Lolita (killer whale)

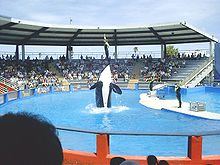

Lolita performing at Miami Seaquarium | |

| Species | Killer whale (Orcinus orca) |

|---|---|

| Breed | Southern resident |

| Sex | Female |

| Born | c. 1966 |

| Years active | 1970-present |

| Known for | Second oldest captive killer whale |

| Residence | Miami Seaquarium, Florida |

| Weight | 7,000 lb (3,200 kg)[1] |

| Named after | Lolita |

Lolita (born c. 1966), formerly known as Tokitae,[2] is an approximately 20 feet (6.1 m) long, 7,000 pound female orca who has lived at the Miami Seaquarium since September 24, 1970.[3] As of 2021, Lolita is the second oldest killer whale in captivity behind Corky at SeaWorld San Diego.[4] In 2017, a USDA audit found that Lolita's tank does not meet the legal size requirements per federal law.[5]

Life[]

Lolita is a member of the "L Pod" of Southern resident killer whales. She was captured from the wild on August 8, 1970 in Penn Cove, Puget Sound, Washington when she was approximately four years old. Lolita was one of seven young killer whales sold to oceanariums and marine mammal parks around the world from a capture of over eighty whales conducted by Ted Griffin and Don Goldsberry, partners in an operation known as Namu, Inc. The oldest known living Southern resident killer whale as of 2020, "L25 Ocean Sun", is speculated to be Lolita's mother and is estimated to be between eighty and ninety years old.[6][7]

Lolita was purchased by Miami Seaquarium veterinarian Dr. Jesse White for about $20,000.[8] Upon arrival to the Seaquarium, Lolita joined another Southern resident killer whale named Hugo who was also captured from Puget Sound and had lived in the park two years before her arrival. She was originally called "Tokitae," which "In Chinook jargon means, 'Bright day, pretty colors.'"[9] However, she was renamed Lolita after the heroine in Vladimir Nabokov's novel.[10]

The Lummi Nation of Washington State refer to Lolita as Sk’aliCh’elh-tenaut, or, a female orca from an ancestral site in the Penn Cove area of the Salish Sea bioregion. They view her as a member of their "qwe lhol mechen," which "'translates to ‘our relative under the water,’” according to former Lummi tribal chairman Jeremiah "Jay" Julius.[11][9]

She and Hugo lived together for ten years in what was then known as the "Whale Bowl",[12] a tank 80-by-35-foot (24 by 11 m) by 20 feet (6 m) deep.[13] The pair mated many times (once to the point of suspending shows[14]) but they never produced any offspring.[15] Hugo died on March 4, 1980, after a brain aneurysm occurred from the whale repeatedly ramming his head into the side of the tank. Thereafter, Lolita then shared the tank with a Short-beaked common dolphin and a Pilot whale during the 1980s and 1990s,[16] and today lives and performs with a pair of Pacific white-sided dolphins.[17]

Controversy[]

Animal rights groups and anti-captivity activists assert that Lolita is being subjected to cruelty.[13] In 2003, she was the subject of the documentary Lolita: Slave to Entertainment.[18][19] in which many anti-captivity activists, most notably Ric O'Barry (former Flipper dolphin trainer), argue against her current conditions and express a hope that she may be re-introduced to the wild.

On January 17, 2015, thousands of protesters from all over the world gathered outside the Miami Seaquarium to demand for Lolita's release and asked other supporters worldwide to tweet "#FreeLolita" on Twitter.[20]

In 2017, a USDA audit found that Lolita's tank does not meet the legal size requirements per federal law.[5]

In 2018 the Lummi Nation traveled to Seaquarium with a totem pole carved for Sk’aliCh’elh-tenaut, sang to her, and prayed that she would be returned to the Salish Sea Bioregion. According to journalist Lynda Mapes, "The Seaquarium would not allow tribal members any closer than the public sidewalk outside the facility where the whale performs twice a day for food."[11] Seaquarium Curator Emeritus Robert Rose responded to the Lummi's journey, saying that the Lummi Nation "should be ashamed of themselves, they don’t care about Lolita, they don’t care about her best interests, they don’t really care whether she lives or dies. To them, she is nothing more than a vehicle by which they promote their name, their political agenda, to obtain money and to gain media attention. Shame on them."[21] In response, environmental scholars and Julius have argued that such statements are representative of a troubling pattern of discounting Native American knowledge and relationships, theft, and possession, which are "part and parcel of the possessive nature of settler colonialism."[22]

On September 24, 2020, the 50th anniversary of Lolita's arrival at the Seaquarium, tribal members of the Lummi Nation, joined by the local Seminole, travelled to Miami again, held a ceremony in support of Sk’aliCh’elh-tenaut, and demanded she be released to her native waters.[4] The totem pole journey is currently ongoing.[23]

