Mental disorders and gender

| Part of a series on |

| Sex differences in humans |

|---|

| Physiology |

| Medicine |

| Neuroscience |

| Sociology |

Gender is correlated with the prevalence of certain mental disorders, including depression, anxiety and somatic complaints.[1] For example, women are more likely to be diagnosed with major depression, while men are more likely to be diagnosed with substance abuse and antisocial personality disorder.[1] There are no marked gender differences in the diagnosis rates of disorders like schizophrenia, borderline personality disorder, and bipolar disorder.[1][2] Men are at risk to suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) due to past violent experiences such as accidents, wars and witnessing death, and women are diagnosed with PTSD at higher rates due to experiences with sexual assault, rape and child sexual abuse.[3] Nonbinary or genderqueer identification describes people who do not identify as either male or female.[4] People who identify as nonbinary or gender queer show increased risk for depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder.[5] People who identify as transgender demonstrate increased risk for depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder. [6]

Sigmund Freud postulated that women were more prone to neurosis because they experienced aggression towards the self, which stemmed from developmental issues. Freud's postulation is countered by the idea that societal factors, such as gender roles, may play a major role in the development of mental illness. When considering gender and mental illness, one must look to both biology and social/cultural factors to explain areas in which men and women are more likely to develop different mental illnesses. A patriarchal society, gender roles, personal identity, social media, and exposure to other mental health risk factors have adverse effects on the psychological perceptions of both men and women.

Gender differences in mental health[]

Gender-specific risk factors[]

Gender-specific risk factors increase the likelihood of getting a particular mental disorder based on one's gender. Some gender-specific risk factors that disproportionately affect women are income inequality, low social ranking, unrelenting child care, gender-based violence, and socioeconomic disadvantages.[7]

Anxiety[]

Women are two to three times more likely to be diagnosed with General Anxiety Disorder (GAD) than men and have higher self-reported anxiety scores.[8] In the United States, women are two times more likely to be diagnosed with Panic Disorder (PD) than men. Women are also twice as likely to be affected by specific phobias. In addition, Social Anxiety Disorder (SAD) occurs among women and men at similar rates. Obsessive-compulsive Disorder (OCD) affects both women and men equally.[9]

Anxiety can occur with other mental illnesses.[9] Compared to men, women are more likely to have multiple psychiatric disorders in their lifetimes such as a combination of general anxiety disorder and major depression.[10] As a coping mechanism, 30% of men with anxiety use substances.[11] Women also have a higher chance of having an anxiety disorder earlier than men. Girls have an increased likelihood of having an anxiety disorder than boys. Anxiety during a girl's childhood and adolescence are significantly associated with later depressive episodes and later suicide attempts.[8]

In most cases, anxiety treatment is indifferent to sex. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is around 60-70% successful for both women and men.[11]

Depression[]

Regardless of one's age and country of origin, women are more likely to have depression than men.[12] Major depressive disorder, also known as unipolar depression or MDD, is twice as common in women.[12] Risk factors such as traumatic experiences, gender-based roles, and stress are connected to depression.[7] In the United States and European region, women are more likely to attempt suicide than men.[13] However, the suicide rate in the United States is four times higher for men than women.[14] Another population of women affected by depression is older women. Depression is one of the leading mental disorders of older adults, and women are the majority of older adults with depression.[7]

Although men may have similar diagnosing scores to women, the presence of a gender bias results in an increased diagnosis of depression in women than men.[7]

According to a World Health Organization report from 2016, the burden of depression falls disproportionately on girls and women.[15][16] Moreover, women report higher rates of violent victimization, which might contribute to the gender gaps in depression.[16]

Postpartum depression[]

Men and women experience postpartum depression. Maternal postpartum depression affects around 13% of women. The rates of female postpartum depression are higher in developing countries at around 20%.[17] Paternal postpartum depression (PPPD) affects 1 out of 10 men. It is associated with a decrease in testosterone and an increase in depressive symptoms. Maternal postpartum depression is a significant risk factor of paternal postpartum depression.[18]

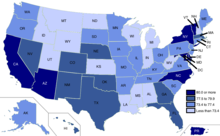

In the United States, 1 out of 7 women experiences postpartum depression.[19] In some American states, 1 out of 5 women is affected by postpartum depression.[20]

Eating disorders[]

Women constitute 85-95% of people with anorexia nervosa and bulimia and 65% of those with a binge-eating disorder.[21] Factors that contribute to the gender disproportionality of eating disorders are perceptions surrounding "thinness" in relation to success and sexual attractiveness and social pressures from mass media that are largely targeted towards women.[22] Between males and females, the symptoms experienced by those with eating disorders are very similar such as a distorted body image.[23]

Contrary to the stereotype of eating disorders' association with females, men also experience eating disorders. However, gender bias, stigma, and shame lead men to be underreported, underdiagnosed, and undertreated for eating disorders.[24] It has been found that clinicians are not well-trained and lack sufficient resources to treat men with eating disorders.[24] Men with eating disorders are likely to experience muscle dysmorphia.

Gender differences in adolescence and mental health[]

Adolescents experience mental illness differently than an adult, as children's brains are still developing and will continue to develop until around the age of twenty-five.[25] Children also approach goals differently, which in turn can cause different reactions to stressors such as bullying.[26]

Bullying[]

Studies have shown that adolescent males are more likely to be bullied than females. They have also posed that status enhancement is one of the main drives of bullying and a 1984 study by Kaj Björkqvist et al. showed that the motivation of male bullies between the ages of 14-16 was the status goal of establishing themselves as more dominant.[26]: 113 A bully's gender and the gender of their target can impact whether they are accepted or rejected by a gender group, as a 2010 study by René Veenstra et al. reported that bullies were more likely to be rejected by peer groups who saw them as a possible threat. The study cited an example of a male elementary school bully who was rejected by their female peers for targeting a female student while a male bully who only targeted other males were accepted by females but rejected by their male peers.[26]: 114

Eating disorders[]

The fashion industry and media have been cited as potential factors in the development of eating disorders in adolescents and pre-adolescents. Eating disorders have been found to be most common in developed countries and per scholars such as Anne Becker, the introduction of television has prompted an increase of eating disorders in media-naïve populations.[27]: 1304 [28] Females are more likely to have an eating disorder than males and scholars have stated that this has become more common "during the latter half of the twentieth century, during a period when icons of American beauty (Miss America contestants and Playboy centerfolds) have become thinner and women’s magazines have published significantly more articles on methods for weight loss".[29] Other potential reasons for eating disorders among adolescents and pre-adolescents can include anxiety,[30] food avoidance emotional disorder, food refusal, selective eating, pervasive refusal, or appetite loss as a result of depression.[28]

Suicide[]

