Malayan tapir

| Malayan tapir | |

|---|---|

| |

| Malayan tapir at Tiergarten Nürnberg in Nuremberg, Germany | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Perissodactyla |

| Family: | Tapiridae |

| Genus: | Acrocodia |

| Species: | A. indica

|

| Binomial name | |

| Acrocodia indica | |

| |

| Malayan tapir range | |

| Synonyms[3] | |

| |

The Malayan tapir (Acrocodia indica), also called the Asian tapir, Asiatic tapir, Oriental tapir, Indian tapir, or piebald tapir, is the largest of the four widely-recognized species of tapir, and the only one native to the Old World.[4] The scientific name refers to the East Indies, the species' natural habitat. In the Malay language, it is commonly referred to as cipan, tenuk or badak tampung.[5]

Taxonomy[]

The species was formerly included with all other extant tapir species in the genus Tapirus, but was later reassigned to the separate genus Acrocodia.[6]

Description[]

The Malayan Tapir is easily identified by its markings, most notably the light-colored patch that extends from its shoulders to its hindquarters. It is covered in black hair, except for the tips of its ears, which, as with other tapirs, are rimmed with white. The pattern is for camouflage; the disrupted coloration breaks up its outline and makes it more difficult to recognize; other animals may mistake it for a large rock, rather than prey, when it is lying down to sleep.[7]

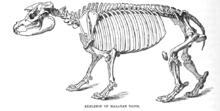

The Malayan tapir grows to between 1.8 and 2.5 m (5 ft 11 in and 8 ft 2 in) in length, not counting a stubby tail of only 5 to 10 cm (2.0 to 3.9 in) in length, and stands 90 to 110 cm (2 ft 11 in to 3 ft 7 in) tall. It typically weighs between 250 and 320 kg (550 and 710 lb), although some adults can weigh up to 540 kg (1,190 lb).[8][9][10][11] The females are usually larger than the males. Like other tapir species, it has a small, stubby tail and a long, flexible proboscis. It has four toes on each front foot and three toes on each back foot. The Malayan tapir has rather poor eyesight, but excellent hearing and sense of smell.

It has a large sagittal crest, a bone running along the middle of the skull that is necessary for muscle attachment. It also possesses unusually positioned orbits, an unusually shaped cranium with the frontal bones elevated, and a retracted nasal incision. All of these modifications to the normal mammal skull are, of course, to make room for the proboscis. This proboscis caused a retraction of bones and cartilage in the face during the evolution of the tapir, and even caused the loss of some cartilages, facial muscles, and the bony wall of the nasal chamber.

Vision[]

Malayan tapirs have very poor eyesight, making them rely greatly on their excellent sense of smell and hearing to go about in their everyday lives. They have small, beady eyes with brown irises on either side of their faces. Their eyes are often covered in a blue haze, which is corneal cloudiness thought to be caused by repetitive exposure to light. Corneal cloudiness is a condition in which the cornea starts to lose its transparency. The cornea is necessary for the transmitting and focusing of outside light as it enters the eye, and cloudiness can cause vision loss. This causes the Malayan tapir to have very inadequate vision, both on land and in water, where they spend the majority of their time. Also, as these tapirs are most active at night and since they have poor eyesight, it is harder for them to search for food and avoid predators in the dark.[12][13]

A. i. brevetianus variation[]

A small number of melanistic (all-black) Malayan tapirs have been observed. In 1924, an all-black tapir was sent to Rotterdam Zoo and was classified as a subspecies called Acrocodia indica brevetianus after its discoverer, Captain K. Brevet.[14] In 2000, two melanistic tapirs were observed during a study of tigers in the Jerangau Forest Reserve in Malaysia.[15] The cause of this variation may be a genetic abnormality similar to that of black panthers that appear in populations of spotted leopards or spotted jaguars. However, unless, and until, more A. i. brevetianus individuals can be studied, the precise explanation for the trait will remain unknown.

Lifecycle[]

The gestation period of the Malayan tapir is about 390–395 days, after which a single offspring, weighing around 15 pounds (6.8 kg), is born. Malayan tapirs are the largest of the four tapir species at birth and in general, and grow more quickly than their relatives.[16] Young tapirs of all species have brown hair with white stripes and spots, a pattern that enables them to hide effectively in the of the forest. This baby coat fades into adult coloration between four and seven months after birth. Weaning occurs between six and eight months of age, at which time the babies are nearly full-grown, and the animals reach sexual maturity around age three. Breeding typically occurs in April, May or June, and females generally produce one calf every two years. Malayan tapirs can live up to 30 years, both in the wild and in captivity.

Behavior[]

Malayan tapirs are primarily solitary creatures, marking out large tracts of land as their territory, though these areas usually overlap with those of other individuals. Tapirs mark out their territories by spraying urine on plants, and they often follow distinct paths, which they have bulldozed through the undergrowth.[citation needed]

Exclusively herbivorous, the animal forages for the tender shoots and leaves of more than 115 species of plants (around 30 are particularly preferred), moving slowly through the forest and pausing often to eat and note the scents left behind by other tapirs in the area.[5] However, when threatened or frightened, the tapir can run quickly, despite its considerable bulk, and can also defend itself with its strong jaws and sharp teeth. Malayan tapirs communicate with high-pitched squeaks and whistles. They usually prefer to live near water and often bathe and swim, and they are also able to climb steep slopes. Tapirs are mainly active at night, though they are not exclusively nocturnal. They tend to eat soon after sunset or before sunrise, and they will often nap in the middle of the night. This behavior characterizes them as crepuscular animals.

