Lotte Reiniger

Lotte Reiniger | |

|---|---|

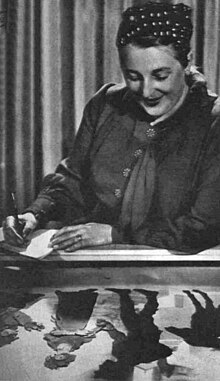

Reiniger in 1939 | |

| Born | Charlotte Reiniger 2 June 1899 |

| Died | 19 June 1981 (aged 82) |

| Occupation | Silhouette animator, film director |

| Years active | 1918–1979 |

Notable work | The Adventures of Prince Achmed (1926) |

| Spouse(s) | Carl Koch |

Charlotte "Lotte" Reiniger (2 June 1899 – 19 June 1981) was a German film director and the foremost pioneer of silhouette animation. Her best known films are The Adventures of Prince Achmed, from 1926, the first feature-length animated film, and Papageno (1935). Reiniger is also noted for having devised the first form of a multiplane camera;[1] she made more than 40 films, all using her invention.[2]

Biography[]

Early life[]

Lotte Reiniger was born in the Charlottenburg district of Berlin on 2 June 1899 to Carl Reiniger and Eleonore Lina Wilhelmine Rakette.[3] As a child, she was fascinated with the Chinese arts of paper cutting of silhouette puppetry, even building her own puppet theatre so that she could put on shows for her family and friends.[1]

As a teenager, Reiniger developed a love of cinema, first with the films of Georges Méliès for their special effects, then the films of the actor and director Paul Wegener, known today for The Golem (1920). In 1915, she attended a lecture by Wegener that focused on the fantastic possibilities of animation.[1] Reiniger eventually convinced her parents to allow her to enroll in the acting group to which Wegener belonged, the Theatre of Max Reinhardt. She began by making costumes and props and working backstage.[4] She started making silhouette portraits of the various actors around her, and soon she was making elaborate title cards for Wegener's films, many of which featured her silhouettes.[citation needed]

Adulthood and success[]

In 1918, Reiniger animated wooden rats and created the animated intertitles for Wegener's Der Rattenfänger von Hameln (The Pied Piper of Hamelin). The success of this work got her admitted into the Institut für Kulturforschung (Institute for Cultural Research), an experimental animation and shortfilm studio. It was here that she met her future creative partner and husband (from 1921), Carl Koch, as well as other avant-garde artists including Hans Cürlis, Bertolt Brecht, and Berthold Bartosch.[5]

The first film Reiniger directed was Das Ornament des verliebten Herzens (The Ornament of the Enamoured Heart, 1919), a five-minute piece involving two lovers and an ornament that reflects their moods. The film was very well received,[1] and its success opened up many new connections for Reiniger in the animation industry.[4]

She made six short films over the next few years, all produced and photographed by her husband, including the fairytale animation Aschenputtel (1922).[6] These shorts were interspersed with advertising films (the Julius Pinschewer advertising agency innovated ad films and sponsored a large number of abstract animators during the Weimar period) and special effects for various feature films—most famously a silhouette falcon for a dream sequence in Part One of Die Nibelungen by Fritz Lang. During this time, she found herself at the centre of a large group of ambitious German animators, including Bartosch, Hans Richter, Walter Ruttmann and Oskar Fischinger.[5]

In 1923, she was approached by Louis Hagen, who had bought a large quantity of raw film stock as an investment to fight the spiraling inflation of the period. He asked her to do a feature-length animated film. There was some difficulty that came with doing this, however. Reiniger is quoted as saying "We had to think twice. This was a never heard of thing. Animated films were supposed to make people roar with laughter, and nobody had dared to entertain an audience with them for more than ten minutes. Everybody to whom we talked in the industry about the proposition was horrified."[4] The result was The Adventures of Prince Achmed, completed in 1926, one of the first animated feature films, with a plot that is a pastiche of stories from One Thousand and One Nights. Although it failed to find a distributor for almost a year, once premiered in Paris (thanks to the support of Jean Renoir), it became a critical and popular success.[7] Because of this delay, however, The Adventures of Prince Achmed's expressionistic style did not quite fit with the realism that was becoming popular in cinema in 1926.[8] Reiniger uses lines that can almost be called "colorful" to represent the film's exotic locations.[9] Today, The Adventures of Prince Achmed is thought to be one of the oldest surviving feature-length animated films, if not the oldest.[8] It is also considered to be the first avant-garde full-length animated feature.[4]

