 1990 and divorced in 1992.[99] He became engaged to actress Deanna Lund in 1995, after five weeks of dating, but they remained unmarried.[100]

In 1997, he married his seventh wife, Shawn Southwick, born in 1959[101][102] (as Shawn Ora Engemann),[101] a singer, actress, and TV host.[103] They wed in King's Los Angeles hospital room three days before he underwent heart surgery to clear an occluded blood vessel.[102] The couple had two children: Chance, born March 1999, and Cannon, born May 2000.[104] He was stepfather to Arena Football League quarterback Danny Southwick.[105] On King and Southwick's 10th anniversary in September 2007, Southwick joked she was "the only [wife] to have lasted into the two digits".[103] Larry and Shawn King filed for divorce in 2010 but reconciled,[102][106][107] and filed for divorce again on August 20, 2019.[108][109]

From his seven wives, King had five children and nine grandchildren, as well as four great-grandchildren.[110][111] His children with Alene (Andy and Chaia), died within weeks of each other in August 2020, Andy at 65 from a heart attack and Chaia at 51 from lung cancer.[111][112]

King resided in Beverly Hills, California.[113] A lifelong Brooklyn Dodgers/Los Angeles Dodgers fan, he was frequently seen behind home plate at the team's games.[114] He was previously part of an investment group that attempted to bring a Major League Baseball franchise to Buffalo, New York, in 1990.[115] He lost $2.8 million to Bernie Madoff.[41]

After describing himself as a Jewish agnostic in 2005,[116] King stated that he was fully atheist in 2015.[117] In 2009,[41] 2011,[118] and several times in 2015,[117][119] King stated that he would like to undergo cryonic suspension subsequent to his legal death. In 2017, he stated "I love being Jewish, am proud of my Jewishness, and I love Israel".[120]

Illnesses and death[]

On February 24, 1987, King had a major heart attack before a successful quintuple-bypass surgery.[53][121] Following this, he wrote two books about living with heart disease. Mr. King, You're Having a Heart Attack: How a Heart Attack and Bypass Surgery Changed My Life (1989, ISBN 978-0-440-50039-1) that was written with New York's Newsday science editor B. D. Colen and Taking On Heart Disease: Famous Personalities Recall How They Triumphed over the Nation's #1 Killer and How You Can, Too (2004, ISBN 978-1-57954-820-9) which features the experience of various celebrities with cardiovascular disease including Peggy Fleming and Regis Philbin.[122]

King related his heart attack experience in an interview in the 2014 British documentary film The Widowmaker, which advocates for coronary calcium scanning to motivate preventive cardiology and highlights the financial conflicts of interest in the widespread use of coronary stents.[123][124][125] He received annual chest X-rays to monitor his heart condition. During his 2017 examination, doctors discovered a cancerous tumor in his lung. It was then successfully removed with surgery.[74]

On April 23, 2019, King underwent a scheduled angioplasty and also had stents inserted. It was erroneously reported that he had another heart attack along with heart failure; these claims were later retracted.[126] He returned to Politicking with Larry King on August 15. On November 27, he said he had had a stroke in March, and was in a coma "for weeks".[127] He later admitted he had contemplated suicide following the stroke, telling Los Angeles television station KTLA, "I thought I was just going to bite the bullet. I didn't want to live this way."[128]

On January 2, 2021, it was revealed that King had been hospitalized ten days earlier in a Los Angeles hospital after testing positive for COVID-19.[129] King died on January 23, 2021 at the age of 87 at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles.[2][3][5][130] King's wife Shawn told Entertainment Tonight that he had recovered from COVID-19, but he died of sepsis as a complication.[131][132] The death certificate obtained by the magazine People also listed sepsis as the immediate cause of death, while also listing two underlying conditions leading to the infection - acute hypoxemic respiratory failure and end-stage renal disease.[133]

In February 2021, it was reported that King's widow Shawn Southwick-King had gone to court to contest the deceased's handwritten will written in 2019, which had left his estate (valued at $2 million) to his five surviving children. Shawn alleges her stepson Larry King Jr. exerted undue influence over his father towards the end of his life, and that the handwritten will conflicts with a will he signed in 2015, in which she was named executor of his estate.[134] This does not include more valuable "assets that were held in trusts".[135]

