Little House on the Prairie

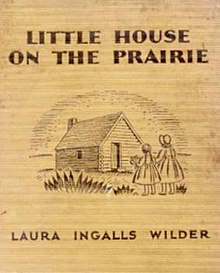

Front hardcover, first edition of the most frequently adapted volume (1935) | |

| Author | Laura Ingalls Wilder |

|---|---|

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Fiction |

| Publisher | Harper & Brothers |

| Published | 1932–1943, 1971 |

| No. of books | 9 |

The "Little House" Books is a series of American children's novels written by Laura Ingalls Wilder, based on her childhood and adolescence in the American Midwest (Wisconsin, Kansas, Minnesota, South Dakota, and Missouri) between 1870 and 1894.[1] Eight of the novels were completed by Wilder, and published by Harper & Brothers. The appellation "Little House" books comes from the first and third novels in the series of eight published in her lifetime. The second novel was about her husband's childhood. The first draft of a ninth novel was published posthumously in 1971 and is commonly included in the series.[2]

The Little House books have been adapted for stage or screen more than once, most successfully as the American television series Little House on the Prairie, which ran from 1974 to 1983.[3] As well as an anime and many spin-off books, there are cookbooks and various other licensed products representative of the books.[4]

A tenth book, the non-fiction On the Way Home, is Laura Ingalls Wilder's diary of the years after 1894, when she, her husband and their daughter moved from De Smet, South Dakota to Mansfield, Missouri, where they settled permanently. It was published in 1962 and includes commentary by Rose Wilder Lane.

History[]

Publishing[]

The first book of the Little House series, Little House in the Big Woods, was published in 1932.[5] This first book did well when it was first published.[6] The Little House books were reissued by Ursula Nordstrom to be illustrated by Garth Williams.[7]

Before writing the Little House series Laura Ingalls Wilder was a columnist in a farm journal.[6] Her daughter, Rose Wilder Lane, was the motivator behind Wilder's writing and publishing of the first book.[5] Since the first book, there have been around 60 million Little House books sold.[5] There are 9 books that fall under the Little House books umbrella.[8]

Rose Wilder Lane had a heavy hand in the editing of the books, though Laura Ingalls Wilder's voice is still strong.[6] It is contested the amount of influence that Lane had on the books, especially regarding any political themes, but views that align with hers are very visible within the books.[5] Regardless, Rose Wilder Lane was a large part in the publishing and form of the books. Lane also had a hand in giving the rights to Roger Lea MacBride, who then led to the creation of the television show entitled Little House on the Prairie.[5]

Time ranks the Little House series as 22 out of 100 of the "100 Best Young Adult Books of All Time."[9] They are considered classics of American children's literature and remain widely read. In a 2012 survey published by School Library Journal, a monthly with primarily U.S. audience, Little House in the Big Woods was ranked number 19 among all-time best children's novels, and two of its sequels were ranked among the top 100.[10] Five of the Little House book have been Honor Books for the Newbery Medal. In 1938, On the Banks of Plum Creek, was an Honor Book; in 1940 By the Shores of Silver Lake was as well. Later in 1941, The Long Winter, became an Honor Book, and the two later Honor Books were The Little Town on the Prairie, in 1942, and Those Happy Golden Years in 1944.[11] In addition to this, the American Library Association stated that The Long Winter, the seventh book in the series, was a "resource for teaching about pioneer history."[12]

Depiction of minorities[]

The Little House books include people from ethnic minorities, including a heroic black doctor who saves the protagonist's family. However, there have been criticisms of the Little House books because of portrayals of Native Americans.[13] Much of the criticism relates to some of the characters expressing negative stereotypes as well as a view of them as less than human.[14] There has also been criticism of the ignorance present in the books of the illegality of the Ingalls' occupation of land they did not have the right to occupy.[14]

An incident concerning Wilder's depiction of Native Americans occurred in 1998, when an eight-year-old girl read Little House on the Prairie in her elementary school class. In the book, a minor character says "The only good Indian is a dead Indian," to which Pa replies that "he didn't know abbout that. He figured that Indians would be as peacable as anybody else if they were let alone." The girl's mother, Waziyatawin Angela Cavender Wilson, a member of the Wahpetunwan Dakota nation, challenged the school on its use of the book in the classroom.[15] This was one of many statements and actions that prompted the American Library Association to investigate and ultimately change the name of the Wilder Award to the Children's Literature Legacy Award.[15][16] This award is given to books that have made a large impact on children's literature in America.[17]

Accuracy to history[]

