Metropolitanate of Karlovci

Metropolitanate of Karlovci Карловачка митрополија Karlovačka mitropolija | |

|---|---|

Coat of Arms of Metropolitanate of Karlovci | |

| Location | |

| Territory | Habsburg Monarchy |

| Headquarters | Karlovci, Habsburg Monarchy (today Sremski Karlovci, Serbia) |

| Information | |

| Denomination | Eastern Orthodox |

| Sui iuris church | Self-governing Eastern Orthodox Metropolitanate |

| Established | 1708 |

| Dissolved | 1848 (1920) |

| Language | Church Slavonic Slavonic-Serbian |

The Metropolitanate of Karlovci (Serbian: Карловачка митрополија, romanized: Karlovačka mitropolija) was a de facto autocephalous (ecclesiastically independent) Eastern Orthodox Christian jurisdiction that existed between 1708 and 1848 (until 1920 as patriarchate) in the Habsburg monarchy comprising ethnic Serbs.[1] Between 1708 and 1713 it was known as the Metropolitanate of Krušedol, and between 1713 and 1848 as the Metropolitanate of Karlovci. In 1848, it was elevated to the Patriarchate of Karlovci, which existed until 1920, when it was merged with Metropolitanate of Belgrade and other Eastern Orthodox jurisdictions in the newly established Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes.

History[]

During the 16th and 17th centuries, all of the southern and central parts of the former medieval Kingdom of Hungary were under Turkish rule and organized as Ottoman Hungary. Since 1557, Serbian Orthodox Church in those regions was under jurisdiction of the Serbian Patriarchate of Peć. During the Austro-Turkish war (1683–1699), much of the central and southern Hungary was liberated and Serbian eparchies in those regions fell under the Habsburg rule. In 1689, Serbian Patriarch Arsenije III sided with Austrians, and moved from Peć to Belgrade in 1690, leading the Great Migration of the Serbs. In that time, a large number of Serbs migrated to southern and central parts of Hungary.[2][3]

Important privileges were given to them by Emperor Leopold I in three imperial chapters (Diploma Leopoldinum) the first issued on 21 August 1690, the second a year later, on 20 August 1691, and the third on 4 March 1695.[4] Privileges allowed Serbs to keep their Eastern Orthodox faith and church organization headed by archbishop and bishops. In next two centuries of its autonomous existence, autonomous Serbian Church in Habsburg Monarchy was organized on the basis of privileges originally received from the emperor.[5]

Creation and reorganization (1708–1748)[]

Until death in 1706, head of the church was Patriarch Arsenije III who reorganized eparchies and appointed new bishops. He held the title of Serbian Patriarch until the end of his life. New emperor Joseph I (1705-1711), following the advice of cardinal Leopold Karl von Kollonitsch abolished that title, and substitute it with less distinguished title of archbishop or metropolitan. In his decree, Emperor Joseph I stated, "we must make sure that they never elect another Patriarch since it is against the Catholic Church and the doctrine of the Fathers of the Church". According to that, future primates of the Serbian Orthodox Church in Habsburg Monarchy will bare the title of archbishop and metropolitan. The only exception from the Imperial decree was the case of later Serbian Patriarch Arsenije IV Jovanović (1725-1748) who brought his title directly from the historic see of Peć (1737).[6]

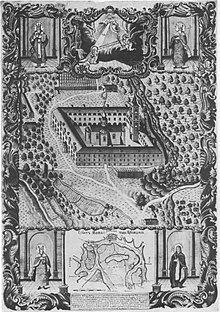

After the death of Patriarch Arsenije III (1706), the Serbian Church Council was held in the Monastery of Krušedol in 1708 and proclaimed Krušedol to be the official cathedral seat of the newly elected Archbishop and Metropolitan Isaija Đaković, while all administrative activities were moved to the nearby city of Sremski Karlovci. The monastery of Krušedol was bequest of the late medieval Serbian ruling family of Branković in the beginning of the 16th century, which was the main historical and national reason for the Serbs to choose this monastery as their Church capital.[7]

Between 1708 and 1713, the seat of the Metropolitanate was in the monastery of Krušedol, and in 1713 it was moved to Karlovci (today Sremski Karlovci, Serbia). The new archbishop (1713-1725) moved all administration from Krušedol to Karlovci.[8] So, the new capital of the Serbian Orthodox Church in Habsburg Monarchy became Sremski Karlovci which was confirmed by the seal of Imperial approval in the charter of Emperor Charles VI issued in October the same year.

