Mark the Evangelist

Saint Mark the Evangelist | |

|---|---|

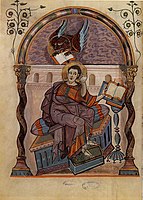

Miniature of Saint Mark from the Grandes Heures of Anne of Brittany (1503–1508) by Jean Bourdichon | |

| Evangelist, Martyr | |

| Born | 5 AD Cyrene, Pentapolis of North Africa, according to Coptic tradition[1] |

| Died | 25 April 68 (aged 62–63) Alexandria, Egypt, Roman Empire |

| Venerated in | All Christian churches that venerate saints |

| Major shrine | St Mark's Basilica, Saint Mark's Coptic Orthodox Cathedral (Alexandria) |

| Feast |

|

| Patronage | Barristers, Venice,[2] Egypt, Mainar |

| Major works | Gospel of Mark |

Mark the Evangelist (Latin: Marcus; Greek: Μᾶρκος, romanized: Mârkos; Aramaic: ܡܪܩܘܣ Marqōs) is the traditionally ascribed author of the Gospel of Mark. Mark is said to have founded the Church of Alexandria, one of the most important episcopal sees of early Christianity. His feast day is celebrated on April 25, and his symbol is the winged lion.[3]

Mark's identity[]

According to William Lane (1974), an "unbroken tradition" identifies Mark the Evangelist with John Mark,[4] and John Mark as the cousin of Barnabas.[5] However, Hippolytus of Rome in On the Seventy Apostles distinguishes Mark the Evangelist (2 Tim 4:11), John Mark (Acts 12:12, 25; 13:5, 13; 15:37), and Mark the cousin of Barnabas (Col 4:10; Phlm 1:24).[6] According to Hippolytus, they all belonged to the "Seventy Disciples" who were sent out by Jesus to disseminate the gospel (Luke 10:1ff.) in Judea.

According to Eusebius of Caesarea (Eccl. Hist. 2.9.1–4), Herod Agrippa I, in his first year of reign over the whole of Judea (AD 41), killed James, son of Zebedee and arrested Peter, planning to kill him after the Passover. Peter was saved miraculously by angels, and escaped out of the realm of Herod (Acts 12:1–19). Peter went to Antioch, then through Asia Minor (visiting the churches in Pontus, Galatia, Cappadocia, Asia, and Bithynia, as mentioned in 1 Peter 1:1), and arrived in Rome in the second year of Emperor Claudius (AD 42; Eusebius, Eccl, Hist. 2.14.6). Somewhere on the way, Peter encountered Mark and took him as travel companion and interpreter. Mark the Evangelist wrote down the sermons of Peter, thus composing the Gospel according to Mark (Eccl. Hist. 15–16), before he left for Alexandria in the third year of Claudius (AD 43).[7]

According to the Acts 15:39, Mark went to Cyprus with Barnabas after the Council of Jerusalem.

According to tradition, in AD 49, about 19 years after the Ascension of Jesus, Mark travelled to Alexandria and founded the Church of Alexandria – today, the Coptic Orthodox Church, the Greek Orthodox Church of Alexandria, and the Coptic Catholic Church trace their origins to this original community.[8] Aspects of the Coptic liturgy can be traced back to Mark himself.[9] He became the first bishop of Alexandria and he is honored as the founder of Christianity in Africa.[10]

According to Eusebius (Eccl. Hist. 2.24.1), Mark was succeeded by Anianus as the bishop of Alexandria in the eighth year of Nero (62/63), probably, but not definitely, due to his coming death. Later Coptic tradition says that he was martyred in 68.[1][11][12][13][14]

Modern mainstream Bible scholars argue the Gospel of Mark was written by an anonymous author, rather than direct witnesses to the reported events.[15][16][17][18][19]

Biblical and traditional information[]

