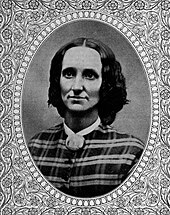

Mary Baker Eddy

Mary Baker Eddy | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Mary Morse Baker July 16, 1821 Bow, New Hampshire, U.S. |

| Died | December 3, 1910 (aged 89) Newton, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Resting place | Mount Auburn Cemetery, Cambridge, Massachusetts |

| Other names | Mary Baker Glover, Mary Patterson, Mary Baker Glover Eddy, Mary Baker G. Eddy |

| Known for | Founder of Christian Science |

Notable work | Science and Health (1875) |

| Spouse(s) |

|

| Children | George Washington Glover II (1844–1915) |

| Parent(s) | Mark Baker (1785–1865) Abigail Ambrose Baker (1784–1849) |

Mary Baker Eddy (July 16, 1821 – December 3, 1910) was an American religious leader and author who founded The Church of Christ, Scientist, in New England in 1879.[1][2] She also founded The Christian Science Monitor, a Pulitzer Prize-winning[3] secular newspaper, in 1908 and three religious magazines: the Christian Science Sentinel, The Christian Science Journal, and The Herald of Christian Science. She wrote numerous books and articles, the most notable of which was Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures, which had sold over nine million copies as of 2001.[4]

Members of The First Church of Christ, Scientist consider Eddy the "discoverer" of Christian Science, and adherents are therefore known as Christian Scientists or students of Christian Science.[5] The church is sometimes informally known as the Christian Science church.

Eddy was named one of the "100 Most Significant Americans of All Time" in 2014 by Smithsonian Magazine,[6] and her book Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures was ranked as one of the "75 Books by Women Whose Words Have Changed the World" by the Women's National Book Association.[7]

Early life[]

Bow, New Hampshire[]

Family[]

Eddy was born Mary Morse Baker in a farmhouse in Bow, New Hampshire, to farmer Mark Baker (d. 1865) and his wife Abigail Barnard Baker, née Ambrose (d. 1849). Eddy was the youngest of the Bakers' six children: boys Samuel Dow (1808), Albert (1810), and George Sullivan (1812), followed by girls Abigail Barnard (1816), Martha Smith (1819), and Mary Morse (1821).[8]

Mark Baker was a strongly religious man from a Protestant Congregationalist background, a firm believer in the final judgment and eternal damnation, according to Eddy.[9] McClure's magazine published a series of articles in 1907 that were highly critical of Eddy, stating that Baker's home library had consisted of the Bible.[10] Eddy responded that this was untrue and that her father had been an avid reader.[11][12] According to Eddy, her father had been a justice of the peace at one point and a chaplain of the New Hampshire State Militia.[13] He developed a reputation locally for being disputatious; one neighbor described him as "[a] tiger for a temper and always in a row."[14] McClure's described him as a supporter of slavery and alleged that he had been pleased to hear about Abraham Lincoln's death.[15] Eddy responded that Baker had been a "strong believer in States' rights, but slavery he regarded as a great sin."[13]

The Baker children inherited their father's temper, according to McClure's; they also inherited his good looks, and Eddy became known as the village beauty. Life was nevertheless spartan and repetitive. Every day began with lengthy prayer and continued with hard work. The only rest day was the Sabbath.[16]

Health[]

Eddy and her father reportedly had a volatile relationship. Ernest Sutherland Bates and John V. Dittemore wrote in 1932, relying on the Cather and Milmine history of Eddy (but see below), that Baker sought to break Eddy's will with harsh punishment, although her mother often intervened; in contrast to Mark Baker, Eddy's mother was described as devout, quiet, light-hearted, and kind.[17] Eddy experienced periods of sudden illness, perhaps in an effort to control her father's attitude toward her.[18] Those who knew the family described her as suddenly falling to the floor, writhing and screaming, or silent and apparently unconscious, sometimes for hours.[19][20] Robert Peel, one of Eddy's biographers, worked for the Christian Science church and wrote in 1966:

This was when life took on the look of a nightmare, overburdened nerves gave way, and she would end in a state of unconsciousness that would sometimes last for hours and send the family into a panic. On such an occasion Lyman Durgin, the Baker's teen-age chore boy, who adored Mary, would be packed off on a horse for the village doctor ...[21]

Gillian Gill wrote in 1998 that Eddy was often sick as a child and appears to have suffered from an eating disorder, but reports may have been exaggerated concerning hysterical fits.[22] Eddy described her problems with food in the first edition of Science and Health (1875). She wrote that she had suffered from chronic indigestion as a child and, hoping to cure it, had embarked on a diet of nothing but water, bread, and vegetables, at one point consumed just once a day: "Thus we passed most of our early years, as many can attest, in hunger, pain, weakness, and starvation."[23]

Eddy experienced near invalidism as a child and most of her life until her discovery of Christian Science. Like most life experiences, it formed her lifelong, diligent research for a remedy from almost constant suffering. Eddy writes in her autobiography, "From my very childhood I was impelled by a hunger and thirst after divine things, - a desire for something higher and better than matter, and apart from it, - to seek diligently for the knowledge of God as the one great and ever-present relief from human woe." She also writes on page 33 of the chapter, "Medical Experiments", in her autobiography, "I wandered through the dim mazes of 'materia medica,' till I was weary of 'scientific guessing,' as it has been well called. I sought knowledge from the different schools, - allopathy, homeopathy, hydropathy, electricity, and from various humbugs, - but without receiving satisfaction."[24]

Tilton, New Hampshire[]

In 1836 when Eddy was about 14-15, she moved with her family to the town of Sanbornton Bridge, New Hampshire, approximately twenty miles (32 km) north of Bow. Sanbornton Bridge would subsequently be renamed in 1869 as Tilton.[25]

My father was taught to believe that my brain was too large for my body and so kept me much out of school, but I gained book-knowledge with far less labor than is usually requisite. At ten years of age I was as familiar with Lindley Murray's Grammar as with the Westminster Catechism; and the latter I had to repeat every Sunday. My favorite studies were natural philosophy, logic, and moral science. From my brother Albert, I received lessons in the ancient tongues, Hebrew, Greek, and Latin.[26]

Ernest Bates and John Dittemore write that Eddy was not able to attend Sanbornton Academy when the family first moved there but was required instead to start at the district school (in the same building) with the youngest girls. She withdrew after a month because of poor health, then received private tuition from the Reverend Enoch Corser. She entered Sanbornton Academy in 1842.[27]

She was received into the Congregational church in Tilton on 26 July 1838 when she was 17, according to church records published by McClure's in 1907. Eddy had written in her autobiography in 1891 that she was 12 when this happened, and that she had discussed the idea of predestination with the pastor during the examination for her membership; this may have been an attempt to reflect the story of a 12-year-old Jesus in the Temple.[28][29] She wrote in response to the McClure's article that the date of her church membership may have been mistaken by her.[30] Eddy objected so strongly to the idea of predestination and eternal damnation that it made her ill:

My mother, as she bathed my burning temples, bade me lean on God's love, which would give me rest if I went to Him in prayer, as I was wont to do, seeking His guidance. I prayed; and a soft glow of ineffable joy came over me. The fever was gone and I rose and dressed myself in a normal condition of health. Mother saw this and was glad. The physician marveled; and the "horrible decree" of Predestination – as John Calvin rightly called his own tenet – forever lost its power over me.[31]

Marriage, widowhood[]

Eddy was badly affected by four deaths in the 1840s.[32] She regarded her brother Albert as a teacher and mentor, but he died in 1841. In 1844, her first husband George Washington Glover (a friend of her brother Samuel) died after six months of marriage. They had married in December 1843 and set up home in Charleston, South Carolina, where Glover had business, but he died of yellow fever in June 1844 while living in Wilmington, North Carolina. Eddy was with him in Wilmington, six months pregnant. She had to make her way back to New Hampshire, 1,400 miles (2,300 km) by train and steamboat, where her only child George Washington II was born on 12 September in her father's home.[33][34]

