Matchlock

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2008) |

The matchlock was the first mechanism invented to facilitate the firing of a hand-held firearm. Before this, firearms (like the hand cannon) had to be fired by applying a lit match (or equivalent) to the priming powder in the flash pan by hand; this had to be done carefully, taking most of the soldier's concentration at the moment of firing, or in some cases required a second soldier to fire the weapon while the first held the weapon steady. Adding a matchlock made the firing action simple and reliable by a single soldier, allowing them to keep both hands steadying the gun and eyes on the target while firing.

Description[]

The classic matchlock gun held a burning slow match in a clamp at the end of a small curved lever known as the serpentine. Upon the pull of a lever (or in later models a trigger) protruding from the bottom of the gun and connected to the serpentine, the clamp dropped down, lowering the smoldering match into the flash pan and igniting the priming powder. The flash from the primer traveled through the touch hole igniting the main charge of propellant in the gun barrel. On release of the lever or trigger, the spring-loaded serpentine would move in reverse to clear the pan. For obvious safety reasons, the match would be removed before reloading of the gun. Both ends of the match were usually kept alight in case one end should be accidentally extinguished.[1]

Earlier types had only an "S"-shaped serpentine pinned to the stock either behind or in front of the flash pan (the so-called "serpentine lock"), one end of which was manipulated to bring the match into the pan.[2][3]

Most matchlock mechanisms mounted the serpentine forward of the flash pan. The serpentine dipped backward, toward the firer, to ignite the priming. This is the reverse of the familiar forward-dipping hammer of the flintlock and later firearms.[citation needed]

A later addition to the gun was the rifled barrel. This made the gun much more accurate at longer distances but did have drawbacks, the main one being that it took much longer to reload because the bullet had to be pounded down into the barrel.[4]

A type of matchlock was developed called the snap matchlock,[5] in which the serpentine was held in firing position by a weak spring,[6] and released by pressing a button, pulling a trigger, or even pulling a short string passing into the mechanism. As the match was often extinguished after its relatively violent collision with the flash pan, this type fell out of favour with soldiers, but was often used in fine target weapons.

An inherent weakness of the matchlock was the necessity of keeping the match constantly lit. The match was steeped in potassium nitrate to keep the match lit for extended periods of time.[4] Being the sole source of ignition for the powder, if the match was not lit when the gun needed to be fired, the mechanism was useless, and the weapon became little more than an expensive club. This was chiefly a problem in wet weather, when damp match cord was difficult to light and to keep burning. Another drawback was the burning match itself. At night, the match would glow in the darkness, possibly revealing the carrier's position. The distinctive smell of burning match-cord was also a giveaway of a musketeer's position (this was used as a plot device by Akira Kurosawa in his movie Seven Samurai). It was also quite dangerous when soldiers were carelessly handling large quantities of gunpowder (for example, while refilling their powder horns) with lit matches present. This was one reason why soldiers in charge of transporting and guarding ammunition were amongst the first to be issued self-igniting guns like the wheellock and snaphance.

The matchlock was also uneconomical to keep ready for long periods of time. To maintain a single sentry on night guard duty with a matchlock, keeping both ends of his match lit, required a mile of match per year.[7]

History[]

The earliest form of matchlock in Europe appeared by 1411 and in the Ottoman Empire by 1425.[8] This early arquebus was a hand cannon with a serpentine lever to hold matches.[9] However this early arquebus did not have the matchlock mechanism traditionally associated with the weapon. The exact dating of the matchlock addition is disputed. The first references to the use of what may have been matchlock arquebuses (tüfek) by the Janissary corps of the Ottoman army date them from 1394 to 1465.[8] However it's unclear whether these were arquebuses or small cannons as late as 1444, but according to Gábor Ágoston the fact that they were listed separate from cannons in mid-15th century inventories suggest they were handheld firearms, though he admits this is disputable.[10] Godfrey Goodwin dates the first use of the matchlock arquebus by the Janissaries to no earlier than 1465.[11] The idea of a serpentine later appeared in an Austrian manuscript dated to the mid-15th century. The first dated illustration of a matchlock mechanism dates to 1475, and by the 16th century they were universally used. During this time the latest tactic in using the matchlock was to line up and send off a volley of musket balls at the enemy. This volley would be much more effective than single soldiers trying to hit individual targets.[4]