Evidence for Mark the Evangelist's authorship of the Gospel that bears his name originates with Papias.[20][21] Scholars of the Trinity Evangelical Divinity School are "almost certain" that Papias is referencing John Mark.[22] Modern mainstream Bible scholars discard Papias's information as unreliable.[23] Eusebius had a "low esteem of Papias' intellect".[24]

Identifying Mark the Evangelist with John Mark also led to identifying him as the man who carried water to the house where the Last Supper took place (Mark 14:13),[25] or as the young man who ran away naked when Jesus was arrested (Mark 14:51–52).[26]

The Coptic Church accords with identifying Mark the Evangelist with John Mark, as well as that he was one of the Seventy Disciples sent out by Christ (Luke 10:1), as Hippolytus confirmed.[27] Coptic tradition also holds that Mark the Evangelist hosted the disciples in his house after Jesus's death, that the resurrected Jesus Christ came to Mark's house (John 20), and that the Holy Spirit descended on the disciples at Pentecost in the same house.[27] Furthermore, Mark is also believed to have been among the servants at the Marriage at Cana who poured out the water that Jesus turned to wine (John 2:1–11).[27]

According to the Coptic tradition, Mark was born in Cyrene, a city in the Pentapolis of North Africa (now Libya). This tradition adds that Mark returned to Pentapolis later in life, after being sent by Paul to Colossae (Colossians 4:10; Philemon 24. Some, however, think these actually refer to Mark the Cousin of Barnabas), and serving with him in Rome (2 Tim 4:11); from Pentapolis he made his way to Alexandria.[28][29] When Mark returned to Alexandria, the pagans of the city resented his efforts to turn the Alexandrians away from the worship of their traditional gods.[citation needed] In AD 68, they placed a rope around his neck and dragged him through the streets until he was dead.[30]

Veneration[]

The Feast of St Mark is observed on April 25 by the Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Churches. For those Churches still using the Julian Calendar, April 25 according to it aligns with May 8 on the Gregorian Calendar until the year 2099. The Coptic Orthodox Church observes the Feast of St Mark on Parmouti 30 according to the Coptic Calendar which always aligns with April 25 on the Julian Calendar or May 8 on the Gregorian Calendar.

Where John Mark is distinguished from Mark the Evangelist, John Mark is celebrated on September 27 (as in the Roman Martyrology) and Mark the Evangelist on April 25.

Mark is remembered in the Church of England and in much of the Anglican Communion, with a Festival on 25 April.[31]

Relics of Saint Mark[]

In 828, relics believed to be the body of Saint Mark were taken from Alexandria (at the time controlled by the Abbasid Caliphate) by two Venetian merchants with the help of two Greek monks and taken to Venice.[32] A mosaic in St Mark's Basilica depicts sailors covering the relics with a layer of pork and cabbage leaves. Since Muslims are not permitted to eat pork, this was done to prevent the guards from inspecting the ship's cargo too closely.[33]

Donald Nicol explained this act as "motivated as much by politics as by piety", and "a calculated stab at the pretensions of the Patriarchate of Aquileia." Instead of being used to adorn the church of Grado, which claimed to possess the throne of Saint Mark, it was kept secretly by Doge Giustiniano Participazio in his modest palace. Possession of Saint Mark's remains was, in Nicol's words, "the symbol not of the Patriarchate of Grado, nor of the bishopric of Olivolo, but of the city of Venice." In his will, Doge Giustiniano asked his widow to build a basilica dedicated to Saint Mark, which was erected between the palace and the chapel of Saint Theodore Stratelates, who until then had been patron saint of Venice.[34]

In 1063, during the construction of St Mark's Basilica in Venice, Saint Mark's relics could not be found. However, according to tradition, in 1094, the saint himself revealed the location of his remains by extending an arm from a pillar.[35] The newfound remains were placed in a sarcophagus in the basilica.[36]

