Living street

This article has multiple issues. Please help or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

A living street is a street designed in the interests of pedestrians and cyclists. Living streets also act as social spaces, allowing children to play and encouraging social interactions on a human scale, safely and legally. These roads are still available for use by motor vehicles, however their design aims to reduce both the speed and dominance of motorised transport. This is often achieved using the shared space approach, with greatly reduced demarcations between vehicle traffic and pedestrians. Vehicle parking may also be restricted to designated bays. These street design principles first became popularized in the Netherlands during the 1970s, and the Dutch word woonerf (lit. residential grounds) is often used as a synonym for living street.

Overview[]

Current street infrastructure in the US[]

The U.S. Department of Transportation's Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices focuses primarily on vehicular traffic and how to optimize its movement.[1] Conversely, the concept of a living street focuses on creating healthier, more walkable, and more livable places while optimizing environmental benefits.[1] Living streets aim to prioritize the safety of all street users, especially more vulnerable groups such as pedestrians and cyclists, by improving infrastructure to accommodate all street users.

Urban Design Professor Donald Appleyard's Street Livability Study in the 1970s suggested streets in the United States were often noisy, polluted, and dangerous, and residents and cities both do not feel in control of creating clean and safe street environments.[2] Livable streets aim to create cleaner and safer environments[3] by "greening"[further explanation needed] streets and creating spaces where cars are guests to pedestrians and cyclists. This concept prioritizes the environment and the community over accessibility and movement of traffic. The Dutch woonerf is an example of this concept: it eliminates exclusive spaces for pedestrians and vehicular traffic, instead encouraging the whole street to be accessible to pedestrians and providing traffic calming measures for vehicles.[4] In their paper Reclaiming the Residential Street as a Play Place, Trantle and Doyle argue that woonerfs increase traffic safety and children are more likely to play near or in the street.[5]

Purpose of the living street[]

The living street reimagines the role of the street by reconsidering its purpose and who it is intended to serve. When implemented, the street may be a cooler, safer, more walkable, more attractive place that promotes the user's health and wellbeing.[6] It can serve as a recreational space for the neighborhood and improve the air quality through reduced carbon emissions and other air pollutants as well as improve water quantity and quality. Living streets can also prevent erosion and flooding through storm water management and reuse.[7] It has three major components: being green, cool and complete.[8]

Street Concepts[]

Green streets[]

Green streets can help alleviate water security issues.[8] Green street design involves implementing stormwater management strategies to protect nearby water sources from pollutants, and encouraging water reuse. Managing water at the source reduces the amount of pollutants carried into local water supplies. Pollutants can be harmful to local ecosystems and water quality.[9] Such strategies include building planter boxes, which can absorb stormwater runoff with pollutants, and bioswales which can filter stormwater and recharge groundwater supplies.[10] Trees are another aspect of the green street design: they can reduce the effects of the urban heat island (see "Cool streets" below) since they shade paved surfaces from heat. They also use evaporative cooling and can sequester carbon, improving air quality and reducing carbon emissions.[11]

Cool streets[]

Cool streets aim to reduce the effects of the urban heat island (UHI). Traditional streets are made of dark impervious materials which absorb energy from the sun and create warmer surrounding temperatures which increase both emissions and stormwater temperatures.[12] Replacing these surfaces with lighter-colored materials lets the street surface reflect solar energy.[13] Consequently, the lower temperatures reduce both emissions, meaning communities may have fewer temperature-related illnesses, and the temperature of stormwater runoff, reducing its impact on aquatic life in receiving waters.[14] These lighter surfaces are also more resistant to heat degradation and their reflective properties allow for more visibility at night.[8]

Complete streets[]