Her husband's death, the journey back, and the birth left her physically and mentally exhausted, and she ended up bedridden for months.[35] She tried to earn a living by writing articles for the New Hampshire Patriot and various Odd Fellows and Masonic publications. She also worked as a substitute teacher in the New Hampshire Conference Seminary, and ran her own kindergarten for a few months in 1846, apparently refusing to use corporal punishment.[36]

Then her mother died in November 1849. Eddy wrote to one of her brothers: "What is left of earth to me!" Her mother's death was followed three weeks later by the death of her fiancé, lawyer John Bartlett.[37] In 1850, Eddy wrote, her son was sent away to be looked after by the family's nurse; he was four years old by then.[38] Sources differ as to whether Eddy could have prevented this.[39] It was difficult for a woman in her circumstances to earn money and, according to the legal doctrine of coverture, women in the United States during this period could not be their own children's guardians. When their husbands died, they were left in a legally vulnerable position.[40]

Mark Baker remarried in 1850; his second wife Elizabeth Patterson Duncan (d. 6 June 1875) had been widowed twice, and had some property and income from her second marriage.[41] Baker apparently made clear to Eddy that her son would not be welcome in the new marital home.[39] She wrote:

A few months before my father's second marriage ... my little son, about four years of age, was sent away from me, and put under the care of our family nurse, who had married, and resided in the northern part of New Hampshire. I had no training for self-support, and my home I regarded as very precious. The night before my child was taken from me, I knelt by his side throughout the dark hours, hoping for a vision of relief from this trial.[42]

George was sent to stay with various relatives, and Eddy decided to live with her sister Abigail. Abigail apparently also declined to take George, then six years old.[41] Eddy married again in 1853. Her second husband, Daniel Patterson, was a dentist and apparently said that he would become George's legal guardian; but he appears not to have gone ahead with this, and Eddy lost contact with her son when the family that looked after him, the Cheneys, moved to Minnesota, and then her son several years later enlisted in the Union army during the Civil War. She did not see him again until he was in his thirties:

My dominant thought in marrying again was to get back my child, but after our marriage his stepfather was not willing he should have a home with me. A plot was consummated for keeping us apart. The family to whose care he was committed very soon removed to what was then regarded as the Far West. After his removal a letter was read to my little son, informing him that his mother was dead and buried. Without my knowledge a guardian was appointed him, and I was then informed that my son was lost. Every means within my power was employed to find him, but without success. We never met again until he had reached the age of thirty-four, had a wife and two children, and by a strange providence had learned that his mother still lived, and came to see me in Massachusetts.[42]

Study with Phineas Quimby[]

Mesmerism had become popular in New England; and on October 14, 1861, Eddy's husband at the time, Dr. Patterson, wrote to mesmerist Phineas Parkhurst Quimby, who reportedly cured people without medicine, asking if he could cure his wife.[43] Quimby replied that he had too much work in Portland, Maine, and that he could not visit her, but if Patterson brought his wife to him he would treat her.[44] Eddy did not immediately go, instead trying the water cure at Dr. Vail's Hydropathic Institute, but her health deteriorated even further.[45][46] A year later, in October 1862, Eddy first visited Quimby.[47][48] She improved considerably, and publicly declared that she had been able to walk up 182 steps to the dome of city hall after a week of treatment.[49] The cures were temporary, however, and Eddy suffered relapses.[50]

Despite the temporary nature of the "cure", she attached religious significance to it, which Quimby did not.[51] She believed that it was the same type of healing that Christ had performed.[52] From 1862 to 1865, Quimby and Eddy engaged in lengthy discussions about healing methods practiced by Quimby and others.[53][54][55] She took notes on her own ideas on healing, as well as writing dictations from him and "correcting" them with her own ideas, some of which possibly ended up in the "Quimby manuscripts" that were published later and attributed to him.[56][57] Despite Quimby not being especially religious, he embraced the religious connotations Eddy was bringing to his work, since he knew his more religious patients would appreciate it.[58]

Phineas Quimby died on January 16, 1866, shortly after Eddy's father.[a] Later, Quimby became the "single most controversial issue" of Eddy's life according to biographer Gillian Gill, who stated: "Rivals and enemies of Christian Science found in the dead and long forgotten Quimby their most important weapon against the new and increasingly influential religious movement", as Eddy was "accused of stealing Quimby's philosophy of healing, failing to acknowledge him as the spiritual father of Christian Science, and plagiarizing his unpublished work."[60] However, Gill continued:

"I am now firmly convinced, having weighed all the evidence I could find in published and archival sources, that Mrs. Eddy’s most famous biographer-critics—Peabody, Milmine, Dakin, Bates and Dittemore, and Gardner—have flouted the evidence and shown willful bias in accusing Mrs. Eddy of owing her theory of healing to Quimby and of plagiarizing his unpublished work."[61]

Quimby wrote extensive notes from the 1850s until his death in 1866. Some of his manuscripts, in his own hand, appear in a collection of his writings in the Library of Congress, but far more common was that the original Quimby drafts were edited and rewritten by his copyists. The transcriptions were heavily edited by those copyists to make them more readable.[62] Rumors of Quimby "manuscripts" began to circulate in the 1880s when Julius Dresser began accusing Eddy of stealing from Quimby.[63] Quimby's son, George, who disliked Eddy, did not want any of the manuscripts published, and kept what he owned away from the Dressers until after his death.[64] In 1921, Julius's son, Horatio Dresser, published various copies of writings that he entitled The Quimby Manuscripts to support these claims, but left out papers that didn't serve his view.[65] Further complicating the matter is that, as stated above, no originals of most of the copies exist; and according to Gill, Quimby's personal letters, which are among the items in his own handwriting, "eloquently testify to his incapacity to spell simple words or write a simple, declarative sentence. Thus there is no documentary proof that Quimby ever committed to paper the vast majority of the texts ascribed to him, no proof that he produced any text that someone else could, even in the loosest sense, 'copy.'"[66] In addition, it has been averred that the dates given to the papers seem to be guesses made years later by Quimby's son, and although critics have claimed Quimby used terms like "science of health" in 1859 before he met Eddy, the alleged lack of proper dating in the papers makes this impossible to prove.[67][68]

According to J. Gordon Melton: "Certainly Eddy shared some ideas with Quimby. She differed with him in some key areas, however, such as specific healing techniques. Moreover, she did not share Quimby's hostility toward the Bible and Christianity."[69]

Fall in Swampscott[]

On February 1, 1866, Eddy slipped and fell on ice while walking in Swampscott, Massachusetts, causing a spinal injury:

On the third day thereafter, I called for my Bible, and opened it at Matthew, 9:2 [And, behold, they brought to him a man sick of the palsy, lying on a bed: and Jesus seeing their faith said unto the sick of the palsy; Son, be of good cheer; thy sins be forgiven thee.(King James Bible) ]. As I read, the healing Truth dawned upon my sense; and the result was that I arose, dressed myself, and ever after was in better health than I had before enjoyed. That short experience included a glimpse of the great fact that I have since tried to make plain to others, namely, Life in and of Spirit; this Life being the sole reality of existence.[70]

Two contemporaneous news accounts are recorded of this event:

Lynn Reporter, February 3, 1866:

"Mrs. Mary M. Patterson, of Swampscott, fell upon the ice near the corner of Market and Oxford streets, on Thursday evening, and was severely injured. She was taken up in an insensible condition and carried to the residence of S. M. Bubier, Esq., near by, where she was kindly cared for during the night. Dr. Cushing, who was called, found her injuries to be internal, and of a very serious nature, inducing spasms and intense suffering. She was removed to her home in Swampscott yesterday afternoon, though in a very critical condition."

