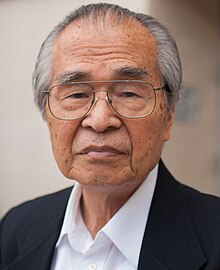

Masatoshi Nei

This biography of a living person relies too much on references to primary sources. (December 2019) |

Masatoshi Nei | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | January 2, 1931 Miyazaki Prefecture, Japan |

| Nationality | |

| Alma mater | |

| Known for | Statistical theories of molecular evolution and development of the theory of mutation-driven evolution |

| Awards | Kyoto Prize (2013) Thomas Hunt Morgan Medal (2006) International Prize for Biology (2002) |

| Scientific career | |

| Institutions | |

| Thesis | Studies on the Application of Biometrical Genetics to Plant Breeding (1959) |

| Website | igem |

Masatoshi Nei (根井正利, Nei Masatoshi) (born January 2, 1931) is a Japanese-born American evolutionary biologist currently affiliated with the Department of Biology at Temple University as a Carnell Professor. He was, until recently, Evan Pugh Professor of Biology at Pennsylvania State University and Director of the Institute of Molecular Evolutionary Genetics; he was there from 1990 to 2015.

Nei was born in 1931 in Miyazaki Prefecture, on Kyūshū Island, Japan. He was associate professor and professor of biology at Brown University from 1969 to 1972 and professor of population genetics at the Center for Demographic and Population Genetics, University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston (UTHealth), from 1972 to 1990. Acting alone or working with his students, he has continuously developed statistical theories of molecular evolution taking into account discoveries in molecular biology. He has also developed concepts in evolutionary theory and advanced the theory of mutation-driven evolution.

Together with Walter Fitch, Nei co-founded the journal Molecular Biology and Evolution in 1983 and the Society for Molecular Biology and Evolution in 1993.[1]

Work in population genetics[]

Theoretical studies[]

Nei was the first to show mathematically that, in the presence of gene interaction, natural selection always tends to enhance the linkage intensity between genetic loci or maintain the same linkage relationship.[2] He then observed that the average recombination value per genome is generally lower in higher organisms than in lower organisms and attributed this observation to his theory of linkage modification.[3] Recent molecular data indicate that many sets of interacting genes such as Hox genes, immunoglobulin genes, and histone genes have often existed as gene clusters for a long evolutionary time. This observation can also be explained by his theory of linkage modification. He also showed that, unlike R. A. Fisher's argument, deleterious mutations can accumulate rather quickly on the Y chromosome or duplicate genes in finite populations.[4][5]

In 1969, considering the rates of amino acid substitution, gene duplication, and gene inactivation, he predicted that higher organisms contain a large number of duplicate genes and nonfunctional genes (now called pseudogenes).[6] This prediction was shown to be correct when many multigene families and pseudogenes were discovered in the 1980s and 1990s.

His notable contribution in the early 1970s is the proposal of a new measure of genetic distance (Nei's distance) between populations and its use for studying evolutionary relationships of populations or closely related species.[7] He later developed another distance measure called DA, which is appropriate for finding the topology of a phylogenetic tree of populations.[8] He also developed statistics of measuring the extent of population differentiation for any types of mating system using the GST measure.[9] In 1975, he and collaborators presented a mathematical formulation of population bottleneck effects and clarified the genetic meaning of bottleneck effects.[10] In 1979, he proposed a statistical measure called nucleotide diversity,[11] which is now widely used for measuring the extent of nucleotide polymorphism. He also developed several different models of speciation and concluded that the reproductive isolation between species occurs as a passive process of accumulation of interspecific incompatibility mutations [12][13]

Protein polymorphism and neutral theory[]

In the early 1960s and 1970s, there was a great controversy over the mechanism of protein evolution and the maintenance of protein polymorphism. Nei and his collaborators developed various statistical methods for testing the neutral theory of molecular evolution using polymorphism data. Their analysis of the allele frequency distribution, the relationship between average heterozygosity and protein divergence between species, etc., showed that a large portion of protein polymorphism can be explained by neutral theory.[14][15] The only exception was the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) loci, which show an extraordinarily high degree of polymorphism. For these reasons, he accepted the neutral theory of evolution.[15][16]

Human evolution[]

Using his genetic distance theory, he and A. K. Roychoudhury showed that the genetic variation between Europeans, Asians, and Africans is only about 11 percent of the total genetic variation of the human population. They then estimated that Europeans and Asians diverged about 55,000 years ago and these two populations diverged from Africans about 115,000 years ago.[17][18] This conclusion was supported by many later studies using larger numbers of genes and populations, and the estimates appear to be still roughly correct. This finding represents the first indication of the out-of-Africa theory of human origins.[citation needed]

