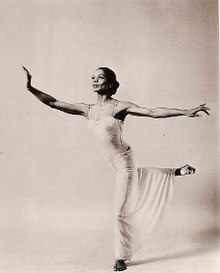

Mary Hinkson

This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2020) |

This article may require copy editing for "you", contractions. (August 2021) |

Mary De Haven Hinkson | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Mary De Haven Hinkson March 16, 1925 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania |

| Died | November 26, 2014 (aged 89) New York, New York |

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | University of Wisconsin |

| Occupation | Dancer, choreographer |

| Spouse(s) | Julien Jackson; 1 child |

Mary De Haven Hinkson (March 16, 1925 – November 26, 2014) was an African American dancer and choreographer known for breaking racial boundaries throughout her dance career in both modern and ballet techniques. She is best known for her work as a member of the Martha Graham Dance Company.

Personal life[]

Hinkson was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania in 1925 to a mother and father who worked as a public school teacher and physician/first African American head of an army hospital, respectively.[1][1][2] Hinkson studied Dalcroze technique in a high school eurythmics class, as well as Native American dance forms at summer camp.[3] Due to not being taken seriously as a living room dancer, she did not receive formal dance training until enrolling at the University of Wisconsin, where she eventually studied with Margaret H'Doubler. During her summers at camp, she was most excited to be taught by and was truly set on fire for dance. Despite the fact that she “didn't even know what a plie was,” she was pushed to begin pointe work.[4]

While she attended high school at Philadelphia High School for Girls, a very traditional school who taught Latin and not contact sports, she learned formalized gymnastics and participated in competitions. Until she was able to gain proper training, this is what she assumed dance was.[5]

In 1958, she and her husband Julien Jackson had their only child, a daughter, Jennifer.

She died of pulmonary fibrosis in Manhattan in 2014, aged 89.[6]

Education[]

When she began college at the University of Wisconsin, she was thrown into situations she was uncomfortable and inexperienced in such as basketball and soccer.[7] Other courses she took included “English, French, history, zoology, and PE,” all of which she excelled and received A's and B's in.[8] Thankfully, the university was one of the first to have a real dance major which Hinkson abandoned all of her previous credits to join.[9]

, the head of the dance department, had a love for kinesthetic awareness and teaching scientifically which she shared by teaching her students how to test the limits of their bodies. One exercise Hinkson recalled was creating movement on the floor while blindfolded and then recreating it while standing for it to eventually piece together into a phrase. Mary loved learning under her and the ways she coaxed out their individuality.[10]

While at University of Wisconsin, Hinkson also learned from Louise, a technique teacher trained by Mary Wigman and Hanya Holm. She moved in an internal and lyrical style and taught primarily from Holm's technique. Even though HInkson never saw Louise fully dance, she knew it was exquisite from the way she took up so much space pacing the front of their enormous studio.[11]

One of the experiences Hinkson learned through was by joining , a dance group that required an audition to get into. She was quite intimidated by the obvious experience the other dancers had, but made it into the group nonetheless. During her first performance with them in Orpheus and Eurydice, a local afro-american paper cited her and Matt Turney, who became lifelong friends, as being the first African American members.[12] Orpheus and Eurydice was the piece that brought Mary to a real stage for the very first time, allowing her to feel concentration and the warmth of the lights like never before. Her teacher Louise remarked on the powerful projection she had during this performance, which was a great accomplishment for her considering the anxiety and fickleness that often caused her to skip out on rehearsals. After that, she didn't feel the same nerves about dancing in the theater again.[13]

Mary graduated in 1946 and continued studying in graduate courses for a year before ending up as an instructor for the “Department of Physical Education for Women — one of the first black women to teach at any majority-white university”.[14]

During her time at University of Wisconsin, Hinkson dealt with segregation and discrimination. Although African American students were allowed to enroll, they were often excluded from school events and barred from most dormitories and close rooming houses. Hinkson and Matt Turney lived at the Groves Women's Cooperative during their time at school.[15]

