MacDonald of Glencoe

This article uses bare URLs, which may be threatened by link rot. (May 2021) |

This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2009) |

The MacDonalds of Glencoe, also known as Clann Iain Abrach, was a Highland Scottish clan and a branch of the larger Clan Donald. They were named after Glen Coe.

History[]

Origins of the clan[]

The founder of the MacDonalds of Glencoe was Iain Fraoch MacDonald (d. 1368) who was a son of Aonghus Óg of Islay (died 1314×1318/c.1330), chief of Clan Donald, who fought alongside King Robert the Bruce at the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314.[1]

It is believed that Angus Og never married the daughter of MacEanruig or MacHenry the 'head man' in Glencoe.[2] Instead, he married Aine O'Cahan of Ulster who gave birth to his legitimate heir, John of Islay, who became Lord of the Isles.

Angus Og gained the lands of Glencoe from Robert the Bruce who, after the Battle of Bannockburn, bestowed these lands on him as well as others. In turn, Angus Og gave his natural son, Iain Fraoch, Glencoe.

Glencoe was an ever hostile environment whose sparse soil drove people to theft, raiding and stealing cattle from their neighbours.

The Massacre of Glencoe[]

The Glencoe MacDonalds were one of three Lochaber clans with a reputation for lawlessness, the others being the MacGregors and the Keppoch MacDonalds. Levies from these clans served in the Independent Companies used to suppress the Conventicles in 1678–80, and took part in the devastating Atholl raid that followed Argyll's Rising in 1685.[3] This made them an obvious target when the Duke of Argyll returned to power after the 1688 Glorious Revolution in Scotland.[4]

During the 1689- 1692 Jacobite rising, the Scottish government held a series of meetings with the Jacobite chiefs. In March 1690, the Secretary of State, Lord Stair, offered a total of £12,000 for swearing allegiance to William III. They agreed to do so in the June 1691 Declaration of Achallader, the Earl of Breadalbane signing for the government.[5]

On 26 August, a Royal Proclamation offered a pardon to anyone taking the Oath prior to 1 January 1692, with severe reprisals for those who did not. Two days later, secret articles appeared, cancelling the agreement in the event of a Jacobite invasion and signed by all the attendees, including Breadalbane, who claimed they had been manufactured by MacDonald of Glengarry.[6] Stair's letters increasingly focused on enforcement, reflecting his belief forged or not, none of the signatories intended to keep their word, and so an example was required.[7]

In early October, the chiefs asked the exiled James II for permission to take the Oath unless he could mount an invasion before the deadline, a condition they knew to be impossible.[8] His approval was sent on 12 December, and received by Glengarry on the 23rd, who did not share it until the 28th. One suggestion it was driven by an internal power struggle between Protestant elements of the MacDonald clan, like Glencoe, and the Catholic minority, led by Glengarry. Delayed by heavy snow, the Glencoe chief was late taking the oath, but Glengarry himself did not swear until early February.[9]

The exact reason for the selection of the Glencoe MacDonalds remains unclear, but led to the Massacre of Glencoe (Gaelic: Mort Ghlinne Comhann) in the early hours of the 13th of February 1692. This was carried out by troops quartered on the Macdonalds, commanded by Robert Campbell of Glenlyon; the number of deaths is disputed, the often quoted figure of 38 being based on hearsay evidence, while the MacDonalds claimed 'the number they knew to be slaine were about 25.'[10] Recent estimates put total deaths resulting from the Massacre as 'around 30', while claims others died of exposure have not been substantiated.[11]

Although the action itself was widely condemned, there was limited sympathy for the MacDonalds; the government commander in Scotland, Thomas Livingstone, commented in a letter; 'It's not that anyone thinks the thieving tribe did not deserve to be destroyed, but that it should have been done by those quartered amongst them makes a great noise.'[12]

Post 1692[]

The Glencoe Macdonalds rebuilt their houses, taking part in the Jacobite risings of 1715 and 1745. In 2018, a team of archaeologists organised by the National Trust for Scotland began surveying several areas related to the massacre, with plans to produce detailed studies of their findings.[13] Work in the summer of 2019 focused on the settlement of Achtriachtan, at the extreme end of the glen; home to an estimated 50 people, excavations show it was rebuilt after 1692. It was still occupied in the mid-18th century, but by 1800 the area was deserted.[14]

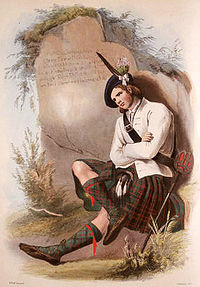

Clan Tartan[]

The clan's tartan is sold as MacIain/MacDonald of Glencoe but sometimes is often sold as MacDonald of Ardnamurchan through confusion of both clans being known as MacIains. There is a separate tartan known as the MacDonald of Glencoe, it is very different from the MacIan or the Ardnamuchan. This is the proper tartan for Glencoe and was found on the bodies exhumed in the 1800s for burial in consecrated ground. This is an ancient tartan and predates the Highland Clearances.