Laura Ingalls Wilder's work is autobiographical fiction and Wilder employed artistic licence, including creating composite characters based on multiple real individuals[14] and presenting a subjective view of her family's experiences.[18] It has been criticized regarding the history of the government's involvement in homesteading,[18] and its effect upon Native American people,[14] including her family's occupation of land which was still recognized by the United States government as the Osage Nation's territory.[14]

Connections with politics[]

While Laura Ingalls Wilder wrote the Little House books, it was Rose Wilder Lane who edited them and it was Lane who had the rights after Wilder's death. Rose was an "outspoken antigovernment polemicist and is called one of the grandmothers of the libertarian movement."[5] Lane's views were supported by her mother.[6] Despite her mother's support of her political views, Lane went against her mother and what was written in her will by leaving the rights of the Little House books to Roger Lea MacBride after her own death.[6] Roger Lea MacBride has strong connections to politics, being a once libertarian presidential candidate, and a member of the Republican Liberty Caucus.[5] He gained the rights to the books not only from Lane's will but also through a legal battle with the library that Wilder wrote in her will should gain the rights after Lane's death.[5] It was MacBride who allowed the television show to be made and who talked about Laura's books, and through the rights he made a great deal of money.[5]

Another political issue raised by the practice of homesteading as described in the Little House books is John Locke's Labor Theory of Property, which is the idea that if someone improves the land with their own labor that they then have rights to that land.[19]

Depiction of the United States Government[]

Anti-governmental political views, such as those held by Rose Wilder Lane, have been attributed to the Little House books. In her article, "Little House on the Prairie and the Truth About the American West", historian Patricia Nelson Limerick connects Wilder's apparent and Lane's outright distaste for the government as a way to blame the government for their father's failure at homesteading.[6] The books show the Wilder family to be entrepreneurs and show a form of hero worship of Laura Ingalls Wilder's parents.[18] In "Little House on the Prairie and the Myth of Self Reliance", Julie Tharp and Jeff Kleiman say that the idea of the settlers' self-reliance, which they consider to be a myth, has contributed to conservative rhetoric, and that the Little House books are full of this myth.[18]

Books[]

- Little House in the Big Woods (1932)

- Farmer Boy (1933)

- Little House on the Prairie (1935)

- On the Banks of Plum Creek (1937)

- By the Shores of Silver Lake (1939)

- The Long Winter (1940)

- Little Town on the Prairie (1941)

- These Happy Golden Years (1943)

- The First Four Years (1971)

Four series of books expand the Little House series to include five generations of Laura Ingalls Wilder's family. The "Martha Years" and "Charlotte Years" series, by Melissa Wiley, are fictionalized tales of Laura's great-grandmother in Scotland in the late 18th century and grandmother in early 19th century Massachusetts.[20] The "Caroline Years" series narrates Wilder's mother, Caroline Quiner's, childhood in Wisconsin.[21] The Rose Years (originally known as the "Rocky Ridge Years") series follows Rose Wilder Lane from childhood in Missouri to early adulthood in San Francisco. It was written by her surrogate grandson Roger MacBride.[22]

Two volumes of Wilder's letters and diaries have also been issued under the Little House imprint: On The Way Home and West From Home, published by Harper Collins in 1962 and 1974 respectively.[23][24]

Little House in the Big Woods[]

Little House in the Big Woods was published in 1932. Written by Laura Ingalls Wilder, the book is autobiographical, though some parts of the story were embellished or changed to appeal more to an audience, such as Laura’s age. In the book, Laura herself turns five years old, when the real-life author had only been three during the events of the book. According to a letter from her daughter, Rose, to biographer William Anderson, the publisher had Laura change her age in the book because it seemed unrealistic for a three-year-old to have specific memories such as she wrote about.[25] The story of Little House in the Big Woods, revolves around the life of the Ingalls family. The family includes mother Caroline Ingalls, father Charles Ingalls, elder daughter Mary Amelia Ingalls, and younger daughter (and protagonist), Laura Ingalls Wilder.[26] Also in the story, though not yet born historically, is Laura's baby sister Carrie.

