Madaba Map

Coordinates: 31°43′3.54″N 35°47′39.12″E / 31.7176500°N 35.7942000°E

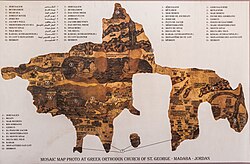

The Madaba Map, also known as the Madaba Mosaic Map, is part of a floor mosaic in the early Byzantine church of Saint George in Madaba, Jordan. The Madaba Map is of the Middle East, and part of it contains the oldest surviving original cartographic depiction of the Holy Land and especially, Jerusalem. It dates to the sixth century AD.

History[]

The Madaba Mosaic Map depicts Jerusalem with the New Church of the Theotokos, which was dedicated on 20 November 542. Buildings erected in Jerusalem after 570 are absent from the depiction, thus limiting the date range of its creation to the period between 542 and 570.[citation needed] The mosaic was made by unknown artists, probably for the Christian community of Madaba, which was the seat of a bishop at that time.

In 614, Madaba was conquered by the Sasanian Empire. In the eighth century, the ruling Muslim Umayyad Caliphate had some figural motifs removed from the mosaic. In 746, Madaba was largely destroyed by an earthquake and subsequently abandoned.

The mosaic was rediscovered in 1884, during the construction of a new Greek Orthodox church on the site of its ancient predecessor.[1] Patriarch Nicodemus I of Jerusalem was informed, but no research was carried out until 1896.[2][3]

In the following decades, large portions of the mosaic map were damaged by fires, activities in the new church, and by the effects of moisture. In December 1964, the Volkswagen Foundation gave the (lit. "German Association for the Exploration of Palestine") 90,000 DM to save the mosaic. In 1965, the archaeologists Heinz Cüppers and Herbert Donner undertook the restoration and conservation of the remaining parts of the mosaic.[citation needed]

Description[]

The floor mosaic is located in the apse of the church of Saint George at Madaba. It is not oriented northward, as modern maps are, but faces east toward the altar in such a fashion that the position of places on the map coincides with the compass directions. Originally, it measured 21 by 7 m and contained more than two million tesserae.[4] Its current dimensions are 16 by 5 m.

Topographic representation[]

The mosaic map depicts an area from Lebanon in the north to the Nile Delta in the south, and from the Mediterranean Sea in the west to the Eastern Desert. Among other features, it depicts the Dead Sea with two fishing boats, a variety of bridges linking the banks of the Jordan, fish swimming in the river and receding from the Dead Sea; a lion (rendered nearly unrecognisable by the insertion of random tesserae during a period of iconoclasm) hunting a gazelle in the Moab desert, palm-ringed Jericho, Bethlehem, and other biblical-Christian sites. The map may partially have served to facilitate pilgrims' orientation in the Holy Land.[citation needed] All landscape units are labelled with explanations in Greek. The mosaic's references to the tribes of Israel, toponymy, as well as its use of quotations of biblical passages, indicate that the artist who laid out the mosaic used the Onomasticon of Eusebius (fourth-century AD) as a primary source. A combination of folding perspective and an aerial view depicts approximately 150 towns and villages, all of them labelled.

The largest and most detailed element of the topographic depiction is Jerusalem (Greek: ΙΕΡΟΥΣΑ[ΛΉΜ]), at the centre of the map. The mosaic clearly shows a number of significant structures in the Old City of Jerusalem: the Damascus Gate, the Lions' Gate, the Golden Gate, the Zion Gate, the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, the New Church of the Theotokos, the Tower of David, and the Cardo Maximus. On Jerusalem's southwest side is shown Acel Dama (lit. "field of blood"), from Christian liturgy. The recognisable depiction of the urban topography makes the mosaic a key source on Byzantine Jerusalem. Also unique are the detailed depictions of cities such as Neapolis, Askalon, Gaza, Pelusium, and Charachmoba, all of them nearly detailed enough to be described as street maps. Other designated sites include: Nicopolis (Greek: ΝΙΚΟΠΟΛΙΣ); Beth Zachar[ias] (Greek: ΒΕΘΖΑΧΑΡ[ΊΟΥ]); Bethlehem (Greek: ΒΗΘΛΕΕΜ); Socho (Greek: Σωχω), now Kh. Shuweikah (southwest of Hebron); Beth Annaba (Greek: ΒΕΤΟΑΝΝΑΒΑ); Saphitha (Greek: CΑΦΙΘΑ);[5] Jericho (Greek: Ίεριχω); Beit-ḥagla (Greek: ΒΗΘΑΓΛΑ); Archelais (Greek: ΑΡΧΕΛΑΙϹ); Modi'im (Greek: ΜΩΔΕΕΙΜ); Lydda (Greek: ΛΩΔΗ); Bethoron (Greek: Βεθωρων); Gibeon (Greek: ΓΑΒΑΩΝ); Rama (Greek: ΡΑΜΑ); Coreae (Greek: ΚΟΡΕΟΥΣ);[6] Maresha (Greek: ΜΟΡΑΣΘΙ);[7] Azotos Paralos (Ashdod-Coast) (Greek: ΑΖΩΤΟΣΠΑΡΑΛΣ); The Great Plain (Greek: ΡΟΣΔΑΝ), literally meaning, "The Tribe of Dan";[8] Jamnia (Greek: ΊΑΒΝΗΛΗΚΑΙΊΑΜΝΙΑ) (Lit. "Jabneel, which is also Jamnia"), among other sites. Many of these sites are marked on the mosaic map with various artistic vignettes representing the site in the Province of Palestina Tertia. For example, Jericho and Zoar (Greek: ΖΟΟΡΑ) are, both, represented by vignettes of date palm orchards.[9] Zoar is seen on the far south-eastern side of the Dead Sea.