Career[]

It was at H'Doubler's encouragement that she first saw the Martha Graham Dance Company when they performed in Wisconsin in the 1940s.[16]

During their junior and senior year, Mary and a few other students (Matt Turney, Miriam Cole, Sage Fuller Cowles) formed the Wisconsin Dance Group, got an old car, and travelled around the country booking performances and doing dances they choreographed.[17] Mary was not the largest contributor to choreography due to her lack of experience, but their pieces were received very well. To keep the car running well, all of the dancers had to chip in $15 for gas and maintenance before paying themselves. They continued this after graduating.[18]

Wanting to further their careers, they moved to New York hoping to train in Hanya's vein of work but found she was not teaching as much. They were unsure how to study dance, so they decided to concentrate at the Grand Studio.[19]

After seeing Hinkson and Turney's talent and hearing who their teacher was, Hinkson was selected to perform in a 1951 demonstration by Martha Graham. This demonstration included works from , Diversion of Angels, and Sarabande. Hinkson even filled in for a larger role when it was left empty and performed with Bertram Ross. After this performance, her talents were recognized by Martha Graham and she was asked to join the Martha Graham Dance Company, which was sponsored by the B. de Rothschild Foundation and opened April 13, 1953 at the Alvin Theater. She continued to work with the company and even joined one of YURIKO's experimental classes.[20]

During Hinkson's first official season as a part of the company in 1952, Graham choreographed a role especially for her in . For the 9 AM rehearsals, Hinkson would go back and forth between the studio and where she lived at International House by Juilliard. While she was rehearsing, Graham made Hinkson go out and get her own Dogwood branches for prop use during the role, which she found to be extensive and difficult. She recalled an idea Graham told her regarding commitment to the role- “You must take responsibility for your own role. If it's to be meaningful you must dress your hair, think how you're going to dress your hair... you have to participate.” Later when it came time to revive this piece, Graham resisted it.[21]

In her early career, Hinkson struggled with lack of parental approval and money, sometimes only having $5 to her name. She made money by giving private lessons and learning to teach for an eventual career as a teacher at Juilliard School of Music, Dance Theatre of Harlem, and the . In the early days of building up to this position, she was to demonstrate for eight weeks and lead an introductory course before moving up the food chain towards teaching company classes. When demonstrating for Graham, Hinkson would be verbally instructed in the moment as to what she should be doing and sometimes took a little bit longer to catch on. Hinkson didn't particularly enjoy the process and felt that it didn't provide a great understanding of what it meant to be an instructor. A maximum of 25 students were enrolled in each class.[22]

Hinkson had periods where she worked with the New York City Opera. When she stopped at the drugstore on the way to her audition, she noticed a tall man in an aviator suit with a big dog. It turned out that this man was John Butler, the one she was auditioning for. She was selected to join the opera, but found out later that Butler had mixed up Mary Hinkson and Matt Turney and didn't actually ask to see Hinkson audition. Mary found working at the Opera to be a much more professional and reliable environment compared to the Martha Graham Dance Company. In comparing the two, she said, “There was none of this chaos that we always had. You know, we’re in the company where we aren't ever told what you're gonna dance, we weren't given a contract, we weren't this, we weren't that, and if you dared to ask you were being insolent.” Between the years 1952 and 1953, Butler regularly took the opera to perform at the NBC Sunday morning shows for thirty minute time slots. The dancers became so practiced that they would do their makeup themselves before arriving on set. Sometimes during their rehearsals, Doris Humphrey would even come to watch and critique them. Hinkson had a wonderful time balancing both companies, but sometimes Graham, who was very dedicated to her patterns and methods and could be seen as uncompromising, would become upset at Butler for conflicting schedules.[23]