Robert Elgood theorizes the armies of the Italian states used the arquebus in the 15th century, but this may be a type of hand cannon, not matchlocks with trigger mechanism. He agreed that the matchlock first appeared in Western Europe during the 1470s in Germany.[12] Improved versions of the Ottoman arquebus were transported to India by Babur in 1526.[13]

A primitive long gun called Java arquebus was used by Majapahit Empire and the neighboring kingdoms in the last quarter of 15th century.[14] The weapon was very long, may have reached 2.2 m in length, and had its own folding bipod.[15]

The matchlock was claimed to have been introduced to China by the Portuguese. The Chinese obtained the matchlock arquebus technology from the Portuguese in the 16th century and matchlock firearms were used by the Chinese into the 19th century.[16] The Chinese used the term "bird-gun" to refer to muskets and Turkish muskets may have reached China before Portuguese ones.[17]

In Japan, the first documented introduction of the matchlock, which became known as the tanegashima, was through the Portuguese in 1543.[18] The tanegashima seems to have been based on snap matchlocks that were produced in Portuguese Malacca, at the armory of Malacca (a colony of Portugal since 1511), called an istinggar.[19] While the Japanese were technically able to produce tempered steel (e.g. sword blades), they preferred to use work-hardened brass springs in their matchlocks. The name tanegashima came from the island where a Chinese junk (a type of ship) with Portuguese adventurers on board was driven to anchor by a storm. The lord of the Japanese island Tanegashima Tokitaka (1528–1579) purchased two matchlock rifles from the Portuguese and put a swordsmith to work copying the matchlock barrel and firing mechanism. Within a few years, the use of the tanegashima in battle forever changed the way war was fought in Japan.[20]

Despite the appearance of more advanced ignition systems, such as that of the wheellock and the snaphance, the low cost of production, simplicity, and high availability of the matchlock kept it in use in European armies until about 1720. It was eventually completely replaced by the flintlock as the foot soldier's main armament.

In Japan, matchlocks continued to see military use up to the mid-19th century. In China, matchlock guns were still being used by imperial army soldiers in the middle decades of the 19th century.[21]

There is evidence that matchlock rifles may have been in use among some peoples in Christian Abyssinia in the late Middle Ages. Although modern rifles were imported into Ethiopia during the 19th century, contemporary British historians noted that, along with slingshots, matchlock rifle weapons were used by the elderly for self-defense and by the militaries of the Ras.[22][23]

Under Qing rule, the Hakka on Taiwan owned matchlock muskets. Han people traded and sold matchlock muskets to the Taiwanese aborigines. During the Sino-French War, the Hakka and Aboriginals used their matchlock muskets against the French in the Keelung Campaign and Battle of Tamsui. The Hakka used their matchlock muskets to resist the Japanese invasion of Taiwan (1895) and Han Taiwanese and Aboriginals conducted an insurgency against Japanese rule.

20th century use[]

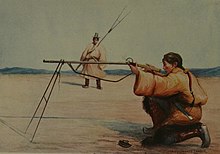

Tibetans have used matchlocks from as early as the sixteenth century until very recently.[24] The early 20th century explorer Sven Hedin also encountered Tibetan tribesmen on horseback armed with matchlock rifles along the Tibetan border with Xinjiang. Tibetan nomad fighters used arquebuses for warfare during the Chinese invasion of Tibet as late as the second half of the 20th century—and Tibetan nomads reportedly still use matchlock rifles to hunt wolves and other predatory animals.[25] These matchlock arquebuses typically feature a long, sharpened retractable forked stand.