Salem Register, February 5, 1866:

"Mrs. Mary M. Patterson of Swampscott was severely injured by a fall upon the ice near the corner of Market and Oxford streets, Lynn, on Thursday. It is feared she will not recover."

These contemporaneous news articles both reported on the seriousness of Eddy’s condition. Compare the statement in the Register, “It is feared she will not recover” and the statement in the Reporter that Eddy’s injuries were “internal” and she was removed to her home “in a very critical condition,” to Cushing’s affidavit 38 years later, in 1904: “I did not at any time declare, or believe, that there was no hope of Mrs. Patterson’s recovery, or that she was in a critical condition.” Cushing's effort to downplay the seriousness of the accident perhaps reached its most extreme point in this letter from Gordon Clark, confirmed Eddy critic and author of The Church of St. Bunco, to the editor of the Boston Herald, March 2, 1902:

"I have a recent letter from him [i.e., Dr. A. M. Cushing] in which he utterly denies the whole substance of her assertions. Her injury was mostly a jar of her imagination and a contusion, on her veracity."

Eddy later filed a claim for money from the city of Lynn for her injury on the grounds that she was "still suffering from the effects of that fall" (though she afterwards withdrew the lawsuit).[71] Gill writes that Eddy's claim was probably made under financial pressure from her husband at the time. Her neighbors believed her sudden recovery to be a near-miracle.[72]

Eddy wrote in her autobiography, Retrospection and Introspection, that she devoted the next three years of her life to biblical study and what she considered the discovery of Christian Science: "I then withdrew from society about three years,--to ponder my mission, to search the Scriptures, to find the Science of Mind that should take the things of God and show them to the creature, and reveal the great curative Principle, --Deity."[73]

Eddy became convinced that illness could be healed through an awakened thought brought about by a clearer perception of God and the explicit rejection of drugs, hygiene, and medicine, based on the observation that Jesus did not use these methods for healing:

It is plain that God does not employ drugs or hygiene, nor provide them for human use; else Jesus would have recommended and employed them in his healing. ... The tender word and Christian encouragement of an invalid, pitiful patience with his fears and the removal of them, are better than hecatombs of gushing theories, stereotyped borrowed speeches, and the doling of arguments, which are but so many parodies on legitimate Christian Science, aflame with divine Love.[74]

Spiritualism[]

Eddy separated from her second husband Daniel Patterson, after which she boarded for four years with several families in Lynn, Amesbury, and elsewhere. Frank Podmore wrote:

But she was never able to stay long in one family. She quarrelled successively with all her hostesses, and her departure from the house was heralded on two or three occasions by a violent scene. Her friends during these years were generally Spiritualists; she seems to have professed herself a Spiritualist, and to have taken part in séances. She was occasionally entranced, and had received "spirit communications" from her deceased brother Albert. Her first advertisement as a healer appeared in 1868, in the Spiritualist paper, The Banner of Light. During these years she carried about with her a copy of one of Quimby's manuscripts giving an abstract of his philosophy. This manuscript she permitted some of her pupils to copy.[75]

After she became well known, reports surfaced that Eddy was a medium in Boston at one time.[76] At the time when she was said to be a medium there, she lived some distance away.[77] According to Gill, Eddy knew spiritualists and took part in some of their activities, but was never a convinced believer.[78] For example, she visited her friend Sarah Crosby in 1864, who believed in Spiritualism. According to Sibyl Wilbur, Eddy attempted to show Crosby the folly of it by pretending to channel Eddy's dead brother Albert and writing letters which she attributed to him.[79] In regard to the deception, biographer Hugh Evelyn Wortham commented that "Mrs. Eddy's followers explain it all as a pleasantry on her part to cure Mrs. Crosby of her credulous belief in spiritualism."[80] However, Martin Gardner has argued against this, stating that Eddy was working as a spiritualist medium and was convinced by the messages. According to Gardner, Eddy's mediumship converted Crosby to Spiritualism.[81]

In one of her spiritualist trances to Crosby, Eddy gave a message that was supportive of Phineas Parkhurst Quimby, stating "P. Quimby of Portland has the spiritual truth of diseases. You must imbibe it to be healed. Go to him again and lean on no material or spiritual medium."[82][83] The paragraph that included this quote was later omitted from an official sanctioned biography of Eddy.[83]

Between 1866 and 1870, Eddy boarded at the home of Brene Paine Clark who was interested in Spiritualism.[84] Seances were often conducted there, but Eddy and Clark engaged in vigorous, good-natured arguments about them.[85] Eddy's arguments against Spiritualism convinced at least one other who was there at the time—Hiram Crafts—that "her science was far superior to spirit teachings."[86] Clark's son George tried to convince Eddy to take up Spiritualism, but he said that she abhorred the idea.[87] According to Cather and Milmine, Mrs. Richard Hazeltine attended seances at Clark's home,[88] and she said that Eddy had acted as a trance medium, claiming to channel the spirits of the Apostles.[89]

Mary Gould, a Spiritualist from Lynn, claimed that one of the spirits that Eddy channeled was Abraham Lincoln. According to eyewitness reports cited by Cather and Milmine, Eddy was still attending séances as late as 1872.[90] In these later séances, Eddy would attempt to convert her audience into accepting Christian Science.[91] Eddy showed extensive familiarity with Spiritualist practice but denounced it in her Christian Science writings.[92] Historian Ann Braude wrote that there were similarities between Spiritualism and Christian Science, but the main difference was that Eddy came to believe, after she founded Christian Science, that spirit manifestations had never really had bodies to begin with, because matter is unreal and that all that really exists is spirit, before and after death.[93]

Divorce, publishing her work[]

Eddy divorced Daniel Patterson for adultery in 1873. She published her work in 1875 in a book entitled Science and Health (years later retitled Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures) which she called the textbook of Christian Science, after several years of offering her healing method. The first publication run was 1,000 copies, which she self-published. During these years, she taught what she considered the science of "primitive Christianity" to at least 800 people.[94] Many of her students became healers themselves. The last 100 pages of Science and Health (chapter entitled "Fruitage") contains testimonies of people who claimed to have been healed by reading her book. She made numerous revisions to her book from the time of its first publication until shortly before her death.[95]

Marriage to Asa Gilbert Eddy[]

On 1 January 1877, she married Asa Gilbert Eddy, becoming Mary Baker Eddy in a small ceremony presided over by a Unitarian minister.[96] In 1881, the Mary Baker Eddy started the Massachusetts Metaphysical College with a charter from the state which allowed her to grant degrees.[97] In 1882, the Eddys moved to Boston, and Gilbert Eddy died that year.[98]

Alleged influence of Hinduism[]

In the 24th edition of Science and Health, up to the 33rd edition, Eddy admitted the harmony between Vedanta philosophy and Christian Science. She also quoted certain passages from an English translation of the Bhagavad Gita, but they were later removed. According to Gill, in the 1891 revision Eddy removed from her book all the references to Eastern religions which her editor, Reverend James Henry Wiggin, had introduced.[99] On this issue Swami Abhedananda wrote:

Mrs. Eddy quoted certain passages from the English edition of the Bhagavad-Gita, but unfortunately, for some reason, those passages of the Gita were omitted in the 34th edition of the book, Science and Health ... if we closely study Mrs. Eddy's book, we find that Mrs. Eddy has incorporated in her book most of the salient features of Vedanta philosophy, but she denied the debt flatly.[100]

Other writers, such as Jyotirmayananda Saraswati, have said that Eddy may have been influenced by ancient Hindu philosophy.[101] The historian Damodar Singhal wrote:

The Christian Science movement in America was possibly influenced by India. The founder of this movement, Mary Baker Eddy, in common with the Vedantins, believed that matter and suffering were unreal, and that a full realization of this fact was essential for relief from ills and pains ... The Christian Science doctrine has naturally been given a Christian framework, but the echoes of Vedanta in its literature are often striking.[102]