Reiniger, in devising a predecessor to the multiplane camera for certain effects, preceded Ub Iwerks and Walt Disney by a decade. Above her animation table, a camera with a manual shutter was placed in order to achieve this. She placed planes of glass to achieve a layered effect. The setup was then backlit. This camera setup was later invented simultaneously and innovated in cel animation.[4] Reiniger wrote instructions on how to construct her "trick-table" in her book, Shadow puppets, shadow theatres, and shadow films.[10] In addition to Reiniger's silhouette actors, Prince Achmed boasted dream-like backgrounds by Walter Ruttmann (her partner in the Die Nibelungen sequence) and Walter Türck, and a symphonic score by Wolfgang Zeller. Additional effects were added by Carl Koch and Berthold Bartosch.[11]

Following the success of Prince Achmed, Reiniger was able to make a second feature. Doktor Dolittle und seine Tiere (Doctor Dolittle and his Animals, 1928) was based on the first of the English children's books by Hugh Lofting. The film tells of the good Doctor's voyage to Africa to help heal sick animals. It is currently available only in a television version with new music, voice-over narration and the images playing at too many frames per second. The score of this three-part film was composed by Kurt Weill, Paul Hindemith and Paul Dessau.[12]

A year later, Reiniger co-directed her first live-action film with Rochus Gliese, Die Jagd nach dem Glück (The Pursuit of Happiness, 1929), a tale about a shadow-puppet troupe. The film starred Jean Renoir and Berthold Bartosch and included a 20-minute silhouette performance by Reiniger. Unfortunately, the film was completed just as sound came to Germany and release of the film was delayed until 1930 to dub in voices by different actors—the result being disappointing.[12]

Reiniger attempted to make a third animated feature, inspired by Maurice Ravel's opera L'enfant et les sortilèges (The Child and the Bewitched Things, 1925), but was unable to clear all of the individual rights to Ravel's music, the libretto (by the novelist Colette), and an unexpected number of copyright holders. When Ravel died in 1937 the clearance became even more complex and Lotte finally abandoned the project, although she had designed sequences and animated some scenes to convince potential backers and the rights-holders.[12]

Reiniger worked on several films with British poet, critic, and musician Eric Walter White, who wrote an early book-length essay on her work.[13]

Flight from Germany and later life[]

With the rise of the Nazi Party, Reiniger and Koch decided to emigrate (both were involved in left-wing politics),[12][14] but found that no other country would give them permanent visas. As a result, the couple spent the years 1933–1944 moving from country to country, staying as long as visas would allow. With the release of sound film, Reiniger and her husband began to work with music in relation to animation.[4] They worked with film-makers Jean Renoir in Paris and Luchino Visconti in Rome. They managed to make 12 films during this period, the best-known being Carmen (1933) and Papageno (1935), both based on popular operas (Bizet's Carmen and Mozart's Die Zauberflöte). When World War II commenced they stayed with Visconti in Rome until 1944, then moved back to Berlin to take care of Reiniger's sick mother.[15] Under the rule of Hitler, Reiniger was forced to make propaganda films for Germany. One of these films is called Die goldene Gans (The Golden Goose, 1944). She had to work under stringent and limiting conditions to please the German state, which is why some of her work in this time period may appear creatively stifled.[4]

In 1949, Reiniger and Koch moved to London, where she made a few short advertising films for John Grierson and his General Post Office Film Unit (later to be renamed the "Crown Film Unit").[12] While she was living in London in the early 1950s she became friends with Freddy Bloom, the chair of the National Deaf Children's Society and editor of quarterly magazine called "TALK", who asked her to design a logo. Reiniger responded by cutting out silhouettes of four children running up a hill. Freddy Bloom was amazed at her skill with the scissors—in a few moments she created about four different silhouettes of the children from black paper. One of them was used as cover design on the magazine TALK from 1956. The logo was used until the 1990s, when a design company was invited to revamp it. The result was a very minor modification, but this new design was dropped a few years later. In the early 1950s she was working at Beconsfield studios in Buckinghamshire.[citation needed]