Filmography[]

Film[]

| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1984 | Ghostbusters | Larry King | [22] |

| 1985 | Lost in America | Voice[136] | |

| 1989 | Eddie and the Cruisers II: Eddie Lives! | Talk show host | |

| 1990 | Crazy People | Larry King | |

| 1990 | The Exorcist III | ||

| 1993 | Dave | ||

| 1993 | We're Back! A Dinosaur's Story | Voice | |

| 1995 | |||

| 1996 | The Long Kiss Goodnight | Larry King | |

| 1997 | Contact | [22] | |

| 1997 | The Jackal | ||

| 1998 | Primary Colors | ||

| 1998 | Bulworth | ||

| 1998 | Enemy of the State | ||

| 2000 | The Contender | ||

| 2000 | The Kid | [22] | |

| 2002 | John Q | ||

| 2004 | The Stepford Wives | ||

| 2004 | Shrek 2 | Doris | Voice (U.S. Version) |

| 2007 | Shrek the Third | Voice | |

| 2007 | Bee Movie | Bee Larry King | Voice[41] |

| 2008 | Swing Vote | Larry King | |

| 2010 | Shrek Forever After | Doris | Voice |

| 2012 | The Dictator | Larry King | |

| 2013 | The Power of Few | ||

| 2015 | Chloe & Theo | ||

| 2017 | American Satan | Final film role |

Television[]

| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1961 | Miami Undercover | Sleepy Sam | Episode: The Thrush |

| 1985-2010 | Larry King Live | Self; Host | 6,076 Episodes |

| 1990-96 | Murphy Brown | Larry King | 2 episodes |

| 1991-92 | The Simpsons | Voice; 2 episodes | |

| 1995 | The Larry Sanders Show | Episode: The P.A. | |

| 1995 | Coach | Episode: Is it Hot in Here or is it Just Me? | |

| 1996 | Murder One | Episode: Chapter Twenty-One | |

| 1996 | Bonnie | Episode: Better Offer | |

| 1997 | Spin City | Episode: An Affair to Remember | |

| 1997 | Frasier | Episode: My Fair Frasier | |

| 2002 | The Practice | Episode: The Verdict | |

| Arli$$ | Episode: Standards and Practice | ||

| Arthur | Episode: Elwood City Turns 100! | ||

| 2004 | Sesame Street | Episode: 4074 | |

| 2005 | Boston Legal | Episode: Truly, Madly, Deeply | |

| Law and Order: Trial by Jury | Episode: Day | ||

| 2006 | Law and Order: Criminal Intent | Episode: Weeping Willow | |

| 2007 | Shark | Episode: Wayne's World 2: Revenge of the Shark | |

| The Closer | Episode: Til Death do Us Part - Part II | ||

| 2008 | Ugly Betty | Episode: The Kids are all right | |

| 2009 | 30 Rock | Episode: Larry King[41] | |

| 2012-16 | Gravity Falls | Wax Larry King | 2 episodes |

| 2013 | 1600 Penn | Larry King | Episode: Marry Me, Baby |

| 2014 | Murder in the First | Episode: Family Matters | |

| 2016 | The People v. O.J. Simpson | 4 episodes |

Awards and nominations[]

King received many broadcasting awards. He won the Peabody Award for Excellence in broadcasting for both his radio (1982)[3][137] and television (1992)[138][137] shows. He also won ten CableACE awards for Best Interviewer and for Best Talk Show Series.[3]

In 1989, King was inducted into the National Radio Hall of Fame,[139] and in 1996 to the Broadcasters' Hall of Fame.[23] In 2002, the industry publication Talkers Magazine named King both the fourth-greatest radio talk show host of all time and the top television talk show host of all time.[140]

In 1994, King received the Scopus Award from the American Friends of Hebrew University.[1][141] In 1996, he received the Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement presented by Awards Council member Art Buchwald.[142]

He was given the Golden Mike Award for Lifetime Achievement in January 2008, by the Radio & Television News Association of Southern California.[3]

King was an honorary member of the Rotary Club of Beverly Hills.[143] He was also a recipient of the President's Award honoring his impact on media from the Los Angeles Press Club in 2006.[144]

