Malcolm Cecil

Malcolm Cecil | |

|---|---|

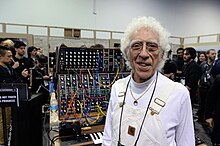

Cecil in 2015 | |

| Background information | |

| Born | 9 January 1937 London, England |

| Died | 28 March 2021 (aged 84) |

| Genres |

|

| Occupation(s) |

|

| Instruments |

|

| Associated acts | |

Malcolm Cecil (9 January 1937 – 28 March 2021) was a British jazz bassist, record producer, engineer and electronic musician. He was a founding member of a leading UK jazz quintet of the late 1950s, the Jazz Couriers,[1] before going on to join a number of British jazz combos led by Dick Morrissey, Tony Crombie and Ronnie Scott in the late 1950s and early 1960s.[2] He later joined Cyril Davies and Alexis Korner to form the original line-up of Blues Incorporated. Cecil subsequently collaborated with Robert Margouleff to form the duo TONTO's Expanding Head Band, a project based on a unique combination of synthesizers which led to them collaborating on and co-producing several of Stevie Wonder's Grammy-winning albums of the early 1970s.[3] The TONTO synthesizer was described by Rolling Stone as "revolutionary".

Early life[]

Cecil was born in London on 9 January 1937. He became a radio ham by the age of nine. He worked as an engineer in the Royal Air Force during the time that he was learning to be a professional jazz musician. He became a member of Ronnie Scott's group during his 20s, before changing styles and becoming one of the founders of Blues Incorporated.[4]

Cecil moved to South Africa before relocating to San Francisco in the mid-1960s. After a stint at the Los Angeles recording studio of Pat Boone, Cecil settled in New York City and began to modulate.[4]

Career[]

With Robert Margouleff, Cecil formed the duo TONTO's Expanding Head Band, a synthesizer-based project. The duo were closely associated with Stevie Wonder's Talking Book (1972), sharing the Best Engineered Album, Non-Classical award as well as collaborating on and co-producing classic Wonder albums such as Music of My Mind, Innervisions and Fulfillingness' First Finale.[5][6] Cecil is credited, with Margouleff, as engineer for the Stevie Wonder-produced album Perfect Angel (1974), by Minnie Riperton.[7]

Cecil and Margouleff began constructing the "The Original New Timbral Orchestra" (TONTO) in 1968.[4] It became the largest analog synthesizer,[8][9] as well as the most advanced one at the time. It had a height of 6 feet (1.8 m), a maximum diameter of 25 feet (7.6 m), and a mass of one ton.[10] The synthesizer made its debut in the pair's album Zero Time (1971).[4] Their unique sound made them highly sought-after and they went on to collaborate with, amongst others, Quincy Jones,[4] Bobby Womack,[8] the Isley Brothers,[4] Billy Preston,[9] Gil Scott-Heron, Weather Report,[8] Stephen Stills,[9] the Doobie Brothers,[8] Dave Mason,[10] Little Feat,[8] Joan Baez,[4] and Steve Hillage.[7] TONTO also appeared in Phantom of the Paradise (1974), although Cecil was reportedly incensed because he had not approved of its use in the film.[4]

The vocalist Gil Scott-Heron, who wrote that he considered Cecil a creative genius,[11] along with keyboardist Brian Jackson enlisted Cecil and his TONTO synthesizer for the production of their collaborative album, 1980. Scott-Heron and Jackson were featured on the album cover with the synthesizer.[12] TONTO was described as "revolutionary" by Rolling Stone, but it eventually fell behind more modern synthesizers that were simpler to utilize.[8]

Later life[]

Cecil sold TONTO in 2013 to the National Music Centre in Calgary.[10] Through , the museum finished a complete restoration of the synthesiser five years later, with Leimseider dying shortly afterwards.[10][13] TONTO continued to be on display there at the time of Cecil's death.[9]

Cecil died on 28 March 2021. He was 84 and suffered from an unspecified long illness prior to his death.[14][15]

Honours and recognition[]

Cecil was nominated for and won a Grammy Award in 1973 for best engineered recording – non-classical. This was in recognition for the work he did with Margouleff on Wonder's Innervisions.[14][16] Cecil was later bestowed the Unsung Hero award for lifetime achievement by Q magazine in 1997.[14]

Discography[]

- As leader/co-leader

Solo[]

With TONTO's Expanding Headband[]

- As sideman

- 1961: It's Morrissey, Man! – Dick Morrissey Quartet[19]

- 1961: The Tony Crombie Orchestra[20]

- 1961: Let's Take Five – Emcee Five[21]

- 1962: Bebop from the East Coast – Emcee Five[22]

- 1971: Where Would I Be? – Jim Hall Trio[7]

- 1973: 3+3 – The Isley Brothers[7]

- 1974: Live It Up – The Isley Brothers[7]

- 1975: The Heat Is On – The Isley Brothers[7]

- 1976: Harvest for the World – The Isley Brothers[7]

- 1978: Secrets – Gil Scott-Heron (with Brian Jackson)[7]

- 1980: 1980 – Gil Scott-Heron (with Brian Jackson)[7]

- 1980: Real Eyes – Gil Scott-Heron[7]