Hinkson achieved the title of principal dancer in Bluebeard’s Castle at the New York City Opera in 1953. She found the dance to be kind of frightening because she was lifted into the air a lot while standing on a 12 foot platform. Additionally, she was asked to audition for Balanchine's Figure in the Carpet in 1960. Although she was in many productions, she was not able to attend the company's Asian tour in 1956 because of her wedding that year.[24]

In 1953, Hinkson stepped into the role of woman in white in Heretic when it was left empty. She worried about not being able to live up to the reputation of the previous woman in white. Yuriko comforted her by reminding her to make the role her own and not constrict herself because of someone else's abilities. warned Hinkson not to get destroyed by the part like everyone else who played it. When Graham would not rechoreograph a particularly difficult knee drop for Hinkson, Yuriko helped her replace the movement. For a short time, Hinkson wore a pale pink for this role, but it was changed back to white after being referenced as “underwear pink” by a critic.[25]

They then went on tour to Europe from February to June and travelled by boat, something that was uncommon for dance companies. The whole group had a fun time playing charades and games all together, which irked a sea sick Graham. During their practices on tour, Graham worked them to death in the freezing cold weather, which made them take great advantage of the sometimes long and luxurious breaks in between rehearsals.[26]

During their time in England, Graham almost cancelled a premiere because of an unfinished piece. Their producer would not let that happen, so Hinkson and the company had to work extra hard to improvise and fill in the blanks which gave them a lot of practice at thinking on their feet. They left England after three weeks with poor reviews, which Hinkson felt was partly due to the audience not seeing past Graham's more mature age to the performer side of her.[27]

The company was very excited to arrive in Holland as it was much warmer there. The audience reaction was also vastly different; at times the police had to hold back the crowds pushing to get in. They performed in lecture/demonstration formats doing pieces like , Appalachian Spring, Diversion of Angels and . Hinkson was in many of these pieces, but also had the chance to watch some of them from the front with Turney.[28]

Hinkson returned in August after staying in Europe to travel a little longer. She was enticed to stay by friends she made in Jack Cole’s company and the refreshing days they had together, but ended up coming back to New York. Martha wanted everyone to go on tour again to the far east, but Hinkson refused to go. The company was gone from the end of 1955 to 1956.[29]

In 1955, Hinkson participated in , a work that was a series of solos. Although she did learn the role of the martyr, she was placed in the role of the warrior late in the process as she was replacing . The solo was very militant and full of jumping, but Hinkson “made it more fragile and human and feminine and that she deeply feared what she had to do.” Although Graham usually would adapt roles to the dancer, she stayed true to her vision for this one at the time. The rest of the production was even rushed; Hinkson remembers the day they performed: ”Jessica was sewing seams on me in the wings when the music was playing and the curtain was up, so I went out there like I was shot out of the cannon.” Later, the dancers performed in plain and uniform costumes so their performances rather than their outfits would be judged. Eventually, the roles were rearranged as the dance continued to be performed into the future, but the role of the warrior as Mary knew it was gone and changed. She did not perform as the warrior again as it went to other dancers instead.[30]

When Hinkson returned to in 1958, she stepped into the lyrical role of the maid, which was taught to her by the original maid, Patsy. In order to make sure she differentiated this role from all of the other ones she learned in the piece, she made sure to step outside of the stereotypes and not play into them too much. Hinkson tried “to try to work for a real frightened innocent element in the section leading up to the maid, which is what that solo has. And before the warrior, a combination of things. The terror that she felt combined with the power.”[31]

Hinkson took on this role when she didn't expect to. Originally declining to go with the company on a tour to Israel to stay with her daughter, Graham persuaded her to go when one of the dancers became unexpectedly pregnant. She left her daughter with her mother for 6-7 weeks while she was gone- which her mother didn't approve of her doing- and used the tour to conquer her fear of not living up to the dancers before her. Due to this obstacle and the challenges of rechoreographing, Hinkson much prefers having a piece done specifically for her.[32]