King was the first recipient of the Arizona State University Hugh Downs Award for Communication Excellence,[145] presented April 11, 2007, via satellite by Downs himself.[146]

King was awarded an honorary degree of Doctor of Humane Letters by Bradley University; for which he said "is really a hoot". King received numerous honorary degrees from George Washington University, the Columbia School of Medicine, Brooklyn College, the New England Institute of Technology, and the Pratt Institute.[147][148]

In 2003, King was named as recipient of the Snuffed Candle Award by the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry's Council for Media Integrity. King received this award for '"encouraging credulity (and) presenting pseudoscience as genuine'".[149][150]

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Larry King". Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved September 6, 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b King, Larry [@kingsthings] (January 23, 2021). "Larry King 1933 – 2021 ..." (Tweet). Retrieved January 23, 2021 – via Twitter.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Miller, Hayley; Moran, Lee (January 23, 2021). "Larry King, Iconic TV And Radio Interviewer, Dies At 87". HuffPost – via Yahoo!.

He rose above personal tragedy, financial despair and half a dozen divorces to become one of the most revered and prolific interviewers in broadcasting.

- ^ Dalton, Andrew; Moore, Frazier. "Larry King, broadcasting giant for half-century, dies at 87 January 23, 2021". Pittsburg Post-Gazette. Associated Press.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Reed, Ryan; Kreps, Daniel (January 23, 2021). "Larry King, Veteran TV and Radio Host, Dead at 87". Rolling Stone.

- ^ Spangler, Todd (July 28, 2013). "Larry King Politics Show Gets Global TV Distribution via Russian-Backed Network". Variety. Penske Media Corporation. Retrieved September 27, 2015.

- ^ "Larry King: US TV legend who hosted 50,000 interviews". BBC News. January 23, 2021. Retrieved January 25, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Larry King Mutual Radio 1982". YouTube. Retrieved November 2, 2015.

- ^ "Larry King Live". Retrieved January 26, 2021.

- ^ "End Of Qtr Data-Q107 (minus 3 hours).xls" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 24, 2009. Retrieved October 21, 2010.

- ^ "Larry King Now". Ora TV. Retrieved January 26, 2021.

- ^ "Five interesting things about Larry King". Associated Press. Associated Press. November 19, 2018. Archived from the original on January 3, 2021. Retrieved January 3, 2021.

- ^ Bloom, Nate (April 18, 2008). "Celebrities". Jewish Weekly. Archived from the original on March 18, 2014. Retrieved October 12, 2015.

- ^ Wenig, Gaby (November 14, 2003). "Q & A With Larry King". Jewish Journal. Archived from the original on March 24, 2004. Retrieved February 15, 2008.

- ^ King, Larry; Appel, Martin (1993). When You're from Brooklyn, Everything Else is Tokyo. Thorndike Press. ISBN 978-1-56054-661-0.

- ^ Obituaries, Telegraph (January 23, 2021). "Larry King, broadcaster whose CNN show was the platform of choice for politicians and celebrities – obituary". The Daily Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- ^ "Легендарный американский телеведущий 76-летний Ларри Кинг разводится в восьмой раз". bulvar.com.ua. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- ^ Gay, Jason (March 7, 2013). "Larry King: Back in Brooklyn". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on January 3, 2021. Retrieved March 8, 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Larry King: 'The secret of my success? I'm dumb'". The Guardian. November 5, 2015.

- ^ Leibovich, Mark (August 26, 2015). "Larry King Is Preparing for the Final Cancellation (Published 2015)". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 25, 2021.

- ^ McFadden, Robert D. (January 23, 2021). "Larry King, Breezy Interviewer of the Famous and Infamous, Dies at 87". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Parker, Vernon (November 19, 2010). "King of the Brooklyn Celebrity Path". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Archived from the original on November 19, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Larry King biography". Achievement.org. Broadcaster's Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on February 1, 1998. Retrieved July 27, 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b King, Larry (2001). Larry King on Getting Seduced. Blank on Blank. Interviewed by Cal Fussman. Los Angeles: PBS Digital Studios. Archived from the original on January 3, 2021. Transcript. Retrieved July 23, 2014 – via YouTube.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Wagoner, Richard (January 25, 2021). "Remembering Larry King and the success of his nationwide radio show – Daily News". Dailynews.com. Retrieved February 12, 2021.