The setting of this book is different from the rest of the series, as the story takes place in the Ingalls' small cabin in the state of Wisconsin, near a town called Pepin. Little House in the Big Woods describes the homesteading skills Laura observed and began to practice during her fifth year. The cousins come for Christmas that year, and Laura receives a doll, which she names Charlotte. Later that winter, the family goes to Grandma Ingalls’ home and has a “sugaring off,” when they harvest sap and make maple syrup. They return home with buckets of syrup, enough to last the year. Laura remembered that sugaring off and the dance that followed for the rest of her life.[27]

The book also describes other farm work duties and events, such as the birth of a calf; the availability of milk, butter and cheese; gardening; field work; hunting; gathering; and more. Everyday housework is also described in detail. When Pa went into the woods to hunt, he usually came home with a deer and then smoked the meat for the coming winter. One day he noticed a bee tree and returned from hunting early to get the wash tub and milk pail to collect the honey. When Pa returned home on winter evenings, Laura and Mary always begged him to play his fiddle, but he was too tired from farm work to play during the summertime.[27] Later in the series, the family moved away from Wisconsin to a homestead in Kansas, as territory in the West was being given to settlers. Later they moved on to Minnesota. This reflects the time period in the 1800's during which farmers and many others were migrating westward into the American frontier.

Farmer Boy[]

Farmer Boy was published in 1933. It is the second Little House book, although its story is unrelated to the first few books in the series. It features a different protagonist named Almanzo Wilder, who later became Laura’s husband. In Farmer Boy, Almanzo is featured from before his ninth birthday until after his tenth. Throughout the novel, Laura recounts the experiences and adventures of Almanzo in his late childhood and adolescence. Living in a successful farm in the state of New York in the late 19th century, Almanzo endures hardships such as the long 1.5 mi (2.4 km) walk to school with his older siblings. Through Farmer Boy, readers catch a glimpse of the daily routine of early farmers, and learn about activities such as candle making, shearing sheep, threshing wheat, and even making donuts. The story also walks readers through Almanzo’s favorite pastimes, which include sledding, berry picking, swimming, and fishing. [28]

Little House on the Prairie[]

Little House on the Prairie, published in 1935, is the third book in the Little House series but only the second that features the Ingalls family; it continues directly the story of the inaugural novel, Little House in the Big Woods.

The book tells about the months the Ingalls family spent on the prairie of Kansas, around the town of Independence, Kansas. At the beginning of this story, Pa Ingalls decides to sell the house in the Big Woods of Wisconsin and move the family, via covered wagon,to the Indian Territory near Independence, Kansas, as there were widely circulating stories that the land (under Osage ownership) would be opened to settlement by homesteaders imminently. So Laura, along with Pa and Ma, Mary, and baby Carrie, move to Kansas. Along the way, Pa trades his two horses for two Western mustangs, which Laura and Mary name Pet and Patty.[29]

When the family reaches Indian Territory, they meet Mr. Edwards, who is extremely polite to Ma but tells Laura and Mary that he is "a wildcat from Tennessee." Mr. Edwards is an excellent neighbor, who helps the Ingalls in every way he can, beginning with helping Pa erect their house. Pa builds a roof and a floor for their house and digs a well, and the family is finally settled.[29]

At their new home, unlike their time in the Big Woods, the family meets difficulty and danger. The Ingalls family becomes terribly ill from a disease called at that time "fever 'n' ague" (fever with severe chills and shaking), which was later identified as malaria. Laura comments on the varied ways they believe to have acquired it, with "Ma" believing it came from eating bad watermelon. Mrs. Scott, another neighbor, takes care of the family while they are sick. Around this time, Mr. Edwards brings Laura and Mary their Christmas presents from Independence, and in the spring the Ingallses plant the beginnings of a small farm.[29]

Ma's fears about American Indians and Laura's observations at the time are contrasted with Pa's liberal view of them, and all these views are shown side by side with the older Laura's objective portrayal of the Osage tribe that lived on that land.[14]

At the end of this book, the family is told that the land must be vacated by settlers as it is not legally open to settlement yet, and in 1870 Pa elects to leave the land and move before the Army forcibly requires him to abandon the land.[29]

On the Banks of Plum Creek[]

On the Banks of Plum Creek, published in 1937 and fourth in the series, follows the Ingalls family as they move from Pepin, Wisconsin to Kansas to an area near Walnut Grove, Minnesota, and settle in a dugout "on the banks of Plum Creek (Redwood County, Minnesota)".[30]

Pa trades his horses Pet and Patty to the property owner (a man named Hanson) for the land and crops, but later he gets two new horses as Christmas presents for the family, and Laura and her sister Mary name them "Sam" and "David". Pa soon builds a new, above-ground, wooden house for the family. During this story, Laura and Mary go to school in town for the first time, and they meet their teacher, Miss Eva Beadle. They also meet Nellie Oleson, who makes fun of Laura and Mary for being "country girls". Laura plays with her bulldog Jack when she is home, and she and Mary are invited to a party at the Olesons' home. Laura and Mary invite all the girls (including Nellie) to a party at their house to reciprocate. The family soon goes through hard times when a plague of Rocky Mountain locusts decimates their crops. The book ends with Pa returning safely to the house after being unaccounted for during a severe four-day blizzard.[31]

By the Shores of Silver Lake[]

By the Shores of Silver Lake was published in 1939 and is fifth in the series.