Some of the more unrewarding roles Hinkson held were that of Athena and Iphigenia in Clytemnestra. She had difficulty connecting to the piece as well as didn't much prefer all of the sitting and watching it included. Doing the Furies dance was a much more enjoyable experience for her. And although the ending was altered later, the original one with some of the cast walking forward holding a stoll above their head had an incredible dark and continuing effect. When learning the role of Iphigenia, she was taught by Yuriko, who had much more staccato and quick movement. As Hinkson does not share this style, she comparatively enjoyed learning from better because she is much more about musicality like herself.[33]

When she learned the role of , her and Graham worked off of films; they had to grapple with them in order to get over the challenges of the movements being mirrored, the film being sped up, and the music being silenced. It took the quick playing of their pianist to help them put the movement to the soundtrack. They also had difficulty adapting to the tweaks Graham made to the choreography over the years. Hinkson relied on notes scribbled in the margins of the sheet music to piece it together. To put together the heart of the character, Hinkson drew a line between who she was supposed to be at the beginning of the piece versus the end so she could showcase everything.[34]

In regards to performing as Madea in Cave of the Heart, she said, “We must realize that it's a woman scorned, but first she was a woman in love. So to play Madea as a witch from the moment the curtain pulled up would miss the whole point.” It was also a struggle to learn this piece off of film as they had no notes scribbled on the sheet music. Mary was able to get very emotionally involved in the dance, although she was only able to perform it twice. She did earn a compliment from Martha, however, for how she used the music.[35]

Hinkson performed as Eve in in 1958 with Bertram Ross as Adam and eventually performed as Lilith opposite ’s Adam. She learned in this piece that you cannot take some roles too seriously or you will not be able to fully explore and hit the mark. She said, “You have to dance it more than be like ‘I'm going to be dramatic.’ I think you have to dance it, really dance it, go with it, and give it flight.”[36]

During one season performing , Graham implemented alternates and made Hinkson one of them. Yuriko, Mary Hinkson, and the other alternate Linda were affectionately called “the three faces of eve” by Bertram Ross. Using this system was a rare circumstance, however, as Graham was not physically involved at times so having to coordinate so many people would be a pain for her. The downside of being an alternate was getting the short end of the stick during rehearsal time.[37]

Graham choreographed a role specifically for Hinkson in Circe, something that had not happened since . Graham used this as a bribe to get Hinkson to go on tour with them again as she was hesitant to leave her daughter; the bribe worked and she went on tour with them. Martha Graham had originally intended the role for herself before it was Hinkson's, but remained very close to the story and performance that she put on. Hinkson learned the character based on the images that Graham gave her regarding the animalistic and oblique nature of the movement. She tried to give her performance “the senses to associate with an animal rather than an intellectual thought out plot or scheme” yet make her a deceitful enchantress. Playing the role of Circe helped Hinkson learn how to play off of and show her connections to the other performers. During rehearsals for Circe, she noted that Graham began a period of unreliability and was not as present. When it was finally put on the stage, Yuriko helped Hinkson create a memorable head piece by sweeping up her hair with much spray and a looped gold wire. It was such a complicated head piece that she was unable to perform in other pieces after it during shows.[38]

Circe premiered in London. It was not completely finished for the first showing, so Hinkson and the rest of the company were in hysterics finishing costumes and choreography last minute. The audiences loved the piece. The piece came alive onstage in a way it never did during rehearsal because Hinkson realized they had to rely on their own animal instinct and let it be as dramatic as possible.[39]

