Major religious groups

Worldwide percentage of adherents by religion, 2015[1]

The world's principal religions and spiritual traditions may be classified into a small number of major groups, though this is not a uniform practice. This theory began in the 18th century with the goal of recognizing the relative levels of civility in different societies,[2] but this practice has since fallen into disrepute in many contemporary cultures.

History of religious categories

The examples and perspective in this article may not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (March 2020) |

In world cultures, there have traditionally been many different groupings of religious belief. In Indian culture, different religious philosophies were traditionally respected as academic differences in pursuit of the same truth. In Islam, the Quran mentions three different categories: Muslims, the People of the Book, and idol worshipers.

Christian categorizations

Initially, Christians had a simple dichotomy of world beliefs: Christian civility versus foreign heresy or barbarity. In the 18th century, "heresy" was clarified to mean Judaism and Islam;[3] along with paganism, this created a fourfold classification which spawned such works as John Toland's Nazarenus, or Jewish, Gentile, and Mahometan Christianity,[4] which represented the three Abrahamic religions as different "nations" or sects within religion itself, the "true monotheism."

Daniel Defoe described the original definition as follows: "Religion is properly the Worship given to God, but 'tis also applied to the Worship of Idols and false Deities."[5] At the turn of the 19th century, in between 1780 and 1810, the language dramatically changed: instead of "religion" being synonymous with spirituality, authors began using the plural, "religions," to refer to both Christianity and other forms of worship. Therefore, Hannah Adams's early encyclopedia, for example, had its name changed from An Alphabetical Compendium of the Various Sects... to A Dictionary of All Religions and Religious Denominations.[6][7]

In 1838, the four-way division of Christianity, Judaism, Mahommedanism (archaic terminology for Islam) and Paganism was multiplied considerably by Josiah Conder's Analytical and Comparative View of All Religions Now Extant among Mankind. Conder's work still adhered to the four-way classification, but in his eye for detail he puts together much historical work to create something resembling the modern Western image: he includes Druze, Yezidis, Mandeans, and Elamites[clarification needed][8] under a list of possibly monotheistic groups, and under the final category, of "polytheism and pantheism," he listed Zoroastrianism, "Vedas, Puranas, Tantras, Reformed sects" of India as well as "Brahminical idolatry," Buddhism, Jainism, Sikhism, Lamaism, "religion of China and Japan," and "illiterate superstitions" as others.[9][10]

The modern meaning of the phrase "world religion," putting non-Christians at the same level as Christians, began with the 1893 Parliament of the World's Religions in Chicago. The Parliament spurred the creation of a dozen privately funded lectures with the intent of informing people of the diversity of religious experience: these lectures funded researchers such as William James, D. T. Suzuki, and Alan Watts, who greatly influenced the public conception of world religions.[11]

In the latter half of the 20th century, the category of "world religion" fell into serious question, especially for drawing parallels between vastly different cultures, and thereby creating an arbitrary separation between the religious and the secular.[12] Even history professors have now taken note of these complications and advise against teaching "world religions" in schools.[13] Others see the shaping of religions in the context of the nation-state as the "invention of traditions."

Classification

This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2014) |

Religious traditions fall into super-groups in comparative religion, arranged by historical origin and mutual influence. Abrahamic religions originate in West Asia,[14][15] Indian religions in the Indian subcontinent (South Asia)[16] and East Asian religions in East Asia.[17] Another group with supra-regional influence are Afro-American religion,[18] which have their origins in Central and West Africa.

- Middle Eastern religions:[19]

- Abrahamic religions are the largest group, and these consist mainly of Judaism, Christianity, Islam, and the Baháʼí Faith. They are named for the patriarch Abraham, and are unified by the practice of monotheism. Today, at least 3.8 billion people are followers of Abrahamic religions[20] and are spread widely around the world apart from the regions around East and Southeast Asia. Several Abrahamic organizations are vigorous proselytizers.[21]

- Iranian religions, partly of Indo-European origins,[22][23] include Zoroastrianism, Yazdânism, Uatsdin, Yarsanism and historical traditions of Gnosticism (Mandaeism, Manichaeism).

- Eastern religions:

- Indian religions, originated in Greater India and they tend to share a number of key concepts, such as dharma, karma, reincarnation among others. They are of the most influence across the Indian subcontinent, East Asia, Southeast Asia, as well as isolated parts of Russia. The main Indian religions are Hinduism, Jainism, Buddhism and Sikhism.

