Lublin Castle

| Lublin Royal Castle Zamek Lubelski (in Polish) | |

|---|---|

Lublin Castle | |

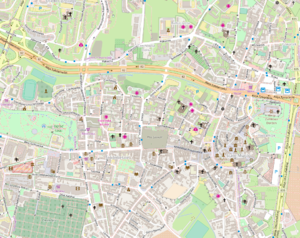

Location within the city of Lublin | |

| General information | |

| Architectural style | Polish Gothic-Gothic Revival |

| Town or city | Lublin |

| Country | Poland |

| Coordinates | 51°15′02″N 22°34′20″E / 51.25056°N 22.57222°E |

| Construction started | 12th century |

| Demolished | 1655−1657, rebuilt 1826-1828 as prison |

| Client | Casimir II the Just |

The Lublin Castle (Polish: Zamek Lubelski) is a medieval castle in Lublin, Poland, adjacent to the Old Town district and close to the city center. It is one of the oldest preserved Royal residencies in Poland, established by High Duke Casimir II the Just.[1]

History[]

The hill it is on was first fortified with a wood-reinforced earthen wall in the 12th century. In the first half of the 13th century, the stone keep was built. It survives to this day[1] and is the tallest building of the castle, as well as the oldest standing building in the city. In the 14th century, during the reign of Casimir the Great, the castle was rebuilt with stone walls. Probably at the same time the castle's Chapel of the Holy Trinity was built to serve as a royal chapel.[1]

In the first decades of the 15th century king Władysław II commissioned a set of frescoes for the chapel. They were completed in 1418 and are preserved to this day.[2] The author was a Ruthenian Master Andrej, who signed his work on one of the walls.[2] Due to their unique style, mixing Western and Eastern Orthodox influences, they are acclaimed internationally as an important historical monument.[1]

Under the rule of the Jagiellon dynasty the castle enjoyed royal favor and frequent stays by members of the royal family. In the 16th century, it was rebuilt on a grandiose scale, under the direction of Italian masters brought from Kraków. The most momentous event in the castle's history was the signing in 1569 of the Union of Lublin, the founding act of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth.

As a consequence of the wars in the 17th century (The Deluge) the castle fell into disrepair.[1] Only the oldest sections, the keep and the chapel, remained intact. After Lublin fell under Russian rule following the territorial settlement of the Congress of Vienna in 1815, the government of Congress Poland, on the initiative of Stanisław Staszic, carried out a complete reconstruction of the castle between 1826 and 1828.[1] The new buildings were in English neogothic style, completely different from the structures they replaced, and their new purpose was to house a criminal prison.[1] Only the keep and the chapel were preserved in their original state.

The castle served as a prison for the next 128 years: as a Tsarist prison from 1831 to 1915, in independent Poland from 1918 to 1939, and most infamously during the Nazi occupation of the city from 1939 to 1944, when between 40,000 and 80,000 inmates, many of them Polish resistance fighters and Jews, passed through.[3] Just before withdrawing in 1944, the Nazis massacred its remaining 300 prisoners. After 1944 the castle continued to serve as a prison of Soviet secret police and later of the People's Republic of Poland, and until 1954 about 35,000 Poles fighting against the new communist government (especially cursed soldiers) passed through it, of whom 333 lost their lives.[1]

In 1954 the castle prison was closed. Following reconstruction and refurbishment, since 1957 it has been the main site of the Lublin Museum.

Gallery[]

View of the castle in 1826

Main entrance gate of the neo-gothic part of the building

The keep and the Holy Trinity Chapel seen from the castle's courtyard

Courtyard of the castle

See also[]

- Castles in Poland

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h (in English) "A Brief History of Lublin Castle". eng.zamek.lublin.pl. Archived from the original on 2011-08-15. Retrieved 2010-09-15.

- ^ Jump up to: a b (in English) Tomasz Torbus (1999). Poland. Hunter Publishing, Inc. p. 86. ISBN 3-88618-088-3.

- ^ (in English) Joseph Poprzeczny (2004). Odilo Globocnik, Hitler's man in the East. McFarland. p. 230. ISBN 0-7864-1625-4.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lublin Castle. |

- Buildings and structures in Lublin

- Castles in Lublin Voivodeship

- Gothic Revival architecture in Poland

- Historic house museums in Poland

- History of Lublin

- Museums in Lublin Voivodeship

- Residences of Polish monarchs

- Royal residences in Poland

- Buildings and structures in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth