Mauritania Railway

| Mauritania Railway | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

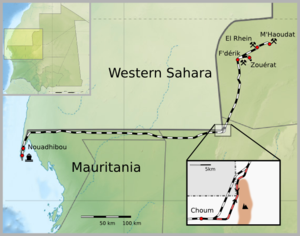

Map of Mauritania Railway | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Technical | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Line length | 704 km (437 mi) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Track gauge | 1,435 mm (4 ft 8+1⁄2 in) standard gauge | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Mauritania Railway is the national railway of Mauritania. Construction of the line began in 1960, with it opening in 1963.[1][2] It consists of a single, 704-kilometre (437 mi) railway line linking the iron mining centre of Zouerate with the port of Nouadhibou, via Fderik and Choum. The state agency Société Nationale Industrielle et Minière (National Mining and Industrial Company, SNIM) controls the railway line.

Since the closure of the Choum Tunnel, a 5 km (3.1 mi) section of the railway cuts through the Polisario Front-controlled part of the Western Sahara (21°21′18″N 13°00′46″W / 21.354867°N 13.012644°W).

History[]

The line was a success and provided a major portion of Mauritania's GDP; as a result the line was nationalised in 1974.[3] Following Mauritania's annexation of southern Western Sahara in 1976, the line came under constant attack by Polisario militia, effectively putting the line out of use and thereby crippling Mauritania's economy.[4] This played a major role in prompting the army to overthrow Mauritanian president Moktar Ould Daddah in 1978, followed by a withdrawal from Western Sahara the following year. With the line now secure, repairs were conducted and trains starting using it once again in the early 1980s.[5] This railway is unusual for its usage of the Soviet type coupler SA-3, which is quite rare in non ex-Soviet countries.[citation needed]

Traffic[]

Trains on the railway are up to 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) in length,[6] making them among the longest and heaviest in the world. They consist of 3 or 4 diesel-electric EMD locomotives, 200 to 210 cars each carrying up to 84 tons of iron ore, and 2-3 service cars. The total traffic averages 16.6 million tons per year.

Passengers are also occasionally transported by train; these services are managed by an SNIM subsidiary, the société d'Assainissement, de Travaux, de Transport et de Maintenance (abb. ATTM).[7] Passenger cars are sometimes attached to freight trains, but more often passengers simply ride atop the ore hopper cars freely. Passengers include locals, merchants, and rarely some tourists.[8] Conditions for these passengers are incredibly harsh with daytime temperatures exceeding 40°C and death from falls being common.[9]

In January 2019, the railway resumed tourism after a ten year hiatus; part of the track ran through a forbidden tourist area. One of the stops on the tourist route is an iron mine. The tourist route is typically operated by a locomotive carrying two passenger carriages. [10]

Locomotives[]

In October 2010, SNIM ordered six EMD SD-70ACS locomotives, with special modifications for operating in high temperatures.[11]

Glencore Xstrata[]

In 2014, the mining company Glencore paid $1 billion for 18 years of access to SNIM's rail and port infrastructure, which would be connected to branch lines to new iron mines at Askaf and . The deal would have saved the company the cost of constructing their own tracks and facilities.[12] However, Glencore backed out of the project just one year later after the price of iron ore tumbled nearly 40%.[13][14]

See also[]

- Economy of Mauritania

- History of rail transport in Mauritania

- Transport in Mauritania

- Railway stations in Mauritania

- Enclave and exclave - crossborder shortcut to avoid tunnel

References[]

Notes[]

- ^ "Mauritania, a Nation of Moorish Nomads, Suddenly Finds Herself in 20th Century". The New York Times. January 20, 1964.

last June, the 20th century elbowed its way into this Biblical picture

- ^ Pazzanita, Anthony G. (2008). Historical Dictionary of Mauritania. Scarecrow Press. pp. 424–25. ISBN 9780810862654. Retrieved 25 January 2020.

- ^ Pazzanita, Anthony G. (2008). Historical Dictionary of Mauritania. Scarecrow Press. pp. 424–25. ISBN 9780810862654. Retrieved 25 January 2020.

- ^ Pazzanita, Anthony G. (2008). Historical Dictionary of Mauritania. Scarecrow Press. pp. 424–25. ISBN 9780810862654. Retrieved 25 January 2020.

- ^ Pazzanita, Anthony G. (2008). Historical Dictionary of Mauritania. Scarecrow Press. pp. 424–25. ISBN 9780810862654. Retrieved 25 January 2020.

- ^ "The ore train". Société Nationale Industrielle et Minière. Archived from the original on September 19, 2008. Retrieved December 17, 2008.

- ^ http://www.attm.mr/index.php/entreprise/presentation

- ^ "The Best Train Journey in the World - Riding the Iron Ore Train, Mauritania". One Step 4Ward. 2016-02-29. Retrieved 2019-01-18.

- ^ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OiRD3GcjmKk&t=521s

- ^ "Desert train of Mauritania running again after 10 years". www.euronews.com. 18 January 2019. Retrieved 2019-01-18.

- ^ "Railway Gazette: High temperature locomotives ordered from EMD". Retrieved 2010-10-30.

- ^ http://www.railpage.com.au/f-t11332401.htm (registration required)

- ^ Ker, Peter (11 March 2015). "Glencore abandons Mauritania iron ore project after $US1bn investment". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 20 December 2018.

- ^ "Iron Ore Price Outlook". FocusEconomics. 13 February 2016. Retrieved 2019-08-26.

Further reading[]

- Robinson, Neil (2009). World Rail Atlas and Historical Summary. Volume 7: North, East and Central Africa. Barnsley, UK: World Rail Atlas Ltd. ISBN 978-954-92184-3-5.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mauritania Railway. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Mauritania#Get around. |

- SNIM train site

- Train images at Adventures in Mauritania

- Map of railway route

- This Sahara Railway Is One of the Most Extreme in the World (National Geographic's Short Film Showcase)

- Hot, free and dangerous: A train ride in Mauritania (Washington Post)

- The iron trains of Mauritania (Al Jazeera)

- Train to (almost) nowhere in Mauritania (New York Times)

- Atop a long train in Africa, heading for change (Reuters)

- The Mauritania Railway: Backbone of the Sahara, a short documentary film.

- Railway lines in Mauritania

- Railway companies of Mauritania

- Transport in Western Sahara

- Mauritania stubs

WikiMiniAtlas

WikiMiniAtlas