Laves graph

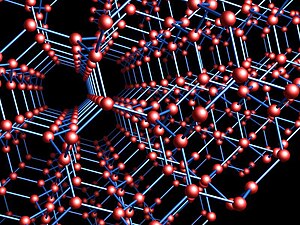

In geometry and crystallography, the Laves graph is an infinite periodic graph. Its vertices and edges consist of points and line segments in three-dimensional Euclidean space, with integer coordinates for the points.[1] As a graph, it is cubic, meaning that exactly three edges touch each vertex, and a symmetric graph, meaning that every arc (oriented edge) can be taken to every other arc by a symmetry of the graph. As a three-dimensional geometric structure, it has chiral symmetry.[1] The same graph can also be defined more abstractly as a covering graph of the complete graph on four vertices.[1][2]

H. S. M. Coxeter (1955) named this graph after Fritz Laves, who first wrote about it as a crystal structure in 1932.[3][4] It has also been called the K4 crystal,[5] (10,3)-a network,[6][7] diamond twin,[8] triamond,[9][10] and the srs net.[11]

Constructions[]

From the integer grid[]

As Coxeter (1955) describes, the vertices of the Laves graph can be defined by selecting one out of every eight points in the three-dimensional integer lattice, and forming their nearest neighbor graph. Specifically, one chooses the points

and all the other points that can be formed by adding multiples of four to these coordinates. The edges of the Laves graph connect pairs of points whose Euclidean distance from each other is the square root of two, (these pairs differ by one unit in two coordinates, and are the same in the third coordinate). The other non-adjacent pairs of vertices are farther apart, at a distance of at least from each other. The edges of the resulting geometric graph are diagonals of a subset of the faces of the regular skew polyhedron with six square faces per vertex, so the Laves graph is embedded in this skew polyhedron.[3]

It is possible to interleave two copies of the structure, filling one-fourth of the points of the integer lattice, while preserving the fact that the adjacent vertices are exactly the pairs of points that are units apart, and all other pairs of points are farther apart. The two copies are mirror images of each other.[6][11]

As a covering graph[]

As an abstract graph, the Laves graph can be constructed as the maximal abelian covering graph of the complete graph . Being a covering graph of means that there is a mathematical subgroup of symmetries of the Laves graph such that, when vertices that are symmetric to each other in this subgroup are collected together into orbits of the subgroup, there are four orbits, and each pair of orbits is connected by edges of the graph to each other one. More intuitively, this means that the vertices of the Laves graph can be colored with four colors so that each vertex has neighbors of the other three colors and so that there are color-preserving symmetries taking any vertex to any other vertex with the same color. Being an abelian covering graph means that these symmetries commute with each other, forming an abelian group. In this case, it is the group formed by addition of three-dimensional integer vectors. Finally, being a maximal abelian covering graph means that there is no other covering graph of involving a higher-dimensional abelian group. This construction justifies one of the alternative names of the Laves graph, the crystal.[1]

One way to construct a maximal abelian covering graph from a smaller graph (in this case ) is to choose a spanning tree of , let be the number of edges that are not in the spanning tree (in this case, three non-tree edges), and to choose a distinct unit vector in for each of these non-tree edges. Then, fix the set of vertices of the covering graph to be the ordered pairs where is a vertex of and is a vector in . For each such pair, and each edge adjacent to in , make an edge from to where is zero if belongs to the spanning tree and is otherwise the basis vector associated with , and where the plus or minus sign is chosen according to the direction the edge is traversed. The resulting graph is independent of the choice of the spanning tree, and the same construction can also be interpreted more abstractly using the theory of homology.[2]

Using the same construction, the hexagonal tiling of the plane is the maximal abelian covering graph of the three-edge dipole graph, and the diamond cubic is the maximal abelian covering graph of the four-edge dipole. The -dimensional integer lattice (with unit length edges) is the maximal abelian covering graph of a graph with one vertex and self-loops.[1]

Properties[]

The Laves graph is a cubic graph (there are exactly three edges at each vertex) and a symmetric graph (every incident pair of a vertex and an edge can be transformed into every other such pair by a symmetry of the graph). The girth of this structure is 10 — the shortest cycles in the graph have 10 vertices — and 15 of these cycles pass through each vertex.[1][3][11]

The cells of the Voronoi diagram of this structure are heptadecahedra with 17 faces each. They are plesiohedra, polyhedra that tile space isohedrally. Experimenting with the structures formed by these polyhedra led Alan Schoen to discover the gyroid minimal surface.[12]

One of the four cubic induced subgraphs of the unit distance graph on the three-dimensional integer lattice having a girth of 10 is isomorphic to the Laves graph.[13]

Physical examples[]

Molecular crystals[]

Computations suggest that the Laves graph can serve as the pattern for a metastable or perhaps unstable allotrope of carbon.[5][8] Like graphite, each atom in the structure is bonded to three others, but in graphite adjacent atoms have the same bonding planes as each other whereas in this structure the bonding planes of adjacent atoms are twisted with respect to each other around the line formed by the bond, with a twisting angle of approximately 70.5°.

