Looting

Looting is the act of stealing, or the taking of goods by force, in the midst of a military, political, or other social crisis, such as war,[1] natural disasters (where law and civil enforcement are temporarily ineffective),[2] or rioting.[3] The proceeds of all these activities can be described as booty, loot, plunder, spoils, or pillage [4][5]

During modern-day armed conflicts, pillaging is prohibited by international law, and constitutes a war crime.[6][7]

Looting by type[]

Looting after disasters[]

During a disaster, police and military forces are sometimes unable to prevent looting when they are overwhelmed by humanitarian or combat concerns, or cannot be summoned due to damaged communications infrastructure. Especially during natural disasters, many civilians may find themselves forced to take what does not belong to them in order to survive.[8] How to respond to this, and where the line between unnecessary "looting" and necessary "scavenging" lies, is often a dilemma for governments.[9][10] In other cases, looting may be tolerated or even encouraged by governments for political or other reasons, including religious, social or economic ones.

In armed conflict[]

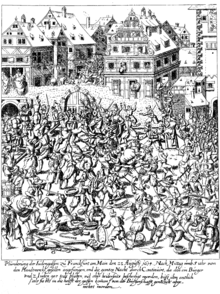

Looting by a victorious army during war has been common practice throughout recorded history.[11] Foot soldiers viewed plunder as a way to supplement an often meagre income[12] and transferred wealth became part of the celebration of victory. In the wake of the Napoleonic Wars, and in particular after World War II, norms against wartime plunder became widely accepted.[11]

In the upper ranks, the proud exhibition of the loot plundered formed an integral part of the typical Roman triumph, and Genghis Khan was not unusual in proclaiming that the greatest happiness was "to vanquish your enemies ... to rob them of their wealth".[13]

In warfare in ancient times, the spoils of war included the defeated populations, which were often enslaved. Women and children might become absorbed into the victorious country's population, as concubines, eunuchs and slaves.[14][15] In other pre-modern societies, objects made of precious metals were the preferred target of war looting, largely due to their ease of portability. In many cases looting offered an opportunity to obtain treasures that otherwise would not have been obtainable. Since the 18th century, works of art have increasingly become a popular target. In the 1930s, and even more so during the Second World War, Nazi Germany engaged in large-scale and organized looting of art and property, particularly in Nazi-occupied Poland.[16][17]

Looting, combined with poor military discipline, has occasionally been an army's downfall[citation needed] - troops who have dispersed to ransack an area may become vulnerable to counter-attack. In other cases, for example the Wahhabi sack of Karbala in 1801 or 1802, loot has contributed to further victories for an army.[18] Not all looters in wartime are conquerors; the looting of Vistula Land by the retreating Imperial Russian Army in 1915[19] was among the factors sapping the loyalty of Poles to the Russian Emperor. Local civilians can also take advantage of a breakdown of order to loot public and private property, as in events which took place at the National Museum of Iraq in the course of the Iraq War in 2003.[20] Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy's novel War and Peace describes widespread looting by Moscow's citizens before Napoleon's troops entered the city in 1812, along with looting by French troops elsewhere.

In 1990 and 1991, during the Gulf War, Saddam Hussein's soldiers caused significant damage to Kuwaiti and Saudi infrastructure. They also stole from private companies and homes.[21][22] In April 2003, looters broke into the National Museum of Iraq and thousands of artefacts remain missing.[23][24]

Syrian conservation sites and museums are looted during the Syrian civil war, with items being sold on the international black market.[25][26] Reports from 2012 suggested that these antiquities were being traded for weapons by the various combatants.[27][28]

Prohibited under international law[]

Both customary international law and international treaties prohibit pillage in armed conflict.[6] The Lieber Code, Brussels Declaration (1874), and Oxford Manual recognized the prohibition against pillage.[6] The Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907 (modified in 1954) obliges military forces not only to avoid the destruction of enemy property, but to provide protection to it.[29] Article 8 of the Statute of the International Criminal Court provides that in international warfare, the "pillaging a town or place, even when taken by assault" counts as a war crime.[6] In the aftermath of World War II, a number of war criminals were prosecuted[by whom?] for pillage. The International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (operative from 1993 to 2017) brought several prosecutions for pillage.[6]

The Fourth Geneva Convention of 1949 explicitly prohibits the looting of civilian property during wartime.[6][30]

Theoretically, to prevent such looting, unclaimed property is moved to the custody of the Custodian of Enemy Property, to be handled until returned to its owners.