Wendell Thomas in Hinduism Invades America (1930) suggested that Eddy may have discovered Hinduism through the teachings of the New England Transcendentalists such as Bronson Alcott.[103] Stephen Gottschalk, in his The Emergence of Christian Science in American Religious Life (1973), wrote:

The association of Christian Science with Eastern religion would seem to have had some basis in Mrs Eddy's own writings. For in some early editions of Science and Health she had quoted from and commented favorably upon a few Hindu and Buddhist texts ... None of these references, however, was to remain a part of Science and Health as it finally stood ... Increasingly from the mid-1880s on, Mrs Eddy made a sharp distinction between Christian Science and Eastern religions.[104]

In regards to the influence of Eastern religions on her discovery of Christian Science, Eddy states in The First Church of Christ, Scientist and Miscellany: "Think not that Christian Science tends towards Buddhism or any other 'ism'. Per contra, Christian Science destroys such tendency."[105]

Building a church[]

Eddy devoted the rest of her life to the establishment of the church, writing its bylaws, The Manual of The Mother Church, and revising Science and Health. By the 1870s she was telling her students, "Some day I will have a church of my own."[106] In 1879 she and her students established the Church of Christ, Scientist, "to commemorate the word and works of our Master [Jesus], which should reinstate primitive Christianity and its lost element of healing."[107] In 1892 at Eddy's direction, the church reorganized as The First Church of Christ, Scientist, "designed to be built on the Rock, Christ. ... "[108] In 1881, she founded the Massachusetts Metaphysical College,[109] where she taught approximately 800 students between the years 1882 and 1889, when she closed it.[110] Eddy charged her students $300 each for tuition, a large sum for the time.[111]

Her students spread across the country practicing healing, and instructing others. Eddy authorized these students to list themselves as Christian Science Practitioners in the church's periodical, The Christian Science Journal. She also founded the Christian Science Sentinel, a weekly magazine with articles about how to heal and testimonies of healing.

In 1888, a reading room selling Bibles, her writings and other publications opened in Boston.[112] This model would soon be replicated, and branch churches worldwide maintain more than 1,200 Christian Science Reading Rooms today.[113]

In 1894 an edifice for The First Church of Christ, Scientist was completed in Boston (The Mother Church). In the early years Eddy served as pastor. In 1895 she ordained the Bible and Science and Health as the pastor.[114]

Eddy founded The Christian Science Publishing Society in 1898, which became the publishing home for numerous publications launched by her and her followers.[115] In 1908, at the age of 87, she founded The Christian Science Monitor, a daily newspaper.[116] She also founded the Christian Science Journal in 1883,[117] a monthly magazine aimed at the church's members and, in 1898,[118] the Christian Science Sentinel, a weekly religious periodical written for a more general audience, and the Herald of Christian Science, a religious magazine with editions in many languages.[119]

Malicious animal magnetism[]

The opposite of Christian Science mental healing was the use of mental powers for destructive or selfish reasons – for which Eddy used terms such as animal magnetism, hypnotism, or mesmerism interchangeably.[120][121] "Malicious animal magnetism", sometimes abbreviated as M.A.M., is what Catherine Albanese called "a Calvinist devil lurking beneath the metaphysical surface".[122] As there is no personal devil or evil in Christian Science, M.A.M. or mesmerism became the explanation for the problem of evil.[123][124] Eddy was concerned that a new practitioner could inadvertently harm a patient through unenlightened use of their mental powers, and that less scrupulous individuals could use as a weapon.[125]

Animal magnetism became one of the most controversial aspects of Eddy's life. The critical McClure's biography spends a significant amount of time on malicious animal magnetism, which it uses to make the case that Eddy had paranoia.[124] During the Next Friends suit, it was used to charge Eddy with incompetence and "general insanity".[126]

According to Gillian Gill, Eddy's experience with Richard Kennedy, one of her early students, was what led her to began her examination of malicious animal magnetism.[127] Eddy had agreed to form a partnership with Kennedy in 1870, in which she would teach him how to heal, and he would take patients.[128] The partnership was rather successful at first, but by 1872 Kennedy had fallen out with his teacher and torn up their contract.[129] Although there were multiple issues raised, the main reason for the break according to Gill was Eddy's insistence that Kennedy stop "rubbing" his patient's head and solar plexus, which she saw as harmful since, as Gill states, "traditionally in mesmerism or hypnosis the head and abdomen were manipulated so that the subject would be prepared to enter into trance."[130] Kennedy clearly did believe in clairvoyance, mind reading, and absent mesmeric treatment; and after their split Eddy believed that Kennedy was using his mesmeric abilities to try to harm her and her movement.[127]

In 1882 Eddy publicly claimed that her last husband, Asa Gilbert Eddy, had died of "mental assassination".[131] Daniel Spofford was another Christian Scientist expelled by Eddy after she accused him of practicing malicious animal magnetism.[132] This gained notoriety in a case irreverently dubbed the "Second Salem Witch Trial".[133] Critics of Christian Science blamed fear of animal magnetism if a Christian Scientist committed suicide, which happened with Mary Tomlinson, the sister of Irving C. Tomlinson.[134]

Later, Eddy set up "watches" for her staff to pray about challenges facing the Christian Science movement and to handle animal magnetism which arose.[135] Gill writes that Eddy got the term from the New Testament account of the garden of Gethsemane, where Jesus chastises his disciples for being unable to "watch" even for a short time; and that Eddy used it to refer to "a particularly vigilant and active form of prayer, a set period of time when specific people would put their thoughts toward God, review questions and problems of the day, and seek spiritual understanding."[135] Critics such as Georgine Milmine in Mclure's, Edwin Dakin, and John Dittemore, all claimed this was evidence that Eddy had a great fear of malicious animal magnetism; although Gilbert Carpenter, one of Eddy's staff at the time, insisted she was not fearful of it, and that she was simply being vigilant.[135] According to Eddy it was important to challenge animal magnetism, because, as Gottschalk says, its "apparent operation claims to have a temporary hold on people only through unchallenged mesmeric suggestion. As this is exposed and rejected, she maintained, the reality of God becomes so vivid that the magnetic pull of evil is broken, its grip on one’s mentality is broken, and one is freer to understand that there can be no actual mind or power apart from God."[136]

As time went on Eddy tried to lessen the focus on animal magnetism within the movement, and worked to clearly define it as unreality which only had power if one conceded power and reality to it.[137] Eddy wrote in Science and Health: "Animal magnetism has no scientific foundation, for God governs all that is real, harmonious, and eternal, and His power is neither animal nor human. Its basis being a belief and this belief animal, in Science animal magnetism, mesmerism, or hypnotism is a mere negation, possessing neither intelligence, power, nor reality, and in sense it is an unreal concept of the so-called mortal mind."[138]

The belief in malicious animal magnetism "remains a part of the doctrine of Christian Science."[139] Christian Scientists use it as a specific term for a hypnotic belief in a power apart from God.[140] They contend that it is "neither mysterious nor complex" and compare it to Paul's discussion of "the carnal mind...enmity against God" in the Bible.[141]

Use of medicine[]

There is controversy about how much Eddy used morphine. Biographers Ernest Sutherland Bates and Edwin Franden Dakin described Eddy as a morphine addict.[142] Miranda Rice, a friend and close student of Eddy, told a newspaper in 1906: "I know that Mrs. Eddy was addicted to morphine in the seventies."[143] A diary kept by Calvin Frye, Eddy's personal secretary, suggests that Eddy occasionally reverted to "the old morphine habit" when she was in pain.[144] Gill writes that the prescription of morphine was normal medical practice at the time, and that "I remain convinced that Mary Baker Eddy was never addicted to morphine."[145]

