Mental rotation

Mental rotation is the ability to rotate mental representations of two-dimensional and three-dimensional objects as it is related to the visual representation of such rotation within the human mind.[1] There is a relationship between areas of the brain associated with perception and mental rotation. There could also be a relationship between the cognitive rate of spatial processing, general intelligence and mental rotation.[2][3][4]

Mental rotation can be described as the brain moving objects in order to help understand what they are and where they belong. Mental rotation has been studied to try to figure out how the mind recognizes objects in their environment. Researchers generally call such objects stimuli. Mental rotation is one cognitive function for the person to figure out what the altered object is.

Mental rotation can be separated into the following cognitive stages:[2]

- Create a mental image of an object from all directions (imagining where it continues straight vs. turns).

- Rotate the object mentally until a comparison can be made (orientating the stimulus to other figure).

- Make the comparison.

- Decide if the objects are the same or not.

- Report the decision (reaction time is recorded when level pulled or button pushed).

Assessment[]

In a mental rotation test, the participant compares two 3D objects (or letters), often rotated in some axis, and states if they are the same image or if they are mirror images (enantiomorphs).[1] Commonly, the test will have pairs of images each rotated a specific number of degrees (e.g. 0°, 60°, 120° or 180°). A set number of pairs will be split between being the same image rotated, while others are mirrored. The researcher judges the participant on how accurately and rapidly they can distinguish between the mirrored and non-mirrored pairs.[5]

Notable research[]

Shepard and Metzler (1971)[]

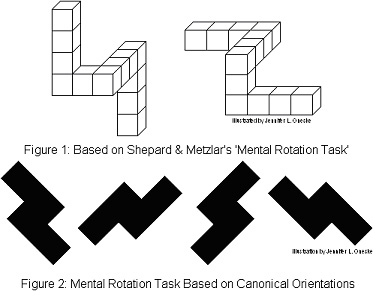

Roger Shepard and Jacqueline Metzler (1971) were some of the first to research the phenomenon.[6] Their experiment specifically tested mental rotation on three-dimensional objects. Each subject was presented with multiple pairs of three-dimensional, asymmetrical lined or cubed objects. The experiment was designed to measure how long it would take each subject to determine whether the pair of objects were indeed the same object or two different objects. Their research showed that the reaction time for participants to decide if the pair of items matched or not was linearly proportional to the angle of rotation from the original position. That is, the more an object has been rotated from the original, the longer it takes an individual to determine if the two images are of the same object or enantiomorphs.[7]

Vandenberg and Kuse (1978)[]

In 1978, Steven G. Vandenberg and Allan R. Kuse developed a test to assess mental rotation abilities that was based on Shepard and Metzler's (1971) original study. The Mental Rotations Test was constructed using India ink drawings. Each stimulus was a two-dimensional image of a three-dimensional object drawn by a computer. The image was then displayed on an oscilloscope. Each image was then shown at different orientations rotated around the vertical axis. Following the basic ideas of Shepard and Metzler's experiment, this study found a significant difference in the mental rotation scores between men and women, with men performing better. Correlations with other measures showed strong association with tests of spatial visualization and no association with verbal ability.[8][9]

Neural activity[]

In 1999, a study was conducted to find out which part of the brain is activated during mental rotation. Seven volunteers (four males and three females) between the ages of twenty-nine to sixty-six participated in this experiment. For the study, the subjects were shown eight characters 4 times each (twice in normal orientation and twice reversed) and the subjects had to decide if the character was in its normal configuration or if it was the mirror image. During this task, a PET scan was performed and revealed activation in the right posterior parietal lobe.[10]

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies of brain activation during mental rotation reveal consistent increased activation of the parietal lobe, specifically the inter-parietal sulcus, that is dependent on the difficulty of the task. In general, the larger the angle of rotation, the more brain activity associated with the task. This increased brain activation is accompanied by longer times to complete the rotation task and higher error rates. Researchers have argued that the increased brain activation, increased time, and increased error rates indicate that task difficulty is proportional to the angle of rotation.[11][12]

Color[]

Physical objects that people imagine rotating in everyday life have many properties, such as textures, shapes, and colors. A study at the University of California Santa Barbara was conducted to specifically test the extent to which visual information, such as color, is represented during mental rotation. This study used several methods such as reaction time studies, verbal protocol analysis, and eye tracking. In the initial reaction time experiments, those with poor rotational ability were affected by the colors of the image, whereas those with good rotational ability were not. Overall, those with poor ability were faster and more accurate identifying images that were consistently colored. The verbal protocol analysis showed that the subjects with low spatial ability mentioned color in their mental rotation tasks more often than participants with high spatial ability. One thing that can be shown through this experiment is that those with higher rotational ability will be less likely to represent color in their mental rotation. Poor rotators will be more likely to represent color in their mental rotation using piecemeal strategies (Khooshabeh & Hegarty, 2008).