During the Austro-Turkish War (1716-1718), regions of Lower Syrmia, Banat, central Serbia with Belgrade, and Oltenia were liberated from Ottoman rule, and under the Treaty of Passarowitz (1718) became part of Habsburg Monarchy.[9] Political change was followed by ecclesiastical reorganization. Eparchies in newly liberated regions were not subjected to the Metropolitan of Karlovci, mainly because Habsburg authorities did not want to allow the creation of unified and centralized administrative structure of the Eastern Orthodox Church in the Monarchy. Instead of that, they supported the creation of a separate metropolitanate for Eastern Orthodox Serbs and Romanians in liberated regions, centered in Belgrade. The newly created Metropolitanate of Belgrade was headed by metropolitan Mojsije Petrović (d. 1730). New autonomous Metropolitanate of Belgrade had jurisdiction over Kingdom of Serbia and Banat, and also over Oltenia.[10] The creation of new metropolitan province was approved by Serbian Patriarch Mojsije I Rajović (1712-1725), who also recommended future unification. Shortly after, two metropolitanates did merge, in 1726, and by the imperial decree of Charles VI, the administrative capital of Serbian Orthodox Church was moved from Sremski Karlovci to Belgrade in 1731. Metropolitan Vićentije Jovanović (1731-1737) resided in Belgrade.[6]

During the Austro-Turkish War (1737-1739), Serbian Patriarch Arsenije IV Jovanović (1725-1748) sided with the Habsburgs and in 1737 left Peć and came to Belgrade, taking over the administration of the Metropolitanate. He received imperial confirmation, and when Belgrade fell to Ottomans in the autumn of 1739, he moved the church headquarters to Sremski Karlovci.

Consolidation of the Metropolitanate (1748–1848)[]

In 1748, patriarch Arsenije IV died, and church council was held for the election of a new primate of the Serbian Orthodox Church in the Habsburg Monarchy. After the short tenure of metropolitan Isaija Antonović (1748-1749), another church council was held, electing the new metropolitan Pavle Nenadović (1749-1768).[11] During his tenure important administrative reforms were undertaken in the Metropolitanate of Karlovci. He also tried to help the patriarchal mother-church in Peć, under the Ottoman rule, but the old Serbian Patriarchate could not be saved. In 1766, the Serbian Patriarchate of Peć was finally abolished, and all of its eparchies that were under Turkish rule were overtaken by the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople. Serbian hierarchs of the Metropolitanate of Karlovci had no intention to submit themselves to the Greek Patriarch in Constantinople, and the Ecumenical Patriarchate also had enough wisdom not to demand their submission. From that time, Metropolitanate of Karlovci continued functioning as the fully independent ecclesiastical center of Eastern Orthodoxy in the Habsburg Monarchy, with seven suffragan bishops (Bačka, Vršac, Temišvar, Arad, Buda, Pakrac and Upper Karlovac).[12]

The position of Serbs and their Church in Habsburg Monarchy was further regulated by reforms brought about by Dowager-Empress Maria Theresa, Queen of Hungary (1740-1780). The Serbian Church Council of 1769 regulated various issues in a special act named "Regulament" and, later, in similar act called the Declaratory Rescript of the Illyrian Nation, published in 1779.[5] The death of Maria Theresa in 1780 marked the end the old imperial and royal House of Habsburg, highly respected among Orthodox Serbs, and succession passed to the new dynasty, called the House of Habsburg-Lorraine that ruled until 1918. Enlightened reforms of emperor Joseph II (1780-1790) affected all religious institutions in the Monarchy, including the Metropolitanate of Karlovci.

Serbian metropolitans of Sremski Karlovci promoted the Enlightenment by introducing western education in the schools established in Sremski Karlovci (1733), and in Novi Sad (1737). In order to counter the Roman Catholic influence, the school curricula was exposed to cultural influence of the Russian Orthodox Church. As early as in 1724 the Holy Synod of Russian Orthodox Church sent M. Suvorov to open a school in Sremski Karlovci, which graduates were thereof passed on to Kievan seminary, and the more gifted to the Academy in Kiev.[13] The Church liturgical language became Russian Slavonic, called the New Church Slavonic. On another hand, baroque influence became visible in the church architecture, iconography, literature and theology.[14]

During the eighteenth century the Metropolitanate maintained close connections with Kiev and the Russian Orthodox Church. Many Serbian theological students were educated in Kiev. A Seminary was open in 1794 which educated Orthodox priests during the nineteenth century for the needs of the Karlovci Metropolitanate and beyond.[5]

By the end of the 18th century, the Metropolitanate of Karlovci included a large territory that stretched from the Adriatic Sea to Bukovina and from Danube and Sava to Upper Hungary. During the long tenure of highly conservative metropolitan Stefan Stratimirović (1790-1836),[15] internal reforms were halted, resulting in the gradual formation of two fractions that would subsequently mark the life of Orthodox Serbs in the Metropolitanate, and later Patriarchate of Karlovci throughout the 19th century. First fraction was clerical and conservative. It was led by majority of bishops and higher clergy. Second fraction was oriented towards further reforms within the church administration, in order to allow more influence on decision making to lower clergy, laity and civil leaders. In the same time, aspirations towards Serbian national autonomy within the Empire gained great importance, leading to historical events of 1848.[16]