Hinkson took classes in many places, one of which was with Louis Horst. He enjoyed her so much that he travelled her around to demonstrate for him at many places, some of which being high school performing arts programs. Hinkson, Bertram Ross, and took charge of spearheading the . They worked off of old films for the duos, but when reconstructing the solos they relied on Yuriko’s memory for help. When Hinkson first saw Dark Meadow as a spectator the concept went right over her head, but performing it gave it a whole new life and meaning for her: “It was as though I had been put in touch with some unknown ancestors or something. It was a remarkable experience and it was very ritualistic but to perform it is like going through a very true, a kind of ritual where it's as if a human being is emerging through a ritual experience and you're going way way way back in time to find out who you are.” Despite her love for the overall experience, Hinkson had to work extra hard to embody her character because she was not playing a specific person like she usually does, instead having to flesh out the details for herself by searching for herself through the ritual. The hardest part of this, Hinkson thought, was making sure the dance is still more than just a dance. Overall, this piece and the music was an almost religious experience for Hinkson as well as a great challenge.[40]

Hinkson also danced in Deaths and Entrances, which she remembers most for the way her relationship with Graham grew during rehearsals. It was a tough piece and although Hinkson made many strides, it still looked shaky for a while. They premiered it at the Blossom Festival with the Cleveland Symphony Orchestra live.[41]

Out of all her roles, Hinkson liked the ones that had the most continuity in the performance. When there were constant starts and stops in a piece, she found that it was not as fulfilling to perform. In , there were breaks in the dancing but everyone was always somehow involved in the action. In Diversion of Angels it is a bit more fragmented, but Hinkson still considered it nonstop. In Circe, dancers are on stage all the time and in almost everything. In , it is not the most satisfying because there are moments of stop where they must pose uncomfortably. “There's no denying that the best training in the world is to actually perform,” Mary said, and she was able to gain this experience over the course of her career. “Each thing in a certain way contributes in some way.”[42]

Hinkson performed in many pieces. These include , Clytemnestra, Deaths and Entrances, Cave of the Heart, , Seven Deadly Sins (commissioned by Queen Elizabeth's Theater), , , , Carmina Burana, , The Figure in the Carpet, Secular Games and Circe.[citation needed]

Leaving the Company[]

It was not a single event but a large accumulation of instances that brought on Hinkson leaving the company. It began with an 18-month period of Graham sulking, drinking, and miscommunicating. Hinkson and Bertram Ross didn't want the company to fall by the wayside, so they took it upon themselves to grow their numbers and pour into their programs. They faked “the malady of the seventies where [they] held these auditions and had these young people come in, offered them 100 dollars a week for their services.” They hoped to instill in them a sense of hard work and it was rewarding to see some of them do well, although many were not very committed. While Graham was away, in and out of the hospital, or secluded, Hinkson and Ross would visit her and talk about everything other than the company. Graham never acknowledged the existence of the program to Hinkson's face.[43]

After they finished the last series of works, Hinkson visited Europe in summer of 1972 and had surgery for her torn meniscus. When she returned, Graham wanted to plot the downfall of some of the head figures at the company and bring Hinkson and Turney in on it, which they did not want to do. In the meantime, new associate director Ron Protas came out of nowhere and attached himself rather quickly to Graham.[44]

The next conflict was over the presentation of the Martha Graham Dance Company on a mixed bill. This went against what Graham had always done, so she accused Hinkson of trying to send her down the river. She removed the company from the event which had repercussions for both them and the City Center.[45]

As part of the endeavor to widen their reach, the company toured to multiple schools. After an error with the earnings records, Graham began pointing fingers. No legal accusations were made and it was cleared up, but she did not forget it.[46]

Hinkson then took some of the new dancers and left on a residency. She was able to share positive moments with Graham over the phone as they discussed the different performances they did and their thoughts on them. This residency as well as their spring broadway opportunities were heavily publicized by .[47]

It got more and more difficult to work with Ron Protas who fired people, kept Hinkson from Graham, sabotaged her effort to build a good relationship with one of her residencies, and mismanaged the work usually done for performances and teaching opportunities. He attempted to get everyone to go on tour again, but after Hinkson heard it was triple cast, she realized she would much rather stay in New York and teach.[48]

After Bertram Ross told her that he was handing in his resignation, Hinkson went straight to Graham who was hardly present and mostly on pain medication. She said, “I was wanting out only I had not totally come to grips with it. The situation was unbearable.”[49]

