Mass arrests after Kristallnacht

Approximately 30,000 Jews in Germany and Austria were deported within the region or the country after the Kristallnacht of 9/10 November 1938.[1][2] They were deported to the concentration camps Buchenwald, Dachau and Sachsenhausen by the NSDAP organizations and the police in the days after the pogrom. This put pressure on the deportees and their relatives in order to speed up the only seemingly voluntary emigration from their homeland and to "Aryanize" Jewish assets.[3] The vast majority of the detainees were released by the beginning of 1939. Around 500 Jews were murdered, committed suicide or died as a result of ill-treatment and refused medical treatment in the concentration camps.

According to contemporary witnesses, the perpetrators' designation as Aktionsjuden was common at least in the Buchenwald concentration camp.[4] Presumably the name was derived from Aktion Rath, as the pogrom was sometimes called.[5]

Commands[]

Joseph Goebbels wrote in his diary that Adolf Hitler himself had ordered the arrest of 25,000 to 30,000 Jews.[6] Late in the evening of 9 November 1938, Heinrich Müller announced the planned "actions against the Jews" to the "Stapo" offices. The arrest of 20,000 to 30,000 mainly wealthy Jews had to be prepared.[7] In the early morning hours of 10 November, Reinhard Heydrich forwarded an order by Heinrich Himmler to all state police headquarters and SD top sections. Soon in all districts as many healthy male Jews - "especially wealthy" and "not too old" - were to be arrested as could be accommodated in the existing detention rooms. Maltreatment was forbidden.[8]

Arrest[]

The arrest action started immediately on 10 November and was stopped on 16 November by an order from Heydrich. In addition to the Gestapo and the local police, even the SA, SS and the National Socialist Motor Corps became active.

Heydrich's exact instructions were hardly taken into account.[9] On 11 November, an express order was issued to immediately release women and children arrested during the action. On 16 November, the dismissal of sick persons and persons over the age of sixty was ordered.[10]

Most male Jews were arrested in their homes, but arrests were also made at work, in hotels, schools and train stations. While the deployment of police officers in large cities was mostly formally correct and without additional humiliation or maltreatment, elsewhere insults, kicks and blows were not uncommon. Some of those arrested were coerced into singing National Socialist songs and exhaustive physical exercises and led through the city in "raids". In most cases the Jews taken into "protective custody" were held captive for the first two to three days in police stations, prisons, gyms or schools and from there transferred to concentration camps.

The historian Wolfgang Benz recorded that up to 10,000 Jews remained in prisons or local collection points because the accommodation available in concentration camps was insufficient.[11] Reliable figures and comprehensive information on their release from prison or the duration of their imprisonment are not available and there is a research deficit.

Transfer to concentration camp[]

Most of the prisoners arrived in the three concentration camps of Dachau, Sachsenhausen and Buchenwald in the first two to three days after the pogrom night. Further transports from Vienna arrived on the 22 November. The "Aktionsjuden" from Berlin were driven by trucks to the camp gate of Sachsenhausen. Others were transported by bus, train or suburban railway and then on foot. For Dachau, 10,911 Jews were committed, Buchenwald 9,845 and for Sachsenhausen the figure is estimated at 6,000.[12] This means that the total number of prisoners in concentration camps had doubled in an instant.

In many cases, the detainees were subjected to the brutality of the escorts during transport. According to some reports, "almost all prisoners", when they arrived in Dachau as well as in Buchenwald, showed traces of injuries, some of them serious, that they had suffered during or after their arrest.[13] Other police officers accompanying them testified that they had behaved correctly or even shown compassion.[14]

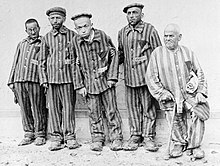

Camp stay[]

A humiliating admission procedure with hours of standing for roll calls, undressing, hair cutting and putting on the prisoners' clothes had a shocking effect on the victims and is widely described in eyewitness accounts. Bourgeois values and honorary titles suddenly no longer applied. This created feelings of degradation, lawlessness and being at the mercy of others.

The accommodation in Buchenwald was completely inadequate, where five windowless barracks were each occupied by 2000 "Aktionsjuden" and sanitary facilities were initially lacking. The daily routine was structured by three roll calls, which often lasted for hours and became a torture in rain and cold. Sometimes the detainees had to exercise and perform meaningless and physically demanding tasks. In Dachau, the number of registered deaths rose disproportionately.[15]

Parole[]

The duration of the imprisonment was very different. From the end of November 1938, 150 to 250 "Aktionsjuden" were released daily.[14] On 1 January 1939, 1,605 Jews were still imprisoned in Buchenwald and 958 in Sachsenhausen.