- ^ "Larry King Biography". WhyFame. Archived from the original on April 10, 2010. Retrieved February 18, 2012.

- ^ Johnson, Caitlin A. (February 11, 2009). "Larry King Celebrates 50 Years On Air". CBS News. Retrieved February 18, 2012.

- ^ Christina and Jordana (July 5, 2010). "Goodbye Larry King". Schema Magazine. Archived from the original on July 16, 2010. Retrieved February 18, 2012.

- ^ "The Nine Lives Of Larry King". Sun Sentinel. Archived from the original on October 18, 2015. Retrieved November 2, 2015.

- ^ Pekkanen, John (March 10, 1980). "While Most of America Sleeps, Larry King Talks to Six Million People All Through the Night". People. Archived from the original on March 17, 2016. Retrieved February 18, 2012.

- ^ "Legendary Talk Show Host Larry King Joins the Original Brooklyn Water Bagel Co". Brooklyn Water Bagel Co. Archived from the original on December 14, 2011. Retrieved February 18, 2012.

- ^ Sargalski, Trina (November 22, 2013). "Key Facts Of Miami's Delis Of Yore, From Deli Historian Ted Merwin". wlrn.org. Archived from the original on January 3, 2021. Retrieved July 25, 2017.

- ^ "Pumperniks - Restaurant-ing through history". restaurant-ingthroughhistory.com. Archived from the original on January 3, 2021. Retrieved July 25, 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Brounstein, Diane (January 23, 2021). "Larry King, A Beloved Talk Show Icon, Has Passed Away At Age 87". soaphub.com.

- ^ King, Larry (May 5, 2009). "Excerpt: How I Became Larry King". CNN. Archived from the original on March 26, 2012. Retrieved February 18, 2012.

- ^ Bershad, Jon (June 30, 2010). "From the Mediaite Vault: Larry King Takes on Gangsters (and Loses) in 1961". Mediaite (blog). Retrieved February 18, 2012.

- ^ "The Interview King". Academy of Achievement. June 29, 1996. Archived from the original on February 1, 1998. Retrieved March 3, 2008.

- ^ "Larry King – Talk Show Host". dLife. Archived from the original on December 17, 2011. Retrieved February 18, 2012.

- ^ "Larry King". The Smoking Gun. July 13, 2010. Retrieved February 18, 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "The Nine Lives Of Larry King". Sun Sentinel. Archived from the original on June 30, 2015. Retrieved November 2, 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Heath, Chris (May 1, 2009). "The Enduring Larry King". GQ. Retrieved February 1, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Listen! You're going to hear things you've never heard before". dcrtv.com Photo Gallery. Archived from the original on April 2, 2018. Retrieved November 20, 2014. Alt URL

- ^ "Mutual Broadcasting System". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Midnight Snoozer". Harvard Crimson. Retrieved November 2, 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Davies, Tom (January 4, 1981). "The Radio 'King': From Midnight to Dawn". Toledo Blade. Retrieved November 28, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Spade, Doug; Clement, Mike (January 29, 2021). "Farewell to the King - Opinion - The Daily Reporter - Coldwater, MI". The Daily Reporter. Retrieved January 30, 2021.

- ^ "Listeners pay close attention to late-night radio broadcast". The Gettysburg Times. March 22, 1982. p. 13. Archived from the original on October 18, 2015. Retrieved November 2, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Technical Correction / "The Numbers Guy" And Wall Street". San Francisco Chronicle. November 21, 2000.

- ^ King, Larry; Yoffe, Emily (1984). Larry King. Berkley Books. ISBN 978-0-425-06831-1. Retrieved July 25, 2017 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Larry King, TV broadcaster and talk-show host, dies at 87". Los Angeles Times. January 23, 2021.

- ^ "Larry King Bio". Archived from the original on May 14, 2009.

- ^ King, Larry (2010). My Remarkable Journey. ISBN 978-1-60286-123-7. Retrieved November 2, 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "The Nine Lives Of Larry King". Sun Sentinel. Archived from the original on November 29, 2014. Retrieved November 2, 2015.