- 1981: Reflections – Gil Scott-Heron[7]

- 1982: Moving Target – Gil Scott-Heron[7]

- 1983: Shut 'Um Down; Angel Dust (singles) – Gil Scott-Heron[23]

- 1994: Spirits – Gil Scott-Heron[7]

- 1996: A Jazzy Christmas – Bill Augustine[7]

- 2009: A Jazzy Christmas 2 – Bill Augustine[7]

- 2011: We're New Here – Gil Scott-Heron (with Jamie xx)[7]

Production, programming, and/or engineering[]

As producer, programmer, and/or engineer:[24]

With Stevie Wonder[]

- 1972: Music of My Mind[7]

- 1972: Talking Book[7]

- 1973: Innervisions[7]

- 1974: Fulfillingness' First Finale[7]

- 1991: Jungle Fever[7]

Various[]

- Dave Mason – It's Like You Never Left (1973)[7]

- Mandrill – Beast From The East (1975)[25]

- Billy Preston – It's My Pleasure (1975)[7]

- Billy Preston – Billy Preston (1976)[7]

- Steve Hillage – Motivation Radio (1977)[7]

- Savoy Brown – Kings of Boogie (1989 – recording engineer)[7]

- Neil Norman – Greatest Science Fiction Hits lV (1998)[7]

- Pete Bardens – Watercolours (2002)[7]

References[]

- ^ The Jazz Couriers at David Taylor's British jazz web site Archived 8 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Ronnie Scott at David Taylor's British jazz web site Archived 26 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Holmes, Thom (2015). Electronic and Experimental Music: Technology, Music, and Culture. Routledge. ISBN 9781317410232.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h Roberts, Randall (29 March 2021). "Malcolm Cecil, synthesizer pioneer and Stevie Wonder collaborator, dies at 84". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2 April 2021.

- ^ Betts, Graham (2014). Motown Encyclopedia. AC Publishing. ISBN 9781311441546.

- ^ The Mojo Collection (4th ed.). Canongate Books. 2007. ISBN 9781847676436.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae "Malcolm Cecil – Credits". AllMusic. Retrieved 29 March 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Blistein, Jon (29 March 2021). "Malcolm Cecil, Producer for Stevie Wonder and Co-Creator of Revolutionary TONTO Synth, Dead at 84". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 2 April 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Irwin, Corey (28 March 2021). "Malcolm Cecil, Stevie Wonder Producer, Dies at 84". Ultimate Classic Rock. Retrieved 2 April 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Porter, Martin; Goggin, David (13 November 2018). "TONTO: The 50-Year Saga of the Synth Heard on Stevie Wonder Classics". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 2 April 2021.

- ^ Scott-Heron, Gil (2011). Now and Then. Canongate Books. ISBN 9781847677440.

- ^ Suskind, Alex (11 June 2013). "Gil Scott-Heron & Brian Jackson". Wax Poetics. Retrieved 22 December 2018.

- ^ Hussey, Allison (28 March 2021). "Malcolm Cecil, Synth Pioneer and Stevie Wonder Producer, Dies at 84". Pitchfork. Retrieved 2 April 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Brandle, Lars (29 March 2021). "Malcolm Cecil, Synth Pioneer and Stevie Wonder Collaborator, Dies at 84". Billboard. Retrieved 2 April 2021.

- ^ "Malcolm Cecil, influential producer and Stevie Wonder collaborator, has died". 29 March 2021.

- ^ "16th Annual Grammy Awards (1973)". The Recording Academy. Retrieved 2 April 2021.

- ^ Rideout, Ernie, ed. (2011). Keyboard Presents Synth Gods. Berklee Press. p. 27. ISBN 9780879309992.

- ^ Domanick, Andrea (12 February 2020). "Best concerts in L.A. this week: Courtney Barnett, Mac DeMarco, Ginuwine". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 1 April 2021.

- ^ Cook, Richard; Morton, Brian (2002). The Penguin Guide to Jazz on CD. Penguin Books. p. 1073. ISBN 9780140515213.

- ^ Lord, Tom (1992). The Jazz Discography. 4. Lord Music Reference. p. C-713. ISBN 9781881993032.

- ^ Gramophone. 40. General Gramophone Publications Limited. 1962. p. 36.

- ^ "Bebop from the East Coast 1960/1962". BBC Music Magazine. 20 January 2012. Retrieved 1 April 2021.

- ^ Jones, Jackie (25 June 2007). "20 People Who Changed Black Music – Revolutionary Poet Gil Scott-Heron, the First Rap Rebel". Miami Herald. Retrieved 1 April 2021.

- ^ "Malcolm Cecil – Discogs". discogs. Retrieved 27 November 2014.

- ^ "Malcolm Cecil – Discography". TONTO Studio. Retrieved 1 April 2021.

External links[]

- Malcolm Cecil discography at Discogs

- Malcolm Cecil at IMDb

- Malcolm Cecil NAMM Oral History Interview (2016)

- Malcolm Cecil obituary in New York Times (2021)

- 1937 births

- 2021 deaths

- English record producers

- English composers

- British jazz bass guitarists

- Musicians from London

- Blues Incorporated members