The story begins when the family is about to leave Plum Creek shortly after the family has recovered from the scarlet fever which caused Mary to become blind. The family welcomes a visit from Aunt Docia, whom they had not seen for several years. She suggests that Pa and Ma move west to the rapidly developing Dakota Territory, where Pa could work in Uncle Henry’s railroad camp at very good wages for that era. Ma and Pa agree, since it will allow Pa to look for a homestead while he works. The family has endured many hardships at Plum Creek, and Pa especially is anxious for a new start. After selling his land and farm to neighbors, Pa goes ahead with the wagon and team. Mary is still too weak to travel, so the rest of the family follows later by train.[32]

The day Pa leaves, however, their beloved bulldog Jack is found dead, which saddens Laura greatly. In actuality, the dog upon whom Jack was based was no longer with the family at this point, but the author inserted his death here to serve as a transition between her childhood and her adolescence. Laura also begins to play a more mature role in the family due to Mary's blindness. Pa instructs Laura to "be Mary's eyes" and to assist her in daily life as she learns to cope with her disability. Mary is strong and willing to learn.[32]

The family travels to Dakota Territory by train. This is the children's first train trip and they are excited by the novelty of this new mode of transportation that allows them to travel in one hour the distance it would take a horse and wagon an entire day to cover.[32]

With the family reunited and situated at the railroad camp, Laura meets her cousin Lena, and the two become good friends.[32]

As winter approaches and the railroad workers take down the cabins and head back east, the family wonders where they might stay for the winter. As luck would have it, the county surveyor needs a house-sitter while he is back east for the winter, and Pa signs up. It is a winter of luxury for the Ingalls family as they are given all the provisions they need in the large, comfortable house. They spend a cozy winter with their new friends, Mr. and Mrs. Boast, and both families look forward to starting their new claims in the spring.[32]

But the "spring rush" comes early. The large mobilization of pioneers to the Dakotas in early March prompts Pa to leave immediately on the few days' trip to the claims office. The girls are left alone to spend their days and nights boarding and feeding all the pioneers passing through. They charge 25 cents for dinner and boarding and start a savings account toward sending Mary to the School for the Blind in Vinton, Iowa.[32]

Pa successfully files his claim, with the aid of old friend Mr. Edwards. As the spring flowers bloom and the prairie comes alive with new settlers, the Ingalls family moves to their new piece of land and begins building what will become their permanent home.[32]

The Long Winter[]

The Long Winter, published in 1940 and sixth in the series, covers the shortest time span of the novels, only an eight-month period. The winter of 1880–1881 was a notably severe winter in history, sometimes known as "The Snow Winter."[33][34][35]

The story begins in Dakota Territory at the Ingalls homestead in South Dakota on a hot September day in 1880 as Laura and her father ("Pa") are haying. Pa tells Laura that he knows the winter is going to be hard because muskrats always build a house with thick walls before a hard winter, and this year they have built the thickest walls he has ever seen. In mid October the Ingallses wake with an unusually early blizzard howling around their poorly insulated claim shanty. Soon afterward, Pa receives another warning from an unexpected source: a dignified old Native American man comes to the general store in town to warn the white settlers that there will be seven months of blizzards. Impressed, Pa decides to move the family into town for the winter.[36]

Laura attends school with her younger sister Carrie until the weather becomes too severe to permit them to walk to and from the school building. Blizzard after blizzard sweeps through the town over the next few months. Food and fuel become scarce and expensive, as the town depends on the trains to bring supplies but the frequent blizzards prevent the trains from getting through. Eventually, the railroad company suspends all efforts to dig out the train, stranding the town. For weeks, the Ingallses subsist on potatoes and coarse brown bread, using twisted hay for fuel. As even this meager food runs out, Laura's future husband Almanzo Wilder and his friend Cap Garland risk their lives to bring wheat to the starving townspeople – enough to last the rest of the winter.[36]

Laura's age in this book is accurate. (In 1880, she would have been 13, as she states in the first chapter.) However, Almanzo Wilder's age is misrepresented in this book. Much is made of the fact that he is 19 pretending to be 21 in order to illegally obtain a homestead claim from the US government. But in 1880, his true age would have been 23. Scholar Ann Romines has suggested that Laura made Almanzo younger because it was felt that more modern audiences would be scandalized by the great difference in their ages in light of their young marriage.[37]

As predicted, the blizzards continue for seven months. Finally, the trains begin running again, bringing the Ingallses a Christmas barrel full of good things, including a turkey. In the last chapter, they sit down to enjoy their Christmas dinner in May.[36]

Little Town on the Prairie[]

Little Town on the Prairie, published in 1941 is seventh in the series.