Scientific significance[]

The mosaic map of Madaba is the oldest known geographic floor mosaic in art history. It is used heavily for the localisation and verification of biblical sites. Study of the map played a major role in answering the question of the topographical location of Askalon (Asqalan on the map).[10]

In 1967, excavations in the Jewish Quarter of Jerusalem revealed the Nea Church and the Cardo Maximus in the very locations suggested by the Madaba Map.[11]

In February 2010, excavations further substantiated its accuracy with the discovery of a road depicted in the map that runs through the center of Jerusalem.[12] According to the map, the main entrance to the city was through a large gate opening into a wide central street. Until the discovery, archaeologists were not able to excavate this site due to heavy pedestrian traffic. In the wake of infrastructure work near the Jaffa Gate, large paving stones were discovered at a depth of four meters below ground that prove such a road existed.[13]

Copies of the Madaba Map[]

- The Archaeological Institute of Göttingen University contains a copy of the map in its archive collections. This copy was produced during the conservation work at Madaba in 1965 by archaeologists of the Rheinisches Landesmuseum, Trier.

- A copy produced by students of the Madaba Mosaic School is in the foyer of the Akademisches Kunstmuseum at Bonn.

- The lobby of the YMCA in Jerusalem has a replica of the map incorporated in the floor.[14]

See also[]

Chronological list of early Christian geographers and pilgrims to the Holy Land who wrote about their travels, and other related works

- Late Roman and Byzantine period

- Eusebius of Caesarea (260/65–339/40), Church historian and geographer of the Holy Land

- "Pilgrim of Bordeaux" (333-4), who left travel descriptions in the Itinerarium Burdigalense

- Egeria, pilgrim to the Holy Land (c. 381-384) who left a detailed travel account

- Jerome (Hieronymus; fl. 386-420), translator of the Vulgate version of the Bible, brought an important contribution to the topography of the Holy Land

- Anonymous pilgrim of Piacenza, pilgrim to the Holy Land (570s) who left travel descriptions

- Early Muslim period

- Chronicon Paschale, seventh-century Greek Christian chronicle of the world

- Arculf, Frankish Bishop and pilgrim to the Holy Land (c. 680) who left a detailed narrative of his travels

- Medieval period

- John of Würzburg, priest and pilgrim to the Holy Land (1160s) who left travel descriptions

References[]

- ^ Meimaris, Yiannis. "The Discovery of the Madaba Mosaic Map. Mythology and Reality". Archived from the original on 3 October 2013. Retrieved 9 June 2011.

- ^ Donner, 1992, p.11

- ^ Piccirillo, Michele (21 September 1995). "A Centenary to be celebrated". Jordan Times. Franciscan Archaeology Institute. Retrieved 18 January 2019.

It was only Abuna Kleofas Kikilides who realised the true significance, for the history of the region, that the map had while visiting Madaba in December 1896. A Franciscan friar of ltalian-Croatian origin born in Constantinople, Fr. Girolamo Golubovich, helped Abuna Kleofas to print a booklet in Greek about the map at the Franciscan printing press of Jerusalem. Immediately afterwards, the Revue Biblique published a long and detailed historic-geographic study of the map by the Dominican fathers M.J. Lagrange and H. Vincent after visiting the site themselves. At the same time. Father J. Germer-Durand of the Assumptionist Fathers published a photographic album with his own pictures of the map. In Paris, C. Clermont-Gannau, a well known oriental scholar, announced the discovery at the Academie des Sciences et belles Lettres.

- ^ http://www.uni-bonn.de/Aktuelles/Publikationen/forsch/forsch_4_November_2005/bilder/Kultur.pdf[permanent dead link] Ute Friederich: Antike Kartographie

- ^ Kallai-Kleinmann, Z. (1958). "The Town Lists of Judah, Simeon, Benjamin and Dan". Vetus Testamentum. Leiden: Brill. 8 (2): 155. JSTOR 1516086.