Revolution 1848/49[]

On the cultural and educational level, Serbs in the period 1790–1848 make great progress. The national revival that affected all the peoples of the Habsburg monarchy did not pass by the Serbs either. With monetary contributions from the Karlovci merchant Dimitrije Anastasijević Sabov. In 1791, the first modern high school for Serbs was founded - Karlovci High School. In order to raise the level of education of the priests in the Karlovci Metropolitanate, Stefan Stratimirović founded the Clerical High School of Karlovci in 1794. At the beginning of the 19th century, the High School of Novi Sad was opened. In 1812, a school for teachers was opened in Santandreja, which was transferred to Sombor in 1816 (today the Faculty of Teacher Education in Sombor). In Arad in 1815/16,a teacher's school was opened on the initiative of the Serbian benefactor Sava Tekelija. Тhe school will be attended by Serbs and Romanians. In 1826, Matica Srpska was founded with its headquarters in Pest. Newspapers and magazines in the Serbian language are launched (Serbskija novini, Slavenoserbskija vjedomosti, Novine serbske, Letopis, Backa vila, etc.). In 1842, the first Serbian reading room was founded in Irig.[17] At about the same time, the national revival of the Hungarians began. They founded cultural and educational institutions, started newspapers, opened reading rooms and schools.With the intention of creating an ethnically homogeneous and centralized Hungary, the vernacular is being pushed out of churches and schools, and Hungarian is being imposed. In 1820,[17] the Subotica Gymnasium was prescribed a textbook in the Hungarian language entitled "A brief overview of the basics of the grammar of the Hungarian language in five volumes for six grades." (lat. Epitome institutionum grammaticarum linguae hungaricae in quinque tomulis pro sex classibus).[17] In 1832, Bishop Stefan Stanković of Buda was ordered to expel the Slavo-Serbian language from his diocese. At the Hungarian Parliament, it was requested that church books be written in Hungarian. In 1847, the Hungarian palatine instructed Metropolitan Rajačić to correspond in Hungarian, not Latin.[17]

On the news that the revolution had begun in Vienna, on March 15, 1848, the Hungarian youth in Pest announced their national program, which was presented in 12 points. That program will also be accepted by the Hungarian Parliament, which sat in Požun. Emperor Ferdinand V confirmed the first Hungarian government accountable to the Hungarian Parliament on March 17.[18][19] Serbs from Pest gathered around the "Pantheon", "Tekelijanum" and Matica Srpska pointed out their national-political demands. Aiming to reach an agreement with the Hungarians, the program of the Serbs from Pest recognized the Hungarian people and the "diplomatic dignity of the Hungarian language in Hungary",with that the Serbs being recognized as a nation, to be guaranteed the free use of language in public affairs, free management of the church, inclusion of secular persons in consistories, free management of schools, funds and foundations, convening of the Church-People's Assembly every year and its right to direct address to the ruler, inclusion in the highest state authorities, rearrangement of the military border, a worthy place for metropolitan and bishop on the Diet, and the right to vote on the Diet for District of Potisje and Velika Kikinda. The act ends with the message: "Loyalty to the king, every sacrifice to the fatherland, brotherly love to the Hungarians!" [19]

The Hungarian side, however, did not accept the program of Serbs from Pest, although it did not provide for a separate area for Serbs.[20][19] Josif Rajačić and Jovan Hadžić, as representatives of the Serbian people, presented to the Hungarian government in Požuna, among other demands of a socio-economic nature, a request to be approved to convene a church-people's assembly in Karlovci. They demanded that a special Serbian office in charge of school and church matters be established within the Ministry of Education, the church be guaranteed uninterrupted work and that special courts and jurisdictions be formed. Their demands were not understood either and remained unfulfilled.[19] Unable to fight for their rights in this way, Serbs have reached an unenviable position. On one side stood the Hungarian government, relentless towards the non-Hungarian peoples, and on the other side stood the selfish Austrian court. Aware of that, on March 18, Metropolitan Rajačić tried to dissuade the people and the episcopate from hasty moves by means of a circular from Požun:

"Don't look at anyone! Reject any temptation, do not listen to any other teacher, because they will drag you into evil and temptation. Listen only to the voice of your archpastor and spiritual fathers who have never deceived you, never led you to evil." -Metropolitan Josif Rajačić