Some, such as the director of the University of British Columbia's Marine Mammal Research Unit, Andrew Trites, have argued that Lolita is too old for life in the wild and that reintroducing her to the ocean after over fifty years in captivity would be "unethical" and a "death sentence".[24] However, other environmental scholars have posited that such arguments are representative of colonial conservation policies, stating that "The whales were killed and captured one at a time by settlers. If they can be killed or captured one at a time, there is no reason why the whales cannot be helped one at a time. Individual whales and pods can be cared for. ‘Lolita’ can be returned to her home waters."[22]

Legal cases[]

In November 2011 Animal Legal Defense Fund (ALDF), PETA, and three individuals filed a lawsuit against the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) to end the exclusion of Lolita from the Endangered Species Act (ESA) of the Pacific Northwest's Southern resident killer whale. NMFS reviewed ALDF’s joint petition, along with the thousands of comments submitted by the public and found the petition merited.[25] In February 2015, the NOAA announced it would issue a rule to include Lolita in the endangered species list. Previous to this, although the killer whale population that she was taken from is listed as endangered, as a captive animal, Lolita was exempted from this classification. This change does not impact on her captivity at Miami Seaquarium.[26]

On March 18, 2014 a judge dismissed ALDF's case challenging Miami Seaquarium's Animal Welfare Act license to display captive killer whales.[27]

In June 2014 ALDF filed a notice of appeal of the District Court decision that found the USDA had not violated the law when it renewed Miami Seaquarium's AWA exhibitor license.[28]

See also[]

- List of captive orcas

References[]

- ^ Mapes, Lynda (June 17, 2019). "Remembering Lolita, an orca taken nearly 49 years ago and still in captivity at the Miami Seaquarium". Seattle Times. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- ^ "Lolita". orcanetwork.org. Orca Network. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- ^ "About Miami Seaquarium". Miami Seaquarium. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

- ^ a b McKenna, Cara 2020

- ^ a b Herrera, Chabeli (7 June 2016). "Lolita's tank at the Seaquarium may be too small after all, a new USDA audit finds". Miami Herald. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- ^ "Adopt L-25 Ocean Sun". whalemuseum.org. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- ^ "Lolita's Life Before Capture". orcanetwork.org. Orca Network.

- ^ Samuels, Robert (15 September 2010). "Lolita still thrives at Miami Seaquarium". seattletimes.nwsource.com. Seattle Times. Retrieved 9 August 2011.

- ^ a b Priest, Rena (2020). "A captive orca and a chance for our redemption". High Country News.

- ^ "Lolita officially named". The Miami News. November 30, 1970.

- ^ a b Mapes, Lynda (2018). "Lummi prayers, songs at Seaquarium just start of effort to free captive whale". Seattle Times.

- ^ Klinkenberg, Marty (15 December 1989). "KILLER WHALE COLD TO NEW TANKMATE". sun-sentinel.com. Sun-Sentinel. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- ^ a b "Lolita still thrives at Miami Seaquarium". Seattle Times. September 15, 2010.

- ^ "Sex Drive Stops Whale Show". The Palm Beach Post. December 4, 1977.

- ^ "Lolita: happy, gentle, smart; weighs 4 tons". Boca Raton News.

- ^ Klinkenberg, Marty 1989

- ^ Herrera, Chabeli (20 November 2017). "Lolita may never go free. And that could be what's best for her, scientists say". miamiherald.com. Miami Herald. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- ^ Lolita: Slave to Entertainment (2003) at IMDb

- ^ "Lolita: Slave to Entertainment". Houston Press. Retrieved 2021-03-16.

- ^ Rodriguez, Laura (17 January 2015). "Protesters March to Free Orca Lolita from Miami Seaquarium". nbcmiami.com. NBC Miami. Retrieved 17 January 2015.

- ^ Rose, Robert (2018). "Lolita Update From Our Curator Emeritus, Robert Rose". Facebook.

- ^ a b Guernsey, Paul J.; Keeler, Kyle; Julius, Jeremiah ‘Jay’ (2021-07-30). "How the Lummi Nation Revealed the Limits of Species and Habitats as Conservation Values in the Endangered Species Act: Healing as Indigenous Conservation". Ethics, Policy & Environment: 1–17. doi:10.1080/21550085.2021.1955605. ISSN 2155-0085.

- ^ Mapes, Lynda (2021). "Lummi Nation totem pole arrives in D.C. after journey to sacred lands across U.S." Seattle Times.

- ^ Pawson, Chad (28 May 2018). "B.C. marine mammal expert says moving killer whale from Miami a death sentence". cbc.ca. CBC.ca. Retrieved 22 April 2021.

- ^ "Make a Splash: Free Lolita!". ALDF. Archived from the original on 2014-11-12. Retrieved 2014-07-16.

- ^ "Captive killer whale included in endangered listing". NOAA. 4 February 2015.

- ^ "Sequarium Docket". March 18, 2014.

- ^ "Judge's Refusal to Review Seaquarium's Violations of Law Prompts Court Appeal". ALDF. Archived from the original on 2014-07-22. Retrieved 2014-07-16.

External links[]

- Individual killer whales

- Southern resident killer whales