Complete streets are intended to be accessible, accommodating, and safe for pedestrians and cyclists by implementing strategies to promote active travel. They are intended to provide social equity for all users. Factors such as trip duration, path gradation, and typical weather conditions are assessed to see if active travel is possible.[8] Design strategies in complete streets include raised crosswalks - a traffic calming device that brings motor traffic to the level pedestrians walk at - and curb extensions which increase space for street amenities such as plants, benches, and trees.[15]

History[]

Progress in the United States[]

Since the late 19th century American planners have faced problems concerning traffic congestion and street safety. The two typical designs of American neighborhoods were the gridiron plan and curvilinear street, but safety concerns regarding motor vehicles brought new street patterns in the 1920s, one being the "neighborhood unit." The Radburn plan developed by Henry Wright and Clarence Stein in the late 1920s as well as Clarence Perry's proposal in 1933 used the "neighborhood unit" to try to encourage prevention of traffic on residential streets.[16]

In the 1930s and 1940s, increased highway traffic provoked the publication of the Community Builders Handbook. Written by the Federal Housing Administration, the handbook provided a hierarchy of street types such as arterial, collector and minor access.[16] However, unsafe conditions were still being observed, and street types were not meeting their intent.[17] Following this, cul de sacs and diverters were used in places such as Montclair and Grand Rapids to encourage streets to fulfill their assigned street type.[16] In the 1950s and 1960s, extensive urban development projects concerning housing and highway construction brought increased volumes of traffic and improvements focused on the flow of the motorized vehicle.[16] Colin Buchanan's Traffic in Towns published in 1963 in England introduced his American companions to the concept of "environmental areas", places where pedestrians are safe from motorized vehicles.[16] He acknowledged that there was an environmental capacity to every street, and pedestrian safety, air and noise pollution, and lighting were all of particular concern. This report influenced design in countries such as Sweden and Australia as well as San Francisco's Urban Design Plan.[2]

At the national level, the Federal Highway Administration sponsored a study conducted by Donald Appleyard in the 1970s looking at the impacts of traffic on residential streets.[18] From the study (which looked at 500 homes in the San Francisco area in comparison to other international street designs) they found that residents were deterred by the unsafe travel speeds of motorized vehicles.[18] This was a particular concern in areas with child and elderly populations. Noise and pollution decreased the overall livability of the streets, while more social interaction and perceived privacy was found on streets with lower traffic volumes. Stress, occupancy turnover, and adapting to unsafe living conditions were also results of unfavorable traffic conditions.[18] The findings of Appleyard's Street Livability Study inspired the San Francisco City Planning Board to launch the San Francisco Urban Design Plan in 1971 which introduced the idea of the "protected residential area."[19] The goal of the design was to slow down traffic to acceptable speeds in residential areas through infrastructure improvements for active transport as well as traffic calming measures. While the city's focus in street design used to be increasing the flow of motor traffic, this new approach discouraged high travel speeds. Following this plan, San Francisco developed the Protected Residential Area Program (PRA) which allowed neighborhoods to petition for traffic management measures. This encouraged community participation as well as equity and safety for all residents.[16]

Influence from other countries[]

Dutch, Danish, and German cities have incorporated several design concepts and policies surrounding traffic management. They have seen improvements in overall street safety and for the more vulnerable modes of transport such as walking and cycling. The focus on active transport in countries like the Netherlands may be attributed to the more car restrictive policies they have had in place since the 1970s.[20] The woonerf, home zone and require motorists to drive at walking speeds and yield to pedestrians, cyclists, and playing children who have the same rights in road use.[21]

These cities have implemented traffic calming measures, have dedicated auto-free zones for pedestrians and cyclists, enforce lower travel speeds, and have limited and more expensive parking compared to the United States. They have no turn on red, a concept the United States has had since the 1970s which has led to a drastic increase in pedestrian and cyclist injuries.[22] Street design in the United States tends to focus more on travel speed of motorized vehicles. In these European countries, the mindset is that motorists should anticipate the actions of pedestrians and cyclists. Their traffic calming measures have had a significant impact on traffic accidents: Dutch neighborhoods have seen traffic accidents reduced by up to 70% in some areas,[23] whereas a study looking at Denmark, the United Kingdom and the Netherlands found that traffic-related injuries in traffic calming neighborhoods fell by about 53%.[24]