However, it was too late for such appeals. News of the events in Vienna and Pest reached Srem, Banat and Backa, causing spontaneous riots and movements among citizens and peasants. Of the larger Serb towns, Veliki Beckerek, Vršac, Pančevo, Zemun, Mitrovica, Novi Sad, and Vukovar were affected.[19]

At the Novi Sad Assembly held on March 27, it was demanded that Serbs from Dalmatia, Potisk and Velika Kikinda districts be represented at the annual church-people's assembly. reorganization of the Military Border, abolition of the feudal order, limitation of military jurisdiction to the period of active military service and the right of border guards to elect their officers.Out of prudence towards the Hungarian side, the request for direct traffic between the Church-People's Assembly and the ruler was omitted, instead of through the Hungarian government and the Hungarian ParliamentThat the Novi Sad Assembly was not directed against the Hungarian government is shown by the case of Stratimirović, who came to this gathering adorned with a Hungarian cockade.[21] The requests of the Novi Sad Assembly were forwarded to the Hungarian Parliament by a deputation headed by lawyer Aleksandar Kostić and a young resigned lieutenant and former law student Đordje Stratimirović (April 8–9).[19] Although Hungarian Finance Minister Lajos Kossuth was initially willing to promise Serbs religious equality, the use of the vernacular in the church and internal affairs, civil service on merit, the conflict with him came when Stratimirović openly demanded the implementation of the rights deriving from privileges and autonomy, which was in conflict with the then Hungarian revolutionary national policy: the unity of the country in every way.[22][19][23] The failure of the Novi Sad deputation resulted in further political manifestations, and in the end the convening of the Serbian National Assembly in Karlovci (for May 13, 1848).[24]

The Assembly was composed of authorized representatives of the Serbian people in Croatia, Slavonia, Bačka, Banat and the rest of Hungary, and it was attended by many guests from all over Serbia. Among them, Serbs from the Principality of Serbia stood out:Father Matija Nenadović, Dimitrije Matić, Konstantin Branković, , , etc.[25][26] In order to avoid legal problems, the assembly was constituted as a church-people's assembly.[27][24] The Assembly was opened by the Archbishop and Metropolitan of Karlovci Josif Rajačić at 9 am with a sermon, in which he "presented all the history and destiny of the Serbian people and called on the gathered people to take care of their future and independence according to their rights." Then the protosyncellus (later Bishop of Gornji Karlovci) came on the scene with his speech "on the rights and privileges of the people", in which he stated "how the Serbian people under the treaties, which he concluded with the Austrian emperors when he moved to Hungary,he has the right, to govern himself independently, to elect a duke, as a world leader, and a patriarch, as a spiritual leader. " At that, the people unanimously proclaimed Metropolitan Rajačić the patriarch of Serbia, and elected the imperial-royal colonel Stevan Šupljikac as the duke of Serbia.[25][28] Observed from the church-canonical point of view, this elevation of Metropolitan Rajačić to the Serbian patriarch was illegal. However, in the atmosphere of general national enthusiasm, no special attention was paid to this fact.

Aware that for the development of their national being it is necessary to break the chains "which in their naturally imposed duty of advancement and improvement bother them", the Serbian people declared themselves "politically free and independent under the Austrian home and the general Hungarian crown".[27] Referring to the rights arising from the agreements concluded "with the Austrian House and the Hungarian Crown", the Serbian people expressed their desire to declare Serbian Vojvodina, in the scope of "Srem with the border, Baranja, Backa with the Becej District and Shajkaski Battalion, and Banat with the border and district of Kikinda. "[29][27][30] In order to persuade the Austrian emperor to accept the conclusions of the assembly, a delegation led by Patriarch Rajačić was sent to him. On the way to Innsbruck, where the imperial family took refuge from the riots in Vienna, Rajačić arrived in Zagreb, where he enthroned the Illyrian-minded General Josip Jelačić as Croatian ban.[31]

On June 19, Austrian Emperor Ferdinand refused to confirm the decisions of the May Assembly that Rajačić presented to him in a private audience, explaining it with the words: "I cannot approve the decisions of the illegal assembly, made by some of my Greek-ununited subjects together with foreigners from Serbia. I am ready to fulfill all the frequent demands of my Greek-non-united subjects submitted in a lawful manner, but only the Hungarian National Assembly, the Hungarian Ministry and your lawful (ie church) people's assembly are the bodies through which you can express your wish to me."[32][33] In other words, the Austrian emperor left the Serbs at the mercy of the Hungarian government.[34] While official court circles were very reserved towards Serbian demands (probably also because of Pal Esterhazy, a representative of the Hungarian government, who attended a private audience), the court chamberlains and members of the dynasty welcomed them with understanding. The mother of the future emperor Franz Joseph, Archduchess Sophia, made it known that she sympathized with the Serbs, weaving a ribbon with a Serbian tricolor, and Archduke Franz Carlo supported the Serbs and encouraged them in their aspirations.[35]