Molecular phylogenetics[]

Around 1980, Nei and his students initiated a study of inference of phylogenetic trees based on distance data. In 1985, they developed a statistical method for testing the accuracy of a phylogenetic tree by examining the statistical significance of interior branch lengths. They then developed the neighbor joining and minimum-evolution methods of tree inference.[19][20] They also developed statistical methods for estimating evolutionary times from molecular phylogenies. In collaboration with Sudhir Kumar and Koichiro Tamura, he developed a widely used computer program package for phylogenetic analysis called MEGA.[21]

MHC loci and positive Darwinian selection[]

Nei's group invented a simple statistical method for detecting positive Darwinian selection by comparing the numbers of synonymous nucleotide substitutions and nonsynonymous nucleotide substitutions.[22] Applying this method, they showed that the exceptionally high degree of sequence polymorphism at MHC loci is caused by overdominant selection.[23] Although various statistical methods for this test have been developed later, their original methods are still widely used.[24]

New evolutionary concepts[]

Nei and his students studied the evolutionary patterns of a large number of multigene families and showed that they generally evolve following the model of a birth–death process.[25] In some gene families, this process is very fast, caused by random events of gene duplication and gene deletion and generates genomic drift of gene copy number. Nei has long maintained the view that the driving force of evolution is mutation, including any types of DNA changes (nucleotide changes, chromosomal changes, and genome duplication), and that natural selection is merely a force eliminating less fit genotypes (i.e., theory of mutation-driven evolution).[15][24] He conducted statistical analyses of evolution of genes controlling phenotypic characters such as immunity and olfactory reception and obtained evidence supporting this theory.[24]

Select awards and honors[]

- 2013: Kyoto Prize in Basic Sciences[26]

- 2006: Thomas Hunt Morgan Medal

- 2002: Honorary Doctorate, University of Miyazaki

- 2002: International Prize for Biology, Japan Society for the Promotion of Science

- 1997: Member, National Academy of Sciences

Books[]

- Nei, M.(2013) Mutation-Driven Evolution. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Nei, M., and S. Kumar (2000) Molecular Evolution and Phylogenetics. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- National Research Council, (1996) The Evaluation of DNA Forensic Evidence. National Academies Press, Washington D.C.

- Roychoudhury, A. K., and M. Nei (1988) Human Polymorphic Genes: World Distribution. Oxford University Press, Oxford and New York.

- Nei, M. (1987) Molecular Evolutionary Genetics. Columbia University Press, New York.

- Nei, M., and R. K. Koehn (eds). (1983) Evolution of Genes and Proteins. Sinauer Assoc., Sunderland, MA.

- Nei, M. (1975) Molecular Population Genetics and Evolution. North-Holland, Amsterdam and New York.

References[]

- ^ Nei, Masatoshi (2014-06-01). "My memory of Walter Fitch (1929-2011) and starting molecular biology and evolution". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 31 (6): 1329–1332. doi:10.1093/molbev/msu133. PMC 4032136. PMID 24723418.

- ^ Nei, Masatoshi (1967). "Modification of linkage intensity by natural selection". Genetics. 57 (3): 625–641. doi:10.1093/genetics/57.3.625. PMC 1211753. PMID 5583732.

- ^ Nei, Masatoshi (1968). "Evolutionary change of linkage intensity". Nature. 218 (5147): 1160–1161. Bibcode:1968Natur.218.1160N. doi:10.1038/2181160a0. PMID 5656638. S2CID 4166761.

- ^ Nei, M (1970). "Accumulation of nonfunctional genes on sheltered chromosomes". Am. Nat. 104 (938): 311–322. doi:10.1086/282665. S2CID 85138712.

- ^ Nei, M.; Roychoudhury, A. K. (1973). "Probability of fixation of nonfunctional genes at duplicate loci". Am. Nat. 107 (955): 362–372. doi:10.1086/282840. S2CID 84684761.

- ^ Nei, M (1969). "Gene duplication and nucleotide substitution in evolution". Nature. 221 (5175): 40–42. Bibcode:1969Natur.221...40N. doi:10.1038/221040a0. PMID 5782607. S2CID 4180639.

- ^ Nei, M (1972). "Genetic distance between populations". Am. Nat. 106 (949): 283–292. doi:10.1086/282771. S2CID 55212907.