Eddy recommended to her son that, rather than go against the law of the state, he should have her grandchildren vaccinated. She also paid for a mastectomy for her sister-in-law.[146] Eddy was quoted in the New York Herald on 1 May 1901: "Where vaccination is compulsory, let your children be vaccinated, and see that your mind is in such a state that by your prayers vaccination will do the children no harm. So long as Christian Scientists obey the laws, I do not suppose their mental reservations will be thought to matter much."[147]

Eddy used glasses for several years for very fine print, but later dispensed with them almost entirely.[148] She found she could read fine print with ease.[149] In 1907 Arthur Brisbane interviewed Eddy. At one point he picked up a periodical, selected at random a paragraph, and asked Eddy to read it. According to Brisbane, at the age of eighty six, she read the ordinary magazine type without glasses.[150] Towards the end of her life she was frequently attended by physicians.[151]

Next Friends lawsuit[]

In 1907, the New York World sponsored a lawsuit, known as "", which journalist Erwin Canham described as "designed to wrest from [Eddy] and her trusted officials all control of her church and its activities."[152] During the course of the legal case, four psychiatrists interviewed Eddy, then 86 years old, to determine whether she could manage her own affairs, and concluded that she was able to.[153] Physician Allan McLane Hamilton told The New York Times that the attacks on Eddy were the result of "a spirit of religious persecution that has at last quite overreached itself", and that "there seems to be a manifest injustice in taxing so excellent and capable an old lady as Mrs. Eddy with any form of insanity."[154]

A 1907 article in the Journal of the American Medical Association noted that Eddy exhibited hysterical and psychotic behavior.[155] Psychiatrist Karl Menninger in his book The Human Mind (1927) cited Eddy's paranoid delusions about malicious animal magnetism as an example of a "schizoid personality".[156]

Psychologists Leon Joseph Saul and Silas L. Warner, in their book The Psychotic Personality (1982), came to the conclusion that Eddy had diagnostic characteristics of Psychotic Personality Disorder (PPD).[157] In 1983, psychologists Theodore Barber and Sheryl C. Wilson suggested that Eddy displayed traits of a fantasy prone personality.[158]

Psychiatrist George Eman Vaillant wrote that Eddy was hypochrondriacal.[159] Psychopharmacologist Ronald K. Siegel has written that Eddy's lifelong secret morphine habit contributed to her development of "progressive paranoia".[160]

Death[]

Eddy died on the evening of December 3, 1910, at her home at 400 Beacon Street, in the Chestnut Hill section of Newton, Massachusetts. Her death was announced the next morning, when a city medical examiner was called in.[161] She was buried on December 8, 1910, at Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Her memorial was designed by New York architect Egerton Swartwout (1870–1943). Hundreds of tributes appeared in newspapers around the world, including The Boston Globe, which wrote, "She did a wonderful—an extraordinary work in the world and there is no doubt that she was a powerful influence for good."[162]

Legacy[]

The influence of Eddy's writings has reached outside the Christian Science movement. Richard Nenneman wrote "the fact that Christian Science healing, or at least the claim to it, is a well-known phenomenon, was one major reason for other churches originally giving Jesus' command more attention. There are also some instances of Protestant ministers using the Christian Science textbook [Science and Health], or even the weekly Bible lessons, as the basis for some of their sermons."[71]

The Christian Science Monitor, which was founded by Eddy as a response to the yellow journalism of the day, has gone on to win seven Pulitzer Prizes and numerous other awards.[163]

Residences[]

In 1921, on the 100th anniversary of Eddy's birth, a 100-ton (in rough) and 60–70 tons (hewn) pyramid with a 121 square foot (11.2 m2) footprint was dedicated on the site of her birthplace in Bow, New Hampshire.[164] A gift from James F. Lord, it was dynamited in 1962 by order of the church's Board of Directors. Also demolished was Eddy's former home in Pleasant View, as the Board feared that it was becoming a place of pilgrimage.[165] Eddy is featured on a New Hampshire historical marker (number 105) along New Hampshire Route 9 in Concord.[166]

Several of Eddy's homes are owned and maintained as historic sites by the Longyear Museum and may be visited (the list below is arranged by date of her occupancy):[167]

- 1855–1860 – Hall's Brook Road, North Groton, New Hampshire

- 1860–1862 – Stinson Lake Road, Rumney, New Hampshire

- 1865–1866 – 23 Paradise Road, Swampscott, Massachusetts[168]

- 1868,1870 – 277 Main Street, Amesbury, Massachusetts

- 1868–1870 – 133 Central Street, Stoughton, Massachusetts

- 1875–1882 – Mary Baker Eddy House (NRHP-listed in 2021), 8 Broad Street, Lynn, Massachusetts

- 1889–1892 – 62 North State Street, Concord, New Hampshire

- 1908–1910 – Dupee Estate–Mary Baker Eddy Home (NRHP-listed in 1986), 400 Beacon Street, Chestnut Hill, Newton, Massachusetts.

23 Paradise Road, Swampscott, Massachusetts

277 Main Street, Amesbury, Massachusetts

133 Central Street, Stoughton, Massachusetts

8 Broad Street, Lynn, Massachusetts

400 Beacon Street, Chestnut Hill, Newton, Massachusetts

Selected works[]

- Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures 1910

- Miscellaneous Writings 1883-1896

- Retrospection and Introspection - 1891

- Unity of Good – 1887

- Miscellaneous Writings

- Pulpit and Press

- Rudimental Divine Science

- No and Yes

- Christian Science versus Pantheism

- Message to The Mother Church, 1900

- Message to The Mother Church, 1901

- Message to The Mother Church, 1902

- Christian Healing

- The People's Idea of God, Its Effect on Health and Christianity, 1914

- The First Church of Christ, Scientist, and Miscellany

- The Manual of The Mother Church

- Poems, 1910

- Source: WorldCat[169]

See also[]

- Dupee Estate-Mary Baker Eddy Home in the Chestnut Hill village of Newton, Massachusetts

- Massachusetts Metaphysical College with a complete list of students of Eddy

- Septimus J. Hanna, student of Eddy and vice-president of the Massachusetts Metaphysical College

- William R. Rathvon, student of Eddy, early Christian Scientist and lone person to leave an audio recording of his hearing Lincoln's Gettysburg Address at the age of nine.

- Bliss Knapp, a child when the church was in its formative years. Later, he was a teacher and also lectured for 21 years. His father was one of the first Directors of The Mother Church. Knapp's Book, The Destiny of the Mother Church, which was rejected by the Church but privately published, was quite controversial, and Knapp's opinions of Eddy remain controversial to this day in the Christian Science Church.

- Augusta Emma Stetson, pastor and later First Reader of First Church of Christ, Scientist (New York, New York), excommunicated by the Mother Church in 1909.

- Christian Science Herald

- Christian Science Journal

- Christian Science Monitor

- Christian Science Pleasant View Home

- Christian Science practitioner

- Christian Science Sentinel

- Christian Science Reading Room

Notes[]

References[]

- ^ Stark, 1998, p. 189.

- ^ Mary Baker Eddy. Manual of the Mother Church. 89th ed., Boston: The First Church of Christ, Scientist, 1908 [1895], pp. 17–18.

- ^ "Pulitzer Prizes". Christian Science Monitor. December 21, 2018.

- ^ Paul C. Gutjahr. "Sacred Texts in the United States", Book History, 4, 2001 (335–370), 348. JSTOR 30227336

- ^ Abbott, Deborah. "The Christian Science Tradition" (PDF). Park Ridge Center for the Study of Health, Faith, and Ethics. Retrieved March 8, 2020.

- ^ "100 Most Significant Americans of All Time". Smithsonian.

- ^ "75 Books by Women Whose Words Have Changed the World" (PDF).

- ^ Bates and Dittemore, 1932, p. 3.