- East Asian religions consist of several East Asian religions which make use of the concept of Tao (in Chinese) or Dō (in Japanese or Korean). They include many Chinese folk religions, Taoism and Confucianism, as well as Korean and Japanese religion influenced by Chinese thought.

- Indigenous ethnic religions, found on every continent, now marginalized by the major organized faiths in many parts of the world or persisting as undercurrents (folk religions) of major religions. Includes traditional African religions, Asian shamanism, Native American religions, Austronesian and Australian Aboriginal traditions, Chinese folk religions, and postwar Shinto. Under more traditional listings, this has been referred to as "paganism" along with historical polytheism.

- African religions:[19]

- The religions of the tribal peoples of Sub-Saharan Africa, but excluding ancient Egyptian religion, which is considered to belong to the ancient Middle East;[19]

- African diasporic religions practiced in the Americas, imported as a result of the Atlantic slave trade of the 16th to 18th centuries, building on traditional religions of Central and West Africa.

- African religions:[19]

- New religious movement is the term applied to any religious faith which has emerged since the 19th century, often syncretizing, re-interpreting or reviving aspects of older traditions such as Ayyavazhi, Mormonism, Ahmadiyya, Pentecostalism, polytheistic reconstructionism, and so forth.

Religious demographics

One way to define a major religion is by the number of current adherents. The population numbers by religion are computed by a combination of census reports and population surveys (in countries where religion data is not collected in census, for example the United States or France), but results can vary widely depending on the way questions are phrased, the definitions of religion used and the bias of the agencies or organizations conducting the survey. Informal or unorganized religions are especially difficult to count.

There is no consensus among researchers as to the best methodology for determining the religiosity profile of the world's population. A number of fundamental aspects are unresolved:

- Whether to count "historically predominant religious culture[s]"[24]

- Whether to count only those who actively "practice" a particular religion[25]

- Whether to count based on a concept of "adherence"[26]

- Whether to count only those who expressly self-identify with a particular denomination[27]

- Whether to count only adults, or to include children as well.

- Whether to rely only on official government-provided statistics[28]

- Whether to use multiple sources and ranges or single "best source(s)"

Largest religious groups

| Religion | Followers (billions) |

Cultural tradition | Founded | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Christianity | 2.4 | Abrahamic religions | Middle East | [29][30] |

| Islam | 1.9 | Abrahamic religions | Arabia (Middle East), 7th century | [31][32] |

| Hinduism | 1.2 | Indian religions | Indian subcontinent | [29] |

| Buddhism | 0.5 | Indian religions | Indian subcontinent | [30] |

| Folk religion | 0.4 | Regional | Worldwide | [33] |

Medium-sized religions

| Religion | Followers (millions) |

Cultural tradition | Founded | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Druze | 1 | Abrahamic religions | Egypt, 9th century | [34] |

| Sikhism | 30 | Indian religions | Indian subcontinent, 15th century | [35] |

| Taoism | 12–173 | Chinese religions | China | [36] |

| Shinto | 100 | Japanese religions | Japan | [37][38] |

| Judaism | 14.5 | Abrahamic religions | The Levant (Middle East) | [29][39] |

| Confucianism | 6–7 | Chinese religions | China | [40] |

| Spiritism | 5-15 | New religious movements | France | [41] |

| Korean shamanism | 5–15 | Korean religions | Korea | [42] |

| Caodaism | 5–9 | Vietnamese religions | Vietnam, 20th century | [43] |

| Baháʼí Faith | 5–7.3 | Abrahamic religions | Iran, 19th century | [44][45][nb 1] |

| Jainism | 4–5 | Indian religions | Indian subcontinent, 7th to 9th century BC | [46][47] |

| Cheondoism | 3–4 | Korean religions | Korea, 19th century | [48] |

| Hoahaoism | 1.5–3 | Vietnamese religions | Vietnam, 20th century | [49] |

| Tenriism | 1.2 | Japanese religions | Japan, 19th century | [50] |

By region

- Religions by country according to The World Factbook - CIA[51]

- Religion by region

- Religion in Africa

- Religion in Antarctica

- Religion in Asia

- Religion in the Middle East

- Muslim world (SW Asia and N Africa)