Archaeological removals[]

The term "looting" is also sometimes used to refer to antiquities being removed from countries by unauthorized people, either domestic people breaking the law seeking monetary gain, or by foreign nations, which are usually more interested in prestige or previously, "scientific discovery". An example of this might be the removal of the contents of Egyptian tombs which were transported to museums across the West.[31] Whether this constitutes "looting" is a debated point, with other parties pointing out that the Europeans were usually given permission of some sort, and that many of the treasures wouldn't have been discovered at all if the Europeans hadn't funded and organized the expeditions or digs that located them. Many of these antiquities have already been returned to their country of origin voluntarily.

Looting of industry[]

In the aftermath of the Second World War, Soviet forces systematically plundered the Soviet occupation zone of Germany, including the Recovered Territories which were to be transferred to Poland. They sent valuable industrial equipment, infrastructure and whole factories to the Soviet Union.[32][33] The Allies, without rail transport and blocked by the seas, were limited to pillage of high value German scientific and industrial technologies such as rocketry and jet aircraft.

Many factories in the rebels' zone of Aleppo during the Syrian civil war were reported as being plundered and their assets transferred abroad.[34][35] Agricultural production and electronic power plants were also taken to be sold elsewhere.[36][37]

Wealth redistribution[]

In radical politics, the redistribution of income and wealth might include looting as a means to address wealth inequality.[38]

Gallery[]

Private security guards, barbed wire fencing, and boarded up windows to prevent looting of department stores in New York City during mass unrest in the United States, 7 June 2020

The Beit Ghazaleh Museum of Aleppo was looted of its contents prior to being hit by explosions (photo 2017)

General Dwight D. Eisenhower, Gen. Omar N. Bradley, and Lt. Gen. George S. Patton Jr., inspect art treasures stolen by Germans and hidden in salt mine in Germany (1945)

Looters attempting to enter a cycle shop in North London during the 2011 England riots

See also[]

- Arson

- Banditry

- Conflict resource

- Depredation

- Hijacking

- Looted art

- Piracy

- Prize of war

- Reparations for slavery in the United States

- Vandalism

- War crimes

Citations[]

- ^ "Baghdad protests over looting". BBC News. BBC. 2003-04-12. Retrieved 2010-10-22.

- ^ "World: Americas Looting frenzy in quake city". BBC News. 1999-01-28. Retrieved 2010-10-22.

- ^ "Argentine president resigns". BBC News. 2001-12-21. Retrieved 2010-10-22.

- ^ "the definition of looting". Dictionary.com. Retrieved 2016-12-12.

- ^ "Booty - Define Booty at Dictionary.com".

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Rule 52. Pillage is prohibited., Customary IHL Database, International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC)/Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Hague Convention on the Law and Customs of War on Land (Hague II), article 28.

- ^ Sawer, Philip Sherwell and Patrick (2010-01-16). "Haiti earthquake: looting and gun-fights break out". The Daily Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 2020-07-13.

- ^ "Indonesian food minister tolerates looting". BBC News. July 21, 1998. Retrieved May 11, 2010.

- ^ Jacob, Binu; Mawson, Anthony R.; Payton, Marinelle; Guignard, John C. (2008). "Disaster Mythology and Fact: Hurricane Katrina and Social Attachment". Public Health Reports. 123 (5): 555–566. doi:10.1177/003335490812300505. ISSN 0033-3549. PMC 2496928. PMID 18828410.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Sandholtz, Wayne (2008). "Dynamics of International Norm Change: Rules against Wartime Plunder". European Journal of International Relations. 14 (1): 101–131. doi:10.1177/1354066107087766. ISSN 1354-0661.

- ^ Hsi-sheng Chi, Warlord politics in China, 1916–1928, Stanford University Press, 1976, ISBN 0-8047-0894-0, str. 93

- ^ Henry Hoyle Howorth History of the Mongols from the 9th to the 19th Century: Part 1 the Mongols Proper and the Kalmyks, Cosimo Inc. 2008.

- ^ John K. Thorton, African Background in American Colonization, in The Cambridge economic history of the United States, Stanley L. Engerman, Robert E. Gallman (ed.), Cambridge University Press, 1996, ISBN 0-521-39442-2, p. 87. "African states waged war to acquire slaves [...] raids that appear to have been more concerned with obtaining loot (including slaves) than other objectives."

- ^ Sir John Bagot Glubb, The Empire of the Arabs, Hodder and Stoughton, 1963, p.283. "...thousand Christian captives formed part of the loot and were subsequently sold as slaves in the markets of Syria".

- ^ (in Polish) J. R. Kudelski, Tajemnice nazistowskiej grabieży polskich zbiorów sztuki, Warszawa 2004.