- ^ Mary Baker Eddy, Retrospection and Introspection, Christian Science Publishing Society, 1891, 13.

- ^ Cather and Milmine, McClure's, January 1907, p. 232.

- ^ Mary Baker Eddy, "Reply to McClure's Magazine" Archived April 2, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, Christian Science Endtime Center, undated.

- ^ Mary Baker Eddy, The First Church of Christ, Scientist, and Miscellany, Christian Science Publishing Society, 1913, 308.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Eddy, The First Church of Christ, Scientist, and Miscellany, 309.

- ^ Bates and Dittemore 1932, 4–5.

- ^ Cather and Milmine, p. 229.

- ^ Cather and Milmine, McClure's, January 1907, pp. 230, 234.

- ^ Bates and Dittemore 1932, 7.

- ^ Fraser, 1999, p. 35.

- ^ Cather and Milmine, McClure's, January 1907, p. 236.

- ^ Bates and Dittemore 1932, p. 7.

- ^ Peel, 1966, p. 45.

- ^ Gill, 1998, pp. 39–47.

- ^ Mary Baker Eddy, Science and Health, 1st edition, Christian Science Publishing Company, 1875, 189–190.

- ^ (Retrospection and Instrospection, Copyright 1901, by Mary Baker G. Eddy, Copyright renewed 1929)

- ^ Cather and Milmine, McClure's, January 1907, p. 235.

- ^ Eddy, Retrospection and Introspection, 10.

- ^ Bates and Dittemore 1932, 16–17, 25.

- ^ Eddy, Retrospection and Introspection, 14–15

- ^ Cather and Milmine, McClure's, January 1907, p. 237.

- ^ Eddy, The First Church of Christ, Scientist, and Miscellany, 311: "My reply to the statement that the clerk's book shows that I joined the Tilton Congregational Church at the age of seventeen is that my religious experience seemed to culminate at twelve years of age. Hence a mistake may have occurred as to the exact date of my first church membership."

- ^ Eddy Retrospection and Introspection, 14

- ^ Gottschalk, pp. 62–64.

- ^ Gottschalk, 2006, 62–63.

- ^ Gill, 1998, pp. xxix, 68–69.

- ^ Gottschalk, 2006, p. 63.

- ^ Gill 1998, pp. 74–75.

- ^ Gottschalk, 2006, p. 64.

- ^ Eddy Retrospection and Introspection, 20.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Fraser 1999, 38.

- ^ "Women and the Law", Women, Enterprise & Society, Harvard Business School, 2010: "A married woman or feme covert was a dependent, like an underage child or a slave, and could not own property in her own name or control her own earnings, except under very specific circumstances. When a husband died, his wife could not be the guardian to their under-age children."

- ^ Jump up to: a b Gill, 1998, pp. 86–87.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Eddy, Retrospection and Introspection, 20–23.

- ^ Powell, 1930, pp. 95-96, 99.

- ^ Gill, 1998, p. 126.

- ^ Powell, 1930, p. 98

- ^ Gill, 1998, p. 127.

- ^ Gill, 1998, p. 131

- ^ Powell, 1930, p. 98.

- ^ Paul Buchanan. American Women's Rights Movement: A Chronology of Events and of Opportunities from 1600 to 2008. Branden Books, 2009. pp. 80–81.

- ^ Gill, 1998, pp.,133-135.

- ^ Frerichs, Ernest S. (ed.) The Bible and Bibles in America. Scholars Press, 1988, p. 196.

- ^ Milmine, 1909, p. 60.

- ^ Powell, 1930, p. 109

- ^ Peel, 1966, pp. 180-182.

- ^ Gill, 1998, p. 146.

- ^ Peel, 1966, pp. 181-183.

- ^ Fisher, 1929, p. 29.

- ^ H. A. L. Fisher, Our New Religion. London: Benn, 1929. pp. 27-29.

- ^ Knee, 1994, p. 7.

- ^ Gill, 1998, pp. 119-120.

- ^ Gill, 1998, p. 120.

- ^ Gill 1998, pp. 139, 144.

- ^ Gill, 1998, pp. 138-140.

- ^ Gill, 1998, pp. 140-141, 620.

- ^ Gill, 1998, pp. 138-141, 144.

- ^ Gill, 1998, p. 144.

- ^ Gill, 1998, p. 140.

- ^ Powell, 1930, pp. 107, 295.

- ^ Melton, J. Gordon. (1999). Religious Leaders of America: A Biographical Guide to Founders and Leaders of Religious Bodies, Churches, and Spiritual Groups in North America. Detroit: Gale Research. p. 175.

- ^ Edward H. Hammond (October 1899), "Christian Science: What It Is and What It Does", The Christian Science Journal, 17 (7): 464

- ^ Jump up to: a b Nenneman, 1997.[page needed]

- ^ Gill, 1998, pp. 161-170.

- ^ Eddy, Retrospection and Introspection, pp. 8–9, 22, 24–5.

- ^ Eddy, Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures, 143:5, 367:3.

- ^ Frank Podmore, Mesmerism and Christian Science: A Short History of Mental Healing, George W. Jacobs and Company, 1909, 262, 267–268.

- ^ Peel 1966, p. 133.

- ^ Gill, 1998, p. 627.

- ^ Gill, 1998, pp. 179–180.

- ^ Sibyl Wilbur, "The Story of the Real Mrs. Eddy," Human Life, March 1907, 10.

- ^ Wortham, p. 220.

- ^ Gardner 1993, 26.

- ^ Gardner 1993, 25.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Dakin, p. 56.

- ^ Gill, 1998, p. 172.

- ^ Gill, 1998, p. 173.

- ^ Gill, 1998, p. 174.

- ^ Peel, 1966, pp. 210-211.

- ^ Cather and Milmine, McClure's, May 1907, p. 108.

- ^ Cather and Milmine 1909, pp. 64–68, 111–116.

- ^ Cather and Milmine, 1909. Also see Robert Hall, The Modern Siren, H. L. Thatcher, 1916 (archive.org).

- ^ Todd Leonard, Talking to the Other Side: a History of Modern Spiritualism And Mediumship: A Study of the Religion, Science, Philosophy and Mediums that Encompass this American-Made Religion, iUniverse, Inc., 2005, 32-33

- ^ Christian Science versus Spiritualism Archived May 29, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Ann Braude, Radical Spirits: Spiritualism and Women's Rights in Nineteenth-Century America, Indiana University Press, 2001, 186.

- ^ Peel, 1977, p. 483, n. 104.

- ^ Gill, 1998, p. 324.

- ^ Beasley 1963, 83; Gill, 1998, p. 244.

- ^ Beasley 1963, 82; Koestler-Grack 2004, 52, 56.

- ^ Mary Baker Eddy Timeline

- ^ Gill, 1998, pp. 332–333.

- ^ Swami Prajnanananda, The Philosophical Ideas of Swami Abhedananada, Calcutta: Ramakrishna Vedanta Math, 1971, 164.

- ^ Maya Nanda, Vivekananda: His Gospel of Man-making with a Garland of Tributes and a Chronicle of his Life and Times, with Pictures, Swami Jyotirmayananda, 1993, 480; Timothy Miller, America's Alternative Religions, State University of New York, 1995, 174.

- ^ Damodar Singhal, Modern Indian Society and Culture, Meenakshi Prakashan, 1980, 136.

- ^ Wendell Thomas, Hinduism Invades America, The Beacon Press, Inc., 1930, 228–234 (archive.org).

- ^ Stephen Gottschalk, The Emergence of Christian Science in American Religious Life. University of California Press, 1973, pp. 152–153.

- ^ Eddy, Mary Baker The First Church of Christ, Scientist and Miscellany, page 119, line 10

- ^ Peel, 1971, p. 62.

- ^ Eddy, Church Manual of The First Church of Christ, Scientist, 1910, 17–18.