Copts believe that the head of Saint Mark remains in a church named after him in Alexandria, and parts of his relics are in Saint Mark's Coptic Orthodox Cathedral, Cairo. The rest of his relics are in Venice.[1] Every year, on the 30th day of the month of Paopi, the Coptic Orthodox Church celebrates the commemoration of the consecration of the church of Saint Mark, and the appearance of the head of the saint in the city of Alexandria. This takes place inside St Mark's Coptic Orthodox Cathedral in Alexandria.[37]

In June 1968, Pope Cyril VI of Alexandria sent an official delegation to Rome to receive a relic of Saint Mark from Pope Paul VI. The delegation consisted of ten metropolitans and bishops, seven of whom were Coptic and three Ethiopian, and three prominent Coptic lay leaders.

The relic was said to be a small piece of bone that had been given to the Roman pope by Giovanni Cardinal Urbani, Patriarch of Venice. Pope Paul, in an address to the delegation, said that the rest of the relics of the saint remained in Venice.

The delegation received the relic on June 22, 1968. The next day, the delegation celebrated a pontifical liturgy in the Church of Saint Athanasius the Apostolic in Rome. The metropolitans, bishops, and priests of the delegation all served in the liturgy. Members of the Roman papal delegation, Copts who lived in Rome, newspaper and news agency reporters, and many foreign dignitaries attended the liturgy.

In art[]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2018) |

Mark the Evangelist is most often depicted writing or holding his gospel.[38] In Christian tradition, Mark the Evangelist is symbolized by a lion.[39]

Mark the Evangelist attributes are the lion in the desert; he can be depicted as a bishop on a throne decorated with lions; as a man helping Venetian sailors. He is often depicted holding a book with pax tibi Marce written on it or holding a palm and book. Other depictions of Mark show him as a man with a book or scroll, accompanied by a winged lion. The lion might also be associated with Jesus' Resurrection because lions were believed to sleep with open eyes, thus a comparison with Christ in his tomb, and Christ as king.

Mark the Evangelist can be depicted as a man with a halter around his neck and as rescuing Christian slaves from Saracens.

- Depictions of Mark the Evangelist

Venetian merchants with the help of two Greek monks take Mark the Evangelist's body to Venice, by Tintoretto.

Mark the Evangelist listening to the winged lion, Mark, image 21 of the Codex Aureus of Lorsch or Borsch Gospels.

Mark the Evangelist looking at the lion, c.823.

The martyrdom of Saint Mark. Très Riches Heures du duc de Berry (Musée Condé, Chantilly), c. 1412 and 1416.

St Mark by Andrea Mantegna, 1448.

Mark the Evangelist with the lion, 1524.

A painted miniature in an Armenian Gospel manuscript from 1609, held by the Bodleian Library.

Saint Mark on a 17th-century naive painting by unknown artist in the choir of St Mary church (Sankta Maria kyrka) in Åhus, Sweden.

St. Mark writes his Evangelium at the dictation of St. Peter, by Pasquale Ottino, 17th century, Beaux-Arts, Bordeaux.

Mark the Evangelist by Il Pordenone (c. 1484 – 1539).

Saint Mark the Evangelist Icon from the royal gates of the central iconostasis of the Kazan Cathedral in Saint Petersburg, 1804.

An icon of Saint Mark the Evangelist, 1657.

Major shrines[]

- Basilica di San Marco (Venice, Italy)

- Saint Mark's Coptic Orthodox Cathedral (Alexandria, Egypt)

- Saint Mark's Church (Serbian Orthodox) in Belgrade, Serbia

- Saint Mark's Coptic Orthodox Cathedral (Cairo, Egypt)

- St. Mark's Church in-the-Bowery, New York City

See also[]

- Baucalis

- Feast of Saint Mark

- Gospel of John

- Gospel of Luke

- Gospel of Mark

- Gospel of Matthew

- John the Evangelist

- Luke the Evangelist

- Matthew the Evangelist

- Saint Mark the Evangelist, patron saint archive

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "St. Mark The Apostle, Evangelist". Coptic Orthodox Church Network. Retrieved November 21, 2012.