- ^ Where is now the "Old Roman Bridge" (Arabic: Mukatta' Damieh), near the confluence of the watercourse Naḥal Yabok, not far from Wadi Fara'a, and which once marked the entry into Judea when one passes over the midland countries.

- ^ Donner, Herbert (1995). The Mosaic Map of Madaba: An Introductory Guide. Palaestina antiqua 7 (2 ed.). Kampen, the Netherlands: Kok Pharos Publishing House. p. 22. ISBN 90-390-0011-5. OCLC 636083006.. This particular entry has inscribed in Greek uncials: "Morasthi, whence was Micah the prophet." The text is said to have been borrowed from Eusebius' Onomasticon.

- ^ Beside which is inscribed a verse taken from Judges 5:17, "Why did Dan remain in ships?"

- ^ Dalman, Gustaf (2013). Work and Customs in Palestine. I/1. Translated by Nadia Abdulhadi Sukhtian. Ramallah: Dar Al Nasher. p. 65 (note 4). ISBN 9789950385-00-9. OCLC 1040774903.

- ^ Jana Vogt: Architekturmosaiken am Beispiel der drei jordanischen Städte Madaba, Umm al-Rasas und Gerasa. Ernst-Moritz-Arndt-Universität Greifswald, Greifswald 2004

- ^ ARCHEOLOGICAL SITES NO. 5 Jerusalem- the Nea Church and the Cardo

- ^ "Archaeologists find Byzantine era road". CNN. 11 February 2010.

- ^ Dig uncovers ancient Jerusalem street depicted on Byzantine map

- ^ Jerusalem: Architecture in the British Mandate Period

Bibliography[]

Early sources[]

- Abel, F.-M. (1924). "Le Sud Palestinien d'apres la carte mosaique de Madaba". Journal of the Palestine Oriental Society (in French). IV: 107-117.

- Lagrange, M.-J. (July 1897). "JÉRUSALEM D'APRÈS LA MOSAÏQUE DE MADABA". Revue Biblique. Peeters Publishers. 6 (3): 450–458. JSTOR 44101959.

- Palmer, P.; Dr. Guthe (1906), Die Mosaikkarte von Madeba, Im Auftrage des Deutschen Vereins zur Erforschung Palätinas

Later sources[]

- Leal, Beatrice. "A Reconsideration of the Madaba Map." Gesta 57, no. 2 (Fall 2018): 123-143.

- Madden, Andrew M., "A New Form of Evidence to Date the Madaba Map Mosaic," Liber Annuus 62 (2012), 495-513.

- Hepper, Nigel; Taylor, Joan, "Date Palms and Opobalsam in the Madaba Mosaic Map," Palestine Exploration Quarterly, 136,1 (April 2004), 35-44.

- Herbert Donner: The Mosaic Map of Madaba. Kok Pharos Publishing House, Kampen 1992, ISBN 90-390-0011-5

- Herbert Donner; Heinz Cüppers (1977). Die Mosaikkarte von Madeba: Tafelband; Abhandlungen des Deutschen Palästinavereins 5. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 978-3-447-01866-1.

- Avi-Yonah, M.: The Madaba mosaic map. Israel Exploration Society, Jerusalem 1954

- Michele Piccirillo: Chiese e mosaici di Madaba. Studium Biblicum Franciscanum, Collectio maior 34, Jerusalem 1989 (Arabische Edition: Madaba. Kana'is wa fusayfasa', Jerusalem 1993)

- Kenneth Nebenzahl: Maps of the Holy Land, images of Terra Sancta through two millennia. Abbeville Press, New York 1986, ISBN 0-89659-658-3

- Adolf Jacoby: Das geographische Mosaik von Madaba, Die älteste Karte des Heiligen Landes. Dieterich’sche Verlagsbuchhandlung, Leipzig 1905

- Weitzmann, Kurt, ed., Age of spirituality: late antique and early Christian art, third to seventh century, no. 523, 1979, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, ISBN 9780870991790

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Madaba map. |

- Article on the map and its Göttingen copy (in German)1999 (PDF)

- Madaba Map

- The Madaba Mosaic Map at the Franciscan Archaeological Institute

- Madaba Mosaic Map web page at San Francisco State University

- Byzantine Jerusalem and the Madaba Map

- Madaba Map at Bibleplaces.com

- 6th century maps

- History of Jordan

- Medieval Jerusalem

- Byzantine mosaics

- Archaeological discoveries in Jordan

- Old maps of Jerusalem

- Historic maps of the Roman Empire

- 1884 archaeological discoveries

- Maps of Palestine (region)