- ^ Eddy, Church Manual of The First Church of Christ, Scientist, 1910, 18–19.

- ^ Peel, 1971, pp. 81–82.

- ^ Peel, 1977, p. 483, n. 104.

- ^ Eric Caplan, Mind Games: American Culture and the Birth of Psychotherapy, University of California Press, 2001, 75.

- ^ A New Home," The Christian Science Journal, September 1888, 317.

- ^ See Christian Science Reading Room listings in current edition of the Christian Science Journal.

- ^ NOTES: Eddy, Manual of the Mother Church, 58.

- ^ Peel, 1977, p. 372.

- ^ Gill, 1998, p. xv.

- ^ Gill, 1998, p. 325.

- ^ Gill, 1998, p. 410.

- ^ Peel, 1977, p. 415, n. 121.

- ^ Beasley, 1963, p. 71.

- ^ Nenneman, 1997, p. 266.

- ^ Catherine L. Albanese (2007) A Republic of Mind and Spirit. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 290.

- ^ Jean Kinney Williams (1997) The Christian Scientists. New York: Franklin Watts. 42-43.

- ^ Jump up to: a b L. Ashley Squires (2017) Healing the Nation: Literature, Progress, and Christian Science. Indiana University Press. Kindle Edition.

- ^ Laurence Moore, Religious Outsiders and the Making of Americans, Oxford University Press, 1986.

- ^ Meehan 1908, 172-173; Beasley 1963, 283, 358.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Gill, 1998, pp. 207-208.

- ^ Gill, 1998, pp. 188, 192.

- ^ Gill, 1998, pp. 192, 201.

- ^ Gill, 1998, p. 202.

- ^ Miller 1995, 62.

- ^ John S. Haller, American Medicine in Transition, 1840-1910, 139.

- ^ Eugene Gallagher; Michael W. Ashcroft, Introduction to New and Alternative Religions in America, 93.

- ^ Gill 1998, 688-689.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Gill, 1998, p. 397.

- ^ Gottschalk, Stephen (2011) Rolling Away the Stone. Indiana University Press. 35.

- ^ Gill, 1998, p. 444.

- ^ Beasley 1963, 71: quoting Science and Health, 102.

- ^ William Williams, Encyclopedia of Pseudoscience: From Alien Abductions to Zone Therapy. Facts on File, 2000.

- ^ Mead, Frank S. (1995) Handbook of Denominations. 10th ed. Nashville, Tennessee: Abingdon Press, p. 106.

- ^ Christian Science: A Sourcebook of Contemporary Materials. Christian Science Publishing Society, 1990, pp. 107-108.

- ^ Moreman, Christopher M. (2013). The Spiritualist Movement: Speaking with the Dead in America and Around the World. Volume 1: American Origins and Global Proliferation. Praeger. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-313-39947-3

- ^ Springer, 1930, p. 299.

- ^ Gardner 1993.

- ^ Gill, 1998, p. 546.

- ^ Whorton 2004, 128.

- ^ Eddy, General Miscellany, 344–345.

- ^ Peel, 1977, pp. 108–109, 411, n. 65.

- ^ Peel, 1971, p. 376.

- ^ Arthur Brisbane, "An Interview with Mrs. Eddy," Cosmopolitan Magazine, August 1907.

- ^ Stark, 1988, pp. 189–214.

- ^ Erwin Canham. Commitment To Freedom: The Story of the Christian Science Monitor. Houghton Mifflin, 1958, pp. 14-15.

- ^ Bates and Dittemore 1932, 411, 413, 417.

- ^ 'Dr. Alan McLane Hamilton Tells About His Visit to Mrs. Eddy; After a Month's Investigdtion Famous Alienist Considers Leader of Christian Scientists "Absolutely Normal and Possessed of Remarkably Clear Intellect"'. The New York Times, August 25, 1907.

- ^ Anonymous. (1907). Mrs. Mary Baker Eddy’s Case of Hysteria. Journal of the American Medical Association 7: 614-615.

- ^ Karl Menninger, The Human Mind, Garden City Publishing Company, 1927, p. 84

- ^ Leon Saul and Silas Warner, The Psychotic Personality, Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1982, 287–288.

- ^ Wilson, Sheryl C; Barber, Theodore X. (1983). The Fantasy-Prone Personality. In Anees A. Sheikh. Imagery: Current Theory, Research and Application. New York: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 340-387.

- ^ George Vaillant. Ego Mechanisms of Defense: A Guide for Clinicians and Researchers. American Psychiatric Press, 1992, p. 70.

- ^ Ronald K. Siegel. Whispers: The Voices of Paranoia. Simon & Schuster, 1994, p. 105.

- ^ "Mrs. Eddy Dies of Pneumonia; No Doctor Near". The New York Times, December 5, 1910. "Mrs. Mary Baker Eddy, founder of the Church of Christ, Scientist, died Saturday night at 10:45 o'clock. The death was kept a secret until this morning, when a city medical examiner was called in. It was first publicly announced at the Mother Church this morning. Mrs. Eddy was in her ninetieth year."

- ^ "Mrs. Eddy's Life and Achievement," The Boston Globe, December 5, 1910, 4.

- ^ Collins, Keith S. (2012). The Christian Science Monitor: Its History, Mission, and People. Nebbadoon Press.

- ^ "Eddy Centenary Observed at Bow", The New York Times, July 16, 1921

- ^ Andrew W. Hartsook, Christian Science After 1910, Bookmark, 1994, 25–28.

- ^ "List of Markers by Marker Number" (PDF). nh.gov. New Hampshire Division of Historical Resources. November 2, 2018. Retrieved July 5, 2019.

- ^ "Mary Baker Eddy Historic Houses". Longyear Museum. Retrieved December 4, 2017.

- ^ Longyear Museum - Visitor Information Archived December 2, 2017, at the Wayback Machine for 23 Paradise Road, accessed 16 January 2017

- ^ Works by or about Mary Baker Eddy in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

Sources[]

- Ernest Sutherland Bates and John V. Dittemore. Mary Baker Eddy: The Truth and the Tradition. Knopf, 1932.

- Willa Cather, Georgine Milmine, et al. "Mary Baker G. Eddy". McClure's, December 1906 – June 1908.

- Edwin Franden Dakin. Mrs. Eddy: The Biography of a Virginal Mind. C. Scribner's Sons, 1929.

- Caroline Fraser. God's Perfect Child: Living and Dying in the Christian Science Church. Metropolitan Books, 1999.

- Martin Gardner. The Healing Revelations of Mary Baker Eddy. Prometheus Books, 1993.

- Gillian Gill. Mary Baker Eddy. Da Capo Press, 1998.

- Stephen Gottschalk. Rolling Away the Stone: Mary Baker Eddy's Challenge to Materialism. Indiana University Press, 2006.

- Richard A. Nenneman. Persistent Pilgrim: The Life of Mary Baker Eddy. Nebbadoon Press, 1997.

- Robert Peel. Mary Baker Eddy: The Years of Discovery. Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1966.

- Robert Peel. Mary Baker Eddy: The Years of Trial. Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1971.

- Robert Peel. Mary Baker Eddy: The Years of Authority. Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1977.

- Fleta Campbell Springer. According to the Flesh: A Biography of Mary Baker Eddy. Coward-McCann, 1930.

- Rodney Stark, "The Rise and Fall of Christian Science", Journal of Contemporary Religion, 13(2), 1988.

- Hugh Evelyn Wortham. Three Women: St. Teresa, Madame de Choiseul, Mṛṣ Eddy. Little, Brown and Company, 1930.

Further reading[]

- Samuel P. Bancroft. Mrs. Eddy as I Knew Her in 1870. Geo H. Ellis Co, 1923.

- Norman Beasley. The Cross and the Crown: The History of Christian Science. Duell, Sloan and Pearce, 1952.

