Lope de Rueda

show This article may be expanded with text translated from the corresponding article in Spanish. (July 2018) Click [show] for important translation instructions. |

Lope de Rueda | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 1510 |

| Died | 1565 |

| Nationality | Spanish |

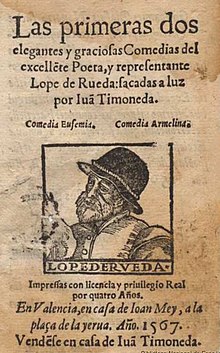

Lope de Rueda (c.1510–1565)[1] was a Spanish dramatist and author, regarded by some as the best of his era. A versatile writer, he also wrote comedies, farces, and pasos. He was the precursor to what is considered the golden age of Spanish literature.

His plays are considered a transitional stage between Torres Naharro and Lope de Vega.

Early life[]

He was born early in the sixteenth century in Seville, where, according to Cervantes, he worked as a metal-beater. His name first occurs in 1554 as acting at Benavente, taking mainly comic roles. Evnetually he got to be, between 1558 and 1561, manager of a strolling company which visited Segovia, Seville, Toledo, Madrid, Valencia and Córdoba. Cervantes, a child at the time, recalled having seen him and his company perform.

Works[]

His works were issued posthumously in 1567 by , who toned down certain passages in the texts.[1] de Rueda's more ambitious plays are mostly adapted from the Italian; in Eufemia he draws on Boccaccio,[2] in Medora he utilizes 's Zingara as well as Byzantine motives, in Arinelina he combines 's Attilia with 's Servigiale to create a satirical work ridiculing the superstitions current among Andalusians, and in Los Engañados (The Deceived) he uses Glingannati, a comedy produced by the Intronati, a literary society at Siena - itself ultimately derived from Plautus' Menaechmi. These follow the original so closely that they give no idea of de Rueda's talent; but in his pasos or prose interludes he displays an abundance of riotous humour, great knowledge of low life, and a most happy gift of dialogue. His works in the genre include Las accitunas (The Olive Trees). Cornudo y contento (Cuckolded and Content), El condidado (The Guest), Los criados (The Servants), and Los lacayos lardones (The Thieving Lackeys). [3]

Discordia y cuestion de amor (Discord and a Question of Love) is a rhymed pastoral play. Auto de Naval y Abigail (The Story of Naval and Abigail) is an Auto sacramental play based on the Bible.

He disdained the use of bombastic language and what he considered an excessive use of deus ex machina by other playwrights.

His predecessors mostly wrote for courtly audiences or for the study; de Rueda with his strollers created a taste for the drama which he was able to gratify, and he is admitted both by Cervantes and Lope de Vega to be the true founder of the national theatre.

His works have been reprinted by the marqués de Fuensanta del Valle in the Colección de libros raros curiosos, vols. xxiii. and xxiv.

Modern adaptation[]

Nineteen of the 26 pasos were translated into English between 1980 and 1990 by Joan Bucks Hansen, and staged by Steve Hansen and the St. George Street Players of St. Augustine,FL where they were performed nightly for five years in the city's restored Spanish Quarter; and they presented seven of the translations in 1984 at the Ninth Siglo de Oro Festival at Chamizal.[4]

Personal life[]

He was twice married; first to actress, singer and dancer, Mariana, who had spent six years as a performer in service to the frail and infirm Don Gaston, Duke de Medinaceli, an avowed friar and cleric, whose estate was the subject of a lawsuit filed by Lope de Rueda on his wife's behalf laying claim to six years of back wages. de Rueda's second marriage was to Rafaela Angela, a Valenciana and woman of property, who bore him a daughter.

Death[]

In Córdoba, de Rueda fell ill, and on 21 March 1565 made a will which he was too exhausted to sign; he probably died shortly afterwards, and is said by Cervantes to have been buried in Córdoba cathedral.[1]

Notes[]

This article includes a list of general references, but it remains largely unverified because it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (January 2014) |

- ^ Jump up to: a b c . Encyclopædia Britannica. 23 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 818.

- ^ Boccaccio, Decameron, 9, II

- ^ List of plays copied from the Hebrew-language article in the Hebrew Encyclopedia, Jerusalem/Tel Aviv 1969, Vol. 21, p. 507, article by Moshe Lazar

- ^ Nineteen pasos translated into English

Further reading[]

- A.L. Stiefel, Lope de Rueda und das italiensche Lustspiel (Zietschrift fur Rom. Philol. XV, 1891)

- M. Ferrer Izquierdo, Lope de Rueda, 1899

- E. Cotarelo y Mori, Lope de Rueda y el teatro espanol de su tiempo (Estudios de Historia Literaria de Espana 183-290), 1901

- W.H. Chambers, The Seven Faces of Lope de Rueda, 1903

- S. Salazar, Lope de Rueda y su teatro, 1912

- J.P.W. Crawford, Spanish Drama before Lope de Vega (ch. IV), 1937

- T. Villacorta Mas, Lenguaje coloquial en Lope de Rueda (Ph. D. thesis, 1955.

References[]

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Rueda, Lope de". Encyclopædia Britannica. 23 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 818.

- Spanish Golden Age

- 1510s births

- 1565 deaths

- People from Seville

- Spanish male dramatists and playwrights

- 16th-century dramatists and playwrights

- 16th-century theatre managers