Data has shown that suicide is the third leading cause of death in adolescents[31] and that gender has an impact on the avenue an adolescent may use when attempting suicide. Males are known more to use guns in their suicide attempts, whereas females are more likely to cut their wrists or take an overdose of pills.[32] Triggers for suicide among adolescents can include poor grades and relationship issues with significant others or family members.[32] Research has reported that while adolescents share common risk factors such as interpersonal violence, existing mental disorders and substance abuse, gender specific risk factors for suicide attempts can include eating disorders, dating violence, and interpersonal problems for females and disruptive behavior/conduct problems, homelessness, and access to means.[33] They also reported that females are more likely to attempt suicide than their male counterparts, whereas males are more likely to succeed in their attempts.[31]

Effects of Social Media on Body Image[]

During early adolescence, one's perception of physical appearance becomes increasingly important, having a significant impact on one's self-worth.[34] Studies have shown that social media use among adolescents is associated with poor body image.[35] This is due to the fact that social media use increases body surveillance. This means that adolescents regularly compare themselves to the idealized bodies they see on social media causing them to develop self-deprecating attitudes. Both adolescent boys and girls are impacted by the objectifying nature of social media, however young girls are more likely to body surveil due to society's tendency to overvalue and objectify women.[35] A study published in the Journal of Early Adolescence found that there is a significantly stronger correlation between self-objectified social media use, body surveillance, and body shame among young girls than young boys. The same studied emphasized that adolescence is an important psychological development period; therefore, opinions formed about oneself during this time can have a significant impact on self-confidence and self-worth.[35] Consequently, low self-esteem can increase one's risk of developing an eating disorder, depression, and/or anxiety. [35]

Gender differences following a traumatic event[]

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)[]

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is among the most common reactions in response to a traumatic event.[36] Research has found that women have higher rates of PTSD compared to men.[37] According to epidemiological studies, women are two to three times more likely to develop PTSD than men.[38] The lifetime prevalence of PTSD is about 10-12% in women and 5-6% in men.[38] Women are also four times more likely to develop chronic PTSD compared to men.[39] There are observed differences in the types of symptoms experienced by men and women.[38] Women are more likely to experience specific sub-clusters of symptoms, such as re-experiencing symptoms (e.g. flashbacks), hypervigilance, feeling depressed and numbness.[38][40] These differences are found to be persistent across cultures.[37] A significant risk factor or trigger of PTSD is rape. In the United States, 65% of men and 45.9% of women who are raped develop PTSD.[9]

Epidemiological studies have found that men are more likely to have PTSD as a result of experiencing combat, war, accidents, nonsexual assaults, natural disaster, and witnessing death or injury.[41] Meanwhile, women are more likely to have PTSD attributed to rape, sexual assault, sexual molestation, and childhood sexual abuse.[41][42] However, despite the theorized explanation that gender differences were due to different rates of exposure to high impact traumas such as sexual assaults, a meta-analysis found that when excluding instances of sexual assault or abuse, women remained at a greater risk for developing PTSD.[42] Additionally, it has been found that when looking at those who have only experienced sexual assaults, women remained approximately twice as likely as men to develop PTSD.[39] Thus, it is likely that exposure to specific traumatic events such as sexual assault only partially accounts for the observed gender differences in PTSD.[42]

Depression[]

While PTSD is perhaps the most well-known psychological response to a trauma, depression can also develop following exposure to traumatic events.[36] Under the definition of sexual assault as pressured or forced into unwanted sexual contact, women encounter two times the rate of sexual assault as men.[43] A history of sexual assault is related to increased rates of depression. For example, studies of survivors of childhood sexual assault found that the rates of childhood sexual assault ranged from 7-19% for women and 3-7% for men. This gender discrepancy in childhood sexual assault contributes to 35% of the gender difference in adult depression.[43] Increased likelihood of adverse traumatic experiences in childhood also explains the observed gender difference in major depression. Studies show that women have an increased risk of experiencing traumatic events in childhood, especially childhood sexual abuse.[44] This risk has been associated with an increased risk of developing depression.[44]

As with PTSD, evidence of a biological difference between men and women may contribute to the observed gender difference. However, research on the biological differences of men and women who have experienced traumatic events is yet to be conclusive.[43]

Gender differences in mental health within the LGBTQ+ community[]

Risk factors and the minority stress model[]

The minority stress model takes into account significant stressors that distinctly affect the mental health of those who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or another non-conforming gender identity.[45] Some risk factors that contribute to declining mental health are heteronormativity, discrimination, harassment, rejection (e.g., family rejection and social exclusion), stigma, prejudice, denial of civil and human rights, lack of access to mental health resources, lack of access to gender-affirming spaces (e.g., gender-appropriate facilities),[46] and internalized homophobia.[45][47] The structural circumstance where a non-heterosexual or gender non-conforming individual is embedded in significantly affects the potential sources of risk.[48] The compounding of these everyday stressors increase poor mental health outcomes among individuals in the LGBTQ+ community.[48] Evidence shows that there is a direct association between LGBTQ+ individuals' development of severe mental illnesses and the exposure to discrimination.[49]

In addition, there are a lack of access to mental health resources specific to LGBTQ+ individuals and a lack of awareness about mental health conditions within the LGBTQ+ community that restricts patients from seeking help.[47]

Limited research[]

There is limited research on mental health in the LGBTQ+ community. Several factors affect the lack of research on mental illness within non-heterosexual and non-conforming gender identities. Some factors identified: the history of psychiatry with conflating sexual and gender identities with psychiatric symptomatology; medical community's history of labelling gender identities such as homosexuality as an illness (now removed from the DSM); the presence of gender dysphoria in the DSM-V; prejudice and rejection from physicians and healthcare providers; LGBTQ+ underrepresentation in research populations; physicians' reluctance to ask patients about their gender; and the presence of laws against the LGBTQ+ community in many countries.[49][50] General patterns such as the prevalence of minority stress have been broadly studied.[45]

There is also a lack of empirical research on racial and ethnic differences in mental health status among the LGBTQ+ community and the intersection of multiple minority identities.[48]

Stigmatization of LGBTQ+ individuals with severe mental illnesses[]

There is a significantly greater stigmatization of LGBTQ+ individuals with more severe conditions. The presence of the stigma affects individuals' access to treatment and is particularly present for non-heterosexual and gender non-conforming individuals with schizophrenia.[49]

Anxiety[]

LGBTQ+ individuals are nearly three times more likely to experience anxiety compared to heterosexual individuals.[51] Gay and bisexual men are more likely to have generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) as compared to heterosexual men.[52]

Depression[]

Individuals who identify as non-heterosexual or gender non-conforming are more likely to experience depressive episodes and suicide attempts than those who identity as heterosexual.[49] Based solely on their gender identity and sexual orientation, LGBTQ+ individuals face stigma, societal bias, and rejection that increase the likelihood of depression.[47] Gay and bisexual men are more likely to have major depression and bipolar disorder than heterosexual men.[52]