- ^ "Today's Talk-Radio Topic: The Future of Talk Radio". Los Angeles Times. June 24, 1994. Archived from the original on October 18, 2015. Retrieved November 2, 2015.

- ^ "Westwood One Ends Larry King Show Simulcast". Radio Syndication Talk. Retrieved November 2, 2015.

- ^ One notable guest is Sylvia Browne, who in 2005 told the Newsweek magazine that King, a believer in the paranormal, asks her to do private psychic readings. Setoodeh, Ramin (January 14, 2005). "Predictions: Jacko Convicted, But Blake Gets Off". Newsweek. Archived from the original on February 11, 2007. Retrieved January 31, 2007.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "The Man Who Can't Stop Talking Starting In South Florida, Larry King Has Been Live And On The Air For More Than 30 Years. On Radio And Tv, When The King Of Talk Speaks, The World Listens". Sun Sentinel. Archived from the original on June 30, 2015. Retrieved November 2, 2015.

- ^ Barry, Ellen (December 1, 2010). "Blunt and Blustery, Putin Responds to State Department Cables on Russia". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 3, 2021. Retrieved December 3, 2010.

- ^ Larry King Fast Facts CNN. May 5, 2013

- ^ King, Larry (September 23, 2001). "A New York boy pays tribute, bids farewell". USA Today. Archived from the original on September 6, 2011. Retrieved October 19, 2009.

- ^ Barringer, Felicity (September 5, 2001). "Larry King's Weekly Column for USA Today to Be Dropped". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 3, 2021. Retrieved October 19, 2009.

- ^ King, Larry (November 24, 2008). "King's Things: It's My Two Cents". CNN. Retrieved October 19, 2009.

- ^ King, Larry. "King's Things". Twitter. Archived from the original on March 3, 2011. Retrieved October 19, 2009.

- ^ Levin, Gary (January 23, 2021). "Larry King, CNN talk-show legend, dies at 87 after being hospitalized with COVID-19". USA Today – via The Columbus Dispatch.

By his count, he interviewed well over 60,000 subjects, and when his run on cable ended in 2010, he segued to the Internet with "Larry King Now," a daily talk show on Hulu from Ora TV, and became an active presence on Twitter. ... King’s interview subjects were a virtual Who’s Who. They ranged from the late Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat and the late Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin, U.S. presidents Bill Clinton and George W. Bush, and thousands of others, including Paul McCartney, Bette Davis, Dr. Martin Luther King, Eleanor Roosevelt, Frank Sinatra, Marlon Brando, Madonna and Malcolm X.

- ^ Martinez, Michael (December 17, 2010). "Larry King ends his record-setting run on CNN". CNN. Retrieved January 24, 2021.

- ^ Kludt, Tom; Parks, Brad; Sanchez, Ray (January 24, 2021). "Larry King, legendary talk show host, dies at 87". CNN.

- ^ "Larry King to end long-running US TV chat show". BBC News. BBC. June 30, 2010. Retrieved September 9, 2010.

- ^ "CNN denies Larry King will be replaced". . Media Spy. June 16, 2010. Archived from the original on November 18, 2010. Retrieved September 9, 2010.

- ^ "Piers Morgan signs on as Larry King replacement". The Spy Report. Media Spy. September 9, 2010. Archived from the original on September 15, 2010. Retrieved September 9, 2010.

- ^ Duke, Alan; Braiker, Brian (June 30, 2010). "Piers Morgan to join CNN with prime-time hour in Larry King slot". ABC News. ABC. Retrieved September 9, 2010.

- ^ "Larry King signs off from CNN talk show". The Spy Report. Media Spy. December 17, 2010. Archived from the original on December 23, 2010. Retrieved December 17, 2010.

- ^ "Photos: Larry King's Final CNN "Larry King Live" Broadcast Party". iknowjack.radio.com. Archived from the original on December 22, 2010.

- ^ "CNN officially severs ties with Larry King". Los Angeles Times. February 15, 2012. Retrieved February 18, 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Burroni, Christine (September 13, 2017). "Larry King reveals lung cancer diagnosis". The New York Post. Archived from the original on January 16, 2021. Retrieved September 13, 2017.