These studies and ideas have changed some of the mindsets and ideas of street planning and design in the United States. Some planners and designs in the United States now see the street as a place to live, gather, and play instead of a means to get from one place to another. They have started to address how to make streets clean and safe for everyone, and a place where the community can gather and socialize.[16]

Some cities in the US such as Portland and Minneapolis have increased cycling rates over five-fold from 1990 to 2008 through the implementation of the same practices used in Europe, such as improved cycling infrastructure, public education on traffic safety, integration with public transportation, increased bike sharing, and traffic calming measures.[25] These cities have found that even though the United States has a history and culture associated with using motorized vehicles as a means of commuting, policies and infrastructure can influence people's actions and habits.[26]

Post-COVID city[]

The COVID-19 pandemic gave birth to proposals for radical change in the organisation of the city, such as the Manifesto for the Reorganisation of the City after COVID19 published in Barcelona, signed by 160 academics and 300 architects. The pedestrianisation of the whole city, a transportation based on the bicycle and an efficient public transport and the inversion of the concept of sidewalk are some of the Manifesto's key elements.[27][28][29]

Design[]

The design of the living street aims to restrict car use and parking by reducing convenience to motor vehicles while promoting safe walking and cycling. This is accomplished through better infrastructure, traffic calming, integration of walking and cycling with public transport, policies that encourage mixed-use development, regulations that are sensitive to more vulnerable populations and commuters, and traffic education for communities. Proponents believe a successful design cannot simply be individual measures taken but a combined, comprehensive approach that implements all these factors into a fully integrated and incorporated design.[30]

Environmental Design[]

Street trees shade surfaces and provide protection from the sun. This can lead to a longer life of the infrastructure, which saves in replacement costs and turnover for the surfaces. They can also reduce surrounding temperatures and improve air quality.[31] Stormwater management is another strategy, that includes permeable paving and bioretention planters and swales. Permeable pavement can be used for sidewalks, bike lanes, parking lanes, and low-volume streets to allow water to infiltrate through surfaces and reduce runoff to nearby water.[32] Bioretention planters and swales are typically used in planting strips or curb bulb outs to treat storm water runoff. Swales can be used where the water can infiltrate the soil, whereas planters should be used when infiltration into the existing soil is not desired.[33][34]

Traffic Calming Measures[]

In order to reclaim streets as a play area for children and a place for the community to gather and socialize, traffic calming measures can be put in place. This may include introducing speed bumps, changing the surface of the road, or creating artificial chicanes. These measures physically enforce reasonable speeds, rather than signage which can have little effect on the driver's actions - instead, drivers are forced to be more aware of their actions and the actions of other street users.[35] Other traffic calming measures include raised intersections and pedestrian crossings which bring the vehicles to the pedestrian level, indicating cars do not have full ownership of the road and must be vigilant of other road users. Chicanes, narrower travel lanes, and roundabouts purposefully slow down cars to safer speeds. Extensive car-free areas, wide, well-lit sidewalks, refuge islands for crossings, crossing signals, and zebra crossings provide safe and convenient facilities for more vulnerable road users. The woonerf in the Netherlands incorporates some of these traffic calming techniques but goes further in that it uses the concept of the shared street where separate spaces are not defined and pedestrians have access to the entire street. Developing the street more by filling in the "street wall" is another design measure to encourage walking and cycling. This concept consists of filling in the empty spaces and large parking lots often found adjacent to streets to make the street not only more attractive or inviting but also more accessible to these active commuters.[36] In addition, moving parking lots to the back of the store like found in European countries gives priority to pedestrians and cyclists near the entrance.[21]