The reports of the "Aktionsjuden" show that they could not identify any system or criteria for the dismissals. On 28 November 1938, the release of young people under the age of sixteen was ordered, as was the release of front fighters. As of 12 December, the inmates over 50 years of age were to be released, and as of 21 December, Jewish teachers were to be given preferential dismissal.[16] Others gained their freedom because their plans to leave the country had already reached an advanced stage or even their visas were threatening to expire. Still others were released immediately after the transfer of their villa. Jewish car owners, who had their driving license revoked from 3 December 1938, were pressured to sell their cars at a ridiculous price. Anyone who refused to make such a request could nevertheless be unexpectedly dismissed.[17]

Repercussions[]

The number of "Aktionsjuden" who died in the concentration camp was at least 185 in Dachau, 233 in Buchenwald and 80 to 90 in Sachsenhausen. Reports cite physical overexertion, septic illnesses, pneumonia, lack of prescribed medication and diet as the main causes of death.[18] Many men suffered from the consequences of the prison conditions and became ill after release. In the Jüdisches Krankenhaus Berlin, about 600 emergency amputations had to be carried out, which were necessary due to untreated wounds and frostbite.[19]

Relatives noticed psychological changes in their returned men. Speechlessness, sleep disturbances, fear and shame were often the reaction to the sudden loss of bourgeois reputation, the raw assaults experienced and the experience of absolute powerlessness and lawlessness.

The halfway regulated emigration became a panic flight. Families were forced to separate in order to flee individually to a foreign country or at least to remove their children from Germany. At least 18,000 children were transported with Kindertransport to Great Britain, Belgium, Sweden, the Netherlands or Switzerland.[20]

References[]

- ^ Der Ort des Terrors : Geschichte der nationalsozialistischen Konzentrationslager. Benz, Wolfgang., Distel, Barbara. München: C.H. Beck. 2005. pp. 156, 161. ISBN 978-3-406-52960-3. OCLC 58602670.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Wünschmann, Kim. Before Auschwitz : Jewish prisoners in the prewar concentration camps. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. p. 168. ISBN 978-0-674-42556-9. OCLC 904398276.

- ^ Mitglieder der Häftlingsgesellschaft auf Zeit. "Die Aktionsjuden". Bader, Uwe. Dachau: Verl. Dachauer Hefte. 2005. p. 179. ISBN 3-9808587-6-6. OCLC 181469918.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Mitglieder der Häftlingsgesellschaft auf Zeit. "Die Aktionsjuden". Wolfgang Benz. Dachau: Verl. Dachauer Hefte. 2005. p. 187. ISBN 3-9808587-6-6. OCLC 181469918.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Der Ort des Terrors : Geschichte der nationalsozialistischen Konzentrationslager/ Masseneinweisungen in Konzentrationslager. Stefanie Schüler-Springorum. München: Benz, Wolfgang. 2005. p. 161. ISBN 3-406-52961-5. OCLC 58602670.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Heim, Susanne (2009). Die Verfolgung und Ermordung der europäischen Juden durch das nationalsozialistische Deutschland, 1933-1945. München: DE GRUYTER OLDENBOURG. p. 365. ISBN 978-3-486-58480-6. OCLC 209333149.

- ^ Der Nürnberger Prozess gegen die Hauptkriegsverbrecher... International Military Tribunal. München: Delphin-Verl. 1989. pp. 376–. ISBN 3-7735-2521-4. OCLC 830832921.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Der Nürnberger Prozess gegen die Hauptkriegsverbrecher vor dem Internationalen Militärgerichtshof ... International Military Tribunal. München: Delphin-Verl. 1989. p. 517. ISBN 3-7735-2524-9. OCLC 830832934.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Pollmeier, Heiko (1999). Jahrbuch für Antisemitismusforschung 8 /Inhaftierung und Lagererfahrung deutscher Juden im November 1938. Technische Universität Berlin. Berlin: Metropol. p. 108. ISBN 3-593-36200-7. OCLC 938783055.

- ^ Mitglieder der Häftlingsgesellschaft ... Dachau: Verl. Dachauer Hefte. 2005. p. 191. ISBN 3-9808587-6-6. OCLC 181469918.

- ^ Mitglieder der Häftlingsgesellschaft ... Dachau: Verl. Dachauer Hefte. 2005. p. 180. ISBN 3-9808587-6-6. OCLC 181469918.

- ^ Pollmeier, Heiko. Inhaftierung und Lagererfahrung... p. 111.

- ^ Distel, Barbara (1998). Die letzte ernste Warnung vor der Vernichtung. Zeitschrift f. Geschichtswissenschaft. p. 986.

- ^ a b Pollmeier, Heiko. Inhaftierung und Lagererfahrung …. p. 110.

- ^ Distel, Barbara (1998). Die letzte ernste Warnung vor der Vernichtung. Zeitschrift f. Geschichtswissenschaft. p. 987.

- ^ Benz, Wolfgang (2005). Mitglieder der Häftlingsgesellschaft auf Zeit. "Die Aktionsjuden". Dachau: Verl. Dachauer Hefte. p. 989. ISBN 3-9808587-6-6. OCLC 181469918.

- ^ Distel, Barbara (1998). Die letzte ernste Warnung vor der Vernichtung. Zeitschrift f. Geschichtswissenschaft. p. 989.

- ^ Heim, Susanne (2009). Die Verfolgung und Ermordung der europäischen Juden durch das nationalsozialistische Deutschland 1933-1945 Band 2. München: DE GRUYTER OLDENBOURG. p. 56. ISBN 978-3-486-58523-0.

- ^ Pollmeier, Heiko. Inhaftierung und Lagererfahrung …. p. 117.

- ^ Heim, Susanne (2009). Die Verfolgung und Ermordung der europäischen Juden durch das nationalsozialistische Deutschland 1933-1945 Band 2. München: DE GRUYTER OLDENBOURG. p. 45. ISBN 978-3-486-58523-0.

- Nazi terminology

- The Holocaust in Germany