- ^ Wallenstein, Andrew (July 17, 2012). "Larry King's 'Now' to stream on Hulu: Internet vid giant pacts with Carlos Slim Helu's Ora TV venture". Chicago Tribune. Variety. Archived from the original on July 18, 2012. Retrieved July 17, 2012.

- ^ "Third-party candidates face off in US debate". Al Jazeera English. October 23, 2012.

- ^ Dylan Byers, Larry King joins Russian channel RT, Politico, May 29, 2013.

- ^ Larry King's Russian TV Dilemma The Daily Beast March 6, 2014.

- ^ "Superfan: Larry King Lost His Mind While Shooting 'The People v. O.J.' With Connie Britton". March 10, 2016. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- ^ Robinson, Will (March 21, 2016). "Marcia Clark: People v OJ Simpson is so accurate, it's painful to watch". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- ^ "Larry King's IN VIEW Television Show to Feature Help Hospitalized Veterans" Retrieved November 2015.

- ^ Greater Baton Rouge Business Report Retrieved November 2015.

- ^ ""Larry King NOW" with The Miz and Kofi Kingston: photos". WWE.

- ^ "Larry King on his dream guest, Twitter, and the 100th episode of 'Larry King Now'". EW.com.

- ^ "Larry King Returns to TV – as BreathGemz Pitchman | News". AdAge. April 6, 2011. Archived from the original on October 16, 2016. Retrieved March 11, 2017.

- ^ Dalton, Andrew (January 23, 2021). "Larry King, broadcasting giant for half-century, dies at 87". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- ^ Mushnick, Phil (October 12, 2013). "Don't trust those celeb endorsements". New York Post. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- ^ Dudley, Renee; Kao, Jeff (July 30, 2020). "The Disinfomercial: How Larry King Got Duped Into Starring in Chinese Propaganda". ProPublica. Retrieved August 17, 2020.

- ^ Dakin Andone and Brad Parks. "Larry King has been hospitalized with Covid-19". CNN. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- ^ "What was Larry King's net worth?". Fox Business. January 23, 2021.

Broadcast legend had lucrative career, supported philanthropic causes.

- ^ "Life Extension Magazine – Larry King Saves Lives". LifeExtension.com. Archived from the original on January 3, 2021. Retrieved December 31, 2017.

- ^ "Larry King to Host Chabad Telethon". August 29, 2010. Archived from the original on January 3, 2021. Retrieved August 25, 2016.

- ^ "Beverly Hills 9/11 Memorial Garden website: Donors". Archived from the original on March 3, 2016.

- ^ Starr, Michael (May 21, 2009). "Larry King Introduces the World to his Son Larry King Jr". New York Post. Retrieved June 6, 2009.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g "Larry King divorces Shawn Southwick: Meet the TV icon's slew of ex-wives". Daily News. April 16, 2010. p. 4 of 25.

- ^ "Transcript: Anderson Cooper 360 Degrees". CNN. May 21, 2009. Retrieved June 6, 2009.

- ^ Daily News, slide show. Daily News. pp. 5–6.

- ^ Cedar Rapids Gazette, August 23, 1989.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Daily News, slide show. Daily News. pp. 7–8.

- ^ Daily News, slide show. Daily News. p. 10.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Daily News, slide show, ibid., p. 11 of 25

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "CNN Host Larry King, 7th Wife File for Divorce". Associated Press (via The New York Times). April 14, 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Rush & Molloy (June 30, 2008). "The skinny on Larry King's wife". Daily News. Retrieved July 27, 2010.

- ^ "About.com - Marriage - The Marriages of Larry King". About. Archived from the original on January 3, 2021. Retrieved November 2, 2015.

- ^ "The Cable Hall of Fame Past Honorees". cablecenter.org. Archived from the original on May 20, 2013. Retrieved September 6, 2015.

- ^ Lee, Ken (April 14, 2010). "Larry King Files for Divorce – Breakups, Larry King". People. Retrieved July 27, 2010.

- ^ "Larry King and wife Shawn Southwick call off their divorce". NY Daily News. Archived from the original on January 3, 2021. Retrieved March 11, 2017.