The Hungarian government responded threateningly to the decisions of the May Assembly. On June 3, Minister of Religion and Education Jozef Etves tried, under threat of retaliation, to force Rajačić to hold a church council scheduled for him in Timisoara and to publicly commit to receiving every imperial order through the government in Pest in the future.[34][36] At the Hungarian Parliament in Pest on July 11, 1848, Kossuth announced that he would stifle the Serbian movement at the first opportunity, that is, when he mobilized the army. Once again in their history, Serbs had to go through difficult struggles and pogroms, this time without anyone's support from the side. Busy with fighting in Italy and trouble at home in Vienna, the Austrian court remained passive towards Hungary until the end of the year, while nothing concrete was done on the Croatian side against the Hungarians until the end of September. Along with the difficult battles against the Hungarians, there was a conflict over the leadership in the movement between the patriarch and the "supreme leader", the young and impulsive George Stratimirović. In the absence of Duke Šupljikac, Stratimirović practically functioned as a secular leader, which did not impress the patriarch and some border officers. Along with the difficult battles against the Hungarians, there was a conflict over the leadership in the movement between the patriarch and the "supreme leader", the young and impulsive George Stratimirović. In the absence of Duke Šupljikac, Stratimirović practically functioned as a secular leader, which did not impress the patriarch and some border officers.[37] In this political struggle, the patriarch triumphed, while Stratimirović was compromised and thrown into the shadows.

When Franz Joseph came to the throne after the overthrow of the weak-minded Ferdinand, he confirmed with a patent of December 15, 1848, the decisions of the May Assembly on the election of the patriarch and duke: In recognition of these merits and as a special proof of our imperial mercy and care for the survival and well-being of the Serbian people, we decided to appoint you the supreme ecclesiastical dignity - patriarchal, as it existed in earlier times and was associated with the archbishopric in Karlovci, and to award the title and dignity of patriarch to our beloved and faithful Archbishop of Karlovci, Josif Rajačić."[38][39] On March 4, 1849, the Authorized Constitution of the Habsburg Monarchy (the so-called March Constitution) was adopted in Olomouc. Article 72 of the constitution guaranteed Serbs within the voivodship such institutions "as are based on older charters and imperial declarations from recent times for the preservation of their church community." The enacted constitution also surprised the patriarch, who was traditionally loyal to the court. Article 72 of the Authorized Constitution, as well as the partial recognition of the request of the May Assembly by the patent of December 15, 1848, did not resolve the issue of rearranging the church situation among Orthodox believers. In order to succeed in this matter, the new government of Vienna invited Rajačić to Vienna, after dismissing him from the duties of the imperial commissioner for counties inhabited by Serbs, in order to consult with him regarding church issues. The patriarch then agreed with Bach to convene a gathering of Orthodox bishops, similar to Catholics and evangelicals, in order to resolve burning issues. In that way, at the beginning of October 1849, the Minister of the Interior could propose to his fellow ministers to invite all nine Orthodox bishops to Vienna for that purpose. The Council of Ministers and the ruler agreed in principle to this idea. However, it took a year to realize this idea.[40]

The Serbs left the Revolution of 1848 with an autonomous status, and on November 18, 1849, they received confirmation from the court about the established Voivodeship of Serbia and Banat of Temeschwar. The title of duke went to the Austrian emperor, and the archduke to Mayerhofer. The duchy was directly subordinated to Vienna. The Military Border was excluded from the territory of the Duchy. When the Duchy was founded, all functions of the Main Board and its president Rajačić ceased.

Hungarians, Germans and Bunjevci, led by Karl Latinović, spoke out against the creation of the Duchy in Bačka. Presenting this movement to the authorities as separatist, Patriarch Rajačić demanded that the ringleaders be tried as traitors, and that the Duchy be organized as soon as possible (October 31, 1849).[40]

Eparchies under direct or spiritual jurisdiction of Karlovci[]