Living streets focus on how to best move people and not just the car. The design aims resolve issues such as high-speed traffic arterials, too few intersections, and lack of sidewalks.[36] There may be dedicated transit lanes, sidewalks and bike lanes, and spaces that serve the entire community regardless of age, income, or ability. Measures such as bike lanes and safe, accessible maintained sidewalks will provide the infrastructure for the community to become active commuters.[8] Further design strategies such as medians can serve as a safety net for pedestrians and indicate pedestrian presence for motor vehicles, while reducing lane and land width and bulb-outs can decrease a pedestrian's crossing distance. Speed bumps and traffic circles can make the street seem like less of a highway.[8] Instead, these measures encourage lower travel speeds and therefore bring increased safety for other street users. Adequate signage, signals, and lighting can also be used to make all users aware the street is a shared space.[8] These measures may require even less space to carry more people.[36]

Compact and Mixed Use Development[]

Compact and mixed-use development is another strategy of the living street since how land is used will determine trip distances and preferred modes of transportation. Cycling is typically done at distances below 3 km and walking is typically done at distances below 1 km.[21] If trip destinations are within walking or cycling distance, people may utilize the sidewalks and bike lanes for their commute. In addition, compact neighborhoods will also make transit a realistic option because the population will exist to provide the necessary ridership.[36] Advocates suggest establishing strong neighborhood centers with local accessibility - instead of creating separate commercial and residential areas, which promote car use through increased trip lengths – that will lead to more sustainable and livable conditions.[37]

Benefits[]

Living streets are sustainable from an economical, environmental, and social view. They can promote public health through the different modes of active transport offered as well as social equity through enhancing livability for all users. The design is intended to reduce traffic danger and increase safety using modes of active transport that have minimal noise and air pollution and use far fewer non-renewable resources compared to motorized transportation. By reducing the number of cars and incorporating public and active transport, living streets can move more people with the same or less amount of space than the current street since these modes take up far less space than cars, whether in use or in storage.[38]

Health[]

The design of living streets makes it easier for people to satisfy the need for daily physical activity since they can walk or cycle as a part of their commute. Walking and cycling provides a form of physical activity and accounts for numerous health benefits that can combat current concerns for public health. In comparing obesity rates with walking and cycling for commuters between countries, studies show that the countries with a greater number of cyclist and pedestrian commuters tend to have lower rates of obesity.[39] Lack of exercise can also lead to other chronic health problems like diabetes or heart disease. In addition, walking and cycling can reduce the number of cars on the street, bringing a reduction in air, water and noise pollution as well as carbon emissions. This cleaner air may also reduce asthma and other respiratory diseases in urban areas.[40] The CLAN study conducted by Carver and Crawford in 2008 revealed that the built environment and street design can also play a role in the health and wellbeing of children.[41]

Safety[]

Government injury rate statistics from Californian cities and European countries show that higher numbers of cycling and walking may increase safety. Public health consultants such as Peter Jacobsen suggest this is because there is a greater awareness of cyclist and pedestrian movements so motor vehicles are more prepared to react and avoid accidents.[42] In addition, motorists may also be cyclists or pedestrians themselves which makes them more sensitive to the needs and rights of these more vulnerable groups.[21] Larger groups of these active commuters may also justify more rights to the road and an increase in improving and enhancing public infrastructure geared toward them. Fewer cars can also reduce traffic congestion.