With Louis Hagen Jr. (the son of Reiniger's financier of Prince Achmed in Potsdam), they founded Primrose Productions in 1953 and, over the next two years, produced more than a dozen short silhouette films based on Grimms' Fairy Tales for the BBC and Telecasting America.[15] Reiniger also provided illustrations for the 1953 book King Arthur and His Knights of the Round Table by Roger Lancelyn Green.[citation needed]

After a period of seclusion after her husband's death in 1963, renewed interest in her work resulted in Reiniger's return to Germany. She later visited the United States, and began making films again soon after. She made three more films, the last of which, Die vier Jahreszeiten, was completed the year before she died.[16]

Reiniger was awarded the Filmband in Gold of the Deutscher Filmpreis in 1972; in 1979 she received the Great Cross of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany.[15] Reiniger died in Dettenhausen, Germany, on 19 June 1981, just after her 82nd birthday.[5]

Art style[]

Reiniger had a distinct art style in her animations that was very different from other artists in the time period of the 1920s and the 1930s, particularly in terms of characters. In the 1920s especially, characters tended to rely on facial expressions to express emotions or action, while Reiniger's characters relied on gestures to display emotions or actions. She also utilized the technique of metamorphosis often in her animations. This focus on transformation greatly benefits her tendency to work with fairytale stories. The Adventures of Prince Achmed specifically adapts fantastic elements to take advantage of animation to show things that could not be shown in reality.[5] Reiniger considered animation's separation from the laws of the material plane to be one of the greatest strengths of the medium.[17][18]

Because of this, Reiniger's characters are not usually biologically correct, but they are able to express a fluidity which is very important to her style of expressionism. Although there are other animators in that time period that used these techniques, Reiniger stands out because she is able to accomplish this style using cutout animation.[8] Reiniger's figures resemble stop-motion animation in the way that they move.[19]

Influence[]

Reiniger's black silhouettes would become a popular aesthetic to reference in films and art. Although all subsequent makers of animated fairy tales could be said to have been influenced by Reiniger, Bruno J. Böttge is probably the one who has made the most explicit references to her work.[citation needed]

Disney's Fantasia uses Reiniger's style in the beginning of the scene where Mickey Mouse is in the same shot as the live-action musicians,[4] as well as in The Princess and the Frog during the musical number "Friends on the Other Side".[20]

Disney would also use a multipleplane camera in its own movies, such as Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, based on the technology that Reiniger originally developed.[21]

Starting with the silhouette format in the 1989 television series Ciné si, French animator Michel Ocelot employs many of the techniques created by Reiniger, along with others of his own invention, in his silhouette film Princes et princesses.[22]

Bram Stoker's Dracula briefly included a silhouetted scene in its opening a homage to early cinema technique like Reiniger's.[23]

The animated series South Park uses a paper cut-out style reminiscent of Reiniger's.

Reiniger's cut-out animation style was utilized in the credits of the 2004 film Lemony Snicket's A Series of Unfortunate Events.[24]

In the 2010 film, Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows – Part 1, animator Ben Hibon used Reiniger's style of animation in the short film titled "The Tale of the Three Brothers".[25]

The animated series Steven Universe paid homage to the style of Reiniger's films in the episode "The Answer".[26]

Legacy[]

The municipal museum in Tübingen holds much of her original materials and hosts a permanent exhibition, "The World in Light and Shadow: Silhouette, shadow theatre, silhouette film".[27] The Filmmuseum Düsseldorf also holds many materials of Lotte Reiniger's work, including her animation table, and a part of the permanent exhibition is dedicated to her.[28] Collections relating to her are also held at the BFI National Archive.[29]

On June 2, 2016, Google celebrated Reiniger's 117th birthday with a Google Doodle about her.[30][31]

Filmography[]

- 1919 – The Ornament of the Lovestruck Heart

- 1920 – Amor and the Steady Loving Couple

- 1921 – The Star of Bethlehem

- 1922 – Sleeping Beauty

- 1922 – The Flying Suitcase

- 1922 – The Secret of the Marquise

- 1922 – Cinderella

- 1926 – The Adventures of Prince Achmed (feature)