Habitat, predation, and vulnerability[]

The Malayan tapir is found throughout the tropical lowland rainforests of Southeast Asia, including Sumatra in Indonesia, Peninsular Malaysia, Myanmar, and Thailand. Populations in Sabah in Borneo may have persisted until recently but are now considered extinct.[17] Current populations have decreased in recent years, and today, like all tapirs, it is in danger of extinction.[1] Because of their size, tapirs have few natural predators, and even reports of killings by tigers (Panthera tigris), leopards (Panthera pardus), or dholes (Cuon alpinus) are scarce.[18] The main threat to the Malayan tapirs is human activity, including deforestation for agricultural purposes, flooding caused by the damming of rivers for hydroelectric projects, and illegal trade.[19] In Thailand, for instance, capture and sale of a young tapir may be worth US$5500.00.[18] In areas such as Sumatra, where the population is predominantly Muslim, tapirs are seldom hunted for food due to their physical similarity to pigs. But in some regions they are hunted for sport or shot accidentally when mistaken for other animals.[20] Protected status in Malaysia, Indonesia, and Thailand, which seeks to curb deliberate killing of tapirs but does not address the issue of habitat loss, has had limited effect in reviving or maintaining the population.

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Traeholt, C.; Novarino, W.; bin Saaban, S.; Shwe, N.M.; Lynam, A.; Zainuddin, Z.; Simpson, B. & bin Mohd, S. (2016). "Tapirus indicus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T21472A45173636. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- ^ "Tapir l'inde, Tapirus indicus". Nouveau dictionnaire d'histoire naturelle. Paris: Deterville. 1819. p. 458.

- ^ "Acrocodia indica (Desmarest, 1819)". Species 2000 & ITIS Catalogue of Life. Species 2000: Naturalis, Leiden, the Netherlands. Retrieved 9 March 2021.

- ^ Grubb, P. (2005). "Order Perissodactyla". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 633. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ Jump up to: a b bin Momin Khan, Mohd Khan. "Status and Action Plan of the Malayan Tapir (Tapirus indicus)" Tapirs: Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan published by IUCN Tapir Specialist Group, 1997, page 1

- ^ Groves, C.; Grubb, P (2011). Ungulate taxonomy. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 18.

- ^ "Woodland Park Zoo Animal Fact Sheet: Malayan Tapir (Tapirus indicus)". Archived from the original on September 24, 2006.

- ^ Wilson & Burnie, Animal: The Definitive Visual Guide to the World's Wildlife. DK ADULT (2001), ISBN 978-0-7894-7764-4

- ^ Tapirus indicus, Animal Diversity Web

- ^ Asian Tapir Archived 2014-12-21 at the Wayback Machine,|Arkive

- ^ "Malayan tapir". www.ultimateungulate.com.

- ^ "Cambridge Journals Online - Abstract". Journals.cambridge.org. 2001-02-27. Retrieved 2011-01-15.

- ^ "Tapirus terrestris (lowland tapir)". Digimorph. 2002-02-08. Retrieved 2011-01-15.

- ^ Shuker, Dr. Karl P. N. Mysteries of Planet Earth, pages 11-12

- ^ Mohd, Azlan J. "Recent Observations of Melanistic Tapirs in Peninsular Malaysia" Archived 2006-06-25 at the Wayback Machine. Tapir Conservation: The Newsletter of the IUCN/SSC Tapir Specialist Group, June 2002, Volume 11, Number 1, pages 27-28

- ^ Fahey, B. 1999. "Tapirus indicus" (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved June 16, 2006.

- ^ Cranbrook, E. O.; Piper, P. J. (2009). "Borneo records of Malay tapir, Tapirus indicus Desmarest: a zooarchaeological and historical review". International Journal of Osteoarchaeology. 19 (4): 491–507. doi:10.1002/oa.1015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b bin Momin Khan, Mohd Khan. "Status and Action Plan of the Malayan Tapir (Tapirus indicus)" Tapirs: Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan published by IUCN Tapir Specialist Group, 1997, page 2

- ^ Fact sheet on Malayan Tapir - Tapirus indicus Archived 2008-04-09 at the Wayback Machine, UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre, in association with the World Wildlife Foundation

- ^ Simon, Tamar. "The Tapir: A Big Unknown" article from Discovery Channel Canadian website Archived 2001-07-11 at the Wayback Machine, July 22, 1999.

External links[]

Media related to Tapirus indicus at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Tapirus indicus at Wikimedia Commons- ARKive - images and movies of the Asian tapir (Tapirus indicus)

- Tapir Specialist Group - Malayan Tapir

- IUCN Red List endangered species

- Tapirs

- Fauna of Southeast Asia

- Mammals of Malaysia

- Mammals of Indonesia

- Mammals of Myanmar

- Mammals of Thailand

- Endangered fauna of Asia

- EDGE species

- Mammals described in 1819