As the situation escalated and Hinkson's time at the company was hanging on by a thread, she was promised that Bertram Ross would be hired back for her and their contracts could be signed on the same day. When hers was not ready as promised and Graham scolded Hinkson for it, they had a big argument and Hinkson left the Martha Graham Dance Company at 48 years old. She did not look back and was glad she lifted that weight off her shoulders.[50]

In regards to her time at the company, “It was never a bed of roses to work there but at least you always had this belief, this respect for the end product and theater experience.”[51] It was the loss of this that fueled her departure. Even though she ended on a bad note, she felt that her earlier knee injury gave her more appreciation for the gift it was to be there for a time. To keep dance in her life, she continued to teach and contribute to smaller performances.[52]

Choreography[]

Over the course of her career, Hinkson worked with many well known dancers and choreographers. Some of them are Harry Belafonte, Alvin Ailey, Pearl Lang, Walter Nix, John Butler, Martha Graham, Glen Tetley, and Merce Cunningham.[53]

Working with Tetley was different than other choreographers. He didn't often require dancers to improvise so he could get inspiration, he initiated ideas without imposing dynamics or quality. Working with him was challenging but still pleasurable. Mary often dreaded the practices at Graham's company, but woke up inspired for laughter filled rehearsals with Tetley. His movement was more about implication than anything, but he still asked for drama.[54]

She also taught at Juilliard School of Music, Dance Theatre of Harlem, and the .

Relationship with Martha Graham[]

Hinkson and Martha Graham’s relationship had its ups and downs. At their best, they had meaningful rapport during rehearsals and choreography sessions and sometimes Martha gave Hinkson a rare compliment on her movement. Other times, they fought over rechoreographing and Hinkson's endeavors outside of the company. She appreciated Graham's talent, wisdom, and process, but at times did not like the way she spoke to her. Hinkson mostly tolerated their spats, but at times would retaliate with her own attitude. In response to Hinkson taking other opportunities or standing up for herself, Graham would often yell at her or limit her from participating in certain works.[55]

Notes[]

- ^ Long, Harvey. "UW-Madison Dance Revolutionary Mary Hinkson". University of Wisconsin-Madisn=on. Retrieved September 27, 2020.

- ^ "Mary Hinkson". Notable Black American Women. Biography in Context. Gale. Retrieved May 12, 2014.

- ^ Eichenbaum, Rose (2008). The Dancer Within: Intimate Conversations with Great Dancers. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press. p. 65.

- ^ Nutchtern, Jean.”Interview with Mary Hinkson.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. N.p. 1976. Oral Histories (web). September 9, 2020. [1].

- ^ Nutchtern, Jean.”Interview with Mary Hinkson.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. N.p. 1976. Oral Histories (web). September 9, 2020. [2].

- ^ Obituary, nytimes.com, November 30, 2014; accessed December 1, 2014.

- ^ "UW-Madison Dance Revolutionary Mary Hinkson". Diversity, Equity & Inclusion. 2020-02-28. Retrieved 2021-08-02.

- ^ Long, Harvey. "UW-Madison Dance Revolutionary Mary Hinkson". University of Wisconsin-Madisn=on. Retrieved September 27, 2020.

- ^ Nutchtern, Jean.”Interview with Mary Hinkson.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. N.p. 1976. Oral Histories (web). September 9, 2020. [3].

- ^ Nutchtern, Jean.”Interview with Mary Hinkson.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. N.p. 1976. Oral Histories (web). September 9, 2020. [4].

- ^ Nutchtern, Jean.”Interview with Mary Hinkson.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. N.p. 1976. Oral Histories (web). September 9, 2020. [5].

- ^ Long, Harvey. "UW-Madison Dance Revolutionary Mary Hinkson". University of Wisconsin-Madisn=on. Retrieved September 27, 2020.