- Religion in Europe

- Religion in the European Union

- Christian world

- Religion in North America

- Religion in Oceania

- Religion in South America

Trends in adherence

| 1970–1985 (%)[53] | 1990–2000 (%)[54][55] | 2000–2005 (%)[56] | 1970–2010 (%)[45] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baháʼí Faith | 3.65 | 2.28 | 1.70 | 4.26 |

| Buddhism | 1.67 | 1.09 | 2.76 | |

| Christianity | 1.64 | 1.36 | 1.32 | 2.10 |

| Confucianism | 0.83 | |||

| Hinduism | 2.34 | 1.69 | 1.57 | 2.62 |

| Islam | 2.74 | 2.13 | 1.84 | 4.23 |

| Jainism | 2.60 | |||

| Judaism | 1.09 | -0.03 | ||

| Sikhism | 1.87 | 1.62 | 3.08 | |

| Shintoism | -0.83 | |||

| Taoism | 9.85 | |||

| Zoroastrianism | 2.5 | |||

| unaffiliated | 0.37 |

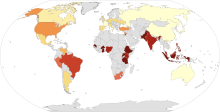

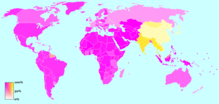

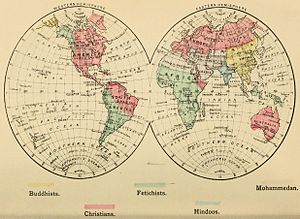

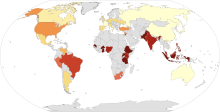

Maps of self-reported adherence

Map showing self-reported religiosity by country. Based on a 2015 worldwide survey by Pew.

World map showing the percentages of people who regard religion as "non-important" according to a 2002 Pew survey

Religions of the world, mapped by distribution.

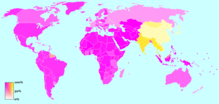

Map showing the prevalence of "Abrahamic religion" (purple), and "Indian religion" (yellow) religions in each country.

Map showing the relative proportion of Christianity (red) and Islam (green) in each country as of 2006

Distribution of world religions by country/state, and by smaller administrative regions for the largest countries (2012 data).% Christian population% Islam population% all other religions but Judaism

Distribution of world religions by country/state, and by smaller administrative regions for the largest countries (2012 data).% Christian population% Islam population% all other religions but Judaism

(Equal parts cyan/magenta - Judaism)

See also

- Irreligion

- List of religions and spiritual traditions

- List of religious populations

- Numinous

- Religious conversion

- State religion

Notes

- ^ Historically, the Baháʼí Faith arose in 19th-century Persia, in the context of Shia Islam, and thus may be classed on this basis as a divergent strand of Islam, placing it in the Abrahamic tradition. However, the Baháʼí Faith considers itself an independent religious tradition, which draws from Islam but also other traditions. The Baháʼí Faith may also be classed as a new religious movement, due to its comparatively recent origin, or may be considered sufficiently old and established for such classification to not be applicable.

References

- ^ Hackett, Conrad; Mcclendon, David (2015). "Christians remain world's largest religious group, but they are declining in Europe". Pew Research Center. Archived from the original on 24 November 2019. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- ^ Masuzawa, Tomoko (2005). The Invention of World Religions. Chicago University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-50989-1.

- ^ Glaser, Daryl; Walker, David M. (12 September 2007). Twentieth-Century Marxism: A Global Introduction. Routledge. ISBN 9781135979744. Archived from the original on 17 December 2019. Retrieved 8 November 2016.

- ^ Toland, John; La Monnoye, Bernard de (1 January 1718). Nazarenus, or, Jewish, gentile, and Mahometan Christianity : containing the history of the antient Gospel of Barnabas, and the modern Gospel of the Mahometans ... also the original plan of Christianity explain'd in the history of the Nazarens ... with the relation of an Irish manuscript of the four Gospels, as likewise a summary of the antient Irish Christianity. London : J. Brotherton, J. Roberts and A. Dodd.

- ^ Masuzawa, Tomoko (26 April 2012). The Invention of World Religions: Or, How European Universalism Was Preserved in the Language of Pluralism. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226922621. Archived from the original on 12 May 2021. Retrieved 27 October 2020.

- ^ Masuzawa 2005. pp. 49–61

- ^ Masuzawa, Tomoko (26 April 2012). The Invention of World Religions: Or, How European Universalism Was Preserved in the Language of Pluralism. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226922621. Archived from the original on 12 May 2021. Retrieved 27 October 2020.