The story begins as Laura accepts her first job performing sewing work in order to earn money for Mary to go to a college for the blind in Iowa. Laura's hard work comes to an end by summer when she is let go, and the family begins planning to raise cash crops to pay for Mary's college. After the crops are destroyed by blackbirds, Pa sells a calf to earn the balance of the money needed. When Ma and Pa escort Mary to the college, Laura, Carrie, and Grace are left alone for a week. In order to stave off the loneliness stemming from Mary's departure, Laura, Carrie, and Grace do the fall cleaning. They have several problems, but the house is sparkling when they are done. Ma and Pa come home, and are truly surprised.[38]

In the fall, the Ingallses quickly prepare for a move to town for the winter. Laura and Carrie attend school in town, and Laura is reunited with her friends Minnie Johnson and Mary Power, and she meets a new girl, Ida Brown. There is a new schoolteacher for the winter term: Eliza Jane Wilder, Almanzo’s sister. Nellie Oleson, Laura's nemesis from Plum Creek, has moved to De Smet and is attending the school. Nellie turns the teacher against Laura, and Miss Wilder loses control of the school for a time. A visit by the school board restores order; however, Miss Wilder leaves at the end of the fall term, and she is eventually replaced by Mr. Clewett and then by Mr. Owen, the latter of whom befriends Laura. Through the course of the winter, Laura sets herself to studying, as she only has one year left before she can apply for a teaching certificate.[38]

At the same time, Almanzo Wilder begins escorting Laura home from church. By Christmas, Almanzo has offered to take Laura on a sleigh ride after he completes the cutter he is building.[38]

At home, Laura is met by Mr. Boast and Mr. Brewster, who ask Laura if she would be interested in a teaching position at a settlement led by Brewster, twelve miles (19 km) from town. The school superintendent, George Williams, comes and tests Laura. Though she is two months too young, he never asks her age. She is awarded a third-grade teaching certificate.[38]

These Happy Golden Years[]

These Happy Golden Years, published in 1943 and eighth in the series, originally ended with a note alone on the last page: "The end of the Little house books."[39] It takes place between 1882 and 1885. As the story begins, Pa is taking Laura 12 miles (19 km) from home to her first teaching assignment at the Brewster settlement. Laura, only 15 and a schoolgirl herself, is apprehensive, as this is both the first time she has left home and the first school at which she has taught. She is determined to complete her assignment and earn $40 to help her sister Mary, who is attending Vinton College for the Blind in Iowa.[40]

This first assignment proves difficult for her. Laura must board with the Brewsters in their two-room claim shanty, sleeping on their sofa. The Brewsters are an unhappy family, and Laura is deeply uncomfortable observing husband and wife quarrel. In one particularly unsettling incident, she wakes in the night to see Mrs. Brewster standing over her husband with a knife. It is a bitterly cold winter, and neither the claim shanty nor the school house can be heated adequately. The children she is teaching, some of whom are older than she is herself, test her skills as a teacher. Laura grows more self-assured, and she successfully completes the two-month term.[40]

To Laura's surprise and delight, homesteader Almanzo Wilder (with whom she became acquainted in Little Town on the Prairie) appears at the end of her first week of school in his new two-horse cutter to bring her home for the weekend. Already fond of Laura and wanting to ease her homesickness, Almanzo takes it upon himself to bring her home and back to school each weekend.[40]

The relationship continues after the school term ends. Sleigh rides give way to buggy rides in the spring, and Laura impresses Almanzo with her willingness to help break his new and often temperamental horses. Laura's old nemesis, Nellie Oleson, makes a brief appearance during two Sunday buggy rides with Almanzo. Nellie's chatter and flirtatious behavior towards Almanzo annoy Laura. Shortly thereafter, Nellie moves back to New York after her family loses its homestead.[40]

Laura's Uncle Tom (Ma's brother) visits the family and tells of his failed venture with a covered-wagon brigade seeking gold in the Black Hills. Laura helps out seamstress Mrs. McKee by staying with her and her daughter on their prairie claim for two months to "hold it down" as required by law. The family enjoys summer visits from Mary.[40]

The family finances have improved to the point that Pa can sell a cow to purchase a sewing machine for Ma. Laura continues to teach and work as a seamstress.[40]