- ^ Nutchtern, Jean.”Interview with Mary Hinkson.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. N.p. 1976. Oral Histories (web). September 9, 2020. [6].

- ^ Long, Harvey. "UW-Madison Dance Revolutionary Mary Hinkson". University of Wisconsin-Madisn=on. Retrieved September 27, 2020.

- ^ Long, Harvey. "UW-Madison Dance Revolutionary Mary Hinkson". University of Wisconsin-Madisn=on. Retrieved September 27, 2020.

- ^ Eichenbaum, Rose (2008). The Dancer Within: Intimate Conversations with Great Dancers. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press. p. 65.

- ^ Long, Harvey. "UW-Madison Dance Revolutionary Mary Hinkson". University of Wisconsin-Madisn=on. Retrieved September 27, 2020.

- ^ Nutchtern, Jean.”Interview with Mary Hinkson.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. N.p. 1976. Oral Histories (web). September 9, 2020. [7].

- ^ Nutchtern, Jean.”Interview with Mary Hinkson.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. N.p. 1976. Oral Histories (web). September 9, 2020. [8].

- ^ Nutchtern, Jean.”Interview with Mary Hinkson.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. N.p. 1976. Oral Histories (web). September 9, 2020. [9].

- ^ Nutchtern, Jean.”Interview with Mary Hinkson.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. N.p. 1976. Oral Histories (web). September 9, 2020. [10].

- ^ Nutchtern, Jean.”Interview with Mary Hinkson.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. N.p. 1976. Oral Histories (web). September 9, 2020. [11].

- ^ Nutchtern, Jean.”Interview with Mary Hinkson.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. N.p. 1976. Oral Histories (web). September 9, 2020. [12].

- ^ Nutchtern, Jean.”Interview with Mary Hinkson.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. N.p. 1976. Oral Histories (web). September 9, 2020. [13].

- ^ Nutchtern, Jean.”Interview with Mary Hinkson.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. N.p. 1976. Oral Histories (web). September 9, 2020. [14].

- ^ Nutchtern, Jean.”Interview with Mary Hinkson.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. N.p. 1976. Oral Histories (web). September 9, 2020. [15].

- ^ Nutchtern, Jean.”Interview with Mary Hinkson.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. N.p. 1976. Oral Histories (web). September 9, 2020. [16].

- ^ Nutchtern, Jean.”Interview with Mary Hinkson.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. N.p. 1976. Oral Histories (web). September 9, 2020. [17].

- ^ Nutchtern, Jean.”Interview with Mary Hinkson.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. N.p. 1976. Oral Histories (web). September 9, 2020. [18].

- ^ Nutchtern, Jean.”Interview with Mary Hinkson.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. N.p. 1976. Oral Histories (web). September 9, 2020. [19].

- ^ Nutchtern, Jean.”Interview with Mary Hinkson.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. N.p. 1976. Oral Histories (web). September 9, 2020. [20].

- ^ Nutchtern, Jean.”Interview with Mary Hinkson.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. N.p. 1976. Oral Histories (web). September 9, 2020. [21].

- ^ Nutchtern, Jean.”Interview with Mary Hinkson.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. N.p. 1976. Oral Histories (web). September 9, 2020. [22].

- ^ Nutchtern, Jean.”Interview with Mary Hinkson.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. N.p. 1976. Oral Histories (web). September 9, 2020. [23].

- ^ Nutchtern, Jean.”Interview with Mary Hinkson.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. N.p. 1976. Oral Histories (web). September 9, 2020. [24].

- ^ Nutchtern, Jean.”Interview with Mary Hinkson.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. N.p. 1976. Oral Histories (web). September 9, 2020. [25].

- ^ Nutchtern, Jean.”Interview with Mary Hinkson.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. N.p. 1976. Oral Histories (web). September 9, 2020. [26].

- ^ Nutchtern, Jean.”Interview with Mary Hinkson.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. N.p. 1976. Oral Histories (web). September 9, 2020. [27].