The Laves graph may also give a crystal structure for boron; computations predict that this should be stable.[14] Other chemicals that may form this structure include SrSi2, and elemental nitrogen.[11][14]

Other[]

The structure of the Laves graph, and of gyroid surfaces derived from it, has also been observed experimentally in soap-water systems, and in the chitin networks of butterfly wing scales.[11]

References[]

- ^ a b c d e f Sunada, Toshikazu (2008), "Crystals that nature might miss creating" (PDF), Notices of the American Mathematical Society, 55 (2): 208–215, MR 2375022. Sunada, Toshikazu (2008), "Correction: Crystals that nature might miss creating" (PDF), Notices of the American Mathematical Society, 55 (3): 343.

- ^ a b Biggs, N. L. (1984), "Homological coverings of graphs", Journal of the London Mathematical Society, Second Series, 30 (1): 1–14, doi:10.1112/jlms/s2-30.1.1, MR 0760867.

- ^ a b c Coxeter, H. S. M. (1955), "On Laves' graph of girth ten", Canadian Journal of Mathematics, 7: 18–23, doi:10.4153/CJM-1955-003-7, MR 0067508.

- ^ Laves, F. (1932), "Zur Klassifikation der Silikate. Geometrische Untersuchungen möglicher Silicium-Sauerstoff-Verbände als Verknüpfungsmöglichkeiten regulärer Tetraeder", Zeitschrift für Kristallographie, 82 (1): 1–14, doi:10.1524/zkri.1932.82.1.1.

- ^ a b Itoh, Masahiro; Kotani, Motoko; Naito, Hisashi; Sunada, Toshikazu; Kawazoe, Yoshiyuki; Adschiri, Tadafumi (2009), "New metallic carbon crystal", Physical Review Letters, 102 (5): 055703, Bibcode:2009PhRvL.102e5703I, doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.102.055703, PMID 19257523.

- ^ a b Hart, George W., The (10, 3)-a Network, retrieved 2014-11-30.

- ^ Wells, A. F. (1940), "X. Finite complexes in crystals: a classification and review", The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science, Series 7, 30 (199): 103–134, doi:10.1080/14786444008520702.

- ^ a b Tagami, Makoto; Liang, Yunye; Naito, Hisashi; Kawazoe, Yoshiyuki; Kotani, Motoko (2014), "Negatively curved cubic carbon crystals with octahedral symmetry", Carbon, 76: 266–274, doi:10.1016/j.carbon.2014.04.077.

- ^ Lanier, Jaron (2009), "From planar patterns to polytopes", American Scientist.

- ^ Séquin, Carlo H. (2008), "Intricate Isohedral Tilings of 3D Euclidean Space", in Sarhangi, Reza; Séquin, Carlo H. (eds.), Bridges Leeuwarden: Mathematics, Music, Art, Architecture, Culture, London: Tarquin Publications, pp. 139–148, ISBN 9780966520194.

- ^ a b c d e Hyde, Stephen T.; O'Keeffe, Michael; Proserpio, Davide M. (2008), "A short history of an elusive yet ubiquitous structure in chemistry, materials, and mathematics" (PDF), Angewandte Chemie International Edition, 47 (42): 7996–8000, doi:10.1002/anie.200801519, PMID 18767088.

- ^ Schoen, Alan H. (June–July 2008), "On the graph (10,3)-a" (PDF), Notices of the American Mathematical Society, 55 (6): 663.

- ^ Haugland, Jan Kristian (2003), "Classification of certain subgraphs of the 3-dimensional grid", Journal of Graph Theory, 42: 34–60, doi:10.1002/jgt.10071.

- ^ a b Dai, Jun; Li, Zhenyu; Yang, Jinlong (2010), "Boron K4 crystal: a stable chiral three-dimensional sp2 network", Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics, 12 (39): 12420–12422, Bibcode:2010PCCP...1212420D, doi:10.1039/C0CP00735H, PMID 20820588.

External links[]

- Baez, John (October 14, 2016), "Laves Graph", Visual Insight, American Mathematical Society

- Crystallography

- Infinite graphs

- Regular graphs