Almanzo invites Laura to attend summer "singing school" with him and her classmates. On the last evening of singing school, while driving Laura home, Almanzo, after courting Laura for three years, proposes to her. During their next ride, Almanzo presents Laura with a garnet-and-pearl ring and they share their first kiss.[40]

Several months later, after Almanzo has finished building a house on his tree claim, he asks Laura if she would mind getting married within a few days, as his sister and his mother have their hearts set on a large church wedding, which Pa cannot afford. Laura agrees, and she and Almanzo are married in a simple ceremony by the Reverend Brown. After a wedding dinner with her family, Laura drives away with Almanzo, and the newlyweds settle contentedly into their new home.[40]

The First Four Years[]

The First Four Years, published in 1971, is commonly considered the ninth and last book in the original Little House series. It covers the earliest years of Laura and Almanzo's marriage.[41]

The First Four Years derives its title from a promise Laura made to Almanzo when they became engaged. Laura did not want to be a farm wife, but she consented to try farming for three years. At the end of that time, Laura and Almanzo mutually agreed to continue for one more year, a "year of grace", in Laura's words. The book ends at the close of that fourth year, on a rather optimistic note. In reality, the continually hot, dry Dakota summers, and several other tragic events described in the book eventually drove them from their land, but they later founded a very successful fruit and dairy farm in Missouri, where they lived comfortably until their respective deaths.[41]

Related books[]

- On the Way Home (1962)

- West from Home (1974)

- Little House on Rocky Ridge (1993)

- Little Farm in the Ozarks (1994)

- In the Land of the Big Red Apple (1995)

- On the Other Side of the Hill (1995)

- Little Town in the Ozarks (1996)

- New Dawn on Rocky Ridge (1997)

- On the Banks of the Bayou (1998)

- Bachelor Girl (1999)

- The Road Back (2006)

Television adaptations[]

Jackanory (1966, 1968)[]

Jackanory is a British television series intended to encourage children to read; it ran from 1965 to 1996, and was revived in 2006. From October 24 through October 28, 1966, five short episodes aired that were based on Little House in the Big Woods, with Red Shively as the storyteller. From October 21 through October 25, 1968, five more were released, this time based on Farmer Boy, with Richard Monette as the storyteller.

Little House on the Prairie (TV series, 1974–1983)[]

The television series Little House on the Prairie aired on the NBC network from 1974 to 1983. The show was a loose adaptation of Laura Ingalls Wilder's Little House on the Prairie semi-autobiographical novel series, although the namesake book was represented in the premiere only; the ensuing television episodes primarily followed characters and locations from the follow-up book, On the Banks of Plum Creek (1937), although the continuity of the television series greatly departed from this book as well. Some storylines were borrowed from Wilder's later books but were portrayed as having taken place in the Plum Creek setting. Michael Landon starred as Charles Ingalls, Karen Grassle played Caroline Ingalls, Melissa Gilbert played Laura Ingalls, Melissa Sue Anderson played Mary Ingalls, and the twins Lindsay and Sidney Greenbush (credited as Lindsay Sidney Greenbush) played Carrie Ingalls. Victor French portrayed long-time friend Mr. Edwards. Dean Butler portrayed Laura's husband, Almanzo Wilder. Some characters were added in the show, such as Albert, played by Matthew Laborteaux, an orphan whom the family adopted.[3]

Although it deviated from the original books in many respects, the television series, which was set in Walnut Grove, Minnesota, was one of a few long-running successful dramatic family shows.[citation needed] It remained a top-rated series, and garnered 17 Emmy and three Golden Globe nominations, along with two People’s Choice Awards.[42]

Laura, the Prairie Girl (animated series, 1975)[]

A Japanese anime television series of 26 episodes (about 24 minutes each), originally entitled Sōgen no Shōjo Laura.

Beyond the Prairie (2000, 2001)[]

Two made for television movies by Marcus Cole, with Meredith Monroe as Laura. Part 1 tells the story of teenage Laura in DeSmet, while the second part is about Laura and Almanzo's (Walton Goggins) marriage and their life in Mansfield, Missouri. It also focuses a lot on the character of Wilder's young daughter; Rose (Skye McCole Bartusiak).[43]

Little House on the Prairie (2005 miniseries)[]

The 2005 ABC five-hour (six-episode) miniseries Little House on the Prairie attempted to follow closely the books Little House in the Big Woods and Little House on the Prairie. It starred Cameron Bancroft as Charles Ingalls; Erin Cottrell as Caroline Ingalls; Kyle Chavarria as Laura Ingalls; Danielle Chuchran as Mary Ingalls; and Gregory Sporleder as Mr Edwards. It was directed by David L. Cunningham. In 2006 the mini-series was released on DVD and the 2-disc set runs approximately 255 minutes long.[44]