Effect on athleticism and artistic ability[]

Research on how athleticism and artistic ability affect mental rotation has also been done. Pietsch, S., & Jansen, P. (2012) showed that people who were athletes or musicians had faster reaction times than people who were not. They tested this by splitting people from the age of 18 and higher into three groups. Group 1 was students who were studying math, sports students and education students. It was found that through the mental rotation test students who were focused on sports did much better than those who were math or education majors. Also it was found that the male athletes in the experiment were faster than females, but male and female musicians showed no significant difference in reaction time.

Moreau, D., Clerc, et al. (2012) also investigated if athletes were more spatially aware than non-athletes. This experiment took undergraduate college students and tested them with the mental rotation test before any sport training, and then again afterward. The participants were trained in two different sports to see if this would help their spatial awareness. It was found that the participants did better on the mental rotation test after they had trained in the sports, than they did before the training. There are ways to train your spatial awareness. This experiment brought to the research that if people could find ways to train their mental rotation skills they could perform better in high context activities with greater ease.

A study investigated the effect of mental rotation on postural stability. Participants performed a MR (mental rotation) task involving either foot stimuli, hand stimuli, or non-body stimuli (a car) and then had to balance on one foot. The results suggested that MR tasks involving foot stimuli were more effective at improving balance than hand or car stimuli, even after 60 minutes.[13]

Researchers studied the difference in mental rotation ability between gymnasts, handball, and soccer players with both in-depth and in-plane rotations. Results suggested that athletes were better at performing mental rotation tasks that were more closely related to their sport of expertise.[14]

There is a correlation in mental rotation and motor ability in children, and this connection is especially strong in boys ages 7–8. Children were known for having very connected motor and cognitive processes, and the study showed that this overlap is influenced by motor ability.[15]

A mental rotation test (MRT) was carried out on gymnasts, orienteers, runners, and non athletes. Results showed that non athletes were greatly outperformed by gymnasts and orienteers, but not runners. Gymnasts (egocentric athletes) did not outperform orienteers (allocentric athletes).[16]

Sex[]

Some studies have shown that there is a difference between male and female in mental rotation tasks. In order to explain this difference, brain activation during a mental rotation task was studied. In 2012, a study[17] have been done on people that graduated in sciences or in liberal arts. Males and females were asked to execute a mental rotation task, and their brain activity was recorded with an fMRI. The researchers found a difference of brain activation: males present a stronger activity in the area of the brain used in a mental rotation task.

A study from 2008 suggested that differences may occur early during development. The experiment was done on 3- to 4-month-old infants using a 2D mental rotation task. They used a preference apparatus that consists of observing during how much time the infant is looking at the stimulus. They started by familiarizing the participants with the number "1" and its rotations. Then they showed them a picture of a "1" rotated and its mirror image. The study showed that males are more interested by the mirror image. Females are equally interested by the "1" rotated and its mirror image. According to the study, this may mean that males and females, at least when infants, process mental rotation differently.[18]

Another study from 2015 was focused on women and their abilities in a mental rotation task and in an emotion recognition task. In this experiment, they induced a feeling or a situation in which women feel more powerful or less powerful. They were able to conclude that women in a situation of power are better in a mental rotation task (but less performant in an emotion recognition task) than other women.[19]

Studying differences between male and female brains can have interesting applications. For example, it could help in the understanding of the autism spectrum disorders. One of the theories concerning autism is the EMB (extreme male brain). This theory considers that autist have an "extreme male brain". In a study[20] from 2015, researchers confirmed that there is a difference between male and female in mental rotation task (by studying people without autism): males are more successful. Then they highlighted the fact that autists do not have this "male performance" in a mental rotation task. They conclude their study by "autistic people do not have an extreme version of a male cognitive profile as proposed by the EMB theory".[20]

Some recent studies suggest that difference between Mental rotation cognition task are a consequence of procedure and artificiality of the stimuli. A 2017 study leveraged photographs and three-dimensional models, evaluating multiple different approaches and stimuli. Results show that changing the stimuli can eliminate any male advantages found from the Vandenberg and Kuse test (1978). [21]