- ^ Nei, M.; Tajima, F.; Tateno, Y. (1983). "Accuracy of estimated phylogenetic trees from molecular data. II. Gene frequency data". J. Mol. Evol. 19 (2): 153–170. doi:10.1007/bf02300753. PMID 6571220. S2CID 19567426.

- ^ Nei, M (1973). "Analysis of gene diversity in subdivided populations". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 70 (12): 3321–3323. Bibcode:1973PNAS...70.3321N. doi:10.1073/pnas.70.12.3321. PMC 427228. PMID 4519626.

- ^ Nei, M.; Maruyama, T.; Chakraborty, R. (1975). "The bottleneck effect and genetic variability in populations". Evolution. 29: 1–10. doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.1975.tb00807.x. PMID 28563291.

- ^ Nei, Masatoshi; Li, Wen-Hsiung (1979). "Mathematical model for studying genetic variation in terms of restriction endonucleases". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 76 (10): 5269–5273. Bibcode:1979PNAS...76.5269N. doi:10.1073/pnas.76.10.5269. PMC 413122. PMID 291943.

- ^ Nei, M. T. Maruyama; Wu, C. I. (1983). "Models of evolution of reproductive isolation". Genetics. 103 (3): 557–579. doi:10.1093/genetics/103.3.557. PMC 1202040. PMID 6840540.

- ^ Nei, M.; Nozawa, M. (2011). "Roles of Mutation and Selection in Speciation: From Hugo de Vries to the modern genomic era". Genome Biol Evol. 3: 812–829. doi:10.1093/gbe/evr028. PMC 3227404. PMID 21903731.

- ^ Nei, M. (1983) Genetic polymorphism and the role of mutation in evolution (M. Nei and P. K. Koehn, eds.) Evolution of Genes and Proteins. Sinauer Assoc., Sunderland, MA, pp. 165-190.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Nei, M. (1987) Molecular Evolutionary Genetics. Columbia University Press, New York.

- ^ Li, W. H.; Gojobori, T.; Nei, M. (1981). "Pseudogenes as a paradigm of neutral evolution". Nature. 292 (5820): 237–239. Bibcode:1981Natur.292..237L. doi:10.1038/292237a0. PMID 7254315. S2CID 23519275.

- ^ Nei, M.; Roychoudhury, A. K. (1974). "Genic variation within and between the three major races of man, Caucasoids, Negroids, and Mongoloids". Am. J. Hum. Genet. 26 (4): 421–443. PMC 1762596. PMID 4841634.

- ^ Nei, M.; Roychoudhury, A. K. (1982). "Genetic relationship and evolution of human races". Evol. Biol. 14: 1–59.

- ^ Saitou, N.; Nei, M. (1987). "The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees". Mol. Biol. Evol. 4 (4): 406–425. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. PMID 3447015.

- ^ Rzhetsky, A.; Nei, M. (1993). "Theoretical foundation of the minimum-evolution method of phylogenetic inference". Mol. Biol. Evol. 10 (5): 1073–1095. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040056. PMID 8412650.

- ^ Kumar, S., K. Tamura, and M. Nei (1993) MEGA: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis. Ver. 1.02, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA.

- ^ Nei, M.; Gojobori, T. (1986). "Simple methods for estimating the numbers of synonymous and nonsynonymous nucleotide substitutions". Mol. Biol. Evol. 3 (5): 418–426. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040410. PMID 3444411.

- ^ Hughes, A. L.; Nei, M. (1988). "Pattern of nucleotide substitution at major histocompatibility complex class I loci reveals overdominant selection". Nature. 335 (6186): 167–170. Bibcode:1988Natur.335..167H. doi:10.1038/335167a0. PMID 3412472. S2CID 4352981.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Nei, M. (2013) Mutation-Driven Evolution. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- ^ Nei, M. and A. P. Rooney (2005) Concerted and birth-and-death evolution of multigene families.

- ^ "2013 Kyoto Prize Laureates | Masatoshi Nei". Kyoto Prize. 2013.

External links[]

| Scholia has an author profile for Masatoshi Nei. |

- Japanese geneticists

- Japanese molecular biologists

- American geneticists

- Statistical geneticists

- Living people

- Pennsylvania State University faculty

- Brown University faculty

- University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston faculty

- 1931 births

- People from Miyazaki Prefecture

- Kyoto University alumni

- Kyoto laureates in Basic Sciences

- Members of the United States National Academy of Sciences

- Evolutionary biologists

- Mutationism

- Population geneticists

- Japanese emigrants to the United States

- American academics of Japanese descent

- Highly Cited Researchers

- Temple University faculty