- 1927 – The Chinese Nightingale

- 1928 – Dr. Dolittle and His Animals (3 parts: "The Journey to Africa", "The Monkey Bridge", "The Monkey Illness")

- 1930 – Chasing Fortune

- 1930 – Ten Minutes of Mozart

- 1931 – Harlekin

- 1932 – Sissi

- 1933 – Carmen

- 1934 – The Stolen Heart

- 1935 – The Seemingly Dead Chinese

- 1935 – The Little Chimney Sweep

- 1935 – Galathea: The Living Marblestatue

- 1935 – Die Jagd nach dem Glück (Hunt for Luck)

- 1935 – Kalif Storch

- 1935 – Papageno

- 1936 – Silhouettes (animation scenes)

- 1936 – Puss in Boots

- 1937 – The Tocher. Film Ballet

- 1938 – The HPO – Heavenly Post Office

- 1942 – Girl of the Golden West (writer)

- 1944 – The Goose That Lays the Golden Eggs

- 1951 – Mary's Birthday

- 1953 – The Magic Horse

- 1954 – Aladdin and the Magic Lamp

- 1954 – Caliph Storch

- 1954 – Cinderella

- 1954 – Puss in Boots

- 1954 – Snow White and Rose Red

- 1954 – The Frog Prince

- 1954 – The Gallant Little Tailor

- 1954 – The Grasshopper and the Ant

- 1954 – The Little Chimney Sweep

- 1954 – The Sleeping Beauty

- 1954 – The Three Wishes

- 1954 – Thumbelina

- 1955 – Hansel and Gretel

- 1955 – Jack and the Beanstalk

- 1961 – The Frog Prince

- 1974 - The Lost Son

- 1975 – Aucassin and Nicolette

- 1979 – The Rose and the Ring

- 1980 – Die vier Jahreszeiten (The Four Seasons)

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "The life of Lotte Reiniger". Drawn to be Wild. BFI. Archived from the original on 2001-03-03. (an extract from Pilling, Jayne, ed. (1992). Women and Animation: a Compendium. BFI. ISBN 0-85170-377-1.)

- ^ The Art of Lotte Reiniger, parte 1 on YouTube

- ^ Dresden, Germany, Marriages, 1876–1922, and Berlin, Germany, Births, 1877–1899 (in German), indexed in Ancestry.com.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h "Stranger Magic". Sight & Sound.[full citation needed]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Schönfeld, Christiane (2006). Practicing Modernity: Female Creativity in the Weimar Republic. Konigshausen & Neumann. p. 174.

- ^ Ludwig, R. "Fairy Tale Flappers: Animated Adaptations of Little Red and Cinderella (1922–1925)". governmentcheese.ca. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- ^ Ratner, Megan (2006). "In the Shadows". Art on Paper. 10 (3): 44–49. JSTOR 24556712.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Life and Death in the Shadows: Lotte Reiniger's Die Abenteuer des Prinzen Ahmed". German Life and Letters.[full citation needed]

- ^ Haase, Donald. "The Arabian Nights, Visual Culture, and Early German Cinema". Fabula – via ProQuest.

- ^ Reiniger, Lotte (1975). Shadow puppets, shadow theatres, and shadow films. Boston: Plays, Inc. ISBN 0823801985. OCLC 1934547.

- ^ Practicing modernity: female creativity in the Weimar Republic. Schönfeld, Christiane., Finnan, Carmel, 1958–. Würzburg: Königshausen & Neumann. 2006. ISBN 3826032411. OCLC 71336738.CS1 maint: others (link)

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Moritz, William (1996). "Lotte Reiniger". AWN.com. Retrieved 2016-06-02.

- ^ White, Eric Walter (1931). Walking Shadows: An Essay on Lotte Reiniger's Silhouette Films. London: Leonard and Virginia Woolf.

- ^ Moritz, William (Fall 1996). "Some Critical Perspectives on Lotte Reiniger". Animation Journal. 5 (1): 40–51.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Kemp, Philip. "Reiniger, Lotte (1899–1981)". BFI Screenonline.

- ^ Cavalier, Stephen (2011). The world history of animation. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. ISBN 9780520261129. OCLC 668191570.