Current research directions[]

There may be relationships between competent bodily movement and the speed with which individuals can perform mental rotation. Researchers found children who trained with mental rotation tasks had improved strategy skills after practicing.[22] Follow-ups studies will compare the differences in the brain among the attempts to discover effects on other tasks and the brain. People use many different strategies to complete tasks; psychologists will study participants who use specific cognitive skills to compare competency and reaction times.[23] Others will continue to examine the differences in competency of mental rotation based on the objects being rotated.[24] Participants' identification with the object could hinder or help their mental rotation abilities across gender and ages to support the earlier claim that males have faster reaction times.[17][25][26] Psychologists will continue to test similarities between mental rotation and physical rotation, examining the difference in reaction times and relevance to environmental implications.[27]

See also[]

Notes[]

- ^ a b Shepard, R. N.; Metzler, J. (19 February 1971). "Mental Rotation of Three-Dimensional Objects". Science. 171 (3972): 701–703. Bibcode:1971Sci...171..701S. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.610.4345. doi:10.1126/science.171.3972.701. PMID 5540314. S2CID 16357397.

- ^ a b Johnson, A. Michael (December 1990). "Speed of Mental Rotation as a Function of Problem-Solving Strategies". Perceptual and Motor Skills. 71 (3): 803–806. doi:10.2466/pms.1990.71.3.803. PMID 2293182. S2CID 34521929.

- ^ Jones, Bill; Anuza, Teresa (December 1982). "Effects of Sex, Handedness, Stimulus and Visual Field on 'Mental Rotation'". Cortex. 18 (4): 501–514. doi:10.1016/s0010-9452(82)80049-x. PMID 7166038. S2CID 4479407.

- ^ Hertzog, Christopher; Rypma, Bart (February 1991). "Age differences in components of mental-rotation task performance". Bulletin of the Psychonomic Society. 29 (2): 209–212. doi:10.3758/BF03335237.

- ^ Caissie, A. F.; Vigneau, F.; Bors, D. A. (2009). "What does the Mental Rotation Test Measure? An Analysis of Item Difficulty and Item Characteristics" (PDF). The Open Psychology Journal. 2 (1): 94–102. doi:10.2174/1874350100902010094.

- ^ Shepard, R. N., & Metzler, J., "Mental rotation: Effects of Dimensionality of Objects and Type of Task", Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, Vol 14, Feb 1988, pp. 3-11.

- ^ Shepard, R. N.; Metzler, J. (1971). "Mental Rotation of Three-Dimensional Objects" (PDF). Science. 171 (3972): 701–703. Bibcode:1971Sci...171..701S. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.610.4345. doi:10.1126/science.171.3972.701. JSTOR 1731476. PMID 5540314. S2CID 16357397.

- ^ Vandenberg, Steven (1978). "Mental Rotations, a Group Test of Three-Dimensional Spatial Visualization". Perceptual and Motor Skills. 47 (2): 599–604. doi:10.2466/pms.1978.47.2.599. PMID 724398. S2CID 32296116.

- ^ Peters, Michael (2005-03-01). "Sex differences and the factor of time in solving Vandenberg and Kuse mental rotation problems". Brain and Cognition. 57 (2): 176–184. doi:10.1016/j.bandc.2004.08.052. PMID 15708213. S2CID 24172762.

- ^ Harris, Irina M.; Egan, Gary F.; Sonkkila, Cynon; Tochon-Danguy, Henri J.; Paxinos, George; Watson, John D. G. (January 2000). "Selective right parietal lobe activation during mental rotation". Brain. 123 (1): 65–73. doi:10.1093/brain/123.1.65. PMID 10611121.

- ^ Prather, S.C; Sathian, K. (2002). "Mental rotation of tactile stimuli". Cognitive Brain Research. 14 (1): 91–98. doi:10.1016/S0926-6410(02)00063-0. PMID 12063132.

- ^ Gogos, Andrea; Gavrilescu, Maria; Davison, Sonia; Searle, Karissa; Adams, Jenny; Rossell, Susan L.; Bell, Robin; Davis, Susan R.; Egan, Gary F. (2010-01-01). "Greater superior than inferior parietal lobule activation with increasing rotation angle during mental rotation: An fMRI study". Neuropsychologia. 48 (2): 529–535. doi:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2009.10.013. PMID 19850055. S2CID 207235806.