- Norman Beasley. Mary Baker Eddy. New York: Duell, Sloan, and Pearce, 1963.

- Julie Berliet. Mary Baker Eddy. Paris: Messageries Coopératives Du Livre et De La Presse, [ca. 1936].

- Charles S. Braden. Christian Science Today: Power, Policy, Practice. Southern Methodist University Press, 1958.

- Arthur Brisbane. Mary Baker G. Eddy. Ball, 1908.

- Henrietta Buckmaster. Women Who Shaped History. Collier Books, 1966.

- Adam H. Dickey. Memoirs of Mary Baker Eddy. Robert G. Carter, 1927.

- Mary Baker Eddy Library. In My True Light and Life: Mary Baker Eddy Collections. Boston: The Writings of Mary Baker Eddy, 2002.

- James Franklin Gilman. Painting a Poem: Mary Baker Eddy and James F. Gilman Illustrate Christ and Christmas. Boston: Christian Science Publishing Society, [ca. 1997].

- Isabel Ferguson and Heather Vogel Frederick. A World More Bright: The Life of Mary Baker Eddy. Christian Science Publishing Society, 2013.

- Heather Vogel Frederick. Life at 400 Beacon Street: Working in Mary Baker Eddy’s Household. Chestnut Hill: Longyear Museum Press, 2019.

- Yvonne Cache von Fettweis and Robert Townsend Warneck. Mary Baker Eddy: Christian Healer. Christian Science Publishing Company, 1998.

- Doris Grekel. The Discovery of the Science of Man: The Life of Mary Baker Eddy (1821–1888). Healing Unlimited, 1999.

- Doris Grekel. The Founding of Christian Science: The Life of Mary Baker Eddy (1888–1900). Healing Unlimited, 1999.

- Doris Grekel. The Forever Leader: The Life of Mary Baker Eddy (1901–1910). Healing Unlimited, 1999.

- Robert A. Hall. The Modern Siren. New York, 1916.

- Ella H. Hay. A Child's Life of Mary Baker Eddy. Boston, Christian Science :Publishing Society, [ca. 1942].

- Walter M. Haushalter. Mrs. Eddy Purloins from Hegel. Beauchamp, 1936.

- Kenneth Hufford. Mary Baker Eddy and the Stoughton Years. Longyear Foundation, [ca. 1963].

- Hugh A. Studdert Kennedy. Mrs. Eddy as I Knew Her: Being Some Contemporary Portraits of Mary Baker Eddy, the Discoverer and Founder of Christian Science. The Farallon Press, 1931.

- Stuart E. Knee. Christian Science in the Age of Mary Baker Eddy.. Greenwood Press, 1994.

- Marian King. Mary Baker Eddy: Child of Promise. Prentice-Hall, Inc., [ca. 1968].

- Rachel A. Koestler-Grack. Mary Baker Eddy. Facts On File, 2004.

- William Lyman Johnson. The History of The Christian Science Movement by Contemporaneous Authors, Written For and Edited at the Request of Mary Beecher Longyear. The Zion Research Foundation, 1926. 2 Vols.

- Julia Michael Johnston. Mary Baker Eddy: Her Mission and Triumph. Boston: Christian Science Publishing Society, [ca. 1946].

- Paul Lomaxe. Mary Baker Eddy: Spiritualist Medium. General Assembly of Spiritualists, 1946.

- Myra B. Lord. Mary Baker Eddy: A Concise Story of Her Life and Work. Davis & Bond, 1918. (archive.org)

- Walter Ralston Martin. The Christian Science Myth. Zondervan Publishing House, 1955.

- Michael Meehan, Mrs. Eddy and the Late Suit in Equity. 1908.

- Georgine Milmine. archive.org The Life of Mary Baker G. Eddy and the History of Christian Science, Doubleday, Page & Company, 1909. Also published as Willa Cather and Georgine Milmine. The Life of Mary Baker G. Eddy and the History of Christian Science. University of Nebraska Press, 1993.

- Conrad Henry Moehlman. Ordeal by Concordance: An Historical Study of a Recent Literary Invention." Longmans Green & Co., 1955.

- William Dana Orcutt. Mary Baker Eddy and her Books." Boston: Christian Science Publishing Society, [1950.]

- Frederick W. Peabody. Complete Exposure of Eddyism or Christian Science: The Plain Truth in Plain Terms Regarding Mary Baker G. Eddy. 1904 [1901].

- Frederick W. Peabody. The Religio-Medical Masquerade: A Complete Exposure of Christian Science. Revell, 1910 and 1915.

- Lyman Pierson Powell. Christian Science: The Faith and Its Founder. G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1907.

- Lyman Pierson Powell. Mary Baker Eddy: A Life Size Portrait. MacMillan, 1930. (Reprinting: The Christian Science Publishing Society, 1930, 1950, 1991.

- Cindy Peyser Safronoff. Crossing Swords: Mary Baker Eddy vs Victoria Clafin Woodhull and the Battle for the Soul of Marriage - The Untold Story of America's Nineteenth-Century Culture War. this one thing, 2015.

- Julius Silberger. Mary Baker Eddy, An Interpretive Biography of the Founder of Christian Science. Little, Brown, 1980.

- Jewel Spangler Smaus. Mary Baker Eddy: The Golden Days. Christian Science Publishing Society, 1966.

- Clifford P. Smith. Historical Sketches from the Life of Mary Baker Eddy and the History of Christian Science. Christian Science Publishing Society, 1934. [1941, 1969]

- Louise A. Smith. Mary Baker Eddy. Chelsea House Publishers, [ca. 1991].

- James H. Snowden. Truth About Christian Science the Founder and the Faith. 1920.

- David Thomas. With Bleeding Footsteps: Mary Baker Eddy's Path to Religious Leadership. Knopf, 1994.

- Irving C. Tomlinson. Twelve Years with Mary Baker Eddy. Christian Science Publishing Society, 1945.

- Mark Twain.Christian Science. Harper, 1907 (archive.org).

- Amy B. Voorhees. A New Christian Identity: Christian Science Origins and Experience in American Culture. University of North Carolina Press, 2021.

- Peter Wallner. Faith on Trial: Mary Baker Eddy, Christian Science and the First Amendment. Plaidswede Publishing, 2014.

- Sibyl Wilbur. The Life of Mary Baker Eddy. The Christian Science Publishing Society, 1907.

- Stefan Zweig. Die Heilung durch den Geist: Mesmer, Freud, Mary Baker Eddy. 1932. (Mental Healers: Franz Anton Mesmer, Mary Baker Eddy, Sigmund Freud, Viking, 1932).

External links[]

- Mary Baker Eddy Library

- Mary Baker Eddy and Basic teachings of Christian Science, christianscience.com

- The Longyear Museum

- Works by Mary Baker Eddy at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Mary Baker Eddy at Internet Archive

- Works by Mary Baker Eddy at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Mary Baker Eddy at Find a Grave

- Norwood, Arlisha. "Mary Eddy". National Women's History Museum. 2017.

- 1821 births

- 1910 deaths

- 19th-century American writers

- 19th-century American women writers

- 20th-century American writers

- 20th-century American women writers

- American abolitionists

- American Christian religious leaders

- American Christian Scientists

- American feminists

- Burials at Mount Auburn Cemetery

- Christian Science writers

- Deaths from pneumonia

- Christian feminist theologians

- Founders of new religious movements

- Infectious disease deaths in Massachusetts

- People from Lynn, Massachusetts

- People from Bow, New Hampshire

- People from Swampscott, Massachusetts

- People in alternative medicine

- Religious leaders from Massachusetts

- Religious leaders from New Hampshire

- Writers from New Hampshire

- Women religious writers

- Activists from New Hampshire

- People from Tilton, New Hampshire

- Christian abolitionists

- The Christian Science Monitor people

- Mary Baker Eddy