- ^ Masuzawa, Tomoko (26 April 2012). The Invention of World Religions: Or, How European Universalism Was Preserved in the Language of Pluralism. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226922621. Archived from the original on 12 May 2021. Retrieved 27 October 2020.

- ^ Masuzawa 2005, pp. 65–6

- ^ Masuzawa, Tomoko (26 April 2012). The Invention of World Religions: Or, How European Universalism Was Preserved in the Language of Pluralism. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226922621. Archived from the original on 12 May 2021. Retrieved 27 October 2020.

- ^ Masuzawa 2005, 270–281

- ^ Stephen R. L. Clark. "World Religions and World Orders" Archived 8 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Religious studies 26.1 (1990).

- ^ Joel E. Tishken. "Ethnic vs. Evangelical Religions: Beyond Teaching the World Religion Approach" Archived 8 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine. The History Teacher 33.3 (2000).

- ^ Spirituality and Psychiatry - Page 236, Chris Cook, Andrew Powell, A. C. P. Sims - 2009

- ^ "Abraham, Father of the Middle East". www.dangoor.com. Archived from the original on 16 March 2016. Retrieved 8 November 2016.

- ^ "The Religions of the Indian Subcontinent Stretch Back for Millennia". About.com Education. Archived from the original on 25 October 2016. Retrieved 8 November 2016.

- ^ Neusner, Jacob (7 October 2009). World Religions in America, Fourth Edition: An Introduction. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9781611640472. Archived from the original on 12 May 2021. Retrieved 27 October 2020.

- ^ Neusner, Jacob (7 October 2009). World Religions in America, Fourth Edition: An Introduction. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 9781611640472. Archived from the original on 12 May 2021. Retrieved 27 October 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "classification of religions | Principles & Significance". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 14 December 2007. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- ^ Statistician, Howard Steven Friedman; Teacher, health economist for the United Nations; University, Columbia (25 April 2011). "5 Religions with the Most Followers | Huffington Post". The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on 8 December 2016. Retrieved 8 November 2016.

- ^ Brodd, Jeffrey (2003). World Religions. Winona, Minnesota: Saint Mary's Press. ISBN 978-0-88489-725-5.

- ^ Samuel 2010.

- ^ Anthony 2007.

- ^ Pippa Norris; Ronald Inglehart (6 January 2007), Sacred and Secular, Religion and Politics Worldwide, Cambridge University Press, pp. 43–44, archived from the original on 12 May 2021, retrieved 29 December 2006

- ^ Pew Research Center (19 December 2002). "Among Wealthy Nations U.S. Stands Alone in its Embrace of Religion". Pew Research Center. Archived from the original on 21 August 2011. Retrieved 12 October 2006.

- ^ adherents.com (28 August 2005). "Major Religions of the World Ranked by Number of Adherents". adherents.com. Archived from the original on 15 June 2008. Retrieved 12 October 2006.CS1 maint: unfit URL (link)

- ^ worldvaluessurvey.org (28 June 2005). "World Values Survey". worldvaluessurvey.org. Archived from the original on 14 April 2014. Retrieved 12 October 2006.

- ^ unstats.un.org (6 January 2007). "United Nations Statistics Division - Demographic and Social Statistics". United Nations Statistics Division. Archived from the original on 10 January 2007. Retrieved 6 January 2007.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "The Global Religious Landscape". The Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life. Pew Research center. 18 December 2012. Archived from the original on 25 December 2018. Retrieved 18 March 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Christianity 2015: Religious Diversity and Personal Contact" (PDF). gordonconwell.edu. January 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 May 2017. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- ^ "Christianity 2015: Religious Diversity and Personal Contact" (PDF). gordonconwell.edu. January 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 May 2017. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- ^ "Why Muslims are the world's fastest-growing religious group". Pew Research Center. 6 April 2017. Archived from the original on 23 August 2017. Retrieved 11 May 2017.

- ^ "Folk Religionists". pewforum.org. Pew Research Center. December 2012. Archived from the original on 31 July 2013. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- ^ "Druze | History, Religion, & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 16 June 2021.

- ^ "Sikhism". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 29 December 2019. Retrieved 7 August 2017.

- ^ 2010 Chinese Spiritual Life Survey conducted by the Purdue University's Center on Religion and Chinese Society. Statistics published in: Katharina Wenzel-Teuber, David Strait. People's Republic of China: Religions and Churches Statistical Overview 2011 Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine. On: Religions & Christianity in Today's China, Vol. II, 2012, No. 3, pp. 29-54, ISSN 2192-9289.