Stage adaptation[]

A musical version of the Little House books premiered at the Guthrie Theater, Minnesota on July 26, 2008. The musical has music by Rachel Portman and lyrics by and is directed by Francesca Zambello with choreography by Michele Lynch. The cast includes Melissa Gilbert as "Ma". The musical began a US national tour in October 2009.[45][46]

Documentary[]

Little House on the Prairie: The Legacy of Laura Ingalls Wilder is a one-hour documentary film that looks at the life of Wilder. Wilder's story as a writer, wife, and mother is explored through interviews with scholars and historians, archival photography, paintings by frontier artists, and dramatic reenactments.[47]

See also[]

References[]

- ^ Fraser, Caroline (2017). Prairie Fires. New York: Metropolitan Book. p. 2. ISBN 9781627792769.

- ^ Anderson, William (1992). Laura Ingalls Wilder: A Biography. New York: Harper Trophy. pp. 13. ISBN 978-0-06-020113-5.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Little House on the Prairie, Melissa Gilbert, Michael Landon, Karen Grassle, retrieved April 11, 2018CS1 maint: others (link)

- ^ Fraser, Caroline (2017). Prairie Fires. New York: Metropolitan Books. p. 4.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i Russo, Maria (February 7, 2017). "Finding America, Both Red and Blue, in the 'Little House' Books". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 10, 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Limerick, Patricia Nelson (November 20, 2017). "'Little House on the Prairie' and the Truth About the American West". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 10, 2018.

- ^ Larson, Sarah (June 3, 2016). "Garth Williams, Illustrator of American Childhood". The New Yorker. ISSN 0028-792X. Retrieved April 10, 2018.

- ^ Wilder, Laura Ingalls. The Little House Books. U.S.A. : Harper & Row Publishers Inc., 1971.

- ^ "The 100 Best Young-Adult Books of All Time". TIME.com. Retrieved April 11, 2018.

- ^ Bird, Elizabeth (July 7, 2012). "Top 100 Chapter Book Poll Results". A Fuse #8 Production Blog (blog.schoollibraryjournal.com). School Library Journal. Archived from the original on July 13, 2012. Retrieved October 31, 2015.

- ^ admin (November 30, 1999). "Newbery Medal and Honor Books, 1922-Present". Association for Library Service to Children (ALSC). Retrieved April 11, 2018.

- ^ Cannon, Brian Q. (2013). "Homesteading Remembered: A Sesquicentennial Perspective". Agricultural History. 87 (1): 1–29. doi:10.3098/ah.2013.87.1.1. JSTOR 10.3098/ah.2013.87.1.1.

- ^ Eschner, Kat. "The Little House on the Prairie Was Built on Native American Land". Smithsonian. Retrieved April 10, 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Smulders, Sharon (January 1, 2002). "'The Only Good Indian': History, Race, and Representation in Laura Ingalls Wilder's Little House on the Prairie". Children's Literature Review Quarterly. 27 (4): 191–202.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Fraser, Caroline (March 13, 2018). "Perspective | Yes, 'Little House on the Prairie' is racially insensitive — but we should still read it". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved April 10, 2018.

- ^ https://www.theguardian.com/books/2018/jun/24/laura-ingalls-wilders-name-removed-from-book-award-over-racial-concerns

- ^ admin (November 30, 1999). "Welcome to the (Laura Ingalls) Wilder Award home page!". Association for Library Service to Children (ALSC). Retrieved April 11, 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Tharp, Julie; Kleiman, Jeff (2000). ""Little House on the Prairie" and the Myth of Self-Reliance". Transformations: The Journal of Inclusive Scholarship and Pedagogy. 11 (1): 55–64. JSTOR 43587224.

- ^ Becker, Lawrence C. (1976). "The Labor Theory of Property Acquisition". The Journal of Philosophy. 73 (18): 653–664. doi:10.2307/2025823. JSTOR 2025823.

- ^ "Martha and Charlotte - Melissa Wiley". Melissa Wiley. Retrieved April 11, 2018.

- ^ "Little House: The Caroline Years Series by Maria D. Wilkes". www.goodreads.com. Retrieved April 11, 2018.

- ^ "Little House: The Rose Years Series by Roger Lea MacBride". www.goodreads.com. Retrieved April 11, 2018.

- ^ Wilder, Laura Ingalls (1974). West from Home. New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 978-0-06-440081-7.

- ^ Wilder, Laura Ingalls (1962). On the Way Home. New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 978-0-06-440080-0.

- ^ Anderson, Laura Ingalls Wilder: The Iowa Story, pp. 1–2.