- ^ "Nazi loot claim 'compelling'". BBC News. October 2, 2002. Retrieved May 11, 2010.

- ^ Wayne H. Bowen, The History of Saudi Arabia, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2008, p. 73. ISBN 0-313-34012-9

- ^ (in Polish) Andrzej Garlicki, Z dziejów Drugiej Rzeczypospolitej, Wydawnictwa Szkolne i Pedagogiczne, 1986, ISBN 83-02-02245-4, p. 147

- ^ STEVEN LEE MYERS, Iraq Museum Reopens Six Years After Looting, New York Times, February 23, 2009

- ^ Kelly, Michael (1991-03-24). "The Rape and Rescue of Kuwaiti City". The New Republic. ISSN 0028-6583. Retrieved 2020-06-10.

- ^ "Oil Fires in Iraq". earthobservatory.nasa.gov. 2016-09-02. Retrieved 2020-06-10.

- ^ Barker, Craig. "Fifteen years after looting, thousands of artefacts are still missing from Iraq's national museum". The Conversation. Retrieved 2020-07-13.

- ^ Samuel, Sigal (2018-03-19). "It's Disturbingly Easy to Buy Iraq's Archeological Treasures". The Atlantic. Retrieved 2020-07-13.

- ^ Swann, Steve (2019-05-02). "'Loot-to-order' antiquities sold on Facebook". BBC News. Retrieved 2020-07-10.

- ^ Harkin, James. "The Race to Save Syria's Archaeological Treasures". Smithsonian. Retrieved 2020-07-10.

- ^ Baker, Aryn (2012-09-12). "Syria's Looted Past: How Ancient Artifacts Are Being Traded for Guns". Time. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved 2020-07-10.

- ^ Arbuthnott, Hala Jaber, Lebanon, and George. "Syrians loot Roman treasures to buy guns". The Times. ISSN 0140-0460. Retrieved 2020-07-10.

- ^ Barbara T. Hoffman, Art and Cultural Heritage: Law, Policy, and Practice, Cambridge University Press, 2006, p. 57. ISBN 0-521-85764-3

- ^ E. Lauterpacht, C. J. Greenwood, Marc Weller, The Kuwait Crisis: Basic Documents, Cambridge University Press, 1991, p. 154. ISBN 0-521-46308-4

- ^ "Egypt's Antiquities Chief Combines Passion, Clout to Protect Artifacts". National Geographic News. October 24, 2006.

- ^ "MIĘDZY MODERNIZACJĄ A MARNOTRAWSTWEM" (in Polish). Institute of National Remembrance. Archived from the original on 2005-03-21. See also other copy online Archived 2007-04-26 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "ARMIA CZERWONA NA DOLNYM ŚLĄSKU" (in Polish). Institute of National Remembrance. Archived from the original on 2005-03-21.

- ^ "Turkey looted Syria factory: Damascus - World News". Hürriyet Daily News. Retrieved 2020-07-10.

- ^ Webel, Charles; Tomass, Mark (2017-02-17). Assessing the War on Terror: Western and Middle Eastern Perspectives. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-315-46916-4.

- ^ Aljaleel, Alaa; Darke, Diana (2019-03-07). The Last Sanctuary in Aleppo: A remarkable true story of courage, hope and survival. Headline. ISBN 978-1-4722-6055-0.

- ^ Badcock, James (2019-01-14). "Turkey accused of plundering olive oil from Syria to sell in the EU". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 2020-07-13.

- ^ Osterweil, Vicky (2020). In Defense of Looting: A riotous history of uncivil action (First ed.). New York, NY. ISBN 978-1645036692.

General sources[]

- Abudu, Margaret, et al., "Black Ghetto Violence: A Case Study Inquiry into the Spatial Pattern of Four Los Angeles Riot Event-Types", 44 Social Problems 483 (1997)

- Curvin, Robert and Bruce Porter (1979), Blackout Looting

- Dynes, Russell & Enrico L. Quarantelli, "What Looting in Civil Disturbances Really Means", in Modern Criminals 177 (James F. Short Jr., ed., 1970)

- Green, Stuart P., "Looting, Law, and Lawlessness", 81 Tulane Law Review 1129 (2007)

- Mac Ginty, Roger, "Looting in the Context of Violent Conflict: A Conceptualisation and Typology", 25 Third World Quarterly 857 (2004). JSTOR 3993697.

- Stewart, James, "Corporate War Crimes: Prosecuting Pillage of Natural Resources", 2010

External links[]

Media related to Looting at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Looting at Wikimedia Commons

- Looting

- Property crimes