Social[]

Living streets give more options for how people travel or get from one place to another and balances options so it is safe for all users. In addition, revitalizing existing areas instead of continuing suburban sprawl helps utilize and build upon past investments in infrastructure. This revitalization may include improved infrastructure that encourages people to sit, walk, and gather instead of being driven away by noisy traffic polluting the air. In addition, more people out and about in the streets can help reduce crime.[36]

The concept of living streets also works to prevent alienation children may have with their surroundings by providing them spaces to play and develop in an outdoor environment. The spaces allow children to experience different environments and communities as well as the ability to develop new relationships with others in these safer spaces.[43] As a result, children living near these streets will be healthier individuals since they have a greater and safer exposure to the environment around them and are able to develop relationships and interact with various individuals.[44]

Equity[]

Living street designs are intended to serve all users. The concept hopes to advance livability for the entire community by envisioning the street as providing multiple benefits for several types of users instead of simply a means for motorized traffic to get from one place to another. This investment in public infrastructure also seeks to provide more economical alternatives for the user since they do not need a car to get from place to place.

Instead of focusing solely on the movement of cars, living streets are designed to move people and focus more broadly on several different modes of transportation that can be accessible to all people.[45] A significant deterrent to active transport is a lack of traffic safety, especially to groups of society like the elderly and children who are more vulnerable to these dangers and, with current streets, often need more protection from car traffic.[46] Increased walking and cycling in these groups would improve their physical activity and expand their mobility and independence.

In addition, current streets may have uninviting landscapes or be unsafe to walk or bike on, meaning driving a car is often the only safe or practical option. There is no place to gather or congregate or for children to play, and it is hard for the more vulnerable groups like children and those with disabilities to travel in anything but the car.[47] Since lower income or senior citizens may not be able to afford or operate cars and rely on other modes of transportation to move around and be independent, living streets provide more economical and independent modes of transport. In addition, implementation of street trees, foundations, and plazas can allow people to gather and enjoy the street in a shared and communal experience.

Counterarguments[]

Opponents to the living street believe that if more people opt for active transport alternatives as opposed to utilizing motor vehicles, travel time will increase significantly and will be inconvenient for commuters. They also believe that unless people utilize the infrastructure for active transport the living street provides, other nearby non-living streets will be congested due to the hindrance the living street creates for the motor vehicle.[48]

Chicago Reader writer John Greenfield questions whether improving active transport infrastructure and encouraging transit-oriented development in communities will only increase property values, taxes, and rent, resulting in 'environmental gentrification' as marginalized groups are pushed out of their newly improved communities.[49] Chicago leader Amara Enyia suggests that while the concept focuses on decreasing dangerous driving, another result has been unfair enforcement of bike ticketing targeted at communities with people of color.[49]

In 2020, the Institute for Housing Studies at DePaul University used their Mapping Displacement Pressure in Chicago tool to find that the addition of the 606 linear park system in Chicago significantly increased prices in the more affordable adjacent neighborhoods, indicating the vulnerability of marginalized groups in new and sustainable public infrastructure.[50]

Around the world[]

| Country | Local name | Maximum Speed (km/h) | Details | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | Shared zone | 10 | ||

| Bike boulevard | 30 | Described by the Department of Transport (Western Australia) as "an innovative program designed to make cycling safer and easier". Bike boulevards are marked with blue-and-white Safe Active Street road patches at major entry points.[51] | ||

| Austria | ("Living street") |

Similar legislation as in Germany | ||

| Belgium | Woonerf, erf[52] (Dutch) Zone résidentielle, zone de rencontre[53] (French) |

20 | Usually same grade, parking is only allowed in marked places. | |

| Canada | Woonerf | Woonerfs are planned for Toronto,[54] where they have been approved for the West Don Lands community and are being discussed for Queens Quay along the waterfront, Honest Ed's redevelopment in Mirvish Village and for Montreal,[55] where one will replace an alley covering the former course of the St-Pierre river in Saint-Henri. | ||

| Czech Republic | ("Residential street") | 20 | Usually same grade, parking is only allowed in marked places. | In Czech law since 2001 |

| Finland | Pihakatu ("Yard street") |

20 | Pedestrians have absolute right of way. Parking is only allowed for bicycles and mopeds or in marked places. | The first living street was introduced in 1982 in Forssa. |

| France | ("Encounter zone") |

20 | Usually same grade, parking restrictions not specified | The first living street was introduced in 2008. |

| Germany | ("Traffic calming area") |

6 | Vehicles should not travel faster than a pedestrian speed. If not same grade then street usable by pedestrians. Parking is only allowed in marked places. Pedestrians, including children, may use the entire street and children are permitted to play in the street