- ^ Walsh, p. 21.

- ^ Senior, Donald P. (1998), "Mark", in Ferguson, Everett (ed.), Encyclopedia of Early Christianity (2nd ed.), New York and London: Garland Publishing, Inc., p. 720, ISBN 0-8153-3319-6

- ^ Lane, William L. (1974). "The Author of the Gospel". The Gospel According to Mark. New International Commentary on the New Testament. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. pp. 21–3. ISBN 978-0-8028-2502-5.

- ^ Mark: Images of an Apostolic Interpreter p55 C. Clifton Black – 2001 –"... infrequent occurrence in the Septuagint (Num 36:11; Tob 7:2) to its presence in Josephus (JW 1.662; Ant 1.290, 15.250) and Philo (On the Embassy to Gaius 67), anepsios consistently carries the connotation of "cousin," though ..."

- ^ Hippolytus. "The same Hippolytus on the Seventy Apostles". Ante-Nicene Fathers.

- ^ Finegan, Jack (1998). Handbook of Biblical Chronology. Peabody, MA: Hendrickson. p. 374. ISBN 978-1-56563-143-4.

- ^ "Egypt". Berkley Center for Religion, Peace, and World Affairs. Archived from the original on December 20, 2011. Retrieved December 14, 2011. See drop-down essay on "Islamic Conquest and the Ottoman Empire"

- ^ "The Christian Coptic Orthodox Church Of Egypt". Encyclopedia Coptica. Archived from the original on August 31, 2005. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- ^ Bunson, Matthew; Bunson, Margaret; Bunson, Stephen (1998). Our Sunday Visitor's Encyclopedia of Saints. Huntington, Indiana: Our Sunday Visitor Publishing Division. p. 401. ISBN 0-87973-588-0.

- ^ "Catholic Encyclopedia, St. Mark". Retrieved March 1, 2013.

- ^ "Acts 15:36–40". Bible Gateway.

- ^ "2timothy 4:11 NASB – Only Luke is with me. Pick up Mark and – Bible Gateway". Bible Gateway.

- ^ "Philemon 1:24". Bible Gateway.

- ^ E. P. Sanders (30 November 1995). The Historical Figure of Jesus. Penguin Books Limited. p. 103. ISBN 978-0-14-192822-7.

We do not know who wrote the gospels. They presently have headings: ‘according to Matthew’, ‘according to Mark’, ‘according to Luke’ and ‘according to John’. The Matthew and John who are meant were two of the original disciples of Jesus. Mark was a follower of Paul, and possibly also of Peter; Luke was one of Paul's converts.5 These men – Matthew, Mark, Luke and John – really lived, but we do not know that they wrote gospels. Present evidence indicates that the gospels remained untitled until the second half of the second century.

- ^ Bart D. Ehrman (2000:43) The New Testament: a historical introduction to early Christian writings. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Ehrman, Bart D. (2005). Lost Christianities: The Battles for Scripture and the Faiths We Never Knew. Oxford University Press. p. 235. ISBN 978-0-19-518249-1.

- ^ Nickle, Keith Fullerton (January 1, 2001). The Synoptic Gospels: An Introduction. Westminster John Knox Press. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-664-22349-6.

- ^ Ehrman, Bart D. (November 1, 2004). Truth and Fiction in The Da Vinci Code : A Historian Reveals What We Really Know about Jesus, Mary Magdalene, and Constantine. Oxford University Press, USA. p. 110. ISBN 978-0-19-534616-9.

- ^ Hierapolis, Papias of. "Exposition of the Oracles of the Lord". newadvent.org.