- ^ "Major Religions Ranked by Size". Adherents.com. Archived from the original on 15 June 2008. Retrieved 24 June 2010.CS1 maint: unfit URL (link)

- ^ "Japan: International Religious Freedom Report 2006". Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor; U.S. Department of State. 15 September 2006. Archived from the original on 12 May 2021. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- ^ "Jewish Population of the World". www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Archived from the original on 24 January 2017. Retrieved 18 December 2018.

- ^ Johnson, Todd M.; Grim, Brian J. (2013). The World's Religions in Figures: An Introduction to International Religious Demography (PDF). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell. p. 10. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 October 2013. Retrieved 24 November 2015.

- ^ "Tabela 2102: População residente por situação do domicílio, religião e sexo". sidra.ibge.gov.br. Archived from the original on 27 February 2021. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- ^ Self-reported figures from 1999; North Korea only (South Korean followers are minimal according to census). In The A to Z of New Religious Movements by George D. Chryssides. ISBN 0-8108-5588-7.

- ^ Sergei Blagov. "Caodaism in Vietnam : Religion vs Restrictions and Persecution Archived 9 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine". IARF World Congress, Vancouver, Canada, July 31, 1999.

- ^ Other Religions Archived 19 July 2019 at the Wayback Machine. Pew Forum report.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Grim, Brian J (2012). "Rising restrictions on religion" (PDF). International Journal of Religious Freedom. 5 (1): 17–33. ISSN 2070-5484. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 July 2013. Retrieved 25 April 2013.

- ^ Voorst 2014, p. 96.

- ^ "Jainism". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 26 July 2017. Retrieved 7 August 2017.

- ^ Self-reported figures from North Korea (South Korean followers are minimal according to census): "Religious Intelligence UK report". Religious Intelligence. Religious Intelligence. Archived from the original on 13 October 2007. Retrieved 4 July 2009.

- ^ Janet Alison Hoskins. What Are Vietnam's Indigenous Religions? Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Center for Southeast Asian Studies Kyoto University.

- ^ "宗教年鑑" [Yearly Report on Religion] (PDF) (in Japanese). Agency for Cultural Affairs. 2019. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 December 2020. Retrieved 2 December 2020.

- ^ "The World Factbook – Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov. Archived from the original on 12 December 2016. Retrieved 8 November 2016.

- ^ The results have been studied and found "highly correlated with other sources of data", but "consistently gave a higher estimate for percent Christian in comparison to other cross-national data sets." Hsu, Becky; Reynolds, Amy; Hackett, Conrad; Gibbon, James (9 July 2008). "Estimating the Religious Composition of All Nations". Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 47 (4): 678. doi:10.1111/j.1468-5906.2008.00435.x.

- ^ International Community, Baháʼí (1992). "How many Baháʼís are there?". The Baháʼís. p. 14. Archived from the original on 22 May 2011. Retrieved 10 August 2008..

- ^ Barrett, David A. (2001). World Christian Encyclopedia. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-19-507963-0. Archived from the original on 20 October 2017. Retrieved 12 October 2007.

- ^ Barrett, David; Johnson, Todd (2001). "Global adherents of the World's 19 distinct major religions" (PDF). William Carey Library. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 February 2008. Retrieved 12 October 2006.

- ^ Staff (May 2007). "The List: The World's Fastest-Growing Religions". Foreign Policy. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Archived from the original on 25 January 2010. Retrieved 25 December 2013.

Sources

- Anthony, David W. (2007), The Horse, the Wheel and Language: how Bronze-Age riders from the Eurasian Steppes shaped the modern world, Princeton University Press

- Doniger, Wendy, ed. (2006). Britannica Encyclopedia of World Religions. Encyclopaedia Britannica. ISBN 978-1593392666.

- Samuel, Geoffrey (2010), The Origins of Yoga and Tantra: Indic Religions to the Thirteenth Century, Cambridge University Press

- Voorst, Robert E. Van (2014), RELG: World (2 ed.), Cengage Learning, ISBN 978-1-285-43468-1 [1]

External links

- Animated history of World Religions—from the "Religion & Ethics" part of the BBC website, interactive animated view of the spread of world religions (requires Flash plug-in).

- BBC A-Z of Religions and Beliefs

- Major World Religions

- International Council for Inter-Religious Cooperation

- ^ Voorst 2014, p. 111.

- Religion-related lists

- Religious demographics