Transgender youth are nearly four times more likely to experience depression, as compared to their non-transgender peers.[46] Compared to LGBTQ+ youth with highly accepting families, LGBTQ+ youth with less accepting families are more than three times likely to consider and attempt suicide.[46] As compared to individuals with a level of certainty in their gender identity and sexuality (such as LGB-identified and heterosexual students), youth who are questioning their sexuality report higher levels of depression and worse psychological responses to bullying and victimization.[48]

31% of LGBTQ+ older adults report depressive symptoms. LGBTQ+ older adults experience LGBTQ+ stigma and ageism that increase their likeliness to experience depression.[51]

Post-traumatic stress disorder[]

LGBTQ+ individuals experience higher rates of trauma than the general population, the most common of which include intimate partner violence, sexual assault and hate violence.[53] Compared to heterosexual populations, LGBTQ+ individuals are at 1.6 to 3.9 times greater risk of probable PTSD. One-third of PTSD disparities by sexual orientation are due to disparities in child abuse victimization.[54]

Suicide[]

As compared to heterosexual men, gay and bisexual men are at a greater risk for suicide, attempting suicide, and dying of suicide.[52] In the United States, 29% (almost one-third) of LGB youth have attempted suicide at least once.[55] Compared to heterosexual youth, LGB+ youth are twice as likely to feel suicidal and over four times as likely to attempt suicide.[46] Transgender individuals are at the greatest risk of suicide attempts.[51] One-third of transgender individuals (both in youth and adulthood) has seriously considered suicide and one-fifth of transgender youth has attempted suicide.[46][51]

LGBT+ youth are four times more likely to attempt suicide than heterosexual youth.[51] Youth who are questioning their gender identity and/or sexuality are two times more likely to attempt suicide than heterosexual youth.[51] Bisexual youth have higher percentages of suicidality than lesbian and gay youth.[48] As compared to white transgender individuals, transgender individuals who are African American/black, Hispanic/Latinx, American Indian/Alaska Native, or Multiracial are at a greater risk of suicide attempts.[51] 39% of LGBTQ+ older adults have considered suicide.[51]

Substance abuse[]

In the United States, an estimate of 20-30% of LGBTQ+ individuals abuse substances. This is higher than the 9% of the U.S. population that abuse substances. In addition, 25% of LGBTQ+ individuals abuse alcohol compared to the 5-10% of the general population.[47] Lesbian and bisexual youth have a higher percentage of substance use problems as compared to sexual minority males and heterosexual females.[48] However, as young sexual minority males mature into early adulthood, their rate of substance use increases.[48] Lesbian and bisexual women are twice as likely to engage in heavy alcohol drinking as compared to heterosexual women.[51] Gay and bisexual men are less likely to engage in heavy alcohol drinking as compared to heterosexual men.[51]

Substance use such as alcohol and drug use among LGBTQ+ individuals can be a coping mechanism in response to everyday stressors like violence, discrimination, and homophobia. Substance use can threaten LGBTQ+ individuals' financial stability, employment, and relationships.[52]

Eating disorders[]

The average age for developing an eating disorder is 19 years old for LGBTQ+ individuals, compared to 12–13 years old nationally.[56] In a national survey of LGBTQ youth conducted by the National Eating Disorders Association, The Trevor Project and the Reasons Eating Disorder Center in 2018, 54% of participants indicated that they had been diagnosed with an eating disorder.[57] An additional 21% of surveyed participants suspected that they had an eating disorder.[57]

Various risk factors may increase the likelihood of LGBTQ+ individuals experiencing disordered eating, including fear of rejection, internalized negativity, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or pressure to conform with body image ideals within the LGBTQ+ community.[58]

42% of men who experience disordered eating identify as gay.[58] Gay men are also seven times more likely to report binge eating and twelve times more likely to report purging than heterosexual men. Gay and bisexual men also experience a higher prevalence of full-syndrome bulimia and all subclinical eating disorders than their heterosexual counterparts.[58]

Research has found lesbian women to have higher rates of weight-based self-worth and proneness to contracting eating disorders compared to gay men.[59] Lesbian women also experience comparable rates of eating disorders compared to heterosexual women, with similar rates of dieting, binge eating and purging behaviours.[59] However, lesbian women are more likely to report positive body image compared to heterosexual females (42.1% vs 20.5%).[59]

Transgender individuals are significantly more likely than any other LGBTQ+ demographic to report an eating disorder diagnosis or compensatory behaviour related to eating.[60] Transgender individuals may use weight restriction to suppress secondary sex characteristics or to suppress or stress gendered features.[60]

There is limited research regarding racial differences within LGBTQ+ populations as it relates to disordered eating.[61] Conflicting studies have struggled to ascertain whether LGBTQ+ people of colour experience similar or varying rates of eating disorder proneness or diagnosis.[61]

Causes of gender disparities in mental disorders[]

Violence against women[]

There are different type of levels of violence that can occur against women. Violence was defined by World Health Organization as "the intentional use of physical force or power, threatened or actual, against oneself, another person, or against a group of community, which either results in has a high likelihood of resulting in injury, death, psychological harm, maldevelopment, or deprivation"[62]

Intimate partner violence/ domestic violence[]

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a particularly gendered issue. Data collected from the National Violence Against Women Survey (NVAWS) of women and men aged 18–65 found that women were significantly more likely than men to experience physical and sexual IPV.[36] According to The National Domestic Violence Hotline, "From 1994 to 2010, about 4 in 5 victims of intimate partner violence were female."[63]

There have been numerous studies conducted linking the experience of being a survivor of domestic violence to a number of mental health issues, including post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, depression, substance dependence, and suicidal attempts. Humphreys and Thiara (2003) assert that the body of existing research evidence shows a direct link between the experience of IPV and higher rates of self-harm, depression, and trauma symptoms.[37] The NVAWS survey found that physical IPV was associated with an increased risk of depressive symptoms, substance dependence problems, and chronic mental illness.[36]

A study conducted in 1995 of 171 women reporting a history of domestic violence and 175 reporting no history of domestic violence confirmed these hypotheses. The study found that the women with a history of domestic violence were 11.4 times more likely to suffer dissociation, 4.7 times more likely to suffer anxiety, 3 times as likely to suffer from depression, and 2.3 times more likely to have a substance abuse problem.[38] The same study noted that several of the women interviewed stated that they only began having mental health issues when they began to experience violence in their intimate relationships.[38]

In a similar study, 191 women who reported at least one event of IPV in their lifetime were tested for PTSD. 33% of the women tested positively were lifetime PTSD, and 11.4% tested positive for current PTSD.[64]

As far as males are concerned, it is estimated that 1 in 9 men experience severe IPV. For men as well, domestic violence is correlated with a higher risk of depression and suicidal behavior.[65]

Causes of intimate partner violence[]

One can identify several factors that are likely to lead to intimate partner violence:

- Intimate partner violence depends on socio-economic status (SES). The higher SES the less likely relationships will have financial difficulties. Financially stability can decrease IPV. Women who are not economically independent are less likely to escape a violent relationship since they might feel dependent and vulnerable. Additionally, lack of resources increases the levels of stress and conflict in the household.