- ^ Harrington, Daniel J. (1990), "The Gospel According to Mark", in Brown, Raymond E.; Fitzmyer, Joseph A.; Murphy, Roland E. (eds.), The New Jerome Biblical Commentary, Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, p. 596, ISBN 0-13-614934-0

- ^ D. A. Carson, Douglas J. Moo and Leon Morris, An Introduction to the New Testament (Apollos, 1992), 93.

- ^ Wansbrough, Henry (22 April 2010). Muddiman, John; Barton, John (eds.). The Gospels. Oxford University Press. p. 243. ISBN 978-0-19-958025-5.

Finally it is important to realize that none of the four gospels originally included an attribution to an author. All were anonymous, and it is only from the fragmentary and enigmatic and—according to Eusebius, from whom we derive the quotation—unreliable evidence of Papias in 120/130 CE that we can begin to piece together any external evidence about the names of their authors and their compilers. This evidence is so difficult to interpret that most modern scholars form their opinions from the content of the gospels themselves, and only then appeal selectively to the external evidence for confirmation of their findings.

- ^ Moessner, David P. (23 June 2004). Snodgrass, Klyne (ed.). "Response to Dunn". Ex Auditu - Volume 16. Wipf and Stock Publishers: 51. ISBN 978-1-4982-3252-4. ISSN 0883-0053.

- ^ University of Navarre (1992), The Navarre Bible: Saint Mark's Gospel (2nd ed.), Dublin: Four Court’s Press, p. 172, ISBN 1-85182-092-2

- ^ University of Navarre (1992), The Navarre Bible: Saint Mark's Gospel (2nd ed.), Dublin: Four Court’s Press, p. 179, ISBN 1-85182-092-2

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Pope Shenouda III, The Beholder of God Mark the Evangelist Saint and Martyr, Chapter One. Tasbeha.org

- ^ "About the Diocese". Coptic Orthodox Diocese of the Southern United States.

- ^ "Saint Mark". Retrieved May 14, 2009.

- ^ Pope Shenouda III. The Beholder of God Mark the Evangelist Saint and Martyr, Chapter Seven. Tasbeha.org

- ^ "The Calendar". The Church of England. Retrieved 2021-03-27.

- ^ Donald M. Nicol, Byzantium and Venice: A Study in diplomatic and cultural relations (Cambridge: University Press, 1988), p. 24

- ^ Carboni, Stefano (2007). Venice and the Islamic World, 828-1797. Yale University Press. p. 14. ISBN 9780300124309. Retrieved 21 September 2020.

- ^ Nicol, Byzantium and Venice, pp. 24–6

- ^ Okey, Thomas (1904), Venice and Its Story, London: J. M. Dent & Co.

- ^ "Section dedicated to the recovery of St. Mark's body". Basilicasanmarco.it. Retrieved February 17, 2010.

- ^ Meinardus, Otto F.A. (March 21, 2006). "About the Laity of the Coptic Church" (PDF). Coptic Church Review. 27 (1): 11–12. Retrieved November 22, 2016.

- ^ Didron, Adolphe Napoléon (February 20, 1886). Christian Iconography: The Trinity. Angels. Devils. Death. The soul. The Christian scheme. Appendices. G. Bell. p. 356 – via Internet Archive.

St. Mark iconography.

- ^ "St. Mark in Art". www.christianiconography.info.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Saint Mark. |

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "St. Mark". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Schem, A. J. (1879). . The American Cyclopædia.

- "St. Mark in the New Testament", "St. Mark in Early Tradition"; two articles by Henry Barclay Swete

- Works by Mark the Evangelist at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- AD 5 births

- 68 deaths

- 1st-century Popes and Patriarchs of Alexandria

- 1st-century Christian martyrs

- 1st-century writers

- Burials at Saint Mark's Coptic Orthodox Cathedral (Alexandria)

- Christian missionaries in Africa

- Early Jewish Christians

- Gospel of Mark

- Saints from Roman Egypt

- People in Acts of the Apostles

- Christian writers

- Seventy disciples

- Four Evangelists

- Body snatching

- Anglican saints