It included following eparchies:

| Eparchy | Seat | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Eparchy of Arad | Arad | |

| Eparchy of Bačka | Novi Sad | Bačka |

| Eparchy of Belgrade | Belgrade (Beograd) | (1726–1739) |

| Eparchy of Buda | Szentendre (Sentandreja) | |

| Eparchy of Gornji Karlovac | Karlovac | |

| Kostajnica | (1713–1771) | |

| Lepavina | (1733–1750) | |

| Mohács (Mohač) | (until 1732) | |

| Eparchy of Pakrac | Pakrac | Now Eparchy of Slavonia |

| Râmnicu Vâlcea (Rimnik) | (1726–1739) | |

| Eparchy of Srem | Sremski Karlovci | Syrmia |

| Timișoara (Temišvar) | Banat | |

| Eparchy of Valjevo | Valjevo | (1726–1739) |

| Eparchy of Vršac | Vršac | Banat |

| Sibiu (Sibinj) | Spiritual jurisdiction only | |

| Chernivtsi (Černovci) | Spiritual jurisdiction only | |

| Eparchy of Dalmatia | Šibenik | Spiritual jurisdiction only |

Heads of Serbian Orthodox Church in Habsburg Monarchy, 1690–1848[]

| No. | Primate | Portrait | Personal name | Reign | Title | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Arsenije III Арсеније III Arsenius III |

|

Arsenije Čarnojević Арсеније Чарнојевић |

1690–1706 | Archbishop of Peć and Serbian Patriarch | Leader of the First Serbian Migration |

| 2 | Isaija I Исаија I Isaias I |

|

Isaija Đaković Исаија Ђаковић |

1708 | Metropolitan of Krušedol | |

| 3 | Sofronije Софроније Sophronius |

|

Sofronije Podgoričanin Софроније Подгоричанин |

1710–1711 | Metropolitan of Krušedol | |

| 4 | Vikentije I Викентије I Vicentius I |

|

Vikentije Popović-Hadžilavić Викентије Поповић-Хаџилавић |

1713–1725 | Metropolitan of Karlovci | |

| 5 | Mojsije I Мојсије I Moses I |

|

Mojsije Petrović Мојсије Петровић |

1726–1730 | Metropolitan of Belgrade and Karlovci | |

| 6 | Vikentije II Викентије II Vicentius II |

|

Vikentije Jovanović Викентије Јовановић |

1731–1737 | Metropolitan of Belgrade and Karlovci | |

| 7 | Arsenije IV Арсеније IV Arsenius IV |

|

Arsenije IV Jovanović Šakabenta Арсеније Јовановић Шакабента |

1737–1748 | Archbishop of Peć and Serbian Patriarch | Leader of the Second Serbian Migration |

| 8 | Isaija II Исаија II Isaias II |

|

Isaija Antonović Јован Антоновић |

1748–1749 | Metropolitan of Karlovci | |

| 9 | Pavle Павле Paul |

|

Pavle Nenadović Павле Ненадовић |

1749–1768 | Metropolitan of Karlovci | |

| 10 | Jovan Јован John |

|

Jovan Georgijević Јован Ђорђевић |

1768–1773 | Metropolitan of Karlovci | |

| 11 | Vićentije III Вићентије III Vicentius III |

|

Vićentije Jovanović Vidak Вићентије Јовановић Видак |

1774–1780 | Metropolitan of Karlovci | |

| 12 | Mojsije II Мојсије II Moses II |

|

Mojsije Putnik Мојсије Путник |

1781–1790 | Metropolitan of Karlovci | |

| 13 | Stefan I Стефан I Stephen I |

|

Stefan Stratimirović Стефан Стратимировић |

1790–1836 | Metropolitan of Karlovci | |

| 14 | Stefan II Стефан II Stephen II |

|

Stefan Stanković Стефан Станковић |

1836–1841 | Metropolitan of Karlovci | |

| 15 | Josif Јосиф Joseph |

|

Josif Rajačić Јосиф Рајачић |

1842–1848 | Metropolitan of Karlovci | Elevated to Patriarch |

See also[]

- Patriarchate of Karlovci

- Serbian Orthodox Church

- List of heads of the Serbian Orthodox Church

- Religion in Serbia

- Religion in Vojvodina

References[]

- ^ The Encyclopedia of Eastern Orthodox Christianity, Volume 2 by John Anthony McGuckin, Wiley, Feb 8, 2011 page 564

"The Serbian Church organization in the Habsburg monarchy was centered on the metropolitan of (Sremski) Karlovac, which in 1710 the patriarch of Peć, Kalinik I, recognized as autonomous." - ^ Pavlović 2002, pp. 19–20.

- ^ Ćirković 2004, p. 144, 244.

- ^ Plamen Mitev (editor): Empires and Peninsulas: Southeastern Europe Between Karlowitz and the Peace of Adrianople, 1699 - 1829, LIT Verlag Münster, 2010 page 257

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Mario Katic, Tomislav Klarin, Mike McDonald: Pilgrimage and Sacred Places in Southeast Europe: History, Religious Tourism and Contemporary Trends, LIT Verlag Münster, Oct 1, 2014 page 207

- ^ Jump up to: a b Jelena Todorovic: An Orthodox Festival Book in the Habsburg Empire: Zaharija Orfelin's Festive Greeting to Mojsej Putnik (1757), Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2006 pages 12-13

- ^ Ćirković 2004, p. 150.

