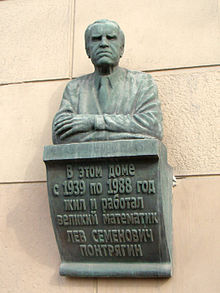

Lev Pontryagin

Lev Pontryagin | |

|---|---|

Lev Semenovich Pontryagin (left) | |

| Born | 3 September 1908 |

| Died | 3 May 1988 (aged 79) |

| Nationality | Soviet Union |

| Known for | Pontryagin duality Pontryagin class Pontryagin cohomology operation Pontryagin's maximum principle Andronov–Pontryagin criterion |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Mathematics |

| Doctoral advisor | Pavel Alexandrov |

| Doctoral students | Dmitri Anosov Vladimir Boltyansky Revaz Gamkrelidze Mikhail Postnikov Mikhail Zelikin |

Lev Semyonovich Pontryagin (Russian: Лев Семёнович Понтрягин, also written Pontriagin or Pontrjagin) (3 September 1908 – 3 May 1988) was a Soviet mathematician. He was born in Moscow and lost his eyesight completely due to an unsuccessful eye surgery after a primus stove explosion when he was 14. Despite his blindness he was able to become one of the greatest mathematicians of the 20th century, partially with the help of his mother Tatyana Andreevna who read mathematical books and papers (notably those of Heinz Hopf, J. H. C. Whitehead, and Hassler Whitney) to him. He made major discoveries in a number of fields of mathematics, including algebraic topology and differential topology.

Work[]

Pontryagin worked on duality theory for homology while still a student. He went on to lay foundations for the abstract theory of the Fourier transform, now called Pontryagin duality. With René Thom, he is regarded as one of the co-founders of cobordism theory, and co-discoverers of the central idea of this theory, that framed cobordism and stable homotopy are equivalent.[1] This led to the introduction around 1940 of a theory of certain characteristic classes, now called Pontryagin classes, designed to vanish on a manifold that is a boundary. In 1942 he introduced the cohomology operations now called Pontryagin squares. Moreover, in operator theory there are specific instances of Krein spaces called Pontryagin spaces.

Later in his career he worked in optimal control theory. His maximum principle is fundamental to the modern theory of optimization. He also introduced there the idea of a bang-bang principle, to describe situations where the applied control at each moment is either the maximum 'steer', or none.[citation needed]

Pontryagin authored several influential monographs as well as popular textbooks in mathematics.

Pontryagin's students include Dmitri Anosov, Vladimir Boltyansky, Revaz Gamkrelidze, Evgeni Mishchenko, Mikhail Postnikov, Vladimir Rokhlin, and Mikhail Zelikin.

Controversy and anti-semitism allegations[]

Pontryagin was accused of anti-Semitism on several occasions. For example, he attacked Nathan Jacobson for being a "mediocre scientist" representing the "Zionism movement", while both men were vice-presidents of the International Mathematical Union.[2][3] He rejected charges of anti-Semitism in an article published in Science in 1979,[4] claiming that he struggled with Zionism, which he considered a form of racism.[3] When a prominent Soviet Jewish mathematician, Grigory Margulis, was selected by the IMU to receive the Fields Medal at the upcoming 1978 ICM, Pontryagin, who was a member of the Executive Committee of the IMU at the time, vigorously objected.[5] Although the IMU stood by its decision to award Margulis the Fields Medal, Margulis was denied a Soviet exit visa by the Soviet authorities and was unable to attend the 1978 ICM in person.[5] Pontryagin also participated in a few notorious political campaigns in the Soviet Union, most notably, in the Luzin affair.

Publications[]

- Pontrjagin, L. (1939), Topological Groups, Princeton Mathematical Series, 2, Princeton: Princeton University Press, MR 0000265 (translated by Emma Lehmer)[6]

- 1952 - Foundations of Combinatorial Topology (translated from 1947 original Russian edition)[7] 2015 Dover reprint[8]

- 1962 - Ordinary Differential Equations (translated from Russian by Leonas Kacinskas and Walter B. Counts)[9]

- Pontryagin, L. S. (15 May 2014). Ordinary Differential Equations: Adiwes International Series in Mathematics. ISBN 9781483156491.

- 1962 - with Vladimir Boltyansky, Revaz Gamkrelidze, and : The Mathematical Theory of Optimal Processes[10]

See also[]

- Andronov–Pontryagin criterion

- Kuratowski's theorem, also called the Pontryagin–Kuratowski theorem

- Pontryagin class

- Pontryagin duality

- Pontryagin's maximum principle

Notes[]

- ^ Mackenzie, Dana (2010), What's Happening in the Mathematical Sciences, Volume 8, American Mathematical Society, p. 126, ISBN 9780821849996.

- ^ O'Connor, John J; Edmund F. Robertson "Nathan Jacobson". MacTutor History of Mathematics archive.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Memoirs, by Lev Pontryagin, Narod Publications, Moscow, 1998 (in Russian).

- ^ Pontryagin, LS (September 14, 1979). "Soviet Anti-Semitism: Reply by Pontryagin". Science. 205 (4411): 1083–1084. Bibcode:1979Sci...205.1083P. doi:10.1126/science.205.4411.1083. PMID 17735029.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Olli Lehto. Mathematics without borders: a history of the International Mathematical Union. Springer-Verlag, 1998. ISBN 0-387-98358-9; pp. 205-206

- ^ Puckett Jr, W. T. (1940). "Book Review: Topological Groups". Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society. 46 (5): 382–385. doi:10.1090/S0002-9904-1940-07199-X.

- ^ Massey, W. S. (1953). "Book Review: Foundations of combinatorial topology". Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society. 59 (2): 188–190. doi:10.1090/S0002-9904-1953-09702-6.

- ^ Satzer, William J. (October 21, 2015). "Review of Foundations of combinatorial topology". MAA Reviews, Mathematical Association of America.

- ^ Brauer, Fred (June 1964). "Review of Ordinary Differential Equations by L. S. Pontryagin". Canadian Mathematical Bulletin. 7 (2): 315–316. doi:10.1017/S0008439500027119. page 316

- ^ Blum, Edward Kenneth (December 1963). "Reviewed Work: The Mathematical Theory of Optimal Processes by Pontryagin, Boltyanskii, Gamkrelidze, Mishchenko". The American Mathematical Monthly. 70 (10): 1114–1116. doi:10.2307/2312867. JSTOR 2312867.

External links[]

- Lev Pontryagin at the Mathematics Genealogy Project

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Lev Pontryagin", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews

- Autobiography of Pontryagin (in Russian)

- Kutateladze S. S., Sic Transit... or Heroes, Villains, and Rights of Memory.

- Kutateladze S. S., The Tragedy of Mathematics in Russia

- 1908 births

- 1988 deaths

- Blind people from Russia

- Control theorists

- Heroes of Socialist Labour

- Soviet mathematicians

- Full Members of the USSR Academy of Sciences

- Blind academics

- 20th-century Russian mathematicians

- Soviet people

- Moscow State University faculty