In everyday language, a Verkehrsberuhigter Bereich is also called a Spielstraße ("play street"). |

Under German traffic law motorists in a Verkehrsberuhigter Bereich are restricted to a maximum speed of 7 km/h.[56] |

| Italy | Zona 30 | 30 | Vehicles should not travel faster than 30 km/h without interfering with pedestrians or cyclists. Both beginnings and endings of living streets are marked. | Introduced by the legislation on traffic in 1995. Actually it is seldom fully implemented like in the original Dutch model; very often a "Zona 30" is only indicated by a street sign and the speed limit. |

| Netherlands | Woonerf | 15 | Usually same grade | |

| New Zealand | Shared zone | Similar to Australia | ||

| Norway | Gatetun ("Courtyards") | 15 | ||

| Poland | Strefa zamieszkania ("Residential zone") |

20 | Pedestrians (including playing children, even without parental supervision) can use entire street and have absolute precedence over vehicles. Parking is only allowed in marked places. Speed calming devices do not have to be marked using road signs. The sign that marks an end of a living street also obligates a driver to give way to other participants in road traffic[57] | |

| Russia | ("Living zone") |

20 | No through traffic or parking with engine running. | |

| Serbia | Zona usporenog saobraćaja ("Decelerated-traffic zone") | 10 | Vehicles should not travel faster than a pedestrian speed and without interfering with pedestrians or cyclists. Both beginnings and endings of living streets are marked.[58] | Introduced by the legislation change in 2009, with first living streets introduced in September 2010.[59] |

| Slovakia | ("Residential street") | 20 | Usually same grade, parking is only allowed in marked places. | |

| Spain | Calle residencial ("Residential street") | 20 | Pedestrians (including playing children, even without parental supervision) can use entire street and have full right of way, however, the pedestrian shall not prevent a vehicle passing through. No parking except in marked places. Both beginnings and endings of living streets are marked. | |

| Sweden | Gångfartsområde ("Walking speed area") | 7 | Applies to both motorized vehicles and bikes. Pedestrians have absolute right of way. No parking, except in marked places. | |

| Switzerland | Zone de rencontre (French: "Encounter zone"), Begegnungszone (German: "Encounter zone") |

20 | Usually same grade. Parking is only allowed in marked places. | Introduced by the legislation change in September 2001. Link: Zones de rencontre |

| Turkey | Yaya öncelikli yol ("Pedestrian priority road") | 20 | Pedestrians (including playing children, even without parental supervision) can use entire street and have full right of way, however, the pedestrian shall not prevent a vehicle passing through. No parking except in marked places. Both beginnings and endings of living streets are marked. | |

| United Kingdom | Home zone, Living street |

Link: Signing | ||

| United States | Woonerf |

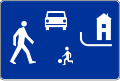

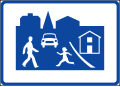

Street signs[]

Austria

Belgium

Czech Republic

Finland

Germany

Netherlands

Poland

Russia

Serbia

Slovakia

Spain

Sweden

Switzerland

See also[]

- Automotive city – Urban planning prioritising automobiles

- Bicycle-friendly – Urban planning prioritising cycling

- Carfree city – Urban area absent of cars

- List of car-free places

- Pedestrian zone – Urban car-free area reserved for pedestrian use

- Pedestrian village – Urban planning for mixed-use areas prioritising pedestrians

- Traffic conflict

- Transport divide – Unequal access to transport

- Urban vitality

- World Urbanism Day

References[]