- Food-insecurity at the household level is associated with increase experience of IPV.[66] vulnerable without them. Higher SES is associated with IPV.

- Domestic violence can also appear as a repetitive scheme. Indeed, men who witnessed their fathers using violence against their wife or children who experienced violence themselves are more likely to perpetrate inmate partner violence in their adult relationship.

- Poverty and substance may contribute to a violent behavior, since these substances diminish the control over one's violent impulsions.

- Lower levels of education

- a history of exposure to child maltreatment (perpetration and experience);

- Antisocial personality disorder

- Community norms that privilege or ascribe higher status to men and lower status to women;

- Low levels of women's access to paid employment.

How (IPV) impacts women's mental health[]

The United Nations estimates that "35 percent of women worldwide have experienced either physical and/or sexual intimate partner violence or sexual violence by a non-partner (not including sexual harassment) at some point in their lives."[67] Women's well-being are reported to be at risk due to Intimate partner violence. Indeed, evidence shows that women who have been confronted to IPV or sexual violence report higher rates of depression, psychosis, abortion and acquiring HIV, than women who have not. "Domestic violence is associated with depression, anxiety, PTSD and substance abuse in the general population. Additionally, women who are at risk can develop suicidal thoughts, depression, PTSD and anxiety."[68] The presence of domestic violence in their life causes psychiatric disorders amongst women survivors of domestic violence.

Another study found that in a group of women in a psychiatric inpatient hospital ward, women who were survivors of domestic violence were twice as likely to suffer depression as those were not.[37] All twenty of the women interviewed fit into a pattern of symptoms associated with trauma-based mental health disorders. Six of the women had attempted suicide. Moreover, the women spoke openly of a direct connection between the IPV they suffered and their resulting mental disorders.[37]

The direct psychological effects of IPV may contribute directly to the development of these disorders. In Humphreys' and Thiara's study, 60% of the women interviewed feared for their life, 69% feared for their emotional wellbeing, and 60% feared for their mental health. Some of the women discussed an undermining of their self-esteem, as well as an "overwhelming fear and erosion of their sense of safety."[37] Johnson and Ferraro (2000) refer to this overwhelming fear as "intimate terrorism," decimating a women's sense of security and contributing to a worsening psychological state.[69]

Humphreys and Thiara (2003) refer to these consequential mental disorders as "symptoms of abuse". That sentiment is echoed by some survivors who don't feel comfortable identifying with loaded diagnoses such as depression or PTSD.[37]

Sexual violence[]

The National Coalition against Domestic Violence provides useful guidelines to distinguish between sexual violence and domestic violence. Sexual violence describes a sexually abusive behavior by a partner or non-partner that can result in rape and sexual assault. Sometimes, in abusive relationships, sexual and domestic violence can intersect. "Between 14% and 25% of women are sexually assaulted by intimate partners during their relationship."[70]

Global estimates published by the World Health Organization indicate that about 1 in 3 (35%) of women worldwide have experienced either physical and/or sexual intimate partner violence or non-partner sexual violence in their lifetime.[71]

Sexual violence increasingly impact adolescent girls who are subjected to forced sex, rape and sexual assault. Approximately 15 million adolescent girls (aged 15 to 19) worldwide have experienced forced sex (forced sexual intercourse or other sexual acts) at some point in their life.

How sexual violence impacts women's mental health[]

Sexual assault, rape and sexual abuse are likely to impact a women's mental health on a short and long-term basis. Many survivors are "mentally marked by this trauma and report flashbacks of their assault, and feelings of shame, isolation, shock, confusion, and guilt."[72] Additionally, victims of rape or sexual assault are at a higher risk for developing depression, PTSD, Substance Use Disorders, Eating Disorders, Anxiety.

As an example, data suggests that 30 to 80 percent of sexual assault survivors develop PTSD.

Social Media Pressures and Criticism[]

Social media is highly prevalent and influential among the current generation of adolescents and young adults. Approximately 90% of young adults in the United States have and use a social media platform on a regular basis.[73] Social media has a substantial influence on how young adults perceive their physicality due to its appearance-focused nature. When individuals self-objectify by comparing themselves to others on social media, it can lead to increased body shame and body surveillance. In turn, these behaviors can results in an increased risk for disordered eating. The effect of social media use on self-objectification is greater in female users.[74] Women receive greater amounts of pressure and criticism surrounding their physical appearance, making them more likely to internalize the body ideals that are glorified on social media. Consequently, women face a higher risk of developing in body dissatisfaction or unhealthy eating behaviors.[75]

Gender bias in medicine[]

A gender bias exists in the very treatment of mental disorders. According to a study by the World Health Organization, "doctors are more likely to diagnose depression in women compared with men, even when they have similar scores on standardized measures of depression or present with identical symptoms".[76]

Alison Haggett argued in 2019 that there was less research devoted to mental health illness of men in Great Britain in the post-war era. She criticized that men's bad behavior is often labeled as toxic masculinity instead of examining the social and emotional reasons for that. As a result, "the mental health of men will remain poorly understood".[77]

Accordingly, gender stereotypes regarding the over-exposure of women to emotional problems and the higher risk of alcoholism among men, reinforce social stigma. Men and women willingly or unwillingly internalize these stereotypes. This internalization is then a barrier to accurate diagnosis and treatment of mental disorders. This phenomenon leads to a sort of self-fulfilling prophecy and traduces in patterns of help seeking for both men and women. Indeed, women are more likely to disclose mental health disorders to their physician while men are more likely to disclose problems with alcohol use.

The diagnosis of hysteria is a bright example of a medical diagnosis that was once almost exclusively applied to women. For hundred of years in Western Europe, hysteria was seen as an excess of emotion and a lack of self-control, that would mostly impact women. The diagnosis was used as a form of social labeling to discourage women from venturing outside of their role, that is a tool to take control over the increasing emancipation of women.