- ^ Kaes, Anton; Baer, Nicholas; Cowan, Michael J., eds. (March 2016). The promise of cinema: German film theory, 1907–1933. Oakland. ISBN 978-0520962439. OCLC 938890898.

- ^ Donald, Crafton (1993). Before Mickey: the animated film, 1898-1928. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0226116670. OCLC 28547443.

- ^ "Paper Scissors". Sight & Sound – via ProQuest.[full citation needed]

- ^ "The lasting legacy of Lotte Reiniger". www.acmi.net.au. Retrieved 2021-03-16.

- ^ "The lasting legacy of Lotte Reiniger". www.acmi.net.au. Retrieved 2021-03-16.

- ^ Jouvanceau, Pierre (2004). The Silhouette Film. Genoa: Le Mani. ISBN 88-8012-299-1. Archived from the original on 2014-10-06. Retrieved 2012-09-29.

- ^ "The lasting legacy of Lotte Reiniger". www.acmi.net.au. Retrieved 2021-03-16.

- ^ "Lemony Snicket's a Series of Unfortunate Events". Sight & Sound – via ProQuest.[full citation needed]

- ^ Warner, Marina (2012). Stranger Magic: Charmed States and the Arabian Nights. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. p. 394. ISBN 9780674055308. JSTOR j.ctt2jbtr6. OCLC 758383788.

- ^ Jusino, Teresa (30 November 2015). "Some of Comics' Biggest Names Shout-Out Their Favorite Female Creators". The Mary Sue. Retrieved 2016-06-02.

- ^ "Lotte Reiniger". Stadtmuseum Tübingen. Retrieved 2016-06-02.

- ^ Düsseldorf, Landeshauptstadt. "Landeshauptstadt Düsseldorf – Über das Filmmuseum". www.duesseldorf.de. Archived from the original on 2016-06-24. Retrieved 2016-06-24.

- ^ White, James (2015-12-21). "Lotte Reiniger and The Star of Bethlehem". BFI. Retrieved 2016-06-02.

- ^ "New Google Doodle Celebrates German Animator Lotte Reiniger". TIME. Retrieved 2 June 2016.

- ^ "Lotte Reiniger's 117th birthday". Retrieved 2016-06-02.

Bibliography[]

- Bendazzi, Giannalberto (Anna Taraboletti-Segre, translator). Cartoons: One Hundred Years of Cinema Animation. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-20937-4 (reprint, paperback, 2001).

- Cavalier, Steven. The world history of animation // Animation. Berkeley : University of California Press, 2011. ISBN 9780520261129

- Crafton, Donald. Before Mickey: The Animated Film, 1898–1928. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-11667-0 (2nd edition, paperback, 1993).

- Giesen, Rolf (2012). Animation Under the Swastika. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc. p. 200. ISBN 978-0-7864-4640-7.

- Kaes, Anton, Michael Cowan and Nicholas Baer, eds. (2016). The Promise of Cinema: German Film Theory, 1907–1933. Oakland: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-96243-5

- Moritz, William. "Some Critical Perspectives on Lotte Reiniger." Animation Journal 5:1 (Fall 1996). 40–51.

- Leslie, Esther. Hollywood Flatlands: Animation, Critical Theory and the Avant-Garde. London: Verso, 2002. ISBN 9781844675043.

- Reiniger, Lotte. Shadow Theatres and Shadow Films. London: B.T. Batsford Ltd., 1970. Print.

- Schönfeld, Christiane. (2006). Practicing modernity : female creativity in the Weimar Republic. Würzburg : Königshausen & Neumann. ISBN 3826032411

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lotte Reiniger. |

- Lotte Reiniger at IMDb

- "Lotte Reiniger's Silhouettes" by Abhijit Ghosh Dasitidar

- Essay on Reiniger by William Moritz (includes filmography)

- Profile of Reiniger at the Women Film Pioneers website

- "Lotte Reiniger" by Christine Ott (in French)

- 1899 births

- 1981 deaths

- German animated film directors

- German animated film producers

- Commanders Crosses of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany

- Film directors from Berlin

- German women film directors

- Stop motion animators

- Women animators

- Women film pioneers