- ^ Kawasaki, Tsubasa; Higuchi, Takahiro (3 July 2016). "Improvement of Postural Stability During Quiet Standing Obtained After Mental Rotation of Foot Stimuli". Journal of Motor Behavior. 48 (4): 357–364. doi:10.1080/00222895.2015.1100978. PMID 27162153. S2CID 205437812.

- ^ Habacha, Hamdi; Lejeune-Poutrain, Laure; Margas, Nicolas; Molinaro, Corinne (October 2014). "Effects of the axis of rotation and primordially solicited limb of high level athletes in a mental rotation task". Human Movement Science. 37: 58–68. doi:10.1016/j.humov.2014.06.002. PMID 25064695.

- ^ Jansen, Petra; Kellner, Jan (2015). "The role of rotational hand movements and general motor ability in children's mental rotation performance". Frontiers in Psychology. 6: 984. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00984. PMC 4503890. PMID 26236262.

- ^ Schmidt, Mirko; Egger, Fabienne; Kieliger, Mario; Rubeli, Benjamin; Schüler, Julia (2016). "Gymnasts and orienteers display better mental rotation performance than nonathletes" (PDF). Journal of Individual Differences. 37: 1–7. doi:10.1027/1614-0001/a000180.

- ^ a b Semrud-Clikeman, Margaret; Fine, Jodene Goldenring; Bledsoe, Jesse; Zhu, David C. (26 January 2012). "Gender Differences in Brain Activation on a Mental Rotation Task". International Journal of Neuroscience. 122 (10): 590–597. doi:10.3109/00207454.2012.693999. PMID 22651549. S2CID 20294308.

- ^ Quinn, Paul C.; Liben, Lynn S. (1 November 2008). "A Sex Difference in Mental Rotation in Young Infants". Psychological Science. 19 (11): 1067–1070. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.1013.7396. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02201.x. PMID 19076474. S2CID 7734508.

- ^ Nissan, Tali; Shapira, Oren; Liberman, Nira (October 2015). "Effects of Power on Mental Rotation and Emotion Recognition in Women". Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 41 (10): 1425–1437. doi:10.1177/0146167215598748. PMID 26231592. S2CID 23539538.

- ^ a b Zapf, Alexandra C.; Glindemann, Liv A.; Vogeley, Kai; Falter, Christine M. (17 April 2015). "Sex Differences in Mental Rotation and How They Add to the Understanding of Autism". PLOS ONE. 10 (4): e0124628. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1024628Z. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0124628. PMC 4401579. PMID 25884501.

- ^ Fisher, Maryanne L.; Meredith, Tami; Gray, Melissa (2017-09-07). "Sex Differences in Mental Rotation Are a Consequence of Procedure and Artificiality of Stimuli". Evolutionary Psychological Science. 4: 124–133. doi:10.1007/s40806-017-0120-x. S2CID 148788811. Retrieved 2020-07-10.

- ^ Meneghetti, Chiara; Cardillo, Ramona; Mammarella, Irene C.; Caviola, Sara; Borella, Erika (March 2017). "The role of practice and strategy in mental rotation training: transfer and maintenance effects". Psychological Research. 81 (2): 415–431. doi:10.1007/s00426-016-0749-2. PMID 26861758. S2CID 36170895.

- ^ Provost, Alexander; Johnson, Blake; Karayanidis, Frini; Brown, Scott D.; Heathcote, Andrew (September 2013). "Two Routes to Expertise in Mental Rotation". Cognitive Science. 37 (7): 1321–1342. doi:10.1111/cogs.12042. PMID 23676091.

- ^ Jansen, Petra; Quaiser-Pohl, Claudia; Neuburger, Sarah; Ruthsatz, Vera (June 2015). "Factors Influencing Mental-Rotation with Action-based Gender-Stereotyped Objects—The Role of Fine Motor Skills". Current Psychology. 34 (2): 466–476. doi:10.1007/s12144-014-9269-7. S2CID 143720932.

- ^ Richardson, John T. E. (1991-01-01). "Chapter 19 Gender differences in imagery, cognition, and memory". In Denis, Robert H. Logie and Michel (ed.). Advances in Psychology. Mental Images in Human Cognition. 80. North-Holland. pp. 271–303. doi:10.1016/s0166-4115(08)60519-1. ISBN 9780444888945.

- ^ Burnett, Sarah A. (1986). "Sex-related differences in spatial ability: Are they trivial?". American Psychologist. 41 (9): 1012–1014. doi:10.1037/0003-066x.41.9.1012.