Implicit bias in medicine also affect the way lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender (LGBTQ+) patients, are diagnosed by mental health physicians. Due to internalized societal and medical bias, physicians are more likely to diagnosed LGBTQ+ patients with anxiety, depression and suicidality.[79]

Socioeconomic status (SES)[]

Socioeconomic Status is a global term which refers to a person's income level, education and position in society. Most social science research agrees upon the fact that there is a negative relationship between socioeconomic status and mental illness, that is lower socio-economic status is correlated with higher level of mental illness. "Researchers have found this relationship to hold constant for almost any mental illness, from rare conditions like schizophrenia to more common mental illnesses like depression."[80]

Gender disparities in socioeconomic status (SES)[]

SES is a key factor in determining one's opportunities and quality of life. Inequities in wealth and quality of life for women are known to exist both locally and globally. According to a 2015 survey of the U.S Census Bureau, in the United States, women's poverty rates are higher than men's. Indeed, "more than 1 in 7 women (nearly 18.4 million) lived in poverty in 2014."[81]

When it comes to income and earning ability in the United States, women are once again at an economic disadvantage. Indeed, for a same level of education and an equivalent field of occupation, men earn a higher wage than women. Though the pay-gap has narrowed over time, according U.S Census Bureau Survey, it was still 21% in 2014.[82] Additionally, pregnancy negatively affects professional and educational opportunities for women since "an unplanned pregnancies can prevent women from finishing their education or sustaining employment (Cawthorne, 2008)".[83]

The impact of gender disparities in SES on women's mental health[]

Increasing evidence tend to show a positive correlation between lower SES and negative mental health outcomes for women. Firstly, "Pregnant women with low SES report significantly more depressive symptoms, which suggests that the third trimester may be more stressful for low-income women (Goyal et al., 2010)."[81] Accordingly, postpartum depression has proven to be more prevalent among lower-income mothers. (Goyal et al., 2010).

Secondly, women are often the primary care-taker for their families. As a result, women with insecure job and housing experience higher stress and anxiety since their precarious economic situation places them and their children at higher risk of poverty and violent victimization (World Health Organization, 2013).

Finally, a low socioeconomic status puts women at higher risk of domestic and sexual violence, therefore increasing their exposure to all the mental disorder associated with this trauma. Indeed, "statistics show that poverty increases people's vulnerabilities to sexual exploitation in the workplace, schools, and in prostitution, sex trafficking, and the drug trade and that people with the lowest socioeconomic status are at greater risk for violence" (Jewkes, Sen, Garcia-Moreno, 2002).[84]

Biological differences[]

Research have been made on the effect of biological differences between male and female on the exposure to both Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and Depression.

Post-traumatic stress disorder[]

Biological differences is a proposed mechanism contributing to observed gender differences in PTSD. Dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis has been proposed for both men and women.[85] The HPA helps to regulate an individual's stress response by changing the amount of stress hormones released into the body, such as cortisol.[43] However, a meta-analysis found that women have greater dysregulation than men; women have been found to have lower circulating cortisol concentrations compared to healthy controls, where men did not have this difference in cortisol.[86] It is also thought that gender differences in threat appraisal might contribute to observed gender differences in PTSD as well by contributing to HPA dysregulation.[87] Women are reported to be more likely to appraise events as stressful and to report higher perceived distress in response to traumatic events compared to men, potentially leading to an increased dysregulation of the HPA in women than in men.[87] Recent research demonstrates a potential link between female hormones and the acquisition and extinction of fear responses. Studies suggest that higher levels of progesterone in women are associated with increased glucocorticoid availability, which may enhance consolidation and recall of distressful visual memories and intrusive thoughts. [88] One important challenge for future researchers is navigating fluctuations hormones throughout the menstrual cycle to further isolate the unique effects of estradiol and progesterone on PTSD.

Depression[]

Expanding on the research concerning the HPA and PTSD, one existing hypothesis is that women are more likely than men to have a dysregulated HPA in response to a traumatic event, like in PTSD. This dysregulation may occur as a result of the increased likelihood of women experiencing a traumatic event, as traumatic events have been known to contribute to HPA dysregulation.[43] Differences in stress hormone levels can influence moods due to the negative effect of high cortisol concentrations on biochemicals that regular mood such as serotonin.[43] Research has found that people with MDD have elevated cortisol levels in response to stress and that low serotonin levels are related to the development of depression.[43] Thus, it is possible that a dysregulation in the HPA, when combined with the increased history of traumatic events, may contribute to the gender differences seen in depression.[43]

Coping mechanisms in PTSD[]

For PTSD, genders differences in coping mechanisms has been proposed as a potential explanation for observed gender differences in PTSD prevalence rates.[38] Tough PTSD is a common diagnosis associated with abuse and trauma for men and women, the "most common mental health problem for women who are trauma survivors is depression".[89] Studies have found that women tend to respond differently to stressful situations than men. For example, men are more likely than women to react using the fight-or-flight response.[38] Additionally, men are more likely to use problem-focused coping,[38] which is known to decrease the risk of developing PTSD when a stressor is perceived to be within an individual's control.[90] Women, meanwhile, are thought to use emotion-focused, defensive, and palliative coping strategies.[38] As well, women are more likely to engage in strategies such as wishful thinking, mental disengagement, and the suppression of traumatic memories. These coping strategies have been found in research to correlate with an increased likelihood of developing PTSD.[39] Women are more likely to blame themselves following a traumatic event than men, which has been found to increase an individual's risk of PTSD.[39] In addition, women have been found to be more sensitive to a loss of social support following a traumatic event than men.[38] A variety of differences in coping mechanisms and use of coping mechanisms may likely play a role in observed gender differences in PTSD.

These described differences in coping mechanisms are in line with a preliminary model of sex-specific pathways to PTSD. The model, proposed by Christiansen and Elklit,[37] suggests that there are sex differences in the physiological stress response. In this model, variables such as dissociation, social support, and use of emotion-focused coping may be involved in the development and maintenance of PTSD in women, whereas physiological arousal, anxiety, avoidant coping, and use of problem-focused coping may be more likely to be related to the development and maintenance of PTSD in men.[37] However, this model is only preliminary and further research is needed.

For more about gender differences in coping mechanisms, see the Coping (psychology) page.

Coping mechanism among the LGBTQ+ community[]

Each individual has its own way to deal with difficult emotions and situations. Oftentimes, the coping mechanism adopted by a person, depending on whether they are safe or risky, will impact their mental health. These coping mechanisms tend to be developed during youth and early-adult life. Once a risky coping mechanism is adopted, it is often hard for the individual to get rid of it.

Safe coping-mechanisms, when it comes to mental disorders, involve communication with others, body and mental health caring, support and help seeking.[91]

Because of the high stigmatization they often experience in school, public spaces and society in general, the LGBTQ+ community, and more especially the young people among them are less likely to express themselves and seek for help and support, because of the lack of resources and safe spaces available for them to do so. As a result, LGBTQ+ patients are more likely to adopt risky coping mechanisms then the rest of the population.

These risky mechanisms involve strategies such as self-harm, substance abuse, or risky sexual behavior for many reasons, including; "attempting to get away from or not feel overwhelming emotions, gaining a sense of control, self-punishment, nonverbally communicating their struggles to others."[92] Once adopted, these coping mechanisms tend to stick to the person and therefore endanger even more the future mental health of LGBTQ+ patients, reinforcing their exposure to depression, extreme anxiety and suicide.

See also[]

- Gender bias in psychological diagnosis

- Gender differences in coping

- Gender dysphoria § Classification as a disorder

- Gender in individual mental disorders

- Healthcare and the LGBT community

- Minority stress

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Gender and women's health". World Health Organization. Retrieved 2007-05-13. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ Sansone, R. A.; Sansone, L. A. (2011). "Gender patterns in borderline personality disorder". Innovations in Clinical Neuroscience. 8 (5): 16–20. PMC 3115767. PMID 21686143.

