Look-and-say sequence

In mathematics, the look-and-say sequence is the sequence of integers beginning as follows:

To generate a member of the sequence from the previous member, read off the digits of the previous member, counting the number of digits in groups of the same digit. For example:

- 1 is read off as "one 1" or 11.

- 11 is read off as "two 1s" or 21.

- 21 is read off as "one 2, then one 1" or 1211.

- 1211 is read off as "one 1, one 2, then two 1s" or 111221.

- 111221 is read off as "three 1s, two 2s, then one 1" or 312211.

The look-and-say sequence was introduced and analyzed by John Conway.[1]

The idea of the look-and-say sequence is similar to that of run-length encoding.

If started with any digit d from 0 to 9 then d will remain indefinitely as the last digit of the sequence. For any d other than 1, the sequence starts as follows:

- d, 1d, 111d, 311d, 13211d, 111312211d, 31131122211d, …

Ilan Vardi has called this sequence, starting with d = 3, the Conway sequence (sequence A006715 in the OEIS). (for d = 2, see OEIS: A006751)[2]

Basic properties[]

Growth[]

The sequence grows indefinitely. In fact, any variant defined by starting with a different integer seed number will (eventually) also grow indefinitely, except for the degenerate sequence: 22, 22, 22, 22, … (sequence A010861 in the OEIS)[3]

Digits presence limitation[]

No digits other than 1, 2, and 3 appear in the sequence, unless the seed number contains such a digit or a run of more than three of the same digit.[3]

Cosmological decay[]

Conway's cosmological theorem asserts that every sequence eventually splits ("decays") into a sequence of "atomic elements", which are finite subsequences that never again interact with their neighbors. There are 92 elements containing the digits 1, 2, and 3 only (92 is exactly the number of Johnson solids and exactly the number of non transuranium elements), which John Conway named after the chemical elements up to uranium, calling the sequence audioactive. There are also two "transuranic" elements for each digit other than 1, 2, and 3.[3][4]

Growth in length[]

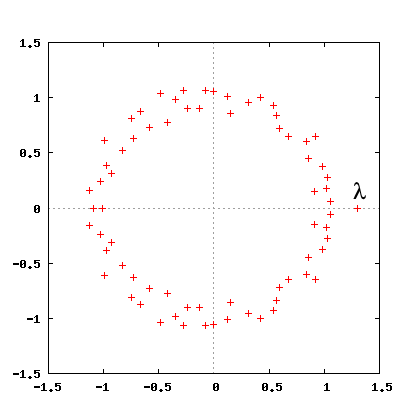

The terms eventually grow in length by about 30% per generation. In particular, if Ln denotes the number of digits of the n-th member of the sequence, then the limit of the ratio exists and is given by

where λ = 1.303577269034... (sequence A014715 in the OEIS) is an algebraic number of degree 71.[3] This fact was proven by Conway, and the constant λ is known as Conway's constant. The same result also holds for every variant of the sequence starting with any seed other than 22.

Conway's constant as a polynomial root[]

Conway's constant is the unique positive real root of the following polynomial: (sequence A137275 in the OEIS)

In his original article, Conway gives an incorrect value for this polynomial, writing − instead of + in front of .[5] However, the value of λ given in his article is correct.

Popularization[]

The look-and-say sequence is also popularly known as the Morris Number Sequence, after cryptographer Robert Morris, and the puzzle "What is the next number in the sequence 1, 11, 21, 1211, 111221?" is sometimes referred to as the Cuckoo's Egg, from a description of Morris in Clifford Stoll's book The Cuckoo's Egg.[6][7]

Variations[]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2012) |

There are many possible variations on the rule used to generate the look-and-say sequence. For example, to form the "pea pattern" one reads the previous term and counts all instances of each digit, listed in order of their first appearance, not just those occurring in a consecutive block. Thus, beginning with the seed 1, the pea pattern proceeds 1, 11 ("one 1"), 21 ("two 1s"), 1211 ("one 2 and one 1"), 3112 ("three 1s and one 2"), 132112 ("one 3, two 1s and one 2"), 311322 ("three 1s, one 3 and two 2s"), etc. This version of the pea pattern eventually forms a cycle with the two terms 23322114 and 32232114.[8]

Other versions of the pea pattern are also possible; for example, instead of reading the digits as they first appear, one could read them in ascending order instead. In this case, the term following 21 would be 1112 ("one 1, one 2") and the term following 3112 would be 211213 ("two 1s, one 2 and one 3").

These sequences differ in several notable ways from the look-and-say sequence. Notably, unlike the Conway sequences, a given term of the pea pattern does not uniquely define the preceding term. Moreover, for any seed the pea pattern produces terms of bounded length. This bound will not typically exceed 2 * radix + 2 digits and may only exceed 3 * radix digits in length for degenerate long initial seeds ("100 ones, etc"). For these maximum bounded cases, individual elements of the sequence take the form a0b1c2d3e4f5g6h7i8j9 for decimal where the letters here are placeholders for the digit counts from the preceding element of the sequence. Given that this sequence is infinite and the length is bounded, it must eventually repeat due to the pigeonhole principle. As a consequence, these sequences are always eventually periodic.

See also[]

References[]

- ^ Conway, John (January 1986). "The Weird and Wonderful Chemistry of Audioactive Decay". Eureka. 46: 5–16. Archived from the original on 2014-10-11.

- ^ Conway Sequence, MathWorld, accessed on line February 4, 2011.

- ^ a b c d Martin, Oscar (2006). "Look-and-Say Biochemistry: Exponential RNA and Multistranded DNA" (PDF). American Mathematical Monthly. Mathematical association of America. 113 (4): 289–307. doi:10.2307/27641915. ISSN 0002-9890. JSTOR 27641915. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-12-24. Retrieved January 6, 2010.

- ^ Ekhad, S. B., Zeilberger, D.: Proof of Conway's lost cosmological theorem, Electronic Research Announcements of the American Mathematical Society, August 21, 1997, Vol. 5, pp. 78–82. Retrieved July 4, 2011.

- ^ Ilan Vardi, Computational Recreation in Mathematica

- ^ Robert Morris Sequence

- ^ FAQ about Morris Number Sequence

- ^ "Ascending Pea Pattern generator". codegolf.stackexchange.com. Retrieved 2016-05-07.

External links[]

- Conway speaking about this sequence and telling that it took him some explanations to understand the sequence.

- Implementations in many programming languages on Rosetta Code

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Look and Say Sequence". MathWorld.

- Look and Say sequence generator p

- OEIS sequence A014715 (Decimal expansion of Conway's constant)

- A Derivation of Conway’s Degree-71 “Look-and-Say” Polynomial

- Base-dependent integer sequences

- Algebraic numbers

- Mathematical constants

- John Horton Conway