- ^ Nutchtern, Jean.”Interview with Mary Hinkson.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. N.p. 1976. Oral Histories (web). September 9, 2020. [28].

- ^ Nutchtern, Jean.”Interview with Mary Hinkson.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. N.p. 1976. Oral Histories (web). September 9, 2020. [29].

- ^ Nutchtern, Jean.”Interview with Mary Hinkson.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. N.p. 1976. Oral Histories (web). September 9, 2020. [30].

- ^ Nutchtern, Jean.”Interview with Mary Hinkson.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. N.p. 1976. Oral Histories (web). September 9, 2020. [31].

- ^ Nutchtern, Jean.”Interview with Mary Hinkson.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. N.p. 1976. Oral Histories (web). September 9, 2020. [32].

- ^ Nutchtern, Jean.”Interview with Mary Hinkson.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. N.p. 1976. Oral Histories (web). September 9, 2020. [33].

- ^ Nutchtern, Jean.”Interview with Mary Hinkson.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. N.p. 1976. Oral Histories (web). September 9, 2020. [34].

- ^ Nutchtern, Jean.”Interview with Mary Hinkson.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. N.p. 1976. Oral Histories (web). September 9, 2020. [35].

- ^ Nutchtern, Jean.”Interview with Mary Hinkson.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. N.p. 1976. Oral Histories (web). September 9, 2020. [36].

- ^ Nutchtern, Jean.”Interview with Mary Hinkson.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. N.p. 1976. Oral Histories (web). September 9, 2020. [37].

- ^ Nutchtern, Jean.”Interview with Mary Hinkson.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. N.p. 1976. Oral Histories (web). September 9, 2020. [38].

- ^ Nutchtern, Jean.”Interview with Mary Hinkson.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. N.p. 1976. Oral Histories (web). September 9, 2020. [39].

- ^ Nutchtern, Jean.”Interview with Mary Hinkson.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. N.p. 1976. Oral Histories (web). September 9, 2020. [40].

- ^ Nutchtern, Jean.”Interview with Mary Hinkson.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. N.p. 1976. Oral Histories (web). September 9, 2020. [41].

- ^ Nutchtern, Jean.”Interview with Mary Hinkson.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. N.p. 1976. Oral Histories (web). September 9, 2020. [42].

- ^ Nutchtern, Jean.”Interview with Mary Hinkson.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. N.p. 1976. Oral Histories (web). September 9, 2020. [43].

- ^ Nutchtern, Jean.”Interview with Mary Hinkson.” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. N.p. 1976. Oral Histories (web). September 9, 2020. [44].

Sources[]

This section lacks ISBNs for the books listed in it. (December 2014) |

- Allen, Zita. "A Conversation Between Two Dance Legends: Judith Jamison and Mary Hinkson", New York Amsterdam News, February 1, 2007.

- Eichenbaum, Rose, and Aron Hirt-Manheimer (eds.) The Dancer Within: Intimate Conversations with Great Dancers. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan UP (2008).

- "Interview with Mary Hinkson."

- Mary Hinkson Dances Way Toward Roadway by Tour", Pittsburgh Courier; accessed July 5, 2013.

- Mary Hinkson profile, ENCYCLOPEDIA OF AFRICAN-AMERICAN CULTURE AND HISTORY. 5 vols. Macmillan, 1996; reprinted by permission of Gale Group.

- "Mary Hinkson in New Ballet Role", Philadelphia Tribune; accessed July 5, 2013.

- "Mary Hinkson Leaves City Opera Company", Philadelphia Tribune; accessed July 5, 2013.

- Tracy, Robert, Goddess: Martha Graham's Dancers Remember. New York: Limelight Editions (1997).

- 1925 births

- 2014 deaths

- American female dancers

- African-American female dancers

- Artists from Philadelphia

- Deaths from pulmonary fibrosis

- Disease-related deaths in New York (state)