- ^ Ćirković 2004, p. 150-151.

- ^ Ingrao, Samardžić & Pešalj 2011.

- ^ Ćirković 2004, p. 151-152.

- ^ Ćirković 2004, p. 165.

- ^ Bojan Aleksov: Religious Dissent Between the Modern and the National: Nazarenes in Hungary and Serbia 1850-1914, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, 2006 page 33

- ^ Aidan Nichols: Theology in the Russian Diaspora: Church, Fathers, Eucharist in Nikolai Afanasʹev (1893-1966), CUP Archive, 1989 page 49

- ^ Augustine Casiday: The Orthodox Christian World, Routledge, Aug 21, 2012 page 135

- ^ Ćirković 2004, p. 167, 171.

- ^ Ćirković 2004, p. 200-202.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Васин 1981, стр. 311–312.

- ^ Rokai Peter; Đere Zoltan; Pal Tibor; Kasaš Aleksandar (2002). Istorija Mađara https://books.google.rs/books?id=I8snAQAACAAJ&redir_esc=y. Beograd: Clio. pp. 430–33. External link in

|title=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g Гавриловић Славко (1981), Срби у Хабсбуршкој монархији од краја XVIII до средине XIX века (1981). Историја српског народа. Београд: Српска књижевна задруга. pp. 5–106.

- ^ Микавица, Дејан 2011. Српско питање на Угарском сабору 1690-1918. Нови Сад: Филозофски факултет. pp. 69–70.

- ^ Györe, Zoltán (2009). Mađarski i srpski nacionalni preporod. Novi Sad: Vojvođanska akademija nauka i umetnosti. p. 449. ISBN 9788685889301.

- ^ Gavrilovic Slavko (1994). Срби у Хабсбуршкој монархији: 1792-1849. Novi Sad: Matica Srpska. pp. 51–52. ISBN 9788636302859.

- ^ Рокаи, Петер; Ђере, Золтан; Пал, Тибор; Касаш, Александар (2002). (2002). Istorija Mađara. Beograd: Clio. pp. 436–37. ISBN 9788671020350.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kletečka, Thomas; Schmied-Kowarzik, Anatol . (2005). Die Protokolle des Österreichischen Ministerrates 1848-1867. Wien. pp. xxvii.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ Jump up to: a b Павловић, Драгољуб М. (2009). Србија и српски покрет у Јужној Угарској 1848. и 1849. Београд. p. 16.

- ^ Гавриловић, Славко (1994). (1994). Срби у Хабсбуршкој монархији (1792-1849). Нови Сад: Матица српска. pp. 37–47. ISBN 9788636302859.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Микавица, Дејан; Гавриловић, Владан; Васин, Горан (2007). (2007). Знаменита документа за историју српског народа 1538-1918. Нови Сад: Филозофски факултет. ISBN 9788680271750.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ "Рођена браћо српска у Срему, Бачкој и Банату!" Српске новине, бр. 34 (1848); "Вести са народне скупштине у Карловци", Српске новине, бр. 36 (1848); "Вести са народне скупштине у Карловци", Српске новине, бр. 37 (1848)

- ^ Кркљуш, Љубомирка (1997)., "Светозар Милетић и мисао о аутономији Срба у Јужној Угарској". (1997). Актуелност мисли Светозара Милетића о ослобођењу и уједињењу српског народа. Београд: Завод за уџбенике и наставна средства. стр. pp. 95–111. ISBN 9788617053701.

- ^ Микавица, Дејан (2007). Михаило Полит Десанчић:Вођа српских либерала у Аустроугарској. Нови Сад: Филозофски факултет. p. 30.

- ^ Микавица, Дејан (2010). "Равноправност и дискриминација на угарској Диети 1690-1848". Истраживања: Филозофски факултет у Новом Саду. pp. 213–261.

- ^ Springer, Anton (1865). Geschichte Oesterreichs seit dem Wiener Frieden 1809. Leipzig. p. 446.

- ^ Павловић, Драгољуб М. (2009). Србија и српски покрет у Јужној Угарској 1848. и 1849. . Београд. p. 22.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Васин, Горан (2010). "Национално-политичка борба Срба у Угарској 1848-1884". Истраживања: Филозофски факултет у Новом Саду. pp. 21: 311–336.

- ^ Микавица, Дејан (2010). "Равноправност и дискриминација на угарској Диети 1690-1848". Истраживања: Филозофски факултет у Новом Саду. pp. 21: 213–261.

- ^ Микавица, Дејан (2011). Српско питање на Угарском сабору 1690-1918. Нови Сад: Филозофски факултет. p. 82.