Literary references[]

A Spanish matchlock, purchased in Holland, plays an important role in Walter D. Edmonds' Newbery Award-winning children's novel The Matchlock Gun.

References[]

- ^ Article on Encyclopaedia Britannica explaining the matchlock system

- ^ Ágoston, Gábor (2005). Guns for the Sultan. Cambridge University Press. p. 88. ISBN 978-0-521-84313-3.

- ^ "Handgonnes and Matchlocks". Retrieved 2008-12-05.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Weir, William (2005). 50 Weapons That Changed Warfare. Franklin Lakes, NJ: Career Press. pp. 71–74. ISBN 978-1-56414-756-1.

- ^ Richard J. Garrett (2010). The Defences of Macau: Forts, Ships and Weapons over 450 years. Hong Kong University Press. p. 176. ISBN 978-988-8028-49-8.

- ^ Blair, Claude (1962). European & American Arms, C. 1100-1850. B. T. Batsford.

- ^ Dale Taylor (1997), The Writer's Guide to Everyday Life in Colonial America, ISBN 0-89879-772-1, p. 159.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Needham 1986, p. 443.

- ^ Needham 1986, p. 425.

- ^ Ágoston, Gábor (2011). "Military Transformation in the Ottoman Empire and Russia, 1500–1800". Kritika: Explorations in Russian and Eurasian History. 12 (2): 281–319 [294]. doi:10.1353/kri.2011.0018.

Initially the Janissaries were equipped with bows, crossbows, and javelins. In the first half of the 15th century, they began to use matchlock arquebuses, although the first references to the Ottomans’ use of tüfek or hand firearms of the arquebus type (1394, 1402, 1421, 1430, 1440, 1442) are disputable.

- ^ Godfrey Goodwin: The Janissaries, saqu Books, 2006, p. 129 ISBN 978-0-86356-740-7

- ^ Elgood, Robert (1995). Firearms of the Islamic World: In the Tared Rajab Museum, Kuwait. I.B.Tauris. p. 41. ISBN 978-1-85043-963-9.

- ^ "Google Sites". sites.google.com.

- ^ Crawfurd, John (1856). A Descriptive Dictionary of the Indian Islands and Adjacent Countries. Bradbury and Evans.

- ^ Tiaoyuan, Li (1969). South Vietnamese Notes. Guangju Book Office.

- ^ Garrett, Richard J. (2010). The Defences of Macau: Forts, Ships and Weapons over 450 years. Hong Kong University Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-988-8028-49-8.

- ^ Kenneth Warren Chase (2003). Firearms: A Global History to 1700. Cambridge University Press. p. 144. ISBN 978-0-521-82274-9.

- ^ Lidin, Olof G. (2002). Tanegashima: The Arrival of Europe in Japan. NIAS Press. ISBN 978-87-91114-12-0.

- ^ The bewitched gun : the introduction of the firearm in the Far East by the Portuguese, by Rainer Daehnhardt 1994 P.26

- ^ Noel Perrin (1979). Giving up the gun: Japan's reversion to the sword, 1543–1879. David R Godine. ISBN 978-0-87923-773-8.

- ^ Jowett, Philip (2016). Imperial Chinese Armies 1840–1911. Osprey Publishing Ltd. p. 19.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh (1910). The Encyclopædia Britannica: A Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, Literature and General Information. At the University Press. p. 89.

- ^ Office, The Foreign (18 May 2018). "Memorandum on Abyssinia". The Journal of the Royal Geographical Society of London. 25: 215–218. doi:10.2307/1798118. JSTOR 1798118.

- ^ La Rocca, Donald J. "Tibetan Arms and Armor". www.metmuseum.org. Department of Arms and Armor, The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- ^ Goldstein, Melvyn (1990). Nomads of Western Tibet: The Survival of a Way of Life. ISBN 978-0520072114.

- Early firearms

- Firearm actions

- Muskets