- ^ "Why Women Have Higher Rates of PTSD Than Men". Psychology Today. Retrieved 2019-03-25.

- ^ Scandurra, Cristiano; Mezza, Fabrizio; Maldonato, Nelson Mauro; Bottone, Mario; Bochicchio, Vincenzo; Valerio, Paolo; Vitelli, Roberto (2019-06-25). "Health of Non-binary and Genderqueer People: A Systematic Review". Frontiers in Psychology. 10: 1453. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01453. ISSN 1664-1078. PMC 6603217. PMID 31293486.

- ^ Blueprint for the Provision of Comprehensive Care for Trans People and Trans Communities in Asia and the Pacific Archived 2019-04-16 at the Wayback Machine. Health Policy Project. Retrieved 2019-03-25.

- ^ Carmel, Tamar C.; Erickson-Schroth, Laura (2016-06-11). "Mental Health and the Transgender Population". Psychiatric Annals. 46 (6): 346–349. doi:10.3928/00485713-20160419-02. ISSN 0048-5713. PMID 28001287.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "WHO | Gender and women's mental health". WHO. Retrieved 2019-03-20.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Donner, Nina; Lowry, Christopher (May 2014). "Sex Differences in Anxiety and Emotional Behavior". Pflügers Archiv. 465 (5): 601–26. doi:10.1007/s00424-013-1271-7. PMC 3805826. PMID 23588380.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Facts & Statistics | Anxiety and Depression Association of America, ADAA". adaa.org. Retrieved 2019-03-21.

- ^ "Facts | Anxiety and Depression Association of America, ADAA". adaa.org. Retrieved 2019-03-21.

- ^ Jump up to: a b editor (2015-05-19). "Men and Anxiety". Anxiety Canada. Retrieved 2019-03-21.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- ^ Jump up to: a b Doering, Lynn V.; Eastwood, Jo-Ann (2011). "A Literature Review of Depression, Anxiety, and Cardiovascular Disease in Women". Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, & Neonatal Nursing. 40 (3): 348–361. doi:10.1111/j.1552-6909.2011.01236.x. ISSN 1552-6909. PMID 21477217.

- ^ WHO Regional Committee for Europe. "Fact Sheet -- Mental Health" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on January 7, 2018. Retrieved March 20, 2019.

- ^ "By the Numbers: Men and Depression". Monitor on Psychology. 46 (11): 13. December 2015. Retrieved March 20, 2019.

- ^ World Health Organization. Out of the shadows: Making mental health a global development priority. 2016 http://www.who.int/mental_health/advocacy/wb_background_paper.pdf?ua=1 Retrieved November 26, 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Salk, Rachel H.; Hyde, Janet S.; Abramson, Lyn Y. (2017). "Gender differences in depression in representative national samples: Meta-analyses of diagnoses and symptoms". Psychological Bulletin. 143 (8): 783–822. doi:10.1037/bul0000102. ISSN 1939-1455. PMC 5532074. PMID 28447828.

- ^ "WHO | Maternal mental health". WHO. Retrieved 2019-03-20.

- ^ "Oh Baby: Postpartum Depression in Men is Real, Science Says". PsyCom.net - Mental Health Treatment Resource Since 1986. Retrieved 2019-03-20.

- ^ American Psychological Association (2019). "Postpartum Depression". Retrieved March 20, 2019.

- ^ "Depression Among Women | Depression | Reproductive Health | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 2019-01-16. Retrieved 2019-03-20.

- ^ American Psychiatric Association (2017). "Mental Health Disparities: Women's Mental Health" (PDF). Retrieved March 22, 2019.

- ^ World Health Organization (2005). "Gender in Mental Health Research" (PDF). Retrieved March 22, 2019.

- ^ NIH Medline Plus. "Males and Eating Disorders". Retrieved March 25, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Strother, Eric; Lemberg, Raymond; Stanford, Stevie Chariese; Turberville, Dayton (October 2012). "Eating Disorders in men: Underdiagnosed, Undertreated, and Misunderstood". Eating Disorders. 20 (5): 346–355. doi:10.1080/10640266.2012.715512. PMC 3479631. PMID 22985232.

- ^ Lee, Francis S.; Heimer, Hakon; Giedd, Jay N.; Lein, Edward S.; Šestan, Nenad; Weinberger, Daniel R.; Casey, B.J. (31 October 2014). "Adolescent Mental Health—Opportunity and Obligation". Science. 346 (6209): 547–549. Bibcode:2014Sci...346..547L. doi:10.1126/science.1260497. PMC 5069680. PMID 25359951.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Salmivalli, Christina (March 2010). "Bullying and the peer group: A review". Aggression and Violent Behavior. 15 (2): 112–120. doi:10.1016/j.avb.2009.08.007.

- ^ Patel, Vikram; Flisher, Alan J; Hetrick, Sarah; McGorry, Patrick (April 2007). "Mental health of young people: a global public-health challenge". The Lancet. 369 (9569): 1302–1313. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60368-7. PMID 17434406. S2CID 34563002.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Becker, Anne E.; Burwell, Rebecca A.; Herzog, David B.; Hamburg, Paul; Gilman, Stephen E. (June 2002). "Eating behaviours and attitudes following prolonged exposure to television among ethnic Fijian adolescent girls". British Journal of Psychiatry. 180 (6): 509–514. doi:10.1192/bjp.180.6.509. ISSN 0007-1250. PMID 12042229.

- ^ Keel, Pamela K.; Klump, Kelly L. (2003). "Are eating disorders culture-bound syndromes? Implications for conceptualizing their etiology". Psychological Bulletin. 129 (5): 747–769. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.747. ISSN 1939-1455. PMID 12956542.

- ^ Thompson, J. Kevin. Smolak, Linda, 1951- (2001). Body image, eating disorders, and obesity in youth : assessment, prevention, and treatment. American Psychological Association. ISBN 1-55798-758-0. OCLC 45879641.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Jump up to: a b Santrock, John W. (September 2018). Essentials of life-span development (Sixth ed.). New York, NY. ISBN 978-1-260-05430-9. OCLC 1048028379.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Santrock, John W. (September 2018). Essentials of life-span development (Sixth ed.). New York, NY. ISBN 978-1-260-05430-9. OCLC 1048028379.

- ^ Miranda-Mendizabal, Andrea; Castellví, Pere; Parés-Badell, Oleguer; Alayo, Itxaso; Almenara, José; Alonso, Iciar; Blasco, Maria Jesús; Cebrià, Annabel; Gabilondo, Andrea; Gili, Margalida; Lagares, Carolina (March 2019). "Gender differences in suicidal behavior in adolescents and young adults: systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies". International Journal of Public Health. 64 (2): 265–283. doi:10.1007/s00038-018-1196-1. ISSN 1661-8556. PMC 6439147. PMID 30635683.

