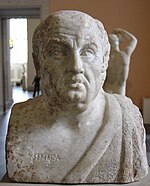

Medea (Seneca)

| Author | Lucius Annaeus Seneca |

|---|---|

| Country | Rome |

| Language | Latin |

| Genre | Tragedy |

| Set in | Corinth, Greece |

Publication date | 1st century |

| Text | Medea at Wikisource |

Medea is a fabula crepidata (Roman tragedy with Greek subject) of about 1027 lines of verse written by Seneca. It is generally considered to be the strongest of his earlier plays.[1] It was written around 50 CE. The play is about the vengeance of Medea against her betraying husband Jason and King Creon. The leading role, Medea, delivers over half of the play's lines.[2] Medea addresses many themes, one being that the title character represents "payment" for humans' transgression of natural laws.[3] She was sent by the gods to punish Jason for his sins. Another theme is her powerful voice that cannot be silenced, not even by King Creon.[3]

Characters[]

- Medea: daughter of King Aeëtes (King of Colchis), wife of Jason

- Chorus: Corinthians, hostile to Medea and not Jason

- Nutrix (nurse): nurse of Medea

- Creon: King of Corinth, father of Princess Creusa

- Jason: son of Aeson and husband of Medea who leaves her for the princess

- Nuntius (messenger)

- Two sons of Medea and Jason: mute characters

Background[]

Medea falls in love with Jason while he is on his quest for the Golden Fleece and uses her supernatural powers to aid him in completing the tasks that King Aeëtes, her father, had set.[4] The three tasks were: yoke the fiery bulls, compete with the giants, and slay the dragon that was guarding the fleece. After Jason is successful, Medea kills her own brother to distract her father and enable their escape.[5] After their return to Iolcus, they were again forced to flee when Medea uses her powers to have Jason's uncle Pelias killed by his own daughters. Jason and Medea next settle in Corinth where they had two sons.

Plot[]

In order to climb the political ladder, Jason (the leader of the Argonauts) leaves Medea for Creusa, the daughter of King Creon. Medea opens up the play by cursing Creusa and King Creon (1-44).[6] King Creon gives Medea one day before she is exiled and she does not take Jason's advice to leave peacefully (192-557).[6] Instead, she sends a poisoned robe as a gift for Creusa on her wedding day. The chorus describe the rage, scorn, and anger that Medea felt as she plotted her revenge. The chorus prays to the gods that Jason will be spared from Medea's vengeance (579-652).[6] Medea's curse contains poisons, snake blood, herbs, and the invocations to all the underworld gods. The cursed robe catches fire when Creusa puts it on. Creon tries to extinguish the fire but is unsuccessful, and he catches on fire as well (817-843).[6] Their death does not satisfy Medea but only awakens her vengeful spirit more. Jason's betrayal blinds Medea so much that she wishes to harm him even at the expense of her own children. Medea sacrifices her children from the roof of her house in order to hurt Jason (982-1025).[6] Medea escapes in a dragon chariot while she throws the bodies of the boys down. Jason closes the play by stating that there are no gods, because otherwise such acts would have not been committed (1026-1027).[6]

Euripides vs. Seneca[]

While Euripides' Medea shares similarities with Seneca’s version, they are also different in significant ways. Seneca's Medea was written after Euripides', and arguably his heroine shows a dramatic awareness of having to grow into her (traditional) role.[7] Seneca starts off his play with Medea herself expressing her hatred of Jason and Creon. Her first line is "O gods! Vengeance! Come to me now, I beg, and help me..."[6] while Euripides introduces Medea later on in scene one complaining to her nurse of the injustices she has faced. Where the chorus in Euripides' Medea shows sympathy towards her, the chorus in Seneca's Medea takes an objective position throughout the play, reflecting a Stoic morality.[8]

The final scenes are particularly different because Medea does not blame Jason for the death of her children in Seneca's version, even killing one of her sons in front of Jason and blaming herself for the death.[5] In Euripides' version Medea does the opposite, because she blames Jason and does not feel any guilt or blame for her actions.[citation needed]

Jason is made a more appealing figure by Seneca - thus strengthening the justification for, and power of, Medea’s passion.[9] Nevertheless the increased degree of stage violence in the Seneca,[10] and its extra gruesomeness, has led it to be seen as a coarser and more sensational version of Euripides’ play.[11]

Influence[]

The play contains lines which were seen during the European Age of Discovery as foretelling the discovery of the New World, and which were included in Christopher Columbus' Book of Prophecies:

- venient annis saecula seris,

- quibus Oceanus vincula rerum

- laxet et ingens pateat tellus

- Tethysque novos detegat orbes

- nec sit terris ultima Thule.[12][13]

References[]

- ^ Heil, Andreas; Damschen, Gregor (2013). Brill's Companion to Seneca: Philosopher and Dramatist. BRILL. p. 594. ISBN 978-9004217089. "Medea is often considered the masterpiece of Seneca's earlier plays, [...]"

- ^ A.D., Seneca, Lucius Annaeus, approximately 4 B.C.-65 (2014). Medea. Boyle, A. J. (Anthony James) (First ed.). Oxford. ISBN 9780199602087. OCLC 862091470.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Boyle, A.J. (1997). Tragic Seneca: An essay in the theatrical tradition. London and New York: Routledge. pp. 127.

- ^ Hine, H.M. (2000). ntroduction. Seneca. Medea, 6-49. With an introduction, text, translation and commentary. Warminster: Aris & Phillips. p. 22.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Lavilla de Lera, Jonathan (2016). "A metatheatrical perspective on the Medea of Seneca". Análisis. 47: 154.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g "SENECA THE YOUNGER, MEDEA - Theoi Classical Texts Library". www.theoi.com. Retrieved 2017-07-27.

- ^ L McClure, A Companion to Euripides (2017) p. 558.

- ^ M Nussbaum, The Therapy of Desire (Princeton 1994) p. 464

- ^ M Nussbaum, The Therapy of Desire (Princeton 1994) p. 464 and 445-6

- ^ L McClure, A Companion to Euripides (2017) p. 559

- ^ J Boardman ed. The Oxford History of the Classical World (Oxford 1986) p. 683-4

- ^ Diskin Clay, "Columbus' Senecan Prophecy," American Journal of Philology 113.4 (Winter, 1992) 617-620 https://www.jstor.org/stable/295543

- ^ Michael Gilleland, "The Discovery of the New World" https://laudatortemporisacti.blogspot.com/2016/10/the-discovery-of-new-world.html Oct 12, 2016

- Plays by Seneca the Younger

- Tragedy plays

- Works about Medea