List of clan chiefs[]

The following is a list of the historic chiefs of the Clan MacDonald of Glencoe:

- Iain Og an Fraoch MacDonald, 1st of Glencoe (Abt 1300 – 1358), (son of Aonghus Óg of Islay)

- John MacIain MacDonald, 2nd of Glencoe (Bef 1358)

- John MacIain MacDonald, 3rd of Glencoe

- John MacIain MacDonald, 4th of Glencoe

- John MacIain MacDonald, 5th of Glencoe

- John MacIain MacDonald, 6th of Glencoe

- John MacIain MacDonald, 7th of Glencoe

- Iain Og MacIain MacDonald, 8th of Glencoe (1543 – Abt 1590)

- Iain Og MacIain MacDonald, 9th of Glencoe (1579–1610)

- Iain Abrach MacDonald, 10th of Glencoe ( – 1630)

- Alasdair Ruadh MacIain MacDonald, 11th of Glencoe ( – 1650)

- Alasdair Ruadh MacIain MacDonald, 12th of Glencoe (1630–1692) (Killed at the Massacre of Glencoe)

- John MacIain MacDonald, 13th of Glencoe (1657–1714)

- Alexander MacIain MacDonald, 14th of Glencoe (1708–1750)

- John MacIain MacDonald, 15th of Glencoe (Abt 1735 – 1785)

- Alexander MacIain MacDonald, 16th of Glencoe (1761–1814)

- Dr. Ewen MacIain MacDonald, 17th of Glencoe, H.E.I.C.S. (1788–1840)

- Ronald MacIain MacDonald, 18th of Glencoe (1800–1841) (brother of 17th)

- Alexander James MacDonald, 19th of Glencoe (1829–1889)[15]

Disputed chiefship[]

The Cameron Henry of Penicuik is currently claiming clan chief through ancestry by sept Henry. They are represented by the High Chief of Clan Donald. Currently there are 4 contenders for MacDonald of Glencoe Chiefship.[citation needed]The families descended from James Cameron of Madagascar are as well preparing a claim. It is anticipated that this matter will be settled by Lord Lyon King of Arms in the next few years.[citation needed]

Septs of the Clan[]

The list of Septs of the Clan MacDonald of Glencoe is:

Culp, Henderson, Hendrie, Hendry, Henry, Johnson, Kean, Keene, Keane, MacDonald, MacGilp, MacHendrie, MacHendry, MacHenry, MacIan, MacIsaac, MacKean, McKean, McKendrick, McKern, MacKern, MacKillop, MacPhilip, Moor, Philip, Philp[16][17]

See also[]

References[]

- ^ The Family Tree of the Lords of the Isles – Finlaggan Trust Archived 2010-07-04 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Macdonald genealogy, Roddy Macdonald of the Clan Donald Society of Edinburgh, (http://www.clandonald.org.uk/genealogy.htm)genealogy/d0002/g0000050.html#I0043.

- ^ Levine 1999, p. 128.

- ^ Levine 1999, p. 137.

- ^ Harris 2007, p. 439.

- ^ Levine 1999, p. 139.

- ^ Gordon 1845, pp. 238.

- ^ Szechi 1994, p. 45.

- ^ Szechi 1994, p. 30.

- ^ Cobbett 1814, pp. 902–903.

- ^ Campsie.

- ^ Preeble 1973, p. 197.

- ^ Treviño.

- ^ MacDonald.

- ^ Alexander James MacDonald, 19th of Glencoe clanmacfarlanegenealogy.info. Retrieved May 30, 2016.

- ^ Scots Kith and Kin, Revised Second Edition; published by Albyn Press LTD, Edinburgh, p. 65

- ^ http://johnmoorefamily.org/info_john_moor_1.htm

Sources[]

- Campsie, Alison (12 February 2018). "The Scotsman". Archaeologists trace lost settlements of Glencoe destroyed after 1692 massacre. Retrieved 3 July 2018.

- Cobbett, William (1814). Cobbett's Complete Collection Of State Trials And Proceedings For High Treason And Other Crimes And Misdemeanors. Nabu Press. ISBN 1175882445.

- Levine, Mark (editor) (1999). The Massacre in History (War and Genocide). Bergahn Books. ISBN 1571819355.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- MacDonald, Kenneth (11 May 2019). "The dig uncovering Glencoe's dark secrets". BBC. Retrieved 13 October 2019.

- Prebble, John (1968). Darien: the Scottish Dream of Empire (2002 ed.). Pimlico. ISBN 978-0712668538.

- Szechi, Daniel (1994). The Jacobites: Britain and Europe, 1688–1788. Manchester University Press. ISBN 0719037743.

- Treviño, Julissa (26 March 2018). "Archaeologists Trace 'Lost Settlements' of 1692 Glencoe Massacre". smithsonianmag.com. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

External links[]

- Clan Donald

- Lochaber

- Glen Coe