- ^ "Competence Considered. Edited by R. J. Sternberg and J. KolligianJr. (Pp. 420; £27.50.) Yale University Press: London. 1990". Psychological Medicine. 20 (4): 1006. November 1990. doi:10.1017/s0033291700037053. ISSN 0033-2917.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Fardouly, Jasmine; Vartanian, Lenny R. (June 2016). "Social Media and Body Image Concerns: Current Research and Future Directions". Current Opinion in Psychology. 9: 1–5. doi:10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.09.005.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Coker, Ann L; Davis, Keith E; Arias, Ileana; Desai, Sujata; Sanderson, Maureen; Brandt, Heather M; Smith, Paige H (1 November 2002). "Physical and mental health effects of intimate partner violence for men and women". American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 23 (4): 260–268. doi:10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00514-7. ISSN 0749-3797. PMID 12406480.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i Humphreys, Cathy; Thiara, Ravi (1 March 2003). "Mental Health and Domestic Violence: 'I Call it Symptoms of Abuse'". The British Journal of Social Work. 33 (2): 209–226. doi:10.1093/bjsw/33.2.209.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k Roberts, Gwenneth L.; Williams, Gail M.; Lawrence, Joan M.; Raphael, Beverley (1999-01-13). "How Does Domestic Violence Affect Women's Mental Health?". Women & Health. 28 (1): 117–129. doi:10.1300/J013v28n01_08. ISSN 0363-0242. PMID 10022060. S2CID 27088844.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d McLeer, Susan V; Anwar, A.H. Rebecca; Herman, Suzanne; Maquiling, Kevin (1989-06-01). "Education is not enough: A systems failure in protecting battered women". Annals of Emergency Medicine. 18 (6): 651–653. doi:10.1016/s0196-0644(89)80521-9. ISSN 0196-0644. PMID 2729689.

- ^ American Psychiatric Association (2017). "Mental Health Disparities: Women's Mental Health" (PDF). Retrieved March 22, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kessler, Ronald C. (1995-12-01). "Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey". Archives of General Psychiatry. 52 (12): 1048–60. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950240066012. ISSN 0003-990X. PMID 7492257. S2CID 14189766.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Tolin, David F.; Foa, Edna B. (2006). "Sex differences in trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder: A quantitative review of 25 years of research". Psychological Bulletin. 132 (6): 959–992. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.472.2298. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.132.6.959. ISSN 1939-1455. PMID 17073529.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h Nolen-Hoeksema, Susan (October 2001). "Gender Differences in Depression" (PDF). Current Directions in Psychological Science. 10 (5): 173–176. doi:10.1111/1467-8721.00142. hdl:2027.42/71710. ISSN 0963-7214. S2CID 1988591.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Piccinelli, Marco; Wilkinson, Greg (2000). "Gender differences in depression: Critical review". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 177 (6): 486–492. doi:10.1192/bjp.177.6.486. ISSN 0007-1250. PMID 11102321.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Dentato, Michael (April 2012). "The Minority Stress Perspective". American Psychological Association. Retrieved March 29, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Human Rights Campaign Foundation (July 2017). "The LGBTQ Community" (PDF). Retrieved April 1, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d National Alliance on Mental Illness. "LGBTQ". Retrieved March 30, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g Russell, Stephen; Fish, Jessica (2016). "Mental Health in Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) Youth". Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 12: 465–87. doi:10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-021815-093153. PMC 4887282. PMID 26772206.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Kidd, Sean; Howison, Meg; Pilling, Merrick; Ross, Lori; McKenzie, Kwame (February 29, 2016). "Severe Mental Illness among LGBT Populations: A Scoping Review". Psychiatric Services. 67 (7): 779–783. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.201500209. PMC 4936529. PMID 26927576.

- ^ The Shaw Mind Foundation (2016). "Mental Health in the LGBT Community" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on April 3, 2019. Retrieved March 29, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j American Psychiatric Association (2017). "Mental Health Disparities: LGBTQ" (PDF). Retrieved April 1, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Mental Health for Gay and Bisexual Men | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 2019-01-16. Retrieved 2019-04-02.

- ^ Ellis, Amy. "Web-Based Trauma Psychology Resources On Underserved Health Priority Populations for Public and Professional Education". American Psychological Association, Trauma Psychology Division.

- ^ Roberts, Andrea L.; Rosario, Margaret; Corliss, Heather L.; Koenen, Karestan C.; Austin, S. Bryn (2012). "Elevated Risk of Posttraumatic Stress in Sexual Minority Youths: Mediation by Childhood Abuse and Gender Nonconformity". American Journal of Public Health. 102 (8): 1587–1593. doi:10.2105/ajph.2011.300530. ISSN 0090-0036. PMC 3395766. PMID 22698034.

- ^ "LGBT Youth | Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Health | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 2018-11-19. Retrieved 2019-04-02.

- ^ "Eating Disorder Discrimination in the LGBT Community". Center For Discovery. 2018-01-30. Retrieved 2019-11-13.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Eating Disorders Among LGBTQ Youth: A 2018 National Assessment" (PDF). National Eating Disorder Association. The Trevor Project. 2018.CS1 maint: others (link)

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Eating Disorders in LGBTQ+ Populations". National Eating Disorders Association. 2017-02-25. Retrieved 2019-11-13.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c French, Simone A.; Story, Mary; Remafedi, Gary; Resnick, Michael D.; Blum, Robert W. (1996). "Sexual orientation and prevalence of body dissatisfaction and eating disordered behaviors: A population-based study of adolescents". International Journal of Eating Disorders. 19 (2): 119–126. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-108X(199603)19:2<119::AID-EAT2>3.0.CO;2-Q. ISSN 1098-108X. PMID 8932550.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Diemer, Elizabeth W.; Grant, Julia D.; Munn-Chernoff, Melissa A.; Patterson, David A.; Duncan, Alexis E. (2015). "Gender Identity, Sexual Orientation, and Eating-Related Pathology in a National Sample of College Students". Journal of Adolescent Health. 57 (2): 144–149. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.03.003. PMC 4545276. PMID 25937471.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Feldman, Matthew B.; Meyer, Ilan H. (2007). "Eating disorders in diverse lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations". International Journal of Eating Disorders. 40 (3): 218–226. doi:10.1002/eat.20360. PMC 2080655. PMID 17262818.

- ^ Han Almis, Behice; Koyuncu Kutuk, Emel; Gumustas, Funda; Celik, Mustafa (2018). "Risk Factors for Domestic Violence in Women and Predictors of Development of Mental Disorders in These Women". Nöropsikiyatri Arşivi. 55 (1): 67–72. doi:10.29399/npa.19355. ISSN 1309-4866. PMC 6045806. PMID 30042644.

- ^ "Statistics". The National Domestic Violence Hotline. Retrieved 2019-03-25.