- ^ "Larry King seeks divorce from seventh wife after 22 years". Associated Press. August 20, 2019. Archived from the original on January 3, 2021.

- ^ "Court Documents" (PDF). ExtraTV. August 20, 2019. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 3, 2021.

- ^ Crowley, James (January 23, 2021). "CULTURE:Who Are Larry King's 7 Ex-Wives? Shawn Southwick, Alene Akins, Annette Kaye". Newsweek.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Yasharoff, Hannah (August 23, 2020). "Celebrities: Larry King speaks out after his children Andy and Chaia die within weeks of each other". USA Today.

- ^ Yasharoff, Hannah. "Larry King speaks out after his children Andy and Chaia die within weeks of each other". USA TODAY. Archived from the original on January 3, 2021. Retrieved August 23, 2020.

- ^ King, Larry (June 1, 2016). "Larry King on His Path From Brooklyn to Beverly Hills". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on January 3, 2021. Retrieved August 29, 2016.

Today, my wife, Shawn, and I and our two boys live in Beverly Hills, in a two-story, five-bedroom house.

- ^ Gurnick, Ken (February 26, 2014). "Larry King to host show on SportsNet LA". MLB.com. Archived from the original on January 3, 2021. Retrieved November 2, 2017.

- ^ "Summer ends at pilot field; rich's investor group buoys big league quest". The Buffalo News. September 6, 1990. Archived from the original on January 3, 2021. Retrieved January 3, 2021.

- ^ "I don't know if there's a God. I'm a classic agnostic, but I'm a Jewish agnostic." Pogrebin, Abigail (2005). Stars of David: Prominent Jews Talk About Being Jewish. New York: Broadway. pp. 318–322. ISBN 978-0-7679-1612-7.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Gillespie, Nick (April 4, 2015). "Larry King Loves Cryonics & Rand Paul (!): 'I Want to Be Around to Pick Up the Pieces.'". Reason.com. Archived from the original on January 3, 2021. Retrieved August 24, 2020.

Reason: Are you still into cryonics? King: Yes. I'm putting it in my will. I'll tell you why. I'm an atheist. Most libertarians should be atheists.

- ^ "Larry King: I want to be frozen". CNN. December 2, 2011. Archived from the original on January 3, 2021. Retrieved December 3, 2011.

- ^ Gariano, Francesca (January 23, 2021). "Larry King was open about his wish 'to be frozen' after his death". The Today Show. Retrieved August 5, 2021.

- ^ Beeri, Tamar (January 23, 2021). "Larry King, legendary Jewish-American talk show host, dies at 87". The Jerusalem Post.

- ^ "Heart Health: Conquering the #1 Killer with Larry King". MedicineNet. February 24, 1987. Archived from the original on January 3, 2021. Retrieved January 18, 2014.

- ^ "Home Page". January 13, 2012. Archived from the original on January 13, 2012. Retrieved July 25, 2017.

- ^ Lenzer, Jeanne (2015). "Does a popular documentary about a "life saving" heart scan promote overtreatment?". BMJ. 351 (8029): h4926. doi:10.1136/bmj.h4926. Retrieved August 8, 2021.

- ^ O'Malley, Sheila. "The Widowmaker movie review & film summary (2015)". Roger Ebert. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- ^ Linden, Sheri (February 26, 2015). "MOVIES: Review: 'The Widowmaker' says doctors thrive on crisis over health". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- ^ "Larry King hospitalized for serious chest pain, did not suffer heart attack (updated)". AOL. April 29, 2019. Archived from the original on January 3, 2021. Retrieved August 21, 2019.

- ^ Concha, Joe. "Larry King says he had a stroke in March and was in coma: 'It's been a rough year'". thehill.com. Capitol Hill Publishing Corp., a subsidiary of News Communications, Inc. Archived from the original on January 3, 2021. Retrieved November 29, 2019.

- ^ Buckley, Frank. "Larry King Reveals He Considered Ending His Life After Health Complications". KTLA. Nexstar Media Group. Archived from the original on January 3, 2021. Retrieved January 18, 2020.

- ^ "Larry King Is Hospitalized With Coronavirus". NBC Bay Area. Archived from the original on January 3, 2021. Retrieved January 2, 2021.