- ^ Gormley, Laura Ingalls Wilder: Young Pioneer, p. 36.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Wilder, Laura Ingalls (1932). Little House in the Big Woods. New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 0-06-440003-4.

- ^ Wilder, Laura Ingalls (1933). Farmer Boy. New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 0-06-440002-6.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Wilder, Laura Ingalls (1935). Little House on the Prairie. New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 0-06-440004-2.

- ^ "The Herbert Hoover Presidential Library and Museum". archives.gov. Archived from the original on October 25, 2014. Retrieved October 25, 2014.

- ^ Wilder, Laura Ingalls (1937). On the Banks of Plum Creek. New York: Harper & Row.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g Wilder, Laura Ingalls (1939). On the Shores of Silver Lake. New York: Harper & Row.

- ^ Laskin, David. The Children's Blizzard. New York: HarperCollins, 2004. Pp. 56–57.

- ^ Potter, Constance. "Genealogy Notes: De Smet, Dakota Territory, Little Town in the National Archives, Part 2". Prologue, Vol. 35, No. 4 (Winter 2003).

- ^ Robinson, Doane. History of South Dakota (1904). Volume I, Chapter III, pp. 306–09.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Wilder, Laura Ingalls (1940). The Long Winter. New York: Harper & Row.

- ^ Kuznets, Lois R. (Spring 2000). "Wild and Wilder: Gendered Spaces in Narratives for Children and Adults". Michigan Quarterly Review. XXXIX (2). hdl:2027/spo.act2080.0039.226. ISSN 1558-7266.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Wilder, Laura Ingalls (1941). Little Town on the Prairie. New York: harper & Row.

- ^ "These happy golden years" (first edition). Library of Congress Online Catalog (catalog.loc.gov). Retrieved September 17, 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h Wilder, Laura Ingalls (1943). These Happy Golden Years. New York: Harper & Row.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Wilder, Laura Ingalls (1971). The First Four Years. New York: Harper & Row.

- ^ "Little House on the Prairie". littlehouseontheprairie.com.

- ^ Cole, Marcus (January 2, 2000), Beyond the Prairie: The True Story of Laura Ingalls Wilder, Rob Halverson, Terra Allen, Alandra Bingham, retrieved April 11, 2018

- ^ "The Television Mini-Series". littlehouseontheprairie.com.

- ^ Gans, Andrew. "New Musical Little House on the Prairie Makes World Premiere July 26 at the Guthrie" Archived July 29, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, playbill.com, July 26, 2008

- ^ Rothstein, Mervyn."Prairie Tales" Archived July 29, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, playbill.com, July 26, 2008

- ^ "The Legacy of Laura Ingalls Wilder - a Documentary DVD". littlehouseontheprairie.com. Retrieved April 11, 2018.

Further reading[]

- Fraser, Caroline (2017). Prairie Fires. New York: Metropolitan Books. ISBN 978-1-62779-276-9.

- Fraser, Caroline (March 13, 2018). "Yes, 'Little House on the Prairie' is racially insensitive — but we should still read it". The Washington Post. Washington D.C.

- Kilgore, John. "Little House in the Culture Wars". Eastern Illinois University. Retrieved May 13, 2008.

- Limerick, Patricia Nelson (November 20, 2017). "'Little House on the Prairie' and the Truth About the American West". The New York Times. New York, NY.

- Miller, John E. (May 1998). Becoming Laura Ingalls Wilder: The Woman Behind the Legend. University of Missouri Press. ISBN 978-0-8262-1167-5.

- Russo, Maria (February 7, 2017). "Finding America, Both Red and Blue in the 'Little House' Books". The New York Times. New York, NY.

- Smulders, Sharon (2003). "'The Only Good Indian': History, Race, and Representation in Laura Ingalls Wilder's Little House on the Prairie'". Children's Literature Association Quarterly. 27 (4).

- Tharp, Julie; Kleiman, Jeff (Spring 2000). "Little House on the Prairie and the Myth of Self Reliance". Transformations: The Journal of Inclusive Scholarship and Pedagogy. 11 (1, 10TH ANNIVERSARY ISSUE): 55–64. JSTOR 43587224.

- Zochert, Donald (May 1, 1977). Laura: The Life of Laura Ingalls Wilder. Avon. ISBN 978-0-380-01636-5.

External links[]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Little House on the Prairie |

, including the complete text of the first eight Little House books

- Little House On The Prairie

- Little House Books

- Little House on the Prairie historic site, near Independence, Kansas

- Little House series

- American children's book series

- Book series introduced in 1932

- Harper & Brothers books