- ^ Roberts, Gwenneth L.; Lawrence, Joan M.; Williams, Gail M.; Raphael, Beverley (1998-12-01). "The impact of domestic violence on women's mental health". Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health. 22 (7): 796–801. doi:10.1111/j.1467-842X.1998.tb01496.x. ISSN 1753-6405. PMID 9889446. S2CID 752614.

- ^ "NCADV | National Coalition Against Domestic Violence". ncadv.org. Retrieved 2019-04-18.

- ^ Gibbs, Andrew; Jewkes, Rachel; Willan, Samantha; Washington, Laura (2018-10-03). "Associations between poverty, mental health and substance use, gender power, and intimate partner violence amongst young (18-30) women and men in urban informal settlements in South Africa: A cross-sectional study and structural equation model". PLOS ONE. 13 (10): e0204956. Bibcode:2018PLoSO..1304956G. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0204956. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 6169941. PMID 30281677.

- ^ "Facts and figures: Ending violence against women". UN Women. Retrieved 2019-03-07.

- ^ Trevillion, Kylee; Oram, Siân; Feder, Gene; Howard, Louise M. (2012-12-26). "Experiences of Domestic Violence and Mental Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". PLOS ONE. 7 (12): e51740. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...751740T. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0051740. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3530507. PMID 23300562.

- ^ Johnson, Michael P.; Ferraro, Kathleen J. (2000-11-01). "Research on Domestic Violence in the 1990s: Making Distinctions". Journal of Marriage and Family. 62 (4): 948–963. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2000.00948.x. ISSN 1741-3737. S2CID 12584806.

- ^ Bennice; J.A & Resick (2003). Marital rape: History, research, and practice. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 4. pp. 228–246.

- ^ "Violence against women". www.who.int. Retrieved 2019-03-07.

- ^ "Sexual Assault and Mental Health". Mental Health America. 2017-03-31. Retrieved 2019-03-07.

- ^ Multidisciplinary social networks research : second International Conference, MISNC 2015, Matsuyama, Japan, September 1-3, 2015. Proceedings. Wang, Leon,, Uesugi, Shiro,, Ting, I-Hsien,, Okuhara, Koji,, Wang, Kai. Heidelberg. 2015-08-24. ISBN 978-3-662-48319-0. OCLC 919495107.CS1 maint: others (link)

- ^ Rounsefell, Kim (2020). "Social media, body image and food choices in healthy young adults: A mixed methods systematic review". Nutrition & Dietetics. 77 (1): 19–40. doi:10.1111/1747-0080.12581. PMC 7384161. PMID 31583837.

- ^ Hoffman, S.J (2013). "Following celebrities' medical advice: meta-narrative analysis". BMJ. 347: f7151. doi:10.1136/bmj.f7151.

- ^ "WHO | Gender and women's mental health". WHO. Retrieved 2019-03-08.

- ^ Haggett, Ali (2019), Kritsotaki, Despo; Long, Vicky; Smith, Matthew (eds.), "Preventing MalemasculinitygenderMental Illness in Post-war BritainBritain", Preventing Mental Illness: Past, Present and Future, Mental Health in Historical Perspective, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 257–280, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-98699-9_12, ISBN 978-3-319-98699-9, PMID 30840425

- ^ Briggs, Laura (2000). "The Race of Hysteria: "Overcivilization" and the "Savage" in Late Nineteenth-Century Obstetrics and Gynecology". American Quarterly. 52 (2): 246–273. doi:10.1353/aq.2000.0013. ISSN 1080-6490. PMID 16858900. S2CID 8047730.

- ^ Hatzenbuehler, Mark L.; Pachankis, John E. (December 2016). "Stigma and Minority Stress as Social Determinants of Health Among Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Youth". Pediatric Clinics of North America. 63 (6): 985–997. doi:10.1016/j.pcl.2016.07.003. ISSN 0031-3955. PMID 27865340.

- ^ "Types Of Mental Illness |". Retrieved 2019-03-08.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Magai, Carol (1992). "Fact Sheet: RU 486". doi:10.1037/e403702005-011. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ Norris, J. Michael (2009). "National Streamflow Information Program: Implementation Status Report". Fact Sheet. doi:10.3133/fs20093020. ISSN 2327-6932.

- ^ "California Reducing Disparities Project". Fact Sheet. 2010. doi:10.1037/e574412010-001.

- ^ Jewkes, Rachel; Guedes, Alessandra; Garcia-Moreno, Claudia (2012). "Preventing Child Abuse and Neglect for the Prevention of Sexual Violence". doi:10.1037/e516542013-033. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ Donner, Nina C.; Lowry, Christopher A. (2013). "Sex differences in anxiety and emotional behavior". Pflügers Archiv : European Journal of Physiology. 465 (5): 601–626. doi:10.1007/s00424-013-1271-7. ISSN 0031-6768. PMC 3805826. PMID 23588380.

- ^ Meewisse, Marie-Louise; Reitsma, Johannes B.; Vries, Giel-Jan De; Gersons, Berthold P. R.; Olff, Miranda (2007). "Cortisol and post-traumatic stress disorder in adults: Systematic review and meta-analysis". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 191 (5): 387–392. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.106.024877. ISSN 0007-1250. PMID 17978317.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Olff, Miranda; Langeland, Willie; Draijer, Nel; Gersons, Berthold P. R. (2007). "Gender differences in posttraumatic stress disorder". Psychological Bulletin. 133 (2): 183–204. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.133.2.183. ISSN 1939-1455. PMID 17338596.

- ^ Garcia, Natalia M.; Walker, Rosemary S.; Zoellner, Lori A. (2018-12-01). "Estrogen, progesterone, and the menstrual cycle: A systematic review of fear learning, intrusive memories, and PTSD". Clinical Psychology Review. 66: 80–96. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2018.06.005. ISSN 0272-7358. PMID 29945741.

- ^ Covington, Stephanie S. (July 2007). "Women and the Criminal Justice System". Women's Health Issues. 17 (4): 180–182. doi:10.1016/j.whi.2007.05.004. ISSN 1049-3867. PMID 17602965.

- ^ Hundt, Natalie; Williams, Ann; Mendelson, Jenna; Nelson-Gray, Rosemery (1 April 2013). "Coping mediates relationships between reinforcement sensitivity and symptoms of psychopathology". Personality and Individual Differences. 54 (6): 726–731. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2012.11.028.

- ^ trwd (2017-01-24). "Mental illness is a coping mechanism". National Empowerment Center. Retrieved 2019-04-04.

- ^ "Be true and be you: A basic mental health guide for LGBTQ teens" (PDF). Networkofcare.org.

Further reading[]

- Rabinowitz, Sam V.; Cochran, Fredric E. (2000). Men and Depression: Clinical and empirical perspectives. San Diego: Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-177540-7.

External links[]

- "Study Finds Sex Differences in Mental Illness", American Psychological Association

- Gender and society

- Mental and behavioural disorders

- Women and psychology

- Sex differences in humans