- ^ a b "Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices for Streets and Highway". U.S Department of Transportation. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- ^ a b Appleyard, Donald (1980). "Livable Streets: Protected Neighborhoods?" (PDF). The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 451: 106–117. doi:10.1177/000271628045100111. JSTOR 1043165. S2CID 143106995. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- ^ "The complex ingredients of Livable Cities". Livable Streets. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- ^ "The Woonerf Concept" (PDF). NACTO. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- ^ "Reclaiming the Residential Street as a Play Space". ResearchGate. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- ^ "The Benefits of Street-Scale Features for Walking and Biking" (PDF). American Planning Association. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- ^ "Green Infrastructure: How to Manage Water in a Sustainable Way". NRDC. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Living Streets: A Guide for Los Angeles" (PDF). JSTOR. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- ^ "Ecosystems and Air Quality". EPA. 5 March 2014. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- ^ "Different Shades of Green" (PDF). EPA. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- ^ "Using Trees and Vegetation to Reduce Heat Islands". EPA. 17 June 2014. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- ^ "Heat Island Impacts". US EPA. 17 June 2014.

- ^ "Lighter coloured roads could reduce temperatures in hot urban areas" (PDF). Science for Environment Policy. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- ^ "Using Cool Pavements to Reduce Heat Islands". EPA. 17 June 2014. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- ^ "Urban Street Design Guide". NACTO. 11 July 2013. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Traffic in Urban American Neighborhoods" (PDF). JSTOR. JSTOR 23284803. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- ^ Distel, Marshall (January 2015). "Connectivity, Sprawl, and the Cul-de-sac: An Analysis of Cul-de-sacs and Dead-end Streets in Burlington and the Surrounding Suburbs". Uvm College of Arts and Sciences College Honors Theses. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- ^ a b c Livable Urban Streets: Managing Auto Traffic in Neighborhoods. Babel. Dot-Fh-11-8026. 1976. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- ^ "The Urban Design Plan". San Francisco Department of City Planning. 1971. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- ^ "Walking and Cycling in Western Europe and the United States" (PDF). Making Way for Pedestrians and Cyclists. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- ^ a b c d Pucher, John; Buehler, Ralph (2010). "Walking and Cycling for Healthy Cities" (PDF). Built Environment. 36 (4): 391–414. doi:10.2148/benv.36.4.391. JSTOR 23289966. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- ^ "It's Time for Cities to Rethink Right Turns on Red". StreetsBlog USA. 15 May 2018. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- ^ "Safe Aspects of Urban Infrastructure" (PDF). SWOV Institute for Road Safety Research, The Netherlands. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- ^ Hass-Klau, Carmen (1990). The Pedestrian and City Traffic. The National Academies of Sciences Engineering Medicine. ISBN 9781852931216. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- ^ "Portland Bicycle Plan for 2030". The City of Portland Oregon. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- ^ Mattioli, Giulio; Roberts, Cameron; Steinberger, Julia K.; Brown, Andrew (2020). "The political economy of car dependence: A systems of provision approach". Energy Research & Social Science. 66: 101486. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2020.101486. S2CID 216186279. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- ^ Paolini, Massimo (2020-04-20). "Manifesto for the Reorganisation of the City after COVID19". Retrieved 2021-05-01.

- ^ Argemí, Anna (2020-05-08). "Por una Barcelona menos mercantilizada y más humana" (in Spanish). Retrieved 2021-05-11.

- ^ Maiztegui, Belén (2020-06-18). "Manifiesto por la reorganización de la ciudad tras el COVID-19" (in Spanish). Retrieved 2021-05-11.