- ^ Васин, Горан (2010). "Национално-политичка борба Срба у Угарској 1848-1884". Истраживања: Филозофски факултет у Новом Саду. pp. 21: 311–336.

- ^ Гавриловић, Славко (1994) (1994). .Срби у Хабсбур шкој монархији (1792-1849). Нови Сад: Матица српска. pp. 125–26. ISBN 9788636302859.

- ^ Микавица, Дејан (2015) (2015). Српска политика у Хрватској и Славонији 1538-1918. Нови Сад: Филозофски факултет. p. 98. ISBN 9788660653347.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Никић, Федор (1981). Радови (1919—1929). 1. Београд. pp. 105–106.CS1 maint: location (link)

Sources[]

- Ćirković, Sima (2004). The Serbs. Malden: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 9781405142915.

- Đorđević, Miloš Z. (2010). "A Background to Serbian Culture and Education in the First Half of the 18th Century according to Serbian Historiographical Sources". Empires and Peninsulas: Southeastern Europe between Karlowitz and the Peace of Adrianople, 1699–1829. Berlin: LIT Verlag. pp. 125–131. ISBN 9783643106117.

- Fotić, Aleksandar (2008). "Serbian Orthodox Church". Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire. New York: Infobase Publishing. pp. 519–520. ISBN 9781438110257.

- Гавриловић, Славко (2006). "Исаија Ђаковић: Архимандрит гргетешки, епископ јенопољски и митрополит крушедолски" (PDF). Зборник Матице српске за историју. 74: 7–35.

- Грујић, Радослав (1929). "Проблеми историје Карловачке митрополије". Гласник Историског друштва у Новом Саду. 2: 53–65, 194–204, 365–379.

- Грујић, Радослав (1931). "Пећки патријарси и карловачки митрополити у 18 веку". Гласник Историског друштва у Новом Саду. 4: 13–34, 224–240.

- Ingrao, Charles; Samardžić, Nikola; Pešalj, Jovan, eds. (2011). The Peace of Passarowitz, 1718. West Lafayette: Purdue University Press. ISBN 9781557535948.

- Пузовић, Предраг (2014). "Рад митрополита Павла Ненадовића на просвећивању свештенства и народа". Три века Карловачке митрополије 1713-2013 (PDF). Сремски Карловци-Нови Сад: Епархија сремска, Филозофски факултет. pp. 166–177.

- Пузовић, Предраг (2014). "Рад митрополита Павла Ненадовића на завођењу монашке дисциплине у фрушкогорским манастирима" (PDF). Богословље: Часопис Православног богословског факултета у Београду. 73 (1): 120–125.

- Radić, Radmila (2007). "Serbian Christianity". The Blackwell Companion to Eastern Christianity. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing. pp. 231–248. ISBN 9780470766392.

- Точанац, Исидора Б. (2007). "Београдска и Карловачка митрополија: Процес уједињења (1722-1731)" (PDF). Историјски часопис. 55: 201–217. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-03-24. Retrieved 2019-05-05.

- Точанац, Исидора Б. (2008). Српски народно-црквени сабори (1718-1735). Београд: Историјски институт САНУ. ISBN 9788677430689.

- Точанац-Радовић, Исидора Б. (2014). Реформа Српске православне цркве у Хабзбуршкој монархији за време владавине Марије Терезије и Јосифа II (1740-1790). Београд: Филозофски факултет.

- Точанац-Радовић, Исидора Б. (2014). "Настанак и развој институције Српског народно-црквеног сабора у Карловачкој митрополији у 18. веку (The appearance and the development of the institution of Serbian national-clerical council in the Metropolitanate of Karlovci in 18th century)". Три века Карловачке митрополије 1713-2013 (PDF). Сремски Карловци-Нови Сад: Епархија сремска, Филозофски факултет. pp. 127–144.

- Точанац-Радовић, Исидора Б. (2015). "Српски календар верских празника и Терезијанска реформа" (PDF). Зборник Матице српске за историју. 91: 7–38.

- Todorović, Jelena (2006). An Orthodox Festival Book in the Habsburg Empire: Zaharija Orfelin's Festive Greeting to Mojsej Putnik (1757). Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 9780754656111.

- Вуковић, Сава (1996). Српски јерарси од деветог до двадесетог века (Serbian Hierarchs from the 9th to the 20th Century). Евро, Унирекс, Каленић.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Metropolitanate and Patriarchate of Karlovci. |

- About Metropolitanate of Karlovci (in Serbian)

- Vojvodina under Habsburg rule

- Serbian Vojvodina

- History of Syrmia

- Habsburg Serbs

- Defunct religious sees of the Serbian Orthodox Church

- 1691 establishments in the Habsburg Monarchy

- 1848 disestablishments in the Austrian Empire

- History of the Serbian Orthodox Church