- ^ Gardony, Aaron L.; Taylor, Holly A.; Brunyé, Tad T. (February 2014). "What Does Physical Rotation Reveal About Mental Rotation?". Psychological Science. 25 (2): 605–612. doi:10.1177/0956797613503174. PMID 24311475. S2CID 16285194.

References[]

- Amorim, Michel-Ange, Brice Isableu and Mohammed Jarraya (2006). "Embodied Spatial Transformations: "Body Analogy" for the Mental Rotation" (PDF). Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 135 (3): 327–347. doi:10.1037/0096-3445.135.3.327. PMID 16846268.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Cohen, M. (1996). "Changes in Cortical Activities During Mental Rotation: A mapping study using functional magnetic resonance imaging" (PDF). Brain. 119 (1): 89–100. doi:10.1093/brain/119.1.89. PMID 8624697. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 5, 2005. .

- Hertzog C., and Rypma B. (1991). "Age differences in components of mental rotation task performance". Bulletin of the Psychonomic Society. 29 (3): 209–212. doi:10.3758/BF03335237.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Johnson A.M. (1990). "Speed of mental rotation as a function of problem solving strategies". Perceptual and Motor Skills. 71 (3 pt. 1): 803–806. doi:10.2466/pms.1990.71.3.803. PMID 2293182. S2CID 34521929.

- Jones B., and Anuza T. (1982). "Effects of sex, handedness, stimulus and visual field on "mental rotation"". Cortex. 18 (4): 501–514. doi:10.1016/S0010-9452(82)80049-X. PMID 7166038. S2CID 4479407.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Lauer, J. E., Udelson, H. B., Jeon, S. O. and Lourenco, S. F. (2015). "An early sex difference in the relation between mental rotation and object preference". Frontiers in Psychology. 6: 558. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00558. PMC 4424807. PMID 26005426.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Moore, D. S. and Johnson, S. P. (2011). "Mental rotation of dynamic, three‐dimensional stimuli by 3‐month‐old infants". Infancy. 16 (4): 435–445. doi:10.1111/j.1532-7078.2010.00058.x. PMC 4547474. PMID 26312057.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Moreau, D., Mansy-Dannay, A., Clerc, J., & Guerrién, A. (2011). "Spatial ability and motor performance: Assessing mental rotation processes in elite and novice athletes". International Journal of Sport Psychology. 42 (6): 525–547.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Parsons, Lawrence M. (1987). "Imagined spatial transformations of one's hands and feet". Cognitive Psychology. 19 (2): 178–241. doi:10.1016/0010-0285(87)90011-9. PMID 3581757. S2CID 38603712.

- Pietsch, S., & Jansen, P. (2012). "Different mental rotation performance in students of music, sport and education". Learning and Individual Differences. 22 (1): 159–163. doi:10.1016/j.lindif.2011.11.012.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Quinn, P. C. and Liben, L. S. (2008). "A sex difference in mental rotation in young infants". Psychological Science. 19 (11): 1067–1070. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.1013.7396. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02201.x. PMID 19076474. S2CID 7734508.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Rohrer, T. (2006). "The Body in Space: Dimensions of embodiment" (PDF). Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) In Body, Language and Mind, vol. 2. Zlatev, Jordan; Ziemke, Tom; Frank, Roz; Dirven, René (eds.). Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, forthcoming 2006. - Shwarzer, G., Freitag, C. and Schum, N. (2013). "How crawling and manual object exploration are related to the mental rotation abilities of 9-month-old infants". Frontiers in Psychology. 4: 97. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00097. PMC 3586719. PMID 23459565.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Sekuler, R and Nash, D (1972). "Speed of size scaling in human vision". Psychonomic Science. 27 (2): 93–94. doi:10.3758/BF03328898.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Shepard, R and Cooper, L. "Mental images and their transformations." Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1982. ISBN 9780262192002.

- Sternberg, R.J. (2006). Cognitive Psychology 4th Edition. Belmont, CA: Thomson. ISBN 978-0534514211.

- Yule, Peter (1997). "A new spin on mental rotation". University of London. Archived from the original on February 10, 2009. Retrieved February 12, 2006. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)

External links[]

- Mental rotation lesson using PsyToolkit

- "Shepard-Metzler resource pack". An open source collection of items for use in the creation of mental rotation tasks.

- Cognitive science

- Cognitive tests

- Visual thinking

- Vision

- Space in life