- ^ "Complete Streets: Best Policy and Implementation Practices" (PDF). American Planning Association. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- ^ "Urban Street Trees" (PDF). Walkable. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- ^ "Permeable Pavement". NACTO. 29 June 2017. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- ^ "Biofiltration Planter". NACTO. 29 June 2017. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- ^ "Bioretention Swale". NACTO. 29 June 2017. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- ^ a b c d e "Implementing Living Streets". JSTOR. 10 April 2014. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- ^ "Creating equitable, healthy, and sustainable communities" (PDF). EPA. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- ^ "On city streets, prioritize people over cars". The Fourth Regional Plan. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- ^ Pucher, John; Buehler, Ralph; Bassett, David R.; Dannenberg, Andrew L. (2010). "Walking and Cycling to Health: A Comparative Analysis of City, State, and International Data". American Journal of Public Health. 100 (10): 1986–1992. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2009.189324. PMC 2937005. PMID 20724675.

- ^ Guarnieri, M.; Balmes, J. R. (2014). "Outdoor air pollution and asthma". Lancet. 383 (9928): 1581–1592. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60617-6. PMC 4465283. PMID 24792855.

- ^ Carver, A.; Timperio, A. F.; Crawford, D. A. (2008). "Neighborhood Road Environments and Physical Activity Among Youth: The CLAN Study". Journal of Urban Health: Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. 85 (4): 532–544. doi:10.1007/s11524-008-9284-9. PMC 2443253. PMID 18437579.

- ^ Jacobsen, P. L. (2003). "Safety in numbers: more walkers and bicyclists, safer walking and bicycling". Injury Prevention. 9 (3): 205–209. doi:10.1136/ip.9.3.205. PMC 1731007. PMID 12966006. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- ^ Gabriel, Norman (2004). "Space Exploration: Developing Spaces for Children" (PDF). Geography. 89 (2): 180–182. JSTOR 40573962. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- ^ Donovan, Jenny (2016). "Enabling Play Friendly Spaces" (PDF). Environment Design Guide: 1–18. JSTOR 26152194. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- ^ "Complete Streets Mean Equitable Streets" (PDF). Smart Growth America. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- ^ "Prioritizing Transportation Equity through Complete Streets" (PDF). The University of Illinois at Chicago. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- ^ "Why inclusive cities start with safe streets". Curbed. 28 August 2019. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- ^ Guttenberg, Albert Z. (1982). "How to crowd and still be kind - The Dutch Woonerf" (PDF). Humboldt Journal of Social Relations. 9 (2): 100–119. JSTOR 23261950. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- ^ a b "Don't be a Livable Streets Jerk". Streetsblog Chicago. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- ^ "Mapping Displacement Pressure in Chicago, 2020". Institute for Housing Studies at DePaul University. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- ^ "Safe Active Streets Program". Department of Transport. Retrieved 19 October 2017.

- ^ "art.22bis". Justel-Dutch. 15 October 2019. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ^ "art.22bis". Justel-French. 15 October 2019. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ^ Hume, Christopher (2008-12-18). "Queens Quay future looks brighter than ever". The Star. Toronto. Retrieved 2010-03-27.

- ^ Heffez, Alanah (2011-05-01). "Saint-Pierre River Site to Become Montreal's first Woonerf". Spacing Montreal. Montreal. Retrieved 2011-06-08.

- ^ Right-of-way Brian's Guide to Getting Around Germany, Rules of the Road (Accessed 07/02/2007)

- ^ "Internetowy System Aktów Prawnych". Dz. U. 1997 nr 98 poz. 602 (with further changes - the unified text). Journal of Laws of the Republic of Poland (in Polish). 2012 [First published 1997]. Retrieved 2013-03-12.

- ^ "Zakon o bezbednosti saobraćaja na putevima". §161 (in Serbian). 2019 [First published 2009]. Retrieved 2019-09-10.

- ^ "Контрола кретања, заустављања и паркирања возила у зони успореног саобраћаја" (PDF) (in Serbian). 2010. Retrieved 2019-09-10.

External links[]

- Living streets A comprehensive list of names in different languages on the OpenStreetMap wiki

- Living streets in New Zealand

- A project example of landscape architecture [1]

- Living streets

- Types of streets

- Transportation planning

- Sustainable transport