- ^ Kludt, Tom; Parks, Brad Parks. "Larry King, legendary talk show host, dies at 87". CNN. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- ^ Bueno, Antoinette (January 27, 2021). "Shawn King Reveals Husband Larry King's Final Words to Her, Says COVID-19 Was Not Cause of Death". Entertainment Tonight. Retrieved January 28, 2021.

- ^ "Larry King (1933-2021) Obituary". We Remember. January 23, 2021.

- ^ Ushe, Naledi (February 12, 2021). "Larry King's Immediate Cause of Death and Underlying Conditions Revealed in Death Certificate". People. Retrieved July 6, 2021.

- ^ "Larry King: Talk show host's widow contests handwritten will". February 17, 2021 – via www.bbc.com.

- ^ Malito, Alessandra. "Larry King had a secret will that excluded his wife — estate planning gets messy". MarketWatch.

- ^ "Oprah Winfrey, Bill Clinton praise and mourn Larry King". ABC News.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "The Peabody Awards - The Larry King Show". www.peabodyawards.com. 1982. Archived from the original on January 3, 2021. Retrieved November 11, 2014.

- ^ "Larry King Live Election Coverage 1992". www.peabodyawards.com. Archived from the original on January 3, 2021. Retrieved November 11, 2014.

- ^ "Larry King". Radio Hall Of Fame. Retrieved January 24, 2021.

- ^ "The 25 Greatest Radio and Television Talk Show Hosts of All Time". Talkers Magazine. September 2002. Archived from the original on October 16, 2018. Retrieved February 15, 2008.

- ^ Byrne, Bridget (January 31, 1994). "King Crowned With Scopus Award". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on January 3, 2021. Retrieved August 29, 2016.

- ^ "Golden Plate Awardees of the American Academy of Achievement". www.achievement.org. American Academy of Achievement. Archived from the original on December 15, 2016. Retrieved December 8, 2020.

- ^ Eric (April 2020). "Larry King – Net Worth, Career, Awards and Nominations, Charitable Work And Personal Life". Gazette.

- ^ Johnson, Ted (2006). "Larry King - "Why, Who, What"" (PDF). www.lapressclub.org. Los Angeles Press Club. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- ^ "Hugh Downs honors Larry King with award for communication excellence". Time. April 3, 2007. Archived from the original on March 6, 2008. Retrieved February 15, 2008.

- ^ "Hugh Downs". Arizona State University: College of Liberal Arts and Sciences. 2008. Archived from the original (– Scholar search) on September 3, 2006.

- ^ "Larry King gives commencement keynote". lydia.bradley.edu. Bradley University. Retrieved June 2, 2016.

- ^ "CNN Programs - Anchors/Reporters - Larry King". CNN. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- ^ Nisbet, Matt (1999). "Candle in the Dark and Snuffed Candle Awards". Skeptical Inquirer. 23 (2): 6.

- ^ Frazier, Kendrick (2004). "From Internet Scams to Urban Legends, Planet (hoa)X to the Bible Code: CSICOP Albuquerque Conference Has Fun Exposing Hoaxes, Myths and Manias". Skeptical Inquirer. 28 (2): 7.

External links[]

- Larry King Live – Transcripts of all interviews since 2000

- Larry King at IMDb

- Larry King at The Interviews: An Oral History of Television

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- 1933 births

- 2021 deaths

- 20th-century American male writers

- 21st-century American male writers

- American atheists

- American columnists

- American newspaper writers

- American people of Austrian-Jewish descent

- American people of Belarusian-Jewish descent

- American people of Lithuanian-Jewish descent

- American people of Russian-Jewish descent

- American talk radio hosts

- American television talk show hosts

- Baseball spectators

- Cryonicists

- CNN people

- Deaths from sepsis

- Jewish American journalists

- Jewish American writers

- Jewish atheists

- Lafayette High School (New York City) alumni

- Male actors from Miami

- Male actors from New York City

- Miami Dolphins announcers

- National Football League announcers

- Peabody Award winners

- People from Beverly Hills, California

- People from Hollywood, Florida

- People from Miami Beach, Florida

- Radio personalities from Miami

- RT (TV